MrBeast's 'charity porn' shows the morally complicated reality of YouTube philanthropy

The creator's latest hit video was about curing the blind, but people don't think he's the second coming.

In our perpetually polarized world, even curing the blind can spark a days-long internet fracas. With 130 million subscribers, YouTuber Jimmy "MrBeast" Donaldson has perfected the art of going viral in a way almost no-one else has done. Three days ago he did it again, but this time the reaction hasn't been quite what MrBeast was expecting.

MrBeast's latest piece, "1,000 Blind People See For The First Time", compresses an act that ancient people would've seen as a miracle into eight minutes of video laser-targeted at YouTube's algorithm. We see some of the recipients before and after receiving cataract surgery or other procedures that help restore sight. Per the provider SEE International, these are either phacoemulsification operations (ultrasound removal) or MSICS, a manual technique "better suited to the advanced, blinding cataracts we often see in the poorer parts of the world."

The latter operation can cost as little as $25 in other parts of the world, but it's much more expensive under most private healthcare in the US. The whole video is made in partnership with SEE International, a medical charity founded in 1974 to tackle the tragedy of people living with easily treatable blindness.

These individuals' reactions to what has been done for them are heartwarming, and of course they're caught on camera, and MrBeast makes a point of giving some participants an extra cheque for $10,000 or $50,000 dollars. It would be interesting to know how many of the 1,000 received such benevolence but, of course, this is left to the imagination. We see the stunned reaction of a 60-year-old cashier who's just had his sight restored by a random YouTuber and gets $10K into the bargain. This becomes a slightly uneasy watch after a while, maybe because it's all pretty one-note: "Watch me, a very rich man, pay for all you poor people to have your sight back."

MrBeast presumably thought this would show him purely as a beneficent philanthropist, and his usual tactics have worked as effectively as ever in helping the video reach a massive audience, but with a stunt like this it's always impossible to predict exactly how the reaction will play out online. And sure enough, this stunt has also produced considerable criticism.

"It's deeply frustrating to have to rely on a benevolent content king making feel-good videos," said TheZatzman on Twitter, "rather than addressing the root causes of these problems." Others imagined the situation faced by those featured in the video. "Imagine being blind and your only opportunity to stop being blind is to expose a very intimate, emotional moment of your life with millions of people for the sake of MrBeast," said CafeBeef.

"I think philanthropy is a Band-Aid on a bleeding tumor."

Anand Giridharadas

"Charity porn," says Marassenna in response to the above. "Right at the start of it they say something about how 50% of blindness is curable. Then to see them just dancing around like it's a talk show charity segment infused with the vibe of modern content tailored to our destroyed attention spans feels viscerally wrong."

The biggest gaming news, reviews and hardware deals

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

The obvious counterpoint to this criticism of the MrBeast video is that, hey, the guy cured 1,000 peoples' blindness. How many have you cured today? But this response focuses purely on the outcome, the good ends of Mr Beast's latest act of charity, and not the precise means of providing it.

There is something so demonic about this and I can’t even articulate what it is pic.twitter.com/OSpgaUxnQKJanuary 29, 2023

Political analyst and philosopher Anand Giridharadas, who also joined the chorus of criticism on Twitter, warns against "this pervasive societal habit of automatic gratitude and praise for elites who engage in various forms of do-gooding." The point is not so much that MrBeast has done demonstrable good here but the underlying reasons why he's done it in this way. Giridharadas, who's written about this subject in Winners Take All: The Elite Charade of Changing the World, has a clear view on how the ultra-wealthy use philanthropy as image-laundering and, while his chosen targets are not influencers, it is clear how a dynamic like this maps onto an individual like MrBeast.

"I think philanthropy is a Band-Aid on a bleeding tumor," Giridharadas told The Guardian in 2019. "To be sure, there's blood, and the Band-Aid helps with that. But the Band-Aid is inadequate to the underlying problem. To stretch the metaphor further: the Band-Aid may give you a false sense of confidence that the problem is being handled. In an age of extraordinary generosity from plutocrats, we are at risk of forgetting that the same class of people are also undermining the greater good every day and on an ongoing basis… In so many ways, we have outsourced the betterment of our world to people with a vested interest in making sure we don’t make it too, too much better."

By that measure, MrBeast stands out among his thousands of competitors on YouTube by being a figure who cures the blind, or gives someone an island. I don't think we can or should get into the unknowables of what motivates it, but the effect is real, and you only need to look at the comments under the video to see how well it's played with the audience. "Cleaning a beach, planting 20 million trees, curing people’s blindness," writes commenter Sports Card Junkie. "You are amazing Jimmy! Hats off, so amazing what you do to help others." Corey Tonge writes: "He's literally the most generous, life changing and inspiring creator out there... taking notes every single day from him."

Is Mr Beast monetizing people's suffering? And, even if he is, does that matter if he's ultimately still doing good deeds? We may think about cracking the spine of a moral philosophy textbook, but really we should be thinking of how altruism is complicated by being processed through the algorithm-appeasing formula of a YouTube video.

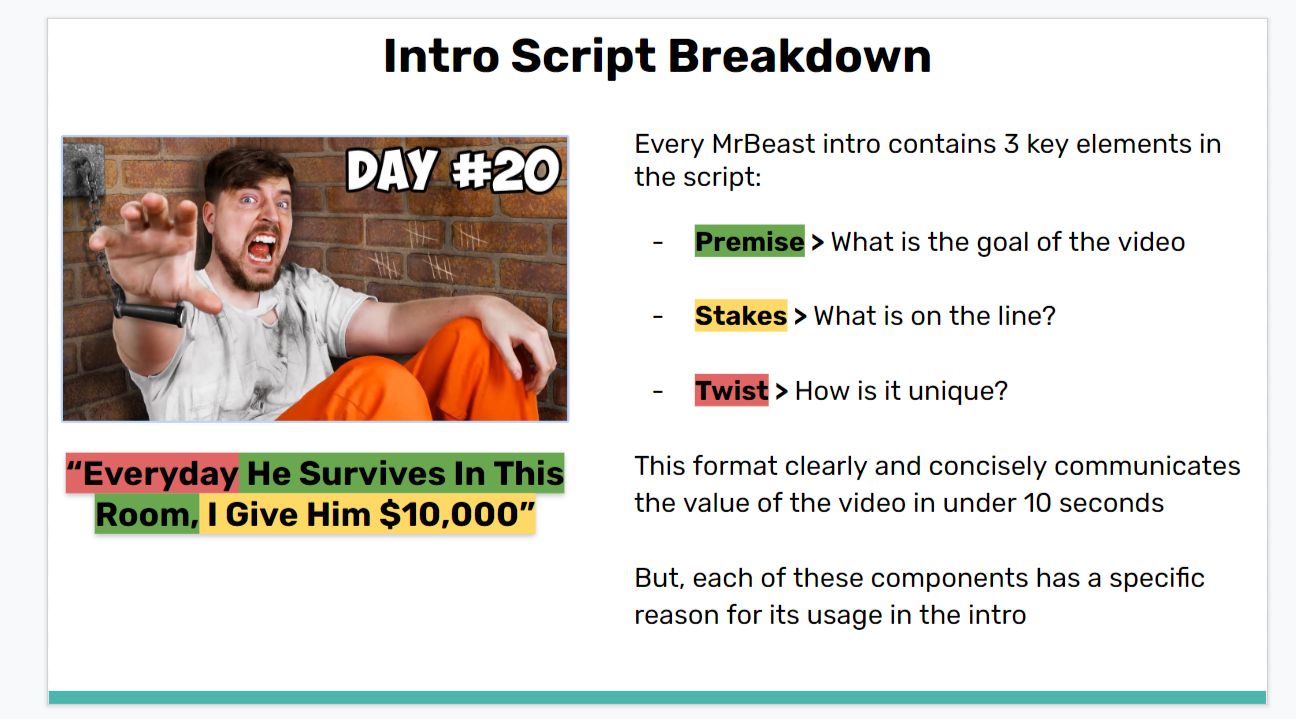

LowKeyJude, a Twitter user who describes themselves as a consultant on YouTube best practices, recently unveiled a deep analysis of Mr Beast's channel, highlighting the professional effort and deliberate psychology that goes into crafting something that seems on its surface like a rich 20-something helping and/or pranking people.

This is a comprehensive breakdown of how MrBeast's videos are targeted, and I found the identification of a 'primal' element to each video intriguing. Videos that touch on notions of survival, or rejection, or what the author describes as "cave-man feelings." For example, the notion of a miracle cure, even if the miracle is only the accessibility and scale.

This is hardly MrBeast's first brush with controversy, and in an odd way this video about blindness has elements of his most successful production to date: A real-life Squid Game with almost half-a-million dollars on the line.

This thing has over 355 million views and, if you've seen Squid Game, the amazing thing is that MrBeast seems to have watched the show without paying any attention whatsoever to the message of it. Squid Game is a story deeply cynical about human nature within a capitalist system, and the games themselves are moments of savage horror. This recreation of it is tapping into the appeal of the show and grappling without ever actually engaging. The irony is sometimes too much.

MrBeast himself says this video was a new style of format but, really, it doesn't stray too far from his standard template beyond being a little less intense due to the heartwarming, or perhaps primal, subject matter. Is MrBeast making a serious subject that might've otherwise been ignored by his millions of young viewers more entertaining? I think both things can simultaneously be true: it's a good outcome that more people will be aware of this particular health issue, but MrBeast doesn't attempt at all to examine the systemic issues of economic inequality and privatized healthcare that create a situation that makes his act of charity necessary.

It's that message, and the shallowness of it, that I think has rubbed some critics the wrong way. MrBeast doesn't say anything about global healthcare or god forbid capitalism (I suppose it's working out quite well for him) in the video, which fundamentally exists to go viral. And there are bits in this video where, quite unintentionally, MrBeast humblebrags about his wealth while being generous. He gifts one of the patients a Tesla and, as it's being driven up, jokes "if [the driver] crashes it I'll just buy another."

In a comment on Twitter, MrBeast comes frustratingly close to recognizing that socialized healthcare would be a path to solving this issue for many more people in the US.

I don’t understand why curable blindness is a thing. Why don’t governments step in and help? Even if you’re thinking purely from a financial standpoint it’s hard to see how they don’t roi on taxes from people being able to work again.January 30, 2023

There are two schools of thought on MrBeast. His fans see him as an incredibly benevolent individual who's equal parts P.T. Barnum and Mother Theresa, using pomp and pizzazz to do great things. Then there are those who see him as an incredibly successful and hard-nosed businessman, a millionaire who spends brand money on performative acts of charity for clout.

Here's what MrBeast thought of the reaction.

Twitter - Rich people should help others with their moneyMe - Okay, I’ll use my money to help people and I promise to give away all my money before I die. Every single penny.Twitter - MrBeast badJanuary 30, 2023

I think it's very likely that MrBeast is acting from sincerely held principles. But with this response, he also glosses over the details that make this video morally complicated. He's not simply "helping people"—he's working with a charity, using their resources, and—as the comments beneath his video make the case—enhancing his reputation in the process.

"It did raise awareness and get tons of people talking," said MrBeast in response to criticism, before going on to make a rather unbelievable claim. "Also what profits? The average MrBeast video lost $1,500,000 last year lol."

As other critics on Twitter have pointed out, the money that MrBeast hands out in these viral videos is not always his own money. He does use it on some occasions, and this seems to be one of them, but the wider business model is based on spending a budget that brands have earmarked for charity, which of course is very helpful for corporate tax exemptions too.

There's no denying that, because of this video, 1,000 peoples' lives are better. All credit to MrBeast. Of course, the real figure is 1,001.

Rich is a games journalist with 15 years' experience, beginning his career on Edge magazine before working for a wide range of outlets, including Ars Technica, Eurogamer, GamesRadar+, Gamespot, the Guardian, IGN, the New Statesman, Polygon, and Vice. He was the editor of Kotaku UK, the UK arm of Kotaku, for three years before joining PC Gamer. He is the author of a Brief History of Video Games, a full history of the medium, which the Midwest Book Review described as "[a] must-read for serious minded game historians and curious video game connoisseurs alike."