The original Mafia's period detail is what makes the most impact today

Sam Roberts dons his finest pinstripe suit and revisits the city of lost heaven.

Reinstall invites you to join us in revisiting classics of PC gaming days gone by. This time, Sam Roberts revisits Mafia: City of Lost Heaven.

The first Mafia games share one thing that I'd totally forgotten until I reinstalled the original: they both challenge you with mundane tasks before the fun kicks in. In Mafia 2, you stack crates in a van for as long as you can stand it. In City of Lost Heaven, you go through five horrendous taxi fares in Tommy Angelo's pathetically slow car before you sack it off and enter a world of organised crime.

In both cases, boring tasks play a narrative role, and for all the ways Mafia borrows from popular movies for the sake of tone, that portrayal of your slow ascent through the mob is unique to Lost Heaven. You feel small-time. It's deferred gratification until you finally get a gun in your hands, over an hour into the story. While Mafia 2 doesn't round off the tale of its protagonist to a satisfying degree, Mafia charts the complete story of Tommy Angelo's rise and eventual fall at the hands of his dangerous new employers.

Mafia arrived on PC just a few months after GTA 3. In a genre as new as the open-world game was at the time, comparisons were inevitable but irrelevant. They weren't competing; they used the open-world idea in such opposing ways it's obvious neither team of developers was conscious of what the other was doing. GTA 3 is all about creating and experimenting with chaos. Mafia is a linear action game enriched by the atmosphere and period detail of an open world—cop shootouts and exploration clearly placed as secondary pursuits to the main story.

The city of Lost Heaven, a ludicrously melodramatic monicker for what is a red-tinted amalgamation of San Francisco and New York, is built to a standard we now expect from sandbox games. A ship sails under a drawbridge that opens while I patiently wait in traffic. The score changes dynamically as I enter Chinatown. In Salieri's bar, Mafia's hub, the interior detail is extraordinary, loaded with props and furniture and elevated by the background chatter of its patrons.

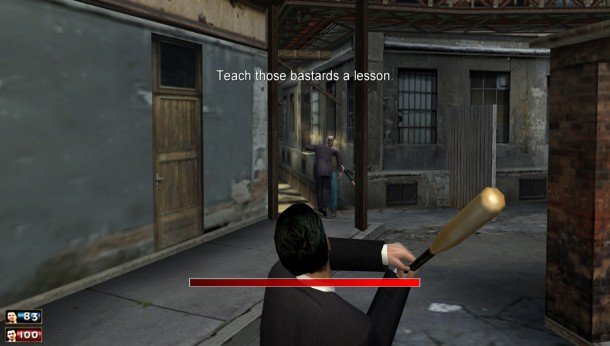

I remember Mafia as a boundary-pushing, realistic-looking Goodfellas-a-like, and that's because my memory has been nostalgically caressed with Vaseline. It's a very blocky world, for all its detail, and while the character models are mostly sharp, the animation is slightly too close to Team America territory to not find it funny when Tommy Angelo climbs into bed with love interest Sarah. This is easily forgiven, however: if the visuals have been technically outstretched, the art direction keeps Mafia from ageing sourly.

The driving is a little harder to forgive. When I accelerate down a slope in Mafia, I'm as much in control as I am riding down a hill on a piece of sheet metal. It's a furious, random experience that will always end in awkward disaster or mild relief. My role in the whole affair is minimal. I assume Mafia's cars are simply faithful to the '30s setting, and that is why their ability to accelerate is so inadequate as to stretch the term 'car chase' to its limit. Some of these cars are so slow that a slightly steep slope can lose you the mission. It's both funny and a bit annoying, like a car version of the two old men fighting amid a kingdom of dogs in Pixar's Up.

The difficulty of the driving is only amusing until you reach the notorious racetrack mission. For those not familiar with this part of the story, it's set up by the bizarre premise that first-time race driver Tommy has to win to protect Don Salieri's gambling scam. Anything but first place isn't good enough. Back in the day, this early mission was so hard it prevented many players from ever seeing the majority of Mafia's story, so inhumanly fast were its AI drivers.

The biggest gaming news, reviews and hardware deals

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

In the patched version the difficulty of this racing sequence has been solved, but imperfectly. You can adjust it so the usually aggressive drivers politely move aside and slow down if there's any threat of you not winning, and you can turn off the sensitive damage. Now it's too easy. In 2002 I felt like the developers had suddenly turned on me.

For this writeup I tried to beat it on 'extreme' difficulty six times, and found it laughably tough to even approach first place. Remembering how close I came to punching my dad's computer 12 years ago, I ended up coasting it on the easiest difficulty.

While the shooting is probably as out of date as the driving, I think it remains entertaining to me because I'm so tired of the cover system being the only solution to the logic issues of third-person combat. In Mafia, you make your own cover behind doorways and corridors, and given that you're only about as tough as the enemies you're fighting, each venture into open territory feels like a Wild West duel. It's slightly too hard and poorly checkpointed, but the feeling of chance and aggression is often more exciting than the blind shooting from cover that pervades today's games.

I didn't expect Mafia's driving and combat to remain timeless, and they were never the parts I appreciated most about the game anyway. It was the period detail and the story that had such an impact on my younger self. This, to me, is how organised crime should be portrayed: a seemingly exciting escape from a mundane life for Tommy Angelo that ultimately eats away at him, and that cannot itself be escaped. Mafia borrows liberally from Goodfellas and The Godfather in telling this story, but it deserves to be credited as one of gaming's first great period pieces.