The 50 most important PC games of all time

They changed how we make games, how we play games, and they changed us.

Wizardry

Released: September 1981 | Developer: Sir-Tech

Why it's important: One of the earliest CRPGs that hinted what the genre was going to be capable of, kickstarting both its own long-running series and helping launch RPGs in Japan. Along with Ultima, it was a huge hit that set the tone for what the games could be, leading directly to the design of games like Dragon Quest.

Wizardry was one of those rare games that captured my imagination utterly. Even though the black-and-white line rendering of the dungeons was oh so primitive compared to today’s 3D games, it nevertheless managed to fully immerse me in its fantasy world. For several long days and late evenings I plunged the depths of the dungeons of the Mad Overlord, the real world around on pause.

How was Wizardry able to pull this off? For one, the world was laid out before you as if it were a place that had its own life and internal logic, to an extent astonishing for that early era of gaming. It felt real, far beyond the surface graphics. Wizardry was also a truly challenging game. It could be unforgiving if you played carelessly: your party of adventures could be wiped out with no ready save point to catch you. But the challenge was fair and rewarded smart play. Something too uncommon with modern games. Finally, the game elements were lovingly crafted and balanced to make a wonderfully cohesive experience.

Wizardry, along with the early Ultimas, had the biggest influence on me as a game designer during that era. They were the shoulders of giants that I and other designers were able to stand on. — Paul Neurath

Pinball Construction Set

Released: 1983 | Developer: Bill Budge

Why it's important: It’s relatively simple by modern standards, but this was one of the first games to bake the idea of making your own content and sharing it with friends into an experience—long before the internet came along to make mods and levels the standard.

The biggest gaming news, reviews and hardware deals

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

Before there were videogames, you darn kids, there was pinball. Back before 1s and 0s took over the world, pinball arcades were where we wasted all our money and time, feeding dimes and quarters into our favorite machines (mine was Captain Fantastic), AC/DC blasting over the speakers, eating Red Vines, and talking about last night’s episode of The Love Boat. Those were the days.

Pinball machines sadly and quickly got shoved to the corners of the arcades once Space Invaders, Pac-Man, and Donkey Kong took over, but in 1983 a genius by the name of Bill Budge created a magical, revolutionary product that brought the pinball experience to our homes and the digital space. But it was more than just that. Pinball Construction Set, made originally for the Apple IIe and Atari 8-bit systems, was the first game that was also a toolset for its users, the direct ancestor of games like Super Mario Maker and Minecraft, that allowed players to make their own virtual machines and share them freely with friends.

Pinball Construction Set was a landmark because it opened up the conversation and language about what a “game” could even be. It taught hundreds of thousands of gamers that creating a game could be just as much fun as playing one. Pinball Construction Set might be a bit more obscure than other games on this list, but is influence cannot be understated. Some of the games you probably love best—maybe even others here—just might possibly have been born in the brain of someone who got their first taste of game design from this remarkable, groundbreaking game. — Jeff Green

King's Quest

Released: May 1984 | Developer: Sierra On-Line

Why it's important: The adventure game truly started here. A full world to explore, animated characters, 3D…the plot and writing and puzzles weren’t up to much, but this was both a creative and technological leap for gaming that demands both attention and respect.

King's Quest opens with an uncomplicated, guileless premise: Bring back three treasures and inherit the kingdom's throne. Simple, right?

Still, in its day, King's Quest: Quest for the Crown was an incredibly sophisticated piece of tech. Originally commissioned by IBM as a showpiece for the upcoming (and ultimately ill-fated) PCjr, the game went on to dazzle audiences with its animated graphics, sprites, and sounds. The box advertised King's Quest I as a "3-D adventure"—which might seem laughable now but, in 1984, no one had ever seen a sprite walk into the foreground before.

It's very much a parser-based game—players have to experiment with typing nouns and verbs into a field to make anything really happen—establishing King's Quest as the missing link between, say, Zork and Maniac Mansion. And as Sierra Online's breakout hit, King's Quest hurled the tiny Oakhurst studio (and the studio's co-founder, designer Roberta Williams) onto the map at last.

In 1984, no one had ever seen a sprite walk into the foreground before.

Maybe the story isn't always 100% compelling, no, but King's Quest introduced the character of young Sir Graham—soon to be King Graham, monarch and hero of the Kingdom of Daventry—for the very first time. (The "Magic Mirror," which recurs as a major plot point in multiple King's Quest games, also has its origin here.) Apart from its own sequels, King's Quest also led directly to Space Quest (1986) and Leisure Suit Larry (1987), plus the satire Peasant's Quest (2004). The rest of the King's Quest series would continue to push at the narrative and technological envelope, and to terrific acclaim. King's Quest IV: The Perils of Rosella (1988) famously asked "Can a computer game make you cry?" (In my case, yes.) As for King's Quest VI: Heir Today, Gone Tomorrow (1992), someone named Peter Spear was quoted right on the box of the CD-ROM (1993) version: "The era of CD gaming is upon us." He knew it before the rest of us did.

King Graham himself would go on to star in a sequel, King's Quest II: Romancing the Throne, as well as the fifth installment, Absence Makes the Heart Go Yonder. In 2015, Graham starred again in an entirely new series of King's Quest games, this time designed by The Odd Gentlemen. It's clear that—if sales, critical acclaim, and longevity have anything to do with it—the Royal Family of Daventry is indeed the "First Family" of computer gaming. It's a dynasty. — Jenn Frank

Ultima IV

Released: September 1985 | Developer: Origin Systems

Why it's important: Morality systems largely started here, an RPG focused not on killing baddies (at least, not as a major goal), but proving yourself worthy of being seen as a hero—the Avatar of the Eight Virtues, there to show both our world and Britannia what they could become.

I first played Dungeons & Dragons in 1978.

The experience was literally life-changing. The experience of telling stories with my friends, instead of being told a story by a storyteller was mind-blowing, unlike anything I’d ever experienced. After that, my life was all about two things: movies and gaming. I’d play just about anything—RPGs, boardgames, you name it. And then came console and computer games. It started with TRS-80s and Atari 800s, Atari 2600s and Colecovisions and then, along came IBM PCs and clones.

On all of those, my favorite games were what passed back then for roleplaying games. And “passed for” is the only way to describe them. It seemed like every game featured some variation of D&D’s characteristics—Strength, Dexterity, Constitution, Intelligence, Wisdom, Charisma, increased by earning experience points. They all seemed to feature the traditional character classes—Fighter, Mage, Paladin and so on—with the possibilities and limitations established in tabletop RPGs. There were various character alignments and gameplay driven by dierolls, just like D&D. And the stories? Well, most of them were sort of like Monty Haul dungeon crawls (my least favorite thing to do in RPGs). You move down a corridor (avoid the traps!), open a door, enter a room, kill the monster inside, steal the treasure it was guarding. Wash, rinse, repeat. End of “story.”

In other words, those early computer roleplaying games weren’t so much about 'roleplaying' as much as they were about 'rollplaying.' I played them but, in retrospect, I’m not sure why. There wasn’t much originality or creativity in them. And the stories were pretty lame. (Here I’m being generous.)

Then, around 1985, Ultima IV appeared, not exactly out of nowhere, but certainly like a bolt from the blue that changed everything for me. This was no dungeon crawl—this was a philosophical journey, a quest not for glory and riches or a quest to defeat the Evil Bad Guy threatening the world with… well… something bad, but a parable on the strengths made possible and the limitations imposed by ethical behavior.

It wasn't Frodo or Conan in the world of Britannia—it was you.

You knew something was different from the moment the game started. There were no dierolls to determine your character’s nature and capabilities. There was a gypsy who posed questions for which there were no right or wrong answers, only each player’s views on right and wrong behavior. Character creation wasn’t about fantasy fulfillment, but about creating an idealized version of yourself. It wasn’t Frodo or Conan in the world of Britannia—it was you.

And the quest itself? No villainous badguy or meaningless dungeon crawl here (well, at least until the end), but a journey through the land of Britannia whose purpose was to master the foundations of Truth, Love and Courage, as expressed through the eight virtues—Honesty, Compassion, Valor, Justice, Sacrifice, Honor, Spirituality and Humility.

Notice that none of these would do you any good in a dungeon or on a battlefield. You were on a quest to perfect yourself, to become a paragon of virtue—in other words, the Avatar. And in so doing, two things would happen. First, you would be an inspiration to the people of Britannia. Second, you—the player—would learn something about yourself and about the world. The real world.

Consider mind blown.

I could recount the details of the story—well, actually, I couldn’t since I don’t remember it all that well—but Ultima IV’s story, while better than any other non-Infocom game I’d played to that point… the story was so not the point.

The feeling the game gave me. That’s the point. It came as close as any game had to the point to making me feel like I was in a real roleplaying experience. The kind I’d had with my friends back in 1978. That was enough in and of itself, but it was also the first thing that lit a fire under my butt to move from tabletop games to computer game development. And that fire had a purpose—to give people the experience of telling stories with their friends (well, with me, anyway). Together. Sharing authorship as well as adventure and derring do.

That’s all I’ve wanted to do for the last 32 years. Recreate D&D. And it all started with Ultima IV. Thanks Lord British, for everything. — Warren Spector

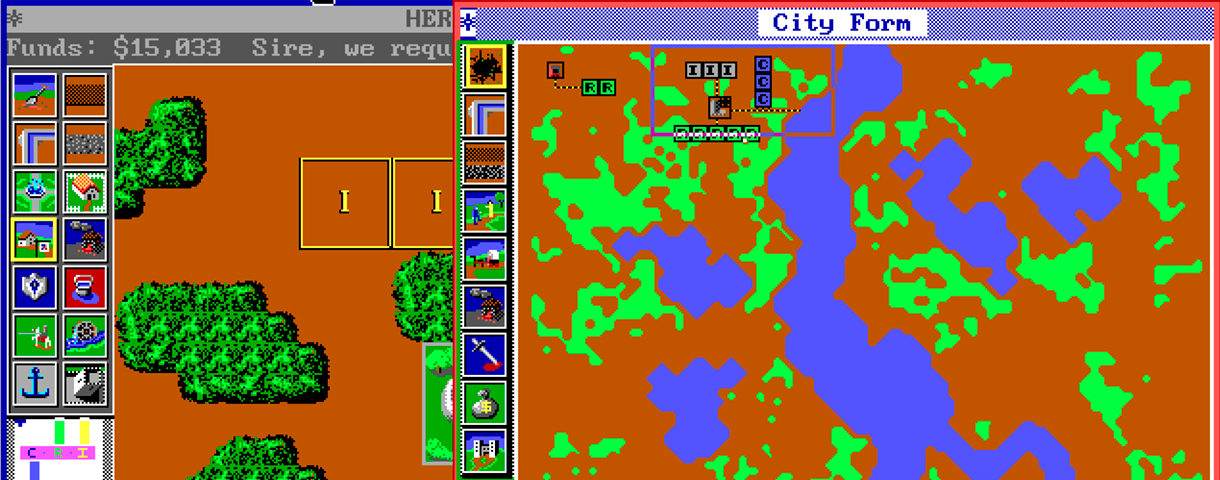

SimCity

Released: February 1989 | Developer: Maxis

Why it's important: The first city building game, and a staggering jump forward for simulations. Primitive as it looks by today’s standards, you could look down and feel like you’d created a living, breathing world just by splashing out some zones. And then have Godzilla stomp it.

When Will Wright, the designer of 1989’s SimCity, talks to us, I imagine he feels how we feel when we talk to our dogs. He is operating at such a higher level of intelligence that he must carefully limit his vocabulary to the few commands we understand, before handing us a biscuit.

SimCity was his first biscuit to us. (Or second, if you include the also quite entertaining but more obscure Raid on Bungeling Bay in 1984). As with Bill Budge’s Pinball Construction Set, SimCity understood that giving players creation tools can be just as much fun, if not moreso, than simply playing a formal game with a beginning, middle and end. (In fact, because SimCity had no “win condition,” but could simply go on forever, Wright originally had trouble convincing anyone to publish it.) SimCity was truly educational as it entertained, turning us all into urban planners and civil engineers with utterly engrossing gameplay that made us think about zoning and taxes and power grids in a way that was as rewarding as shooting aliens, Nazis, and Nazi aliens.

It was also the beginning, though no one knew it at the time, of a computer gaming dynasty. SimCity went on to spawn a host of memorable Sim titles, some better than others (we’ll just pretend Streets of SimCity never happened), culminating in the one that came to be one of the most popular games of all time: SimCopter. (Just kidding. We mean The Sims of course.) And every building game and franchise since, such as Rollercoaster Tycoon, owes its existence entirely to SimCity.

But SimCity was the first, and it still endures. It was the game that taught us that winning wasn’t everything—but fixing traffic jams is. — Jeff Green

Wes has been covering games and hardware for more than 10 years, first at tech sites like The Wirecutter and Tested before joining the PC Gamer team in 2014. Wes plays a little bit of everything, but he'll always jump at the chance to cover emulation and Japanese games.

When he's not obsessively optimizing and re-optimizing a tangle of conveyor belts in Satisfactory (it's really becoming a problem), he's probably playing a 20-year-old Final Fantasy or some opaque ASCII roguelike. With a focus on writing and editing features, he seeks out personal stories and in-depth histories from the corners of PC gaming and its niche communities. 50% pizza by volume (deep dish, to be specific).