Looking back at my time with Assassin’s Creed Odyssey, the main thing I can remember about it is how long it was. I spent around eighty hours exploring Ubisoft’s extravagant representation of Ancient Greece, and while there’s no question I enjoyed a lot about it, specifics about what I actually did in that time only come up if I really concentrate. I can remember chatting with Socrates and hunting down cultists and that awesome battle with the Minotaur. But the immediate image I get when thinking about Odyssey is the map. The Grecian peninsula and its surrounding islands are plastered across the inside of my forehead, accompanied by an anxious sense of futility.

My brain has overridden the quality of Odyssey in favour of the quantity of it, and I can’t help wondering how much difference it would have made to my experience had Odyssey been sixty hours long. Or forty. Or even thirty. It’s like after you’ve eaten a massive Christmas dinner and all you can think about is how uncomfortable you feel because you consumed your own leg’s worth in turkey and potatoes. If I’d eaten slightly less, I’d probably be able to appreciate it more.

I’ve picked on Odyssey because its size is somewhat notorious, but it’s hardly the only stuffed platter in gaming’s relentless open-world banquet. Over the last few years, such feasts have become almost monthly occurrences, whether it’s Borderlands 3, or Red Dead Redemption 2, or whatever gargantuan virtual space is next on the list. It may seem churlish to complain about games that offer such an abundance of playtime. But it is possible to have too much of a good thing. While attending an all-you-can-eat buffet can be enjoyable from time to time, constantly binging on them simply isn’t healthy.

Why do we enjoy open-world games? A large part, for me, is the sense of freedom they offer, the feeling of chasing horizons, pointing yourself in a direction and knowing you’ll have an adventure. Of course, it’s not really freedom. It’s all been very specifically built for you to uncover. But it’s that psychological sleight-of-hand which makes open-world games so compelling. From this, it’s logical to assume that the farther you stretch those horizons, the more convincing the trick. But this isn’t true at all. It’s possible to generate that exact same sensation within a much smaller space.

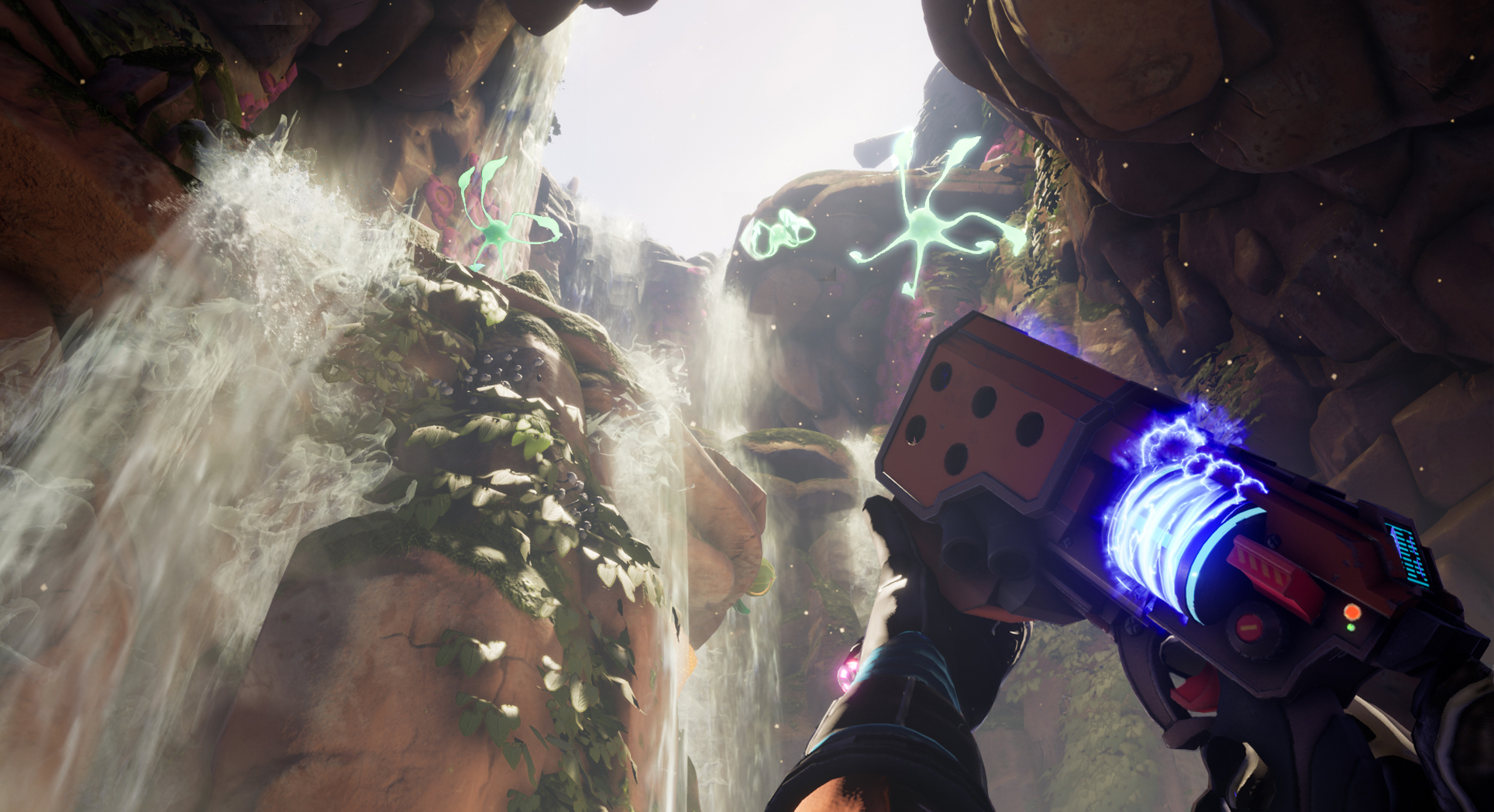

The recently released Journey to the Savage Planet is a good example of this. Depending on how thorough you are, Savage Planet’s length can range from between eight and twenty hours. But it still manages to provide both the sense of scale and the sense of freedom of much larger open world titles. What’s more, there are games even smaller than Savage Planet which also do this. Firewatch is one, and the little-known Canadian detective game Kona is another. Both games are about five hours long, and yet they both make you feel like you’re exploring a large open wilderness.

The larger an open world is, the harder it becomes to give it the foundations it needs to maintain the player’s interest.

The reason these games succeed is partly due to clever environment design. Savage Planet, for example, builds its world vertically. Not only does this mean the player moves at a slower pace, exploring a vertiginous environment feels more dramatic than travelling across a flat landscape. Kona, meanwhile, conceals the relative small size of the map by putting you in the middle of a snowstorm, and combines this with winding roads that are often obstructed or otherwise out-of-service, forcing you to take longer routes through its small world.

More important, however, the size of these games is aligned with the depth of their systems. Discovery in open world games doesn’t just happen at a visual and environmental level. It also happens at a mechanical level. The ways players can interact with the world, and the ways the world can interact with itself, are just as important as the number of square kilometres an open world covers.

The biggest gaming news, reviews and hardware deals

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

The larger an open world is, the harder it becomes to give it the foundations it needs to maintain the player’s interest across the duration. At the 80+ hour point, an open-world game needs to have the questing design of the Witcher 3, or the toolkit and AI responsiveness of Metal Gear Solid V, to comfortably keep the player engaged. Otherwise, you end up with a situation where a game carries on long after the player has bled its play potential dry. Much as I enjoyed Assassin’s Creed Odyssey, I’d had enough of clearing fortresses well before the end of the game.

When you hit this point, an open-world game ceases to be entertaining and starts to become a chore, a looming obstacle that takes up mental space which you feel obliged to clear, but have no real motivation to. Meanwhile, the next huge open world game might already be sitting in your game library, tapping its foot and checking its watch, compounding that urge to finish a game despite no longer enjoying it so that you can keep up with whatever’s next.

Once an open world game runs out of mechanical or narrative steam, it can shift from being a pastime, a way to relax, into being work, a mental stressor. Of course, the point of switchover isn’t the same for everyone. Some people can happily play the same game for hundreds, even thousands of hours without getting bored. But games often treat that kind of player commitment as typical when it’s actually fairly rare. After all, if you’re committing hundreds or thousands of hours to a game, it’s probably the only game you commit to like that.

Once an open world game runs out of mechanical or narrative steam, it can shift from being a pastime, a way to relax, into being work.

Many games try to artificially encourage that kind of stayability. A common element of games-as-service design is to offer the player regular rewards in exchange for their time, typically in the form of loot and/or character upgrades. Personally, I’ve always been skeptical of this kind of design, at least when these elements are frontloaded as one of the game’s main features. If the emphasis of a game is on the rewards it is giving you, rather than how you can then use those new tools, powers, or whatever for more creative play, then the game is essentially buying you off—encouraging you to run around the same feedback loop over and over, just in shinier boots.

I’m not saying I want all games to be five-hours long. Some games need a decent chunk of time to carry through their full arc. It’s more about acknowledging that, just like films, books or TV shows, games can be too long as well as too short, and that it’s better for a game to end while you’re still enjoying it, than twenty hours beyond the point you wanted to put it down.

Rick has been fascinated by PC gaming since he was seven years old, when he used to sneak into his dad's home office for covert sessions of Doom. He grew up on a diet of similarly unsuitable games, with favourites including Quake, Thief, Half-Life and Deus Ex. Between 2013 and 2022, Rick was games editor of Custom PC magazine and associated website bit-tech.net. But he's always kept one foot in freelance games journalism, writing for publications like Edge, Eurogamer, the Guardian and, naturally, PC Gamer. While he'll play anything that can be controlled with a keyboard and mouse, he has a particular passion for first-person shooters and immersive sims.