The 50 most important PC games of all time

They changed how we make games, how we play games, and they changed us.

Half-Life

Released: November 1998 | Developer: Valve

Why it's important: It redefined our expectations for an FPS overnight, including complex scripted sequences, set-pieces and constant immersion in a world that didn’t just play by its own rules, but taught them. Discrete levels, briefings… after Half-Life, they all felt so old, with poor SiN in particular immediately being punted into the history bin.

There is PC gaming before Half-Life, and PC gaming after Half-Life. Its influence is so huge that this entire feature could be devoted to it and you probably still wouldn’t have covered it all. (Half-Life begat Half-Life 2 which begat Steam which begat…. everything.)

But let’s stick strictly to the topic of first-person shooters, the genre that blew up upon its release in 1998. If you are a younger gamer, it may be hard to imagine just how revolutionary even the simplest things in Half-Life were. Like, for example, the opening cutscene, which famously takes your mute character, Gordon Freeman, on a tram tour through the Black Mesa Research Facility while the credits roll. Half-Life started in-engine and never stopped, thanks to the then-revolutionary use of scripted events that propelled the action forward without ever removing you from the game. It was the first shooter with a completely seamless presentation from beginning to end: No levels, no loading screens, no cutscenes—just one long take from beginning to end.

Half-Life made every other shooter seem dated and last-gen on the day of its release.

And then there was the gameplay. Valve was certainly not the first to incorporate clever puzzle design into a shooter (Bungie actually deserves much of the credit for that with Marathon in 1994), but the sheer inventiveness, variety, and brilliant use of environment that made up those puzzles made it as much of an adventure game as an action game. It was also, at times, terrifying, with the tiniest enemies in the game—the headcrabs—scaring the bejeezus out of you with unexpected flying leaps out of nowhere.

Half-Life made every other shooter seem dated and last-gen on the day of its release, and no shooter released since has ever escaped its shadow or influence. Remarkably, it was Valve’s first game, which is why, before it was released, nobody, including the gaming press, paid it much attention at all, while shooters like Daikatana and Prey were soaking up all the hype.

I remember being wonderfully baffled my first time playing Half-Life. After a long tram ride through a subterranean facility, I was now being brightly greeted by scientists as I passed them in the hallways. I was used to shooters like Duke Nukem 3D, which consisted of shooting, shooting, and more shooting from start to finish, but I'd been playing Half-Life for 20 minutes and all I'd done was commute to work. It was weird, it was wonderful, and the absence of things to shoot made for incredible tension. Something, surely, was going to happen. Why hadn't it happened already?

The biggest gaming news, reviews and hardware deals

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

There's plenty of shooting in Half-Life, of course, but what makes it so important was everything else it contained. Watching hapless scientists being yanked up into the maw of a lurking barnacle wasn't just morbidly entertaining, it was a lesson in how the monster operated. The lack of traditional levels meant there was no real resting point, no feeling of safety or escape, that your progress was one long, unbroken journey. The NPCs who knew you by name gave the silent Gordon Freeman a real identity, and the soldiers who cursed his name over the radio made him feel like a legend.

Like Doom before it, Half-Life helped shape shooters to come by showing us they could be about more than just the shooting. They can tell stories, they can teach by example, they can create a world that feels like it exists beyond the crosshairs of your gun. Half-Life laid out the blueprints that modern shooters are still using today. — Chris Livingston

StarCraft: Brood War

Released: November 1998 | Developer: Blizzard Entertainment, Saffire

Why it's important: Largely established the modern esports scene thanks to its success in Korea, with televised shows and a dedicated government body focused on promoting and regulating it. The world has moved on, but Starcraft: Brood War set the pattern.

I really enjoyed StarCraft: Brood War. I probably played the most in Skirmish Mode, but really the entire game is a great example of individual parts all coming together to make something great.

StarCraft as a whole has fantastic progression, introducing a series of problems and having the player overcome them before moving onto the next problem. Where are the resources? Where am I going to build my base? What’s out there in the map? Where’s the enemy? How am I going to win? All these stages flow easily and naturally from one to the next. It also has excellent asymmetry in its forces, with each side having its distinct feel and tactics, but carefully balanced next to each other. The game wraps all this in a great art style and clever audio design that clearly supports the key gameplay ideas.

Brood War builds on the solid base of StarCraft, preserving all the best parts of the first game and giving you something deeper to think about. — Sid Meier

Starsiege: Tribes

Released: November 1998 | Developer: Dynamix

Why it's important: One of the earliest multiplayer-only games (albeit packed in with mech-game Starsiege, before everyone forgot that existed), with a pioneering approach to class based action, base defense, vehicles and team-play. Also, jetpacks! Everyone loves jetpacks!

You can cover a lot of ground with a jetpack strapped to you.

Tribes carried the multiplayer FPS genre forward much further than it gets credit for. It’s a grandparent to games like PlanetSide 2, which expounded on its idea of bases with generators, shields, vehicle stations, and turrets that can be destroyed and repaired. Evolve recaptured Tribes’ technique of airborne, bounding pursuit. Even little touches, like its ‘VGS’ text command system, remain a well-used tool in multiplayer games. More broadly, Tribes 32-player CTF did the legwork for Team Fortress’ classes and Battlefield’s scale.

Tribes was doing this stuff in ‘98, a full year before the titans of that generation, Unreal Tournament and Quake III. Tribes’ influence will continue to linger as more FPSs embrace the Z-axis (like Call of Duty: Advanced Warfare), retreading the special, see-sawing ballet that Tribes pioneered. The whole exterior area of Tribes’ maps is a series of halfpipes, one big rolling skatepark for you to chase and be chased through. And Tribes’ use of projectile weapons like the Spinfusor paired perfectly with this movement technique. Because these sci-fi guns shoot slowly, when you flick out a disc or lob a gamma-ray green Fusion Mortar over the map, you experience the uncertainty of whether your shot’s going to connect as you watch the projectile travel. It’s an ancient experience that mirrors stuff like three-pointers in basketball, or a hole-in-one in golf.

In a period known for incredibly high skill ceiling FPS games, Dynamix delivered one in which almost every shot (outdoors, anyway) felt like a skill shot and movement was a true discipline. — Evan Lahti

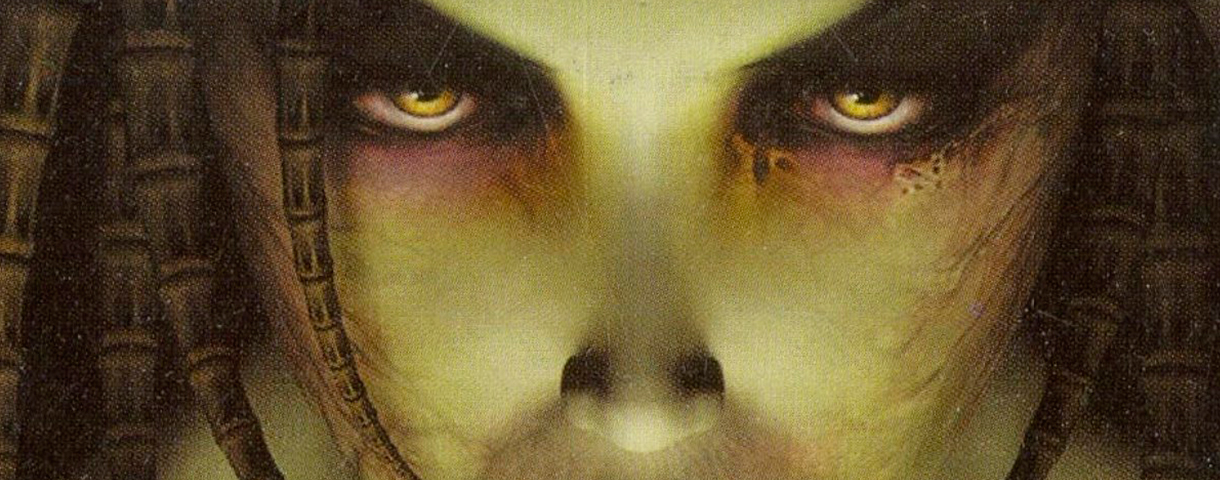

Thief: The Dark Project

Released: November 1998 | Developer: Looking Glass Studios

Why it's important: The first game to truly appreciate stealth and avoiding combat as a mechanic, and a landmark in atmospheric detail and mapping. Its levels felt like real places, with you an unwelcome interloper never far from a savage beating. Yet in giving you a selection of tools for any situation, the power was always yours—not a warrior's power, but a master thief's.

How does one judge the "importance" of a game? Probably most often it's considered some intangible mix of how well-remembered it is, how forward-looking it was, and how much influence it exerted on the games that would follow it. But maybe one much more concrete metric is how often, and how long after its release, a game receives reboots, remakes, rereleases—in other words, commercial attempts to acknowledge that there's still value in that original title, that there's still goodwill kicking around in the public's mind. That people still care.

A reboot says as much about what made the original game great—or at least, what the reboot's creators think made it great—as it does about what's changed in the games industry in the intervening years. And much had changed between the release of Thief: The Dark Project by Looking Glass in 1998, and the release of Thief by Eidos Montreal in 2014. PC gaming, and PC game development, were totally different frontiers in those earlier days, and Looking Glass was forging its own, very unique path in the PC space. The Dark Project, in many ways, cemented all the things that Looking Glass was 'about,' drawing together a number of threads into one, singular experience.

Garrett's movement through the world had the physicality that the studio had pioneered with Ultima Underworld. The City had the foreboding and oppressive atmosphere of Citadel Station, in a Victorian Gothic instead of far-future Cyberpunk setting. The game's mechanics pulled the focus even further away from direct combat than they ever had, and in fact gave the player a ton of systemic tools that encouraged them to succeed at their missions—to inhabit the role of the titular Thief—without spilling any blood at all. And on top of all this was the wry, individualist character of Garrett himself, the voice of the weary outsider to all the City's faction struggles, the lens through which the player discovered this strange and twisted world.

The Dark Project above all trusted its player to find their own way, devise their own successes, to improvise.

Thief (2014) is so important inasmuch as it demonstrates how very different The Dark Project was from everything that came before it, and, despite its undisputed importance and influence, everything that came after, its own reboot included. The Dark Project was a game that above all trusted its player to find their own way, devise their own successes, to improvise. Enormous, sprawling, contiguous levels, packed with side rooms and back hallways, peppered with valuables and documents, all without any sort of minimap to guide you; instead, just a hand-drawn paper map, provided by your informant, or Garrett's reconnaissance, or merely by rumors in the streets of how this grand manor or that pagan lair might be laid out.

One of the most memorable moments in the game happens when, completely lost and disoriented, you check your map, only to find it updated with the phrase "WHERE AM I?" in Garrett's panicked hand, the character just as lost as you are, desperate for a way out. The Dark Project never held your hand—but it did give you the tools, and the trust, to find your own way.

And so 2014's Thief, with its small, constrained levels, myriad fake doors, minimap and mission markers, is so important in that it shows us just why 1998's original stood out, and continues to stand out, as a game unlike other games. Mass market video game technology and design best practices have in many cases trended more toward simplified playable spaces and feature-forward user-friendliness, but it is just The Dark Project's opposition to these principles, its openness and impartiality, that defined it. To attempt to apply today's standards to Garrett and the City is, demonstrably, an exercise at odds with itself—an important lesson to remember. The world of a thief is by no means a friendly or welcoming one; the joy, in the end, is making it through that world on your own. — Steve Gaynor

Baldur's Gate

Released: December 1998 | Developer: Bioware

Why it's important: The RPG that made RPGs mainstream again after several years in the wilderness, and the pattern that they’d follow until Bioware again shook things up with Knights of the Old Republic and Mass Effect. Its Infinity Engine is so beloved that Pillars of Eternity raised $4 million with a promise to be like it, and we’re getting Baldur’s Gate 1.5 next year in Siege of Dragonspear.

“Baldur's Gate brings the AD&D game alive on the computer like no other game before it,” wrote Dave “Zeb” Cook in the intro to the Baldur's Gate manual. He was spot on. There had been plenty of Dungeons & Dragons games before this—many taking place in the Forgotten Realms setting—but none captured the sense of wild, broad adventure, of limitless possibility, or of rich, detailed storytelling. The Infinity Engine let Bioware create a powerful sense of place.

It also spearheaded a push into D&D that would bring forth some of the best RPGs ever made. Black Isle's Planescape: Torment was released a year later, also backed by the Infinity Engine. And Baldur's Gate 2 took everything Bioware had done with the original and made it better.

Through Bioware and Obsidian, Infinity Engine developers would go on to dominate the RPG landscape for over a decade. Neverwinter Nights, Knights of the Old Republic, Dragon Age: Origins and, of course, Pillars of Eternity. Nowadays we've moved beyond D&D, with systems better designed for digital gaming, but Baldur's Gate's richness and texture are still worth striving for. Massive, surprising, and full of wonderful characters, Baldur's Gate was an epic that shaped its genre. — Phil Savage

Wes has been covering games and hardware for more than 10 years, first at tech sites like The Wirecutter and Tested before joining the PC Gamer team in 2014. Wes plays a little bit of everything, but he'll always jump at the chance to cover emulation and Japanese games.

When he's not obsessively optimizing and re-optimizing a tangle of conveyor belts in Satisfactory (it's really becoming a problem), he's probably playing a 20-year-old Final Fantasy or some opaque ASCII roguelike. With a focus on writing and editing features, he seeks out personal stories and in-depth histories from the corners of PC gaming and its niche communities. 50% pizza by volume (deep dish, to be specific).