Observer's cyberpunk hallucinations are like being trapped in a Tool video

Our thoughts on the opening hours of the Polish sci-fi detective story from the team behind Layers of Fear.

My favorite cyberpunk stories are usually the ones about criminals and outsiders in situations way out of their league, and my least favorite are about badasses with future-guns shooting a bunch of cyborgs or robots or whatever. In between there's the third kind of classic cyberpunk story, in which an investigator gets too involved in a case and uncovers something they shouldn't while also confronting a bunch of philosophical questions about what it means to be human. It sounds specific, but that's genre for you. Observer tells that third kind of cyberpunk story, and is about as pure a version as you can imagine.

Developed by Polish studio Bloober Team and launching August 15, Observer is set in Krakow in the year 2084. You play Daniel Lazarski, voiced by Rutger Hauer—presumably cast on the strength of his performance in an iconic cyberpunk detective movie, by which I mean Split Second of course—who has been cybernetically enhanced to perform neural interrogations, plugging himself into people's brainchips. It's as if he's walking around inside their subconscious, observing their memories and secrets. Observers are basically cops that can climb into your head. Yeah.

Third eye

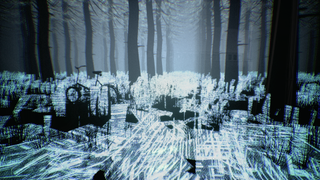

These hallways of the mind are represented as literal hallways. Bloober's previous game was Layers of Fear, a first-person horror experience full of mindfuck trickery, and that lineage is obvious when you perform a neural interrogation and find out it's actually super claustrophobic in someone else's head. In the part of Observer I've played—the opening 10 hours or so, most of which takes place in an apartment building with a bad case of the murders—everyone I plug into is either dying or dead, and their mental landscapes are surreal.

One victim works for the same corporation funding the Observer task force, and has been stealing data from them. Plugged in, I experience their fading consciousness as an Orwellian computerized job interview and a stealth sequence in an open-plan office, but also through more metaphorical scenes. In one, I have to cross a field where data cables grow like corn, while eye-in-the-sky camera drones patrol overhead.

At its best, the hide-and-seek pursuit stuff is reminiscent of Alien: Isolation, and at its worst it's every instafail stealth sequence shoehorned into a genre where it doesn't belong.

Sometimes things from outside their brain leak through, in such forms as memories of Dan's missing son suddenly overlaying the scene or a mysterious figure pursuing me through the dreamscapes. At its best, the hide-and-seek pursuit stuff is reminiscent of Alien: Isolation, and at its worst it's every instafail stealth sequence shoehorned into a genre where it doesn't belong. Two of the neural interrogations I’ve played so far have involved sneaking. By the second I was hoping there wouldn’t be more.

And wow does it get weird. Rooms repeat, I get trapped in mazes. Chairs and buckets hang in the air. Shadowy people-shapes, abstracted fuzzing representations of humanity, hurry past or block doorways. Sometimes lumps of flesh grow on things. I follow a floating screen and a glowing deer, walls explode into pigeons, and everything goes fish-eyed or wobbly like a Wayne's World dissolve. It's like being trapped in a Tool video. When the walls are breaking into shards that hang in the air or screens are flashing images of Polish dumplings at you, it’s trippy enough to invoke a full-on Keanu “Woah!”

Mostly though, it's hallways. It feels a lot like P.T., and after a while I start to develop a kind of psychedelic fatigue. More floating chairs? More old-timey black and white TV footage? Cool, cool. I'm glad to get back to the real world, even though it's a dystopian future Poland controlled by a corporation. Here, it's less horror and more adventure game, all investigating crime scenes and quizzing witnesses.

The biggest gaming news, reviews and hardware deals

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

For the investigation scenes, Dan's cybernetic eyes kick in and I start scanning everything like I'm Batman with the detective vision, trying to piece together clues and find a way out of this apartment complex. It's under lockdown due to a disease called the nanophage because of course there's a cyberplague, and automatic security has trapped us all here together.

Eulogy

It's a long time to explore the one slum (and attached tattoo parlor), but worth it to get to know so many inhabitants. Their faces are obscured by crusty vidscreens because most of the tech in 2084 Poland looks like it comes from 100 years earlier (they even play a pixelated puzzle dungeon game straight off a Commodore 64), and through those screens I talk to a bunch of scared people hiding in their rooms, trapped in here with me.

They all have their stories, whether it's the guy going through holographic projector withdrawals or the widow who lost her wife to the nanophage. Cyberpunk is at its best when it's engaging with characters who usually get ignored in favor of people who fly spaceships. And even though Dan is a fancy cybered-up future cop, he spends a lot of time observing ordinary folks. There's even a confused guy knocked out of an extended VR session by the lockdown who’s convinced he's a starship captain.

My favourite character in Observer so far is another ordinary person, a janitor. At first, my Dan is rude to him, a scrappy guy outfitted with junk cyber-parts, but then I get onto the janitor's computer and read his emails—because of course a cyberpunk game is about reading everyone's email. Turns out he's a war veteran whose current job excludes him from the veteran's group that used to pay for upkeep of his prosthetics. It's a common, relatable story: the people who most need help are ineligible for it due to bureaucratic nonsense they’re helpless against.

I see the janitor again later and choose a friendlier line of dialogue, and mumbly Rutger Hauer warms up to him. We stand in the courtyard while it rains, Krakow's skyscrapers and hologram ads on the other side of a wall we can't cross while we're stuck with the pigeons and glitching augmented reality data overlays that coat the walls like digital glaze. It's a moment, you know?

When Observer isn't being David Lynch's Blade Runner it's a detective game where you don't have a gun and can't fall back on violence, an adventure game that's all about talking to people, guessing codes, hacking computers, and opening doors. Like all mystery stories, a lot will depend on its finale and whether it ties up the loose ends in a satisfactory way. I'm not allowed to tell you what happens after you make it out of the apartments, so I stopped playing there to write this, but I'm itching to go back and hunt around for more near future philosophy, or at the very least, I hope to have more honest conversations with lonely cyborgs.

Jody's first computer was a Commodore 64, so he remembers having to use a code wheel to play Pool of Radiance. A former music journalist who interviewed everyone from Giorgio Moroder to Trent Reznor, Jody also co-hosted Australia's first radio show about videogames, Zed Games. He's written for Rock Paper Shotgun, The Big Issue, GamesRadar, Zam, Glixel, Five Out of Ten Magazine, and Playboy.com, whose cheques with the bunny logo made for fun conversations at the bank. Jody's first article for PC Gamer was about the audio of Alien Isolation, published in 2015, and since then he's written about why Silent Hill belongs on PC, why Recettear: An Item Shop's Tale is the best fantasy shopkeeper tycoon game, and how weird Lost Ark can get. Jody edited PC Gamer Indie from 2017 to 2018, and he eventually lived up to his promise to play every Warhammer videogame.