Nine of the most important pieces of PC gaming technology

Considering the PC platform got its start way back in 1981, it’s no surprise that in the more than three decades since, it’s played host to a stunning array of technology. While some of these technologies, like Bubble memory or Firewire, have come and gone with barely a whimper, other technologies have left an indelible imprint on the future of the platform, particularly when it comes to gaming.

What follows is a snapshot of the PC's hardware history, highlighting some of its most important pieces of technology. Look at the parts in your PC, and the accessories on your desk, as descendants of these trailblazers. Pay attention to how much each one costs, and you may gain a new appreciation for the price of today's equivalents. Can you imagine paying $475 for a mouse? Well...

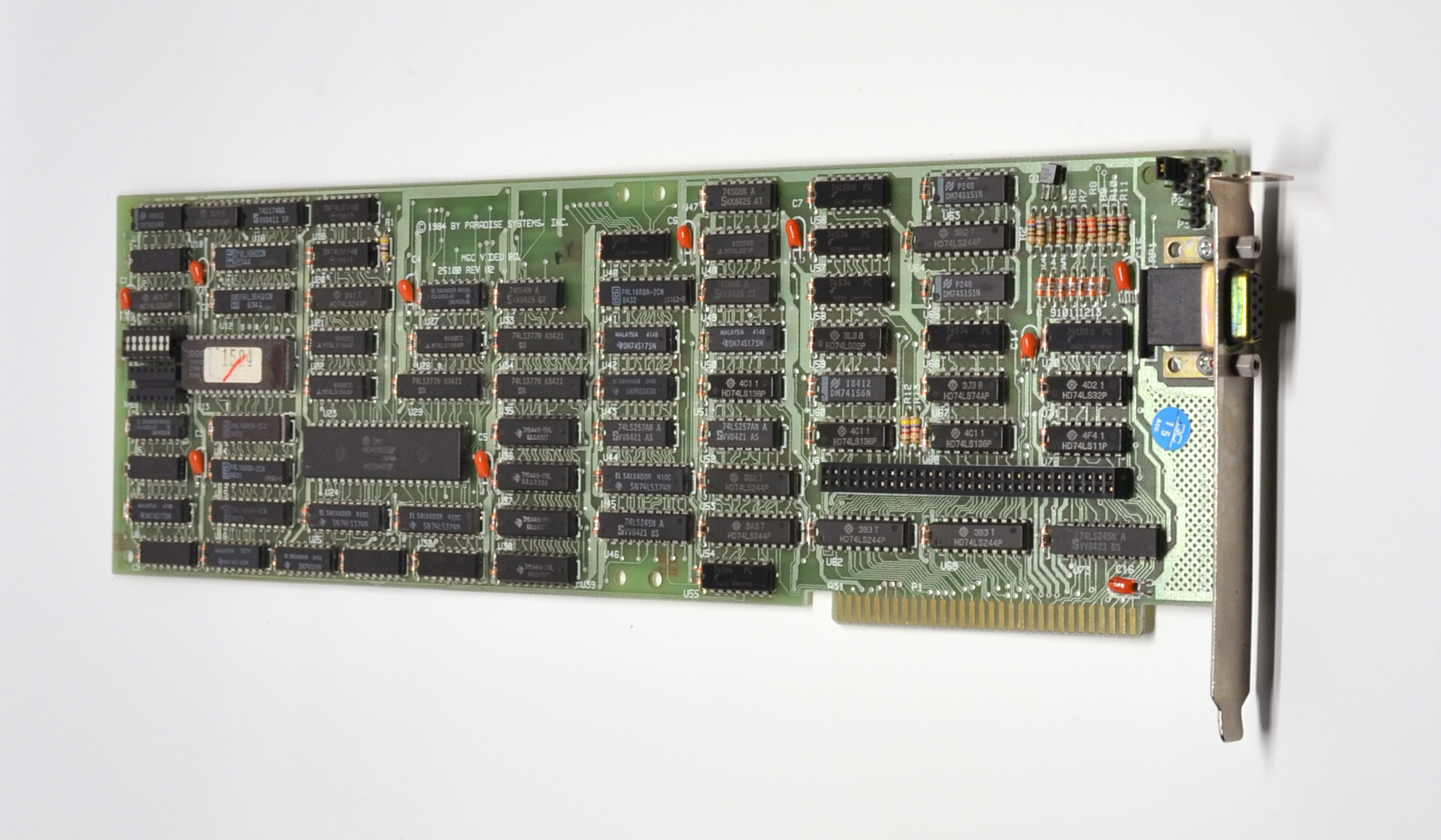

IBM Color Graphics Adapter

The Paradise Systems Modular Graphics Card pictured above, released in 1984, was the first CGA card that could output to a monochrome monitor. Considering the base configuration was $395 (in today’s dollars, over $900), being able to save up for the future purchase of a color monitor and still benefit from a graphical display in the mean-time was a nice feature.

When IBM released their seminal PC 5150 in 1981, prospective buyers had a choice of a low cost Monochrome Display Adapter (MDA) or a more expensive Color Graphics Adapter (CGA). While the MDA card was limited to a single, graphics-free text mode, the CGA card, with its 16k of video memory, opened up the burgeoning PC standard to the possibilities that multiple resolutions and color graphics could offer, including enhanced gaming.

Although many CGA games were rendered in a resolution of 320x200 in four colors, other modes were available, including a high resolution 640x200 monochrome mode, and a low resolution 160x100 mode that gave access to all 16 colors from the hardware pallet. While use of a digital RGBI monitor like the IBM 5153 retained the integrity of the card’s color output, connecting to a television or monitor over an analog composite connection created color artifacts. This peculiarity of the NTSC signal was often exploited by game makers to effectively display far more than the four, often garish, available colors over RGBI.

Although technically modest, as the first graphics card option for PCs, and one that set the precedent for various clones and the vastly improved graphics cards and standards that would follow, CGA’s influence can’t be overlooked. And even with the introduction of the next two major standards, Enhanced Graphic Adapter (EGA) in 1984, and Video Graphics Array (VGA) in 1987, CGA would continue to see software support into the early 1990s.

The Microsoft Mouse

Image via Flickr user Marcin Wichary.

Microsoft released their first mouse in 1983, complete with heavy steel ball and an InPort ISA interface card to allow it to connect to a PC, all for around $200 (about $475 in today’s dollars). Although not the first PC mouse, it represented an important first step for a company whose future operating systems would come to rely on the handy input device.

Although there was little reason to own a mouse well into the 1980s, as Microsoft’s Windows evolved, and specifically after the release of Windows 3.0 in 1990, it eventually became a fixture for PC owners everywhere. Thanks to its growing ubiquity, an ever-increasing number of games began to support the mouse, with certain game types, like adventure games, first person shooters, and real time strategy able to feature far more intuitive and precise interfaces as a result. And in spite of the mouse seeing limited use with game consoles and other devices, it’s still the one control method that PC gamers can proudly claim as their own.

The very first mouse actually predated Microsoft's by about 20 years; legendary inventor Doug Engelbart first protoytped it in 1964. It wasn't until the Razer Boomslang in the late 1990s that we started to see mice specifically designed for gaming, which led to Logitech's 2005 mouse the MX518, the most popular gaming mouse of all time.

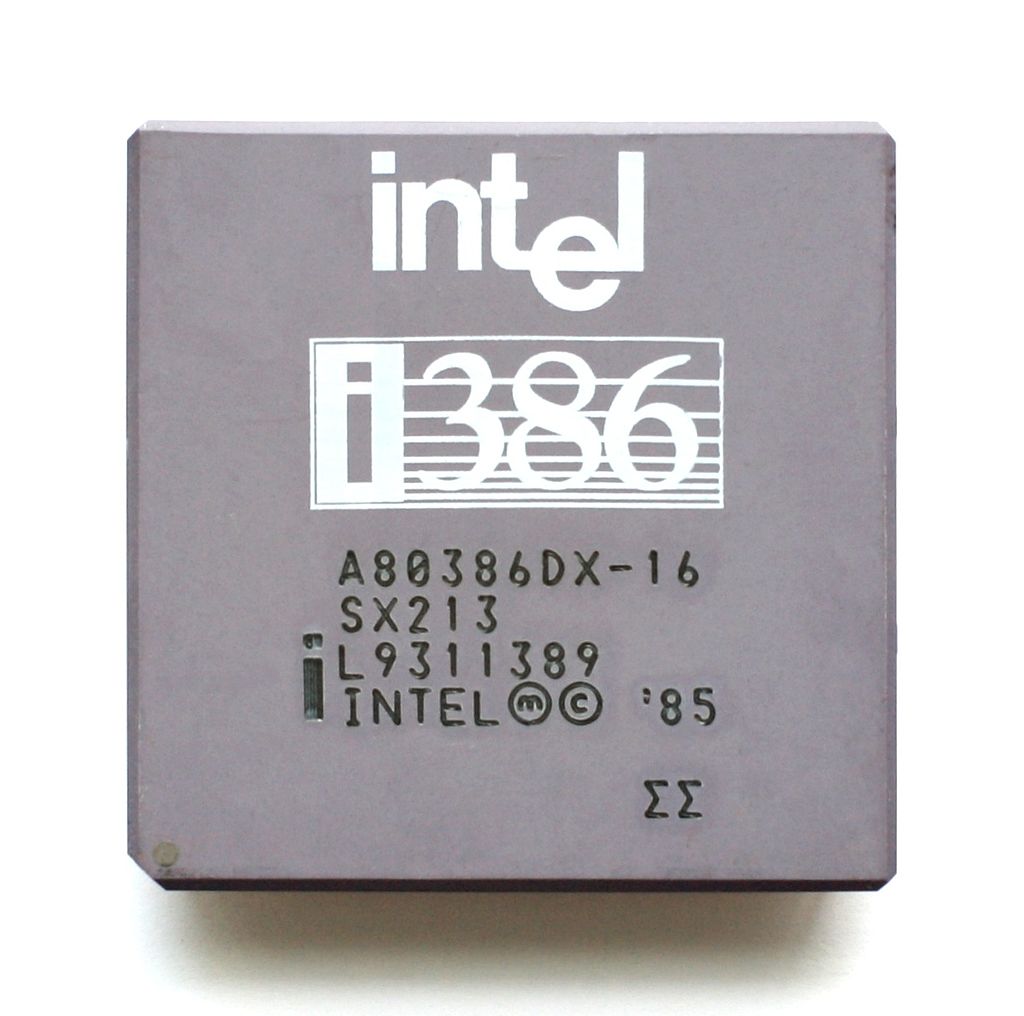

Intel 80386 Microprocessor

The original IBM PC 5150 shipped with an Intel 8088 8-bit microprocessor clocked at 4.77 MHz. IBM and most clones would stick with this processor until the release of the IBM PC AT 5170 in late 1984, which shipped with an Intel 80286 16-bit microprocessor clocked at 6 MHz. This new microprocessor, which would eventually max out at 25 MHz, featured a significant performance boost over its predecessor, while still maintaining full hardware compatibility. It was however the release of Intel’s even more powerful 80386 32-bit microprocessor that would come to represent the biggest impact in the world of IBM PCs and compatibles.

Introduced in late 1985, the 80386 would first be used the following year in the Compaq Deskpro 386. It would take another seven months for IBM to follow Compaq’s lead. As such, the 80386 represented a changing of the guard in the world of IBM PCs and compatibles, where, from that point forward, it would be a company other than IBM that would set the technical standard for others to follow. This shift paved the way for ever impressive technical milestones at an increasingly lower cost, helping to further democratize standards and eventual remove IBM from the equation entirely.

The 386, as it was more commonly called, was also a hugely popular processor for gaming, but not until the early 1990s when it became more affordable. Most PC games in the early 90s required a 386 until the minimum spec moved on to its successor, the 486. For a look back at some of those games, check out this wonderful compilation of 1994's DOS library.

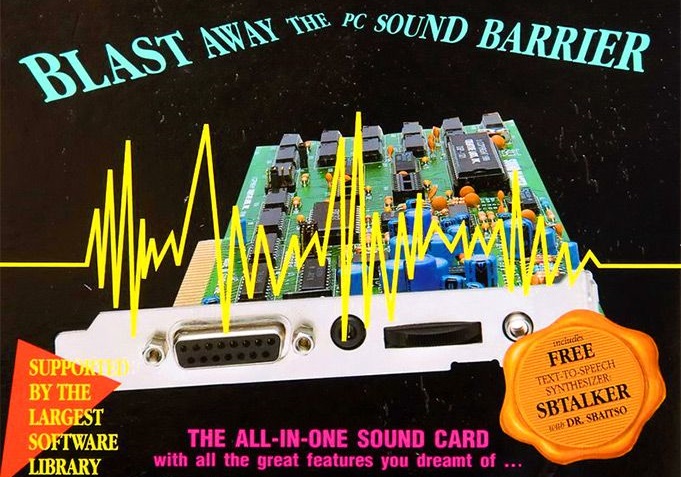

Sound Blaster

The Sound Blaster Pro pictured above, released in 1991, was just one in a long line of successful multi-function sound cards from Creative Labs.

While several other, less expensive computers already had decent-to-excellent sound capabilities, IBM chose to release their original PC 5150 with nothing more than a tinny internal speaker meant to produce simple beeps. This pivotal design decision meant that, for the most part, games for PCs and compatibles were saddled with sub-standard sound even as graphical standards evolved to meet or exceed that of rival computers. Although many workarounds and add-ons were attempted, it was not until the release of the AdLib Music Synthesizer Card in 1987 that the first widely supported general standard began to emerge.

Unfortunately, the AdLib card was designed primarily for FM Synthesis music, relying on the lowly PC speaker to continue to produce sound effects. It was only after Creative Labs launched its first Sound Blaster card in late 1989 that a card, and more importantly a standard, began to emerge that could not only produce AdLib-compatible music, but also leverage a Digital Sound Processor to play back sound samples. In a final master stroke, Creative Labs included a game port right on the same card, so those gamers who liked to use a controller could save an internal slot in their computers, adding even more value to, and helping further adoption of, the growing Sound Blaster standard.

Although Creative Labs and others continue to make discrete audio cards to this day, the quality of motherboard- and USB-based audio have rendered those cards mostly irrelevant. Nevertheless, the Sound Blaster series represented a critical turning point in the evolution of sound on the PC, finally bringing the platform in line with its competition and helping it to take its rightful place as the definitive gaming platform.

CD-ROM

The 7th Guest and Myst (pictured above) were the first two killer apps on CD-ROM.

From the early to mid-1980s, PC gaming was relatively simple. You booted your one 5.25” floppy disk and played your game. As time passed and games grew in audio-visual and other areas of sophistication, additional floppy disks might come in the box, as well as the handy option for hard drive installation. Unfortunately, game sizes were soon evolving faster than floppy disk capacities, at times requiring the juggling of a half dozen or more disks for just one game. Fortunately, by the early 1990s, CD-ROM drives and their associated optical media started to become affordable.

Although initially limited to 1x or 2x transfer speeds (about 150 – 300 KiB/s), having around 650 MB available per disc—which was bigger than most hard drives at the time—was a boon to game developers. All that space meant that not only could all game data once again come on a single disc, but the promise of true PC multimedia, including generous amounts of video, could finally be realized.

If you ever had to install Windows 95 from 13 floppy disks, the advent of the CD was a wonderful thing. Of course, the same goes for the DVD, but that's another story.

As the first inexpensive mass storage device, CD-ROM drives were a critical transitional technology. They helped bridge legacy media-based computing paradigms to today’s digital paradigms, where outsized hard drives and practical cloud storage are now the rule.

3dfx graphics cards

The Apollo 3Dfast II, pictured above, was a late model Voodoo2 PCI card that could double its 3D processing power when paired with another card of the same model via a Scan Line Interleave connection. A separate 2D card was still required in such a configuration.

Choice is usually good, but not when that choice can be overwhelming. That was the situation with the first 3D PC cards that were available in the mid- to late-1990s, with various manufacturers attempting to establish their own incompatible standards. This dispersion meant that game developers didn’t know which 3D hardware or application programming interface (API) was safe to support, delaying significant advances in hardware-based 3D game development.

This all changed when 3dfx released its Voodoo Graphics chip in 1996, along with a high performance companion API called Glide. What followed were a series of low cost Voodoo-based graphics cards that would set an early standard for both gamers and game developers to rally around, allowing the PC platform to once against flaunt its technical advantages over purpose-built 3D consoles like the Sony PlayStation and Nintendo 64.

While the reign of 3dfx and Glide was short-lived, only lasting up to the turn of the century, it was an important learning experience for the industry and a critical bridge until the transition to more universal 3D APIs like OpenGL and Direct3D became practical.

In its short history, 3Dfx also had some infamous magazine ads.

USB

Although deceptively simple looking, the USB connection has helped to make expanding the PC easier for everyone, revolutionizing the platform.

Before USB interfaces started to proliferate in the late 1990s, keyboards, mice, game controllers, and many other peripherals and accessories were already PC gaming fixtures. Unfortunately, prior to USB becoming a PC standard, each new addition often required its own interface card or unique connection. This also often meant manually setting an interrupt request (IRQ) or jumper, and then hoping the operating system and individual software would allow it to both work and peacefully co-exist with other devices. USB, on the other hand, allowed for a whole range of devices to use the same connection type and for the host PC to intelligently allocate the necessary resources to many more devices than was ever possible before.

Perhaps the best part of the USB standard is that like the PC platform itself, it’s constantly evolving to be faster and ever more capable, all while maintaining excellent backwards compatibility. So while we might have spent a bit too much money on procuring just the right mechanical keyboard or high DPI mouse, there’s a good chance those devices will be just as usable with whatever computer you have a decade from now as they are with your PC today.

Flat panel displays

Displays based on cathode ray tube (CRT) technology were around since the beginning of the 20th century, so were a natural pairing with the rise of personal computers in the mid-1970s. Over the decades that followed, resolution, color range, and screen sizes continued to improve. Unfortunately, because of the nature of CRT technology, the bigger the screen, the more power hungry, bulky, and impractical they became, with, for instance, monitors with 20” screens having a similar 20” depth and weighing around 30 pounds.

Cue the flat panel display, which, by the late-1990s, were competitively priced with their CRT counterparts. While early flat panels suffered from motion blur and limited color range, the technology soon improved, eventually becoming desirable to even the most demanding PC gamer. With minimal bulk and weight, these digital marvels make having oversized single screens or multi-monitor setups practical, with high resolutions the older analog CRTs could only dream of.

For years, the diehards among us missed the flexible resolution support and responsiveness of tube-based displays, and its true LCD flat panels have had their drawbacks. But recent advancements like 144 Hz response times, adaptive refresh, 4K resolution and panels with superior color quality have gone a long way towards healing those old wounds.

Solid state drives

The quest for better PC performance is all about eliminating bottlenecks. While nearly every other PC component had a generous reduction in size with a similar increase in performance, hard drive technology based around physically rotating discs was starting to drag down overall system performance. Fortunately, just as it seemed we’d have to suffer through stagnate hard drive performance, cost-effective non-volatile computer storage based on flash memory came of age in the late 2000s in the form of solid-state drives (SSD).

While rotating disc drives still offer a higher storage capacity for a lower price than their SSD counterparts, the higher data transfer rates, greater reliability, and lower latency and access times of SSD means that we can save the rotating disc drives for secondary storage, where their impact on overall system performance can be minimized. In 2016 SSDs are pushing transfer speeds even further by moving beyond the ancient AHCI standard behind SATA in favor of NVMe, which will allow them to reach gigabit speeds that hard drives have never even dreamed of.

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Every Friday

GamesRadar+

Your weekly update on everything you could ever want to know about the games you already love, games we know you're going to love in the near future, and tales from the communities that surround them.

Every Thursday

GTA 6 O'clock

Our special GTA 6 newsletter, with breaking news, insider info, and rumor analysis from the award-winning GTA 6 O'clock experts.

Every Friday

Knowledge

From the creators of Edge: A weekly videogame industry newsletter with analysis from expert writers, guidance from professionals, and insight into what's on the horizon.

Every Thursday

The Setup

Hardware nerds unite, sign up to our free tech newsletter for a weekly digest of the hottest new tech, the latest gadgets on the test bench, and much more.

Every Wednesday

Switch 2 Spotlight

Sign up to our new Switch 2 newsletter, where we bring you the latest talking points on Nintendo's new console each week, bring you up to date on the news, and recommend what games to play.

Every Saturday

The Watchlist

Subscribe for a weekly digest of the movie and TV news that matters, direct to your inbox. From first-look trailers, interviews, reviews and explainers, we've got you covered.

Once a month

SFX

Get sneak previews, exclusive competitions and details of special events each month!