On Her Story's 5th birthday, Sam Barlow looks back at his breakout game—and talks about what's next

How the Silent Hill series, and a cancelled Legacy of Kain reboot, led to the creation of Her Story.

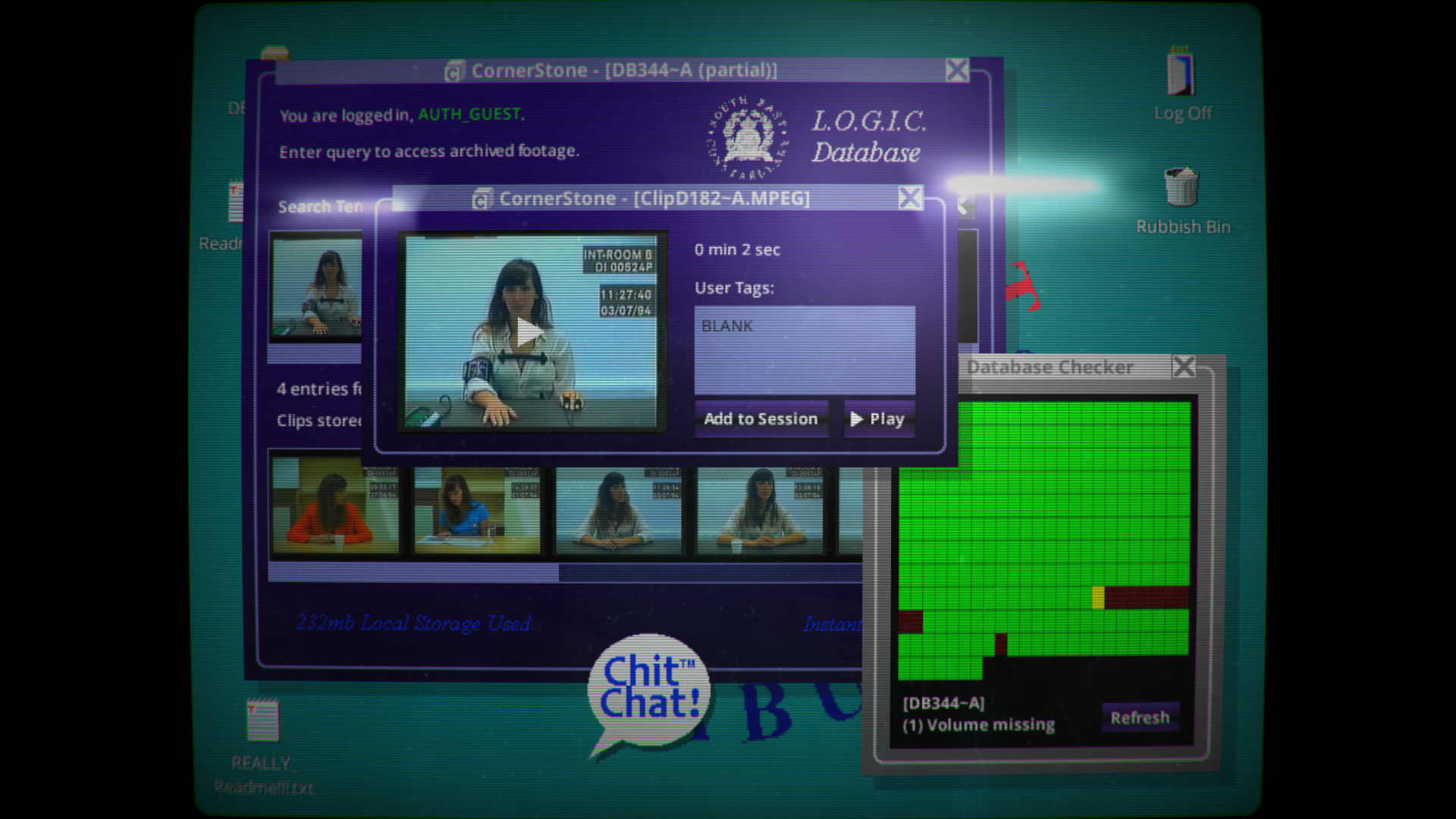

It's been five years since the release of Her Story, Sam Barlow's clever, subversive police procedural. And now the developer is teasing something new, with a cryptic Steam page that, well, doesn't reveal much. But in a chat with Barlow about the making of Her Story and how its success has impacted his life—the highlights of which you can find below—he told us a little about what can expect from this intriguing, as yet unnamed third game.

The (very) early days

Sam Barlow: "As a very young child I would max out my library card, and the library cards of my two siblings as well. I liked to read lots of books. I'd fill half of my book allowance with pulp sci-fi from the '60s and '70s. Too much Philip K. Dick. But I would balance that out by reading modern literature. Especially in translation, 'cause I knew that was the stuff that was more worthy."

"I grew up reading a lot of experimental stuff, and so telling stories in weird ways, or fragmented ways, was something I always enjoyed. I made a weird text adventure called Aisle in 1999, which became about telling lots of small, tiny stories that all intersected at a single point in time. So that was definitely something I enjoyed playing with."

Welcome to Silent Hill

"I didn't mentally make the connection between the cool interactive fiction I liked and had been writing, my interest in storytelling, and the fact I now had a job making videogames. This was partly because of the games I was making. My first job was working on a Serious Sam game for the GameCube. I made a terrible motocross game. I had the pleasure of being the lead designer on the movie tie-in game for Nicolas Cage's Ghost Rider."

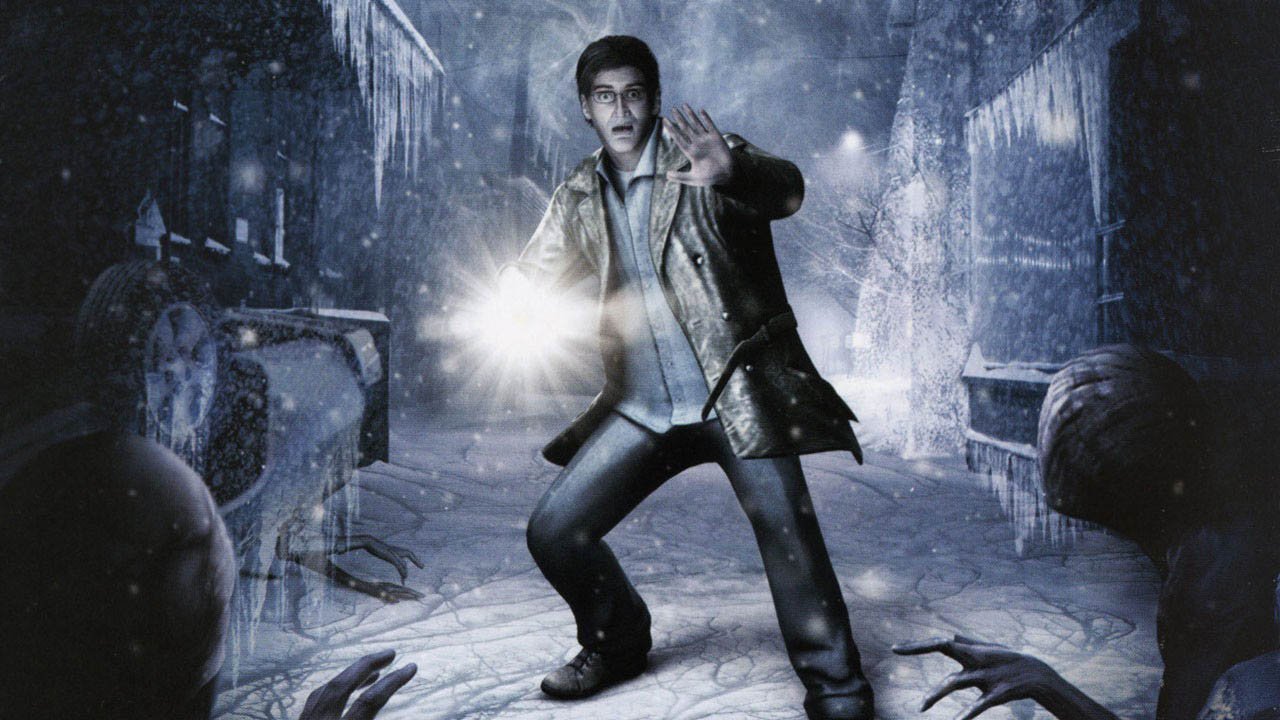

"But at some point, through a huge amount of luck, and also probably some effort on our part, we got to work on Silent Hill. The first Silent Hill game we worked on, Origins, was started by a different group of people, and it was in a terrible state. When we took it over, I think we had six months to finish it, and they'd already spent half the money. So we were told to just finish the thing. But me, and particularly the lead artist Neale Williams, were thinking: aren't Silent Hill games usually really good?"

"We didn't wanna make the first bad Silent Hill game. Not just bad, but awful. Especially when it was an origin story—which was a terrible idea, by the way. The first Silent Hill already tells an origin story. We had very little room to manoeuvre, but we did our best. And part of doing our best was not in any way attempting to change the classic structure. The story would be told by the environment, and through diaries. You'd feel like you were picking them up randomly and out of order, but it was clearly intended by us to deliver a certain emotional heft."

"We were locked into some cliched stuff when we started work on the project. There was a level set in an asylum, but there was no reason for you being there. You were just randomly walking through an asylum. We thought this location should probably tie into the character's story, so we set it up so that the last piece of paperwork you find is a log of your mother being admitted there, and a doctor's note about how well she was doing. And suddenly it was so much more poignant. I enjoyed doing that."

The biggest gaming news, reviews and hardware deals

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

Asking questions

"Then I worked on Silent Hill: Shattered Memories, which was the first time I'd been able to start with a blank slate and tell the story I wanted to tell. That game was both my love letter to, and my parting of ways with, the immersive sim genre. Growing up I was obsessed with these games. That idea of systemic complexity and total immersion. I loved Metroid Prime with its contiguous world and sense of place. The way backtracking built up your familiarity with the world. A lot of the pleasure in that genre comes from building a mental model of the environment as you play."

"With Shattered Memories, I was trying to create a super immersive world with all the obstacles to that immersion removed. But this was the point where I was starting to question some fundamentals about how videogames work. It was interesting that a lot of the games released at that time, which were heralded for their storytelling, were doing the archaeological thing."

"In BioShock you show up and all the interesting story has happened, and you're there picking up the pieces. Similarly, in Gone Home, the character you play as is not the one having the interesting story. I love the exploratory elements and atmosphere that comes from walking around a 3D world. But I'm also mindful that a lot of the storytelling is being done through audio and literary devices. So I felt there was a conflict there."

The AAA team

"But the big thing that precipitated Her Story was spending three years as the writer and director of a Legacy of Kain reboot. A very ambitious AAA game that was essentially Zelda, but if HBO made it. This utterly failed to work, because people wanted the game to be like Uncharted. They told us they wanted a dark, intelligent single-player game, but we'd get feedback from greenlight meetings (that we were ourselves not attending) and we'd be reading the subtext, thinking: are you sure that's what you want? Then they started talking about multiplayer and DLC."

"Square Enix was juggling some amazing IP. Hitman, Tomb Raider, Deus Ex. But none of them had been huge commercially. Even a huge phenomenon like Tomb Raider. And so after three years, the Legacy of Kain game was cancelled. After that, I spent a year, at the same company, pitching and desperately trying to figure out how to get a videogame made. They were really focused on mobile and free to play. Free to play was blowing up, so why would they spend $50 million on a single-player game? And so we shifted to pitching smaller, story-driven things, around the time these kinds of cool, digital-only games were becoming popular on XBLA. But the economics of it never made sense, which was frustrating."

People problems

"I was really interested in making character-driven, narrative-focused games, and the kinds of things I wanted to do meant some element of performance. Gone Home was created from the concept of telling a story if you can't have lots of characters and cinematics. Then games like Tacoma and Everybody's Gone to the Rapture used holograms and ghosts. But this wouldn't work for me. For the stories I wanted to tell, I would have needed millions of dollars for motion capture. I spent a year on Legacy of Kain directing performance capture with a really cool cast, so I knew how that worked and the costs and everything."

"I thought I could parlay my Silent Hill: Shattered Memories cred into funding an exploratory horror game on Kickstarter. But I knew that if I did that, I'd be making a compromised version of the story I wanted to tell. It would be the $100,000 version of a $5 million game. Every decision would come from that restriction. So I didn't want to do that. I really wanted to make something that felt like it was the best version of itself."

Making a case

"I honed in on the idea of a detective story. In every other genre, the evergreen thing is crime fiction. There was L.A. Noire and Phoenix Wright, and I loved the old Infocom detective games. But every time I pitched publishers, they really didn't get it. No matter how many examples I could point to of how successful cop shows and thrillers were, they said it doesn't work in videogames. I think the thing they didn't like was that it's intensely character-driven. It almost just comes down to conversations. The stories are set in the present day, so you don't have laser guns and spaceships. But I kept developing the concept."

"I decided that it would be about the interrogation. As a teenager I was obsessed with Homicide: Life on the Street, and I watched a lot of The Bill growing up. In those shows, the high point of the drama was always in the interrogation room, with characters facing off against each other. There was an episode of Homicide called Three Men and Adena, which I think won an Emmy (it did), and the entire episode was set in the interrogation room."

"I decided that focusing on the interrogation room in the game was a very smart thing to do. It reduced the scope. I didn't need to think about car chases, locations, or other things that would destroy my indie budget. And there'd be no distractions. There's that weird conflict in L.A. Noire where you can drive a car around these fully simulated streets, and can accidentally run over pedestrians, while also doing the crime stuff. It was also a way to do something most games don't focus on, which is conversation."

Slowing things down

"An early version of Her Story was too opaque. It dropped you in and there was an empty search window in front of you. Just a blinking cursor. And at some point I thought if I put the word MURDER in there, that takes something that is outrageously dull—this computer desktop—and injects some spice, some foreshadowing, into it, and leads you on a journey. But that was a huge part of the appeal of the idea of Her Story for me. To give players something that they had to work at and dig into."

"At the start of Silent Hill 2, they force you to walk along a misty path for a very long time. Their intention there was to bed you into the game, to make you feel like you're crossing through into a different place. So in Her Story, we had the title screen take a while to drop you in. It forces you to take a moment and be drawn into the world, and let everything else fade away. The title screen, the aesthetic, and that first keyword make you feel compelled to dig, and you pretty rapidly have threads to pull at."

A runaway hit

"With Her Story I wanted to make something extreme that I would be proud of, and that would be unique. I was very frugal in how I made it, and my expectations were reasonably conservative. And then it ended up doing extremely well. The run of awards shows was ridiculous. It was always The Witcher 3 versus Her Story and some other AAA thing. Usually the indie game awards and the 'proper game' awards were carefully kept apart. But Her Story made those barriers disappear. It even appeared in the mainstream press. People were able to understand this weird game in a way they couldn't understand 99 percent of other games, which led to all kinds of Hollywood meetings, film festivals, and other fun stuff."

The next game

"Off the back of Telling Lies, we took on some investment that means we can fully fund and publish the next thing. And to keep things interesting for me, it's ten times more ambitious. We haven't figured out exactly how, but we're gonna try to talk about this game early, in a way that will keep it mysterious. As a concept it's very mysterious. It's a return to both horror, in the loose sense. A lot of the stuff I did in my personal life pre-Silent Hill was in the darker, psychological vein. Silent Hill was a great vehicle for that. When we were making it, in 2007 I think it was, that was the only IP in the world that would allow you to make a videogame that cared about a character's inner thoughts."

"Having done Her Story and Telling Lies, it's exciting for me to return to that. It also unlocks a lot of fun ideas, and a chance to interrogate the relationship between the game and the player. I don't want that to be adversarial, but with some push and pull. I want to see what happens when you put constraints on the player, or when you push them in a direction that isn't entirely comfortable. And once you get into horror, there are even more options to do that in a game. Her Story and Telling Lies were made up of realistic found footage, but people still call them interactive movies. So in this next project, let's tackle movies."

"Let's deconstruct what a cinematic visual is. I was an obsessive cinephile pre-games industry, back when it was hard to find movies. I'd constantly be recording stuff off Channel 4 at 3 am. I had an extremely nerdy film diary that I would fill out. But I've been deliberately trying to avoid that when making games. When I pitched Telling Lies to Logan Marshall-Green, he really liked that the first page of the screenplay described it as an anti-movie. So I've been very mindful of knowing what cinema is and how it works, but trying something different."

"But working with a great crew on Telling Lies, seeing what they could do with me tying one of their hands behind their backs, and seeing what the actors could do when I took them out of their comfort zones, I'm now excited about working with them on something on their own terms. This project is really about interrogating how stories are told in cinema, from the full creative process to the act of watching. When I start a project, it's partly an excuse to do fun research. And we've been having some very interesting conversations on this one. It's gonna be a really cool thing."

If it’s set in space, Andy will probably write about it. He loves sci-fi, adventure games, taking screenshots, Twin Peaks, weird sims, Alien: Isolation, and anything with a good story.