Opinion: For indie devs, game design and marketing are the same thing

This post was originally written on the Ooblets Patreon as advice for indie devs, and was reprinted here with permission from author Ben Wasser. Wasser is working on the design and marketing of farming/life/silly dancing sim Ooblets with Rebecca Cordingley.

In an interview Rebecca and I did with PC Gamer last year, I mentioned offhand that we used a “marketing first” approach to making Ooblets. Since that article ran, I’ve had a bunch of people who’ve been following the game’s development bring that phrase up to me, so I figured I’d write out what I meant by it in some more detail.

Disclaimer:

I’m not an expert and I don’t want to try to come across as one. I can just describe what’s been working for us on Ooblets and what I see working and not working for other people.

The wonderful thing about games is that they don’t need to fit a common convention, so I’m sure there are many that have and could succeed with drastically different strategies. This is just an outline of our strategy in the hopes that sharing it might be helpful to some people who are in similar circumstances to us.

Now that I’ve said all that, I’m going to jump right in with a bunch of claims asserted as facts! Forgive me!

The difference between gamedev and marketing

I won’t bury the lede here: There is no difference.

The biggest gaming news, reviews and hardware deals

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

Most of the gamedevs I’ve spoken to seem to see marketing as this secondary element of releasing a game, like QA or localization. They’ll ask questions like "when is a good time to start marketing our game?" To me, what they’re describing is "sales," not marketing.

If you’ve got a finished or nearly-finished product and are trying to convince people to buy it, you’re stuck in the unenviable position of a salesman. With sales, at the end of the day, your success is going to be bracketed by how appealing the product is, in ways you can’t really influence anymore.

Marketing is considering what’s appealing, integrating that into your product, and demonstrating that appeal.

Compared to something like a phone, where you have a functional baseline and can differentiate on other elements of appeal (materials, UI, etc.), a game is 100% about appeal. There’s no functional element of it. From the game mechanics to the art to the UI, it’s all about what will strike someone’s fancy. Your role in making a game is that of a marketer, whether you know it or not. Your game design, aesthetic, name, and every element of your process should be designed to appeal to people, and it needs to be from day one.

Game design and audience

Making your game appealing isn’t about selling out. There is no overarching general audience you can appeal to or find a common denominator with, but rather just a bunch of different audiences of different sizes.

Your gameplay mechanics and positioning are going to be a major part of what appeals to people, so marketing should be your first stop when formulating the very first ideas of your game.

The first few questions you need to answer before or while designing your game are "Who is your audience," "Does that audience actually exist (or exist enough to make this endeavor financially viable)," and "What does that audience like in a game?"

Whatever audience you choose to make a game for, keep them in the forefront of your decision-making processes.

If you want to make a deep, artsy game, you should consider the audience of people who like that sort of thing and make choices with their interests in mind. Maybe micro-transaction loot crates aren’t appropriate for that audience…

For example, one game design concept we try to follow in Ooblets is to always be nice to the player. You can see this when your ooblets learn a new move; You don’t have to pick an existing move to overwrite and permanently lose, because that wouldn’t be nice for the player. We feel this philosophy appeals to our specific audience but wouldn’t necessarily work if our audience was more like that of Super Meat Boy.

Hooks and high concept

I talk a lot about hooks as discrete draws that will grab people’s interest. It’s basically another way of saying appeal, but in less broad terms. You should be thinking about what hooks your game has, and make sure it’s got at least one.

You may have also heard of the term "high concept," which is about being able to sell your idea on the pitch alone, and not so much its execution. This can definitely be valuable for making your game appealing, but it’s not the only way to have hooks. A hook can be your aesthetics, humor, subject matter, gameplay—all of which are directly related to execution. That said, don’t rely on "good" execution as a hook; If you made the best-executed early-access multiplayer zombie survival game and released it in 2020, you’re still going to have a hard time selling it amongst the hundreds of other games that have saturated that market.

Here are a few examples of hooks in games:

— Minecraft - The main hook is that you have a level of interaction and control over a complex and open world environment that was pretty unheard of in gaming before it.

— Flappy Bird - The hook was a very lucky (or possibly genius?) mixture of high difficulty, small units of measuring success, and bringing it all together by making it easy to compare your score publicly on social media.

— PUBG - The hook is the Battle Royale concept which has become more recognizable to people through various media over the years, but hasn’t been fleshed out as extensively before in game format.

— Gang Beasts - The hook is that a variety of naturally-emerging funny and strange situations can play out in a social setting.

— Ooblets - Ooblets is definitely high concept in that it mixes two well-known gameplay mechanics that people already like and can imagine working well together, but we also try to leverage our aesthetics, tone, personality, and content to have as many small hooks as we can.

Differentiation

If I were writing this ten years ago, I’d put more of a focus on how well you execute your ideas, but with the extreme amount of competition in the gaming industry these days, I’d put way more of an emphasis on differentiating your ideas. It’s a struggle for mindshare, and if you have no momentum, you need to grab attention as quickly and simply as possible.

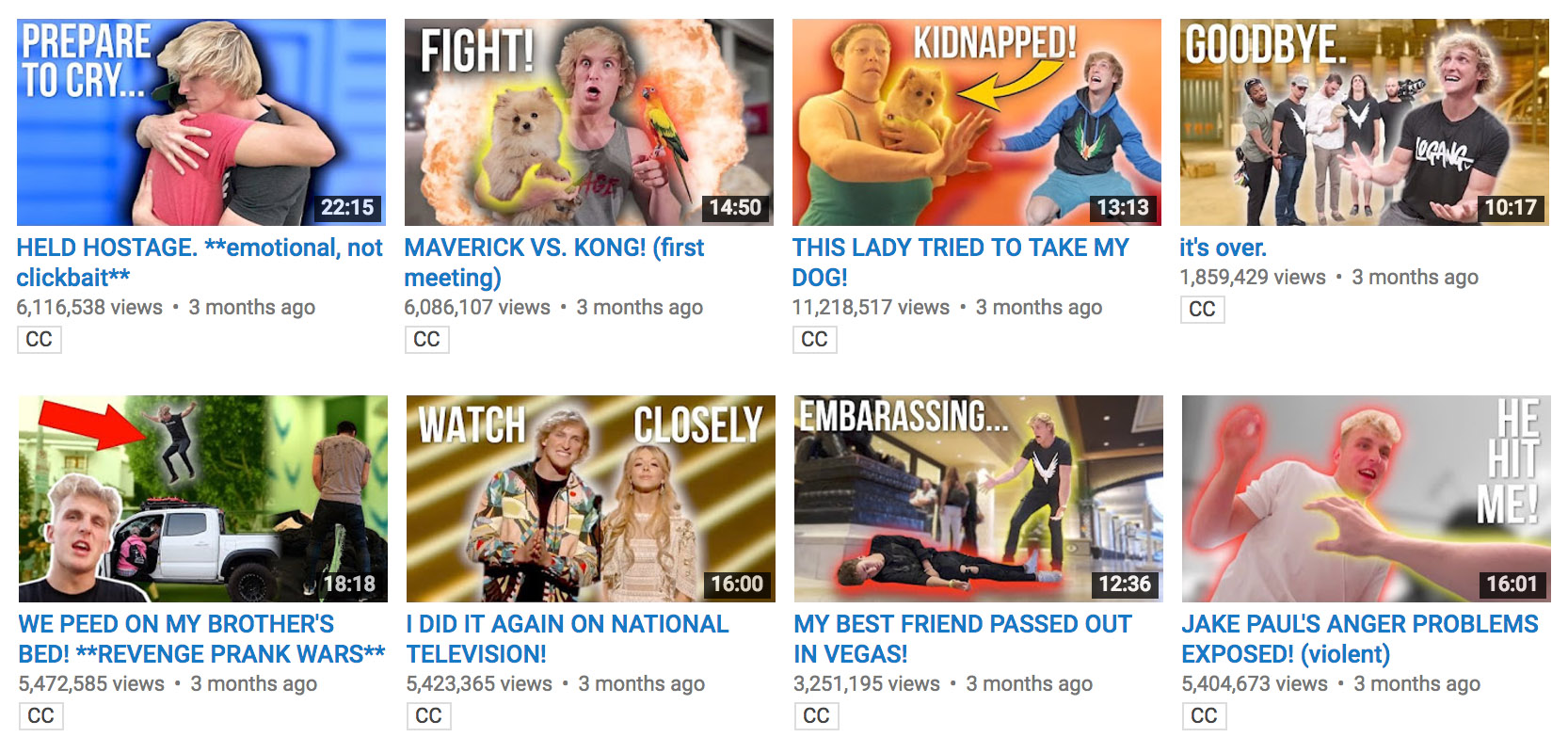

Youtube, especially looking at the top channels, is a great place to investigate this, as the concept has been distilled to an art over there. Using only thumbnails and titles, attention is clawed from the other millions of videos through techniques demonstrated below:

You don't necessarily need to emulate these precisely...

Think of what will make a vlogger want to cover your game. Think of what headline about your game the press could write that would get them clicks. Consider someone rapidly going through their Steam queue and what it would take to make them pause on your game.

Visuals

It should be obvious by now that there isn’t a scale of "graphics quality" like there was in years past where everyone was rushing to make computers simulate reality better than the competition. As that competition has sort of evened out, there’s been a shift back to mechanics and aesthetics, sort of like the shift from realism to impressionism in art. This is great for you, because you don’t need to compete on graphical fidelity with AAA games, but you’ll still need to compete for visual attention.

From Sacramento

Remember that the art in your game is Art with a capital A. Art is about emotion, grabbing interest, asking questions, and being creative. Leverage these attributes and think of what will make your game attractive or stand out compared to every other game.

Naming

People have a lot of difficulty with this one. We had a lot of difficulty with this one. What do you call your game?

Here’s a tip: AAA games have it a lot easier than you. They can call their games one-word generic titles like Battlefield and Destiny. They can pick long winding names like "Tom Clancy's Rainbow Six Siege" and "Warhammer 40,000: Inquisitor - Martyr." You might not want to try to emulate them if you don’t have their resources.

My general suggestion for indies would be to pick something either very clear and descriptive, something short and memorable, or something that will stand out and make people look twice.

Testing and realistic estimation

The worst case scenario is that you spend years of your life dedicated to a game that you’ve invested everything in and expect to do amazingly well… and it flops. Let's try to avoid that.

Data is what separates good marketing from simply trusting your judgment about what you think people will like.

You can inform your decisions through research, testing, and estimations— starting with the overall marketability of your game concept.

In the startup world, there’s a strategy to test out the viability of ideas by creating a landing page with a signup form before you ever start to build your product. If you can’t get traction on that, you don’t need to invest the time and money to ever build the product.

In game development, we have a bunch of ways to test ideas:

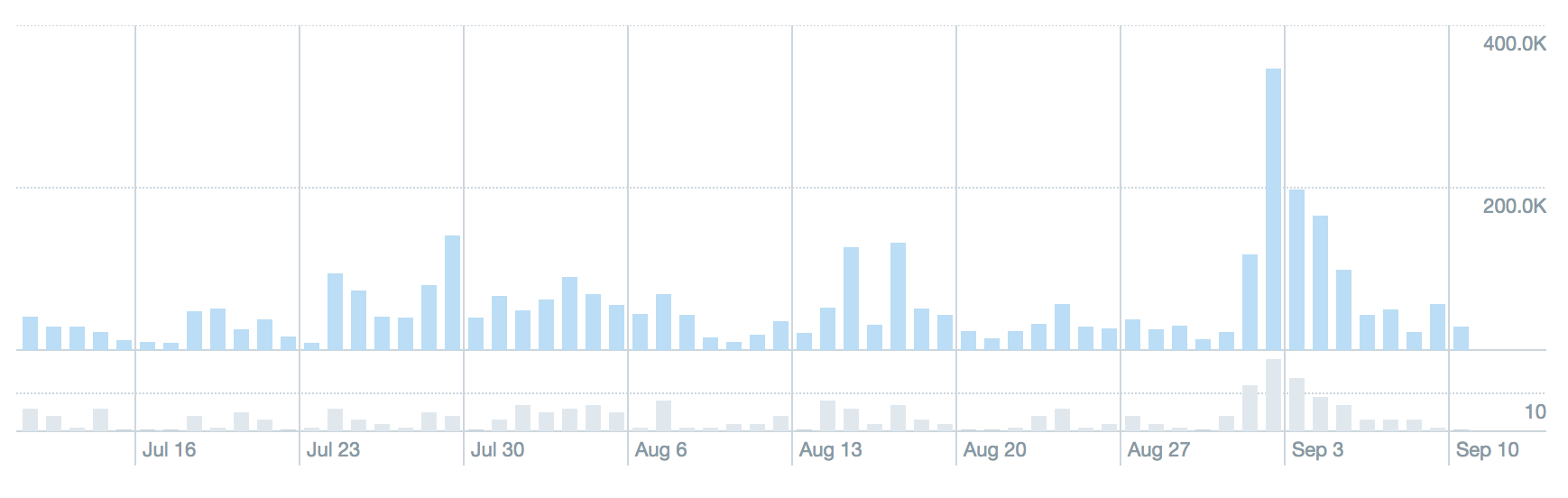

— Social media - Share early and often. If nobody is interested on social media and you’re not growing your audience, you need to switch gears and rethink things. On smaller scale items, like particular mechanics, aesthetics, or content, you can use social media performance to figure out what people like and what direction your game should take.

— Kickstarter - I’d definitely not jump into a Kickstarter without a lot of marketing ahead of time, but if you don’t take marketing seriously, it might be a valuable kick in the butt to see how well the if-you-build-it-they-will-come strategy could work for you by jumping straight into the deep end.

— Publishers - Your friends and family won’t be able to help you estimate whether real people will spend their money on your game. Publishers, on the other hand, have to wager a lot of money on your success, so if your game is in front of them and they’re all not interested, that’s very important data you can’t ignore.

Besides these big data points, I’d suggest you have a firm grasp on the market you’re entering, simply through being aware and open to the environment. The mistake I see a lot of devs making is comparing their game to games that came out in 2013. It might not seem like that long ago, and you may have started work on your game back then, but the reality is that the market has changed a lot.

The tools are better, there are more folks in the industry, and as such, there are way more games being released every year. What could stand out in 2013 won’t necessarily stand out today. To get a better idea, look at the recent releases for your genre on Steam. Look at their dates. Look at their number of reviews. It’s tough out there, and you shouldn’t be deceiving yourself. The more realistic you can be, the more rational your decisions will be.

Sharing and building an audience early

You probably know that we started sharing our work on Ooblets from the very first art test we ever did for it, but I’m not actually going to tell you that this is the absolute best strategy. I don’t know. I think it’s very possible to announce everything the same day you release your game and have it take off. For us, though, we couldn’t take that bet. We couldn’t spend the years of our life on something without any strong indications that it would be worthwhile in the end.

We also didn’t have a marketing budget or any connections in the industry, so sharing our development was the only asset we had to build an audience around. If a game is in a similar situation but has finished development, what assets do you have left to build an audience?

You can pray that power brokers somehow discover your game and like it enough to help you market it, but the reality of the situation is that Youtubers, streamers, and press prefer to follow interest, not generate it. If a portion of their (potential) audience are interested in a game, they’re going to be way more likely to try to capitalize on that interest than try to market a game nobody is interested in. It’s a feedback loop: If people are interested in something, the media will cover it and then more people will be interested in it, leading to more media coverage.

Thanks for reading!

I really hope some of you found this article helpful. If you’d like to support Ooblets development and encourage me to write more of these sorts of articles, you can become a supporter on Patreon. If you have feedback on or criticisms of this article, I’d love it if you shared them, either through comments here, Twitter, or Discord.