L.A. Noire: The VR Case Files shows that VR needs to focus on humans

An uncanny experience in a virtual shoe shop.

Three years ago, with the commercial release of VR headsets looming on the horizon, it was possible to imagine that the world was about to change. And it was about to change, but not in the way that I had imagined. Virtual reality hasn’t had the impact I’d hoped, in other words. No one I know owns a headset, and it hasn’t even caused a moral panic in the mainstream press, which is the true indication that something has arrived.

I’m not cynical about the current state of VR or its software. I think we’re doing ok. I understand baby steps, I understand how risk averse most publishers and developers need to be, and how foolhardy it would be to pour millions into VR development this early in its life. It all makes sense, but that can’t snuff the disappointment I feel in VR’s general lack of presence, its seeming inability to make me forget that I’m wearing a headset, and the industry’s focus on bite-sized experiences that serve as gentle tourist-like excursions rather than, say, an alternate life visited.

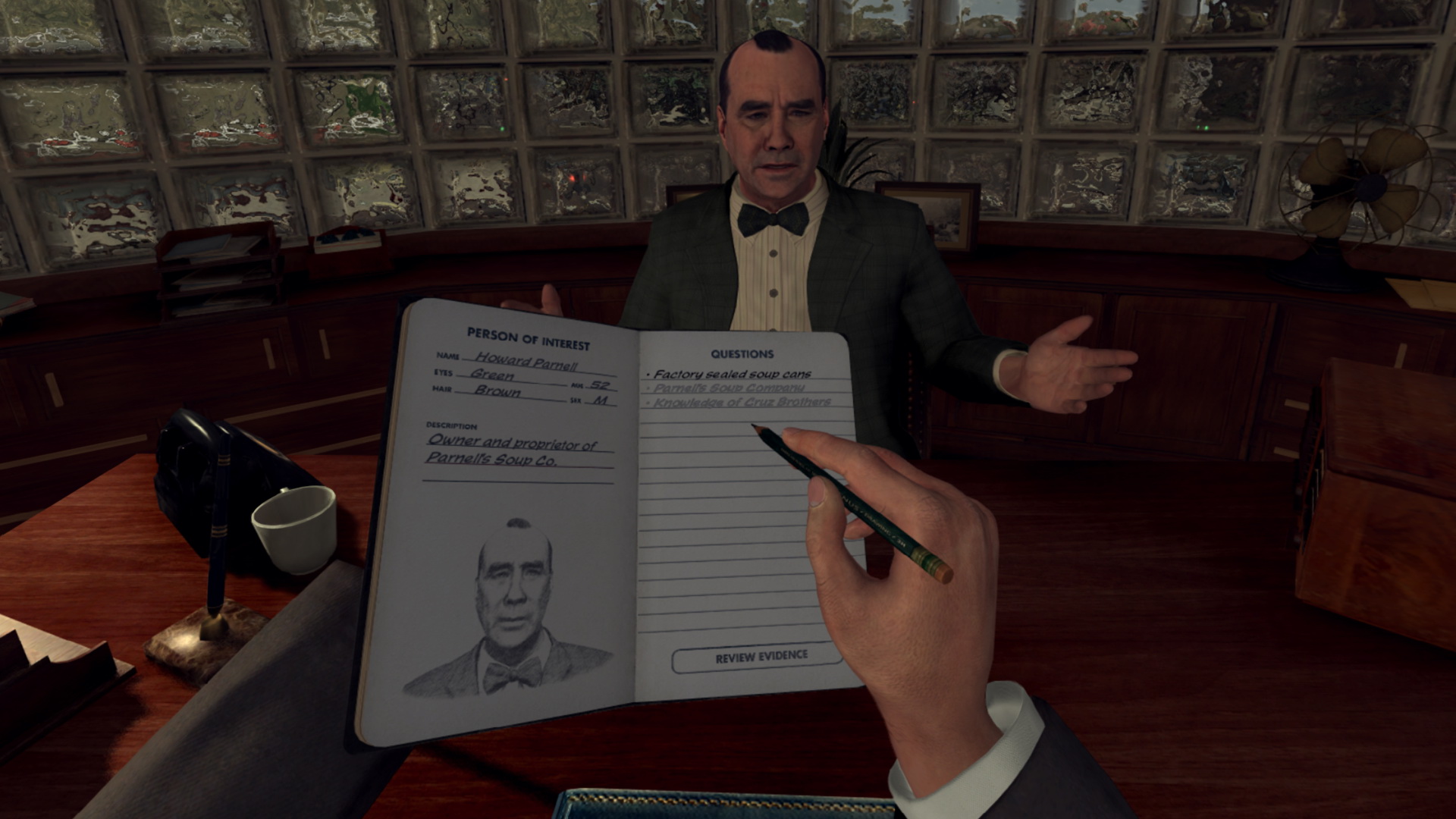

L.A. Noire: The VR Case Files isn’t going to change much about that last point: it is, after all, a condensed version of the original game collecting seven missions (or case files) best suited to VR. And yet, it’s easily the most impressive, nay startling, VR experience I’ve had since playing Eve Valkyrie for the first time. It wasn’t because 1940s L.A. was especially impressive, nor was it because punching people in the face with Vive’s motion controllers was cathartic (though it was!). The reason The VR Case Files is amazing is because of the people.

I played the mission Buyer Beware, which has uppity cop Cole Phelps investigating a murder at a shoe shop. Tim gives a blow-by-blow of how this mission plays out in VR, and it’s engaging enough to investigate the sidewalk murder. But everything changed, for me at least, when I entered the shoe shop to speak to Clovis Galletta, the seemingly shifty store clerk.

I felt like I was standing next to a person, whereas NPCs in VR can often seem either too small or too large, or else too wooden.

This was my first encounter with L.A. Noire’s revamped interrogation system, but whether I should act the bad cop or the good cop weren’t huge concerns for me. Instead, my first thought when listening to Galletta speak was this: am I standing too close to her? (If it was real life, I definitely was). Am I invading her personal space? I immediately stepped back and waited for her to react to my body language—an instinctual, barely registered action that we all probably carry out in real life occasionally. But Galletta didn’t respond of course, because she’s a character in a video game.

As she spoke, it felt pertinent to monitor both her face and her body language, in the way we do with real people. And that’s the nugget of L.A. Noire’s interrogation system of course, but the fact that it worked so well startled me. I had momentarily behaved like I would in front of a human, and I’ve never done that in VR before.

The reason it’s so effective in L.A. Noire is due to MotionScan, the motion capture tech used (exclusively, at this stage) in the original game. Galletta’s face was nuanced, her movements subtle and human-like, and most importantly: her dimensions, her height, her width, all felt right. I felt like I was standing next to a person, whereas NPCs in VR can often seem either too small or too large, or else too wooden.

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

Maybe this is the kind of experience that VR should chase right now. Instead of virtual Pong or horde mode shooters or racing games, perhaps the element that will win people over are the subtle ones that make virtual worlds feel like real ones. VR software doesn’t need to be realistic, but I think most newcomers want to feel shaken. They want to feel as if they’ve stepped into another world. And what I learned from L.A. Noire is that perhaps the best way to do this is to focus on people, life, conversations. I'm usually one to race through dialogue in games: I like driving, and shooting. But in L.A. Noire, I longed for every human encounter.

We all knew VR would need to establish its own styles and genres—that what we play on screens couldn’t possibly make a direct leap over—but how many studios are doing this? The VR Case Files arguably isn’t innovative, but it contains the kernel of something VR can do that, crucially, makes for an experience you can't get on a TV.

Of course, The VR Case Files is a game, and like most VR games it can’t hope to maintain this illusion of reality. Movement is great as far as VR games go, but overall, movement isn’t great in any VR game. Meanwhile, VR’s grainy resolution has a long way to go too, as do efforts to eradicate motion sickness. At the moment, the best we can hope for when donning a headset is that we’ll feel, at least occasionally, that dreamlike sensation of being somewhere else. And by leveraging tech designed to make humans more lifelike, The VR Case Files delivers one of the most effective examples of it yet.

Shaun Prescott is the Australian editor of PC Gamer. With over ten years experience covering the games industry, his work has appeared on GamesRadar+, TechRadar, The Guardian, PLAY Magazine, the Sydney Morning Herald, and more. Specific interests include indie games, obscure Metroidvanias, speedrunning, experimental games and FPSs. He thinks Lulu by Metallica and Lou Reed is an all-time classic that will receive its due critical reappraisal one day.