HDR's promise is stunted by reluctant developer support

We speak to game developers and hardware manufacturers about the emerging color standard.

When a potential new tech standard emerges from the wilds, we always hear about it first from the manufacturers selling it to us. The problem with that is obvious: it can be hard to tell if this new technology is good for us, or simply good for selling something to us. Sometimes it’s obvious, of course: new graphics card, new lines on a graph higher than the last. HD and 4K had the benefit of understandable and tantalising numbers, too: everyone understood that 1080p was the magic figure that would unlock newfound image clarity, and that 4K is quantifiably better again. But what about HDR?

A quiet revolution in color reproduction has been simmering for decades, and it's finally reaching the beginnings of mainstream adoption. HDR is an easy sell at the most basic level. As PC gamers, we’ve had an eye on brightness and contrast values for years now when we shop for a new panel. But High Dynamic Range itself is something more standardised than that, and much more complicated than "better colors." At the time of writing, seven different standards are vying for dominance—HDR10, HDR10+, Dolby Vision, HLG, PQ, SL-HDR1 and Advanced HDR—and to read each standard’s definition is to stare into the eye of the universe’s infinite complexity.

We’ve broken down what HDR actually is for you already, but there’s one question that remains unanswered: is it actually worth it? Does HDR really make our games and movies better?

HDR by the numbers

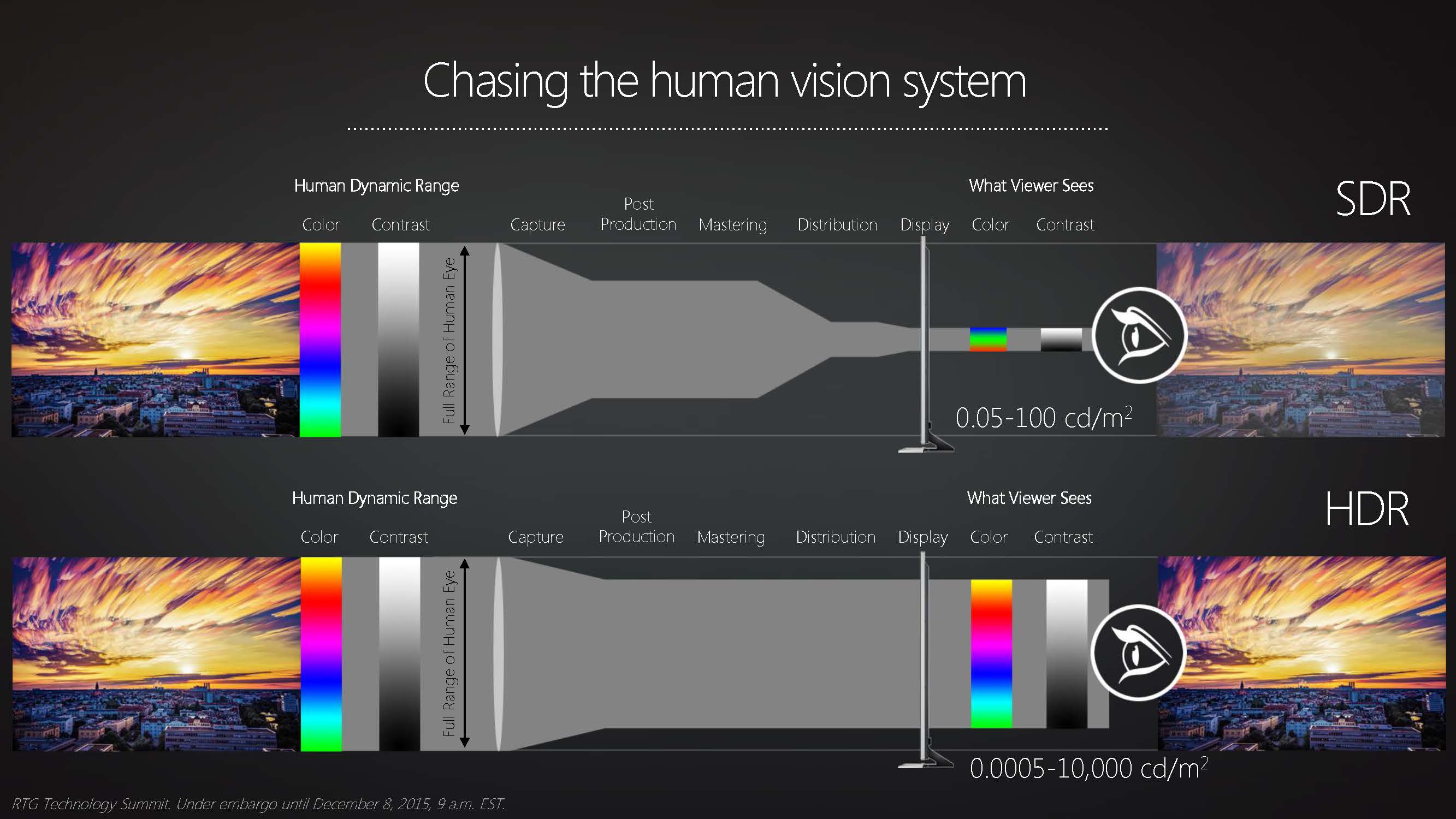

Generally the consensus is "yes: HDR does look better," based on the viewing experience alone. But quantifying that is tricky. Most of the information you’ll find that attempts to do so uses side-by-side comparisons to demonstrate the visible improvement in color reproduction HDR has in its locker. The problem is that you’re probably looking at that image on an SDR screen. This means rather than comparing HDR to SDR, you’re comparing two SDR images, and that’s not going to enlighten anyone. So unless you’re physically evaluating two different panels, the best way to judge HDR’s benefits is with numbers.

The two big stats that best indicate HDR's leap forwards are in its 10-bit color depth and 90 percent coverage of the DCI-P3 color space. To unpack those for a moment, bit depth of colors refers to how many bits are used to indicate the color of one pixel. The most common current standard is 8-bit color. With RGB displays, that adds up to 24 bits of color, or 16.77 million unique colors. With HDR's two extra bits per pixel, that gives 30 bits of color, or a color palette of 1.07 billion colors. HDR is able to better articulate a more precise color to display, because it has more data to do so.

The unfriendly-sounding DCI-P3, on the other hand, is a gamut of color devised by the film industry. It encompasses the sRGB and Adobe RGB color spaces, and the more of the color space a panel can cover, the better. HDR screens need to be able to reproduce 90 percent of the DCI-P3 color space as a minimum (this is known as wide color gamut), although the emerging Rec. 2020 HDR standard comfortably exceeds it.

Color spaces can be a bit abstract when you’re trying to figure out whether your monitor is obsolete, so the benefit is best illustrated by images like this, which shows how much further HDR goes than the paltry range of colors we’ve been putting up with like schmucks all these years.

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

These numbers can’t substitute the experience of doing a side-by-side comparison in person, but they do at least tell us that HDR is a real thing built on new technology rather than empty marketing. The data quantifies that the difference between HDR and the old standard is visible.

Things might be relatively straightforward for us as consumers—spec sheets swelling with numbers and acronyms notwithstanding—but that’s not to say it’s straightforward for game and engine developers to actually implement. We reached out to Nvidia, whose research teams have been working with HDR for years, to find out what’s actually involved in the process.

HDR and game development

Nvidia tells us that it’s relatively simple, since most games already render in FP16 (a floating point HDR rendering calculation) and tonemap back down to standard dynamic range. Internally, games are already rendering in HDR, basically using 64 bits per pixel (16-bit floating point for RGB plus alpha) and then mapping that to the 32 bits per pixel (8-bit integer RGB plus alpha) output of most current displays. So as you sometimes hear from particularly candid console game devs, implementing HDR is more a matter of not downscaling the dynamic range, rather than specifically working upwards.

Unreal Engine 4 and Unity already let developers generate HDR output, but the developers themselves first need to generate the HDR assets. To support HDR, they’ll also need to adopt physically-based shading: a physics-based simulation (2K’s Naty Hoffman explains this in-depth if you’re interested) of how light behaves with different materials. Working in this way is already a major trend, according to Nvidia's spokesperson, which has only recently become possible in real-time graphics. Developers can use the ACES (Academy Color Encoding System) pipeline developed by Hollywood’s CGI masterminds as a reference tone mapper for HDR.

In other words, rendering out in HDR isn’t the tricky part—working towards that goal with all your assets from the beginning of the project is.

Enter Julien Bouvrais, Eidos Montréal’s chief technology officer. He and the studio already have an HDR-ready game under their belts with Deus Ex: Mankind Divided. "It’s not necessarily about putting in more work," he says. "It is however about making sure that you tune your game with HDR in mind."

Eidos Montréal moved from the industry standard 8 bits per channel to 16 bits with their rendering engine "even before HDR was a thing for the consumer," he continues, saying the studio was spurred on by the advent of physically-based rendering. "For the sake of precision, we invested in wider storage for colors. When rendering in non-HDR, we would then use a tone mapping filter to convert the image to a narrower color gamut." Again, the choice of whether to tonemap down to SDR, rather than work up to that fabled HDR standard.

But Bouvrais agrees that the real work comes from authoring assets with HDR in mind from the start. Since it’s still relatively new in gaming, Eidos Montréal had to use a lot of workarounds to get past this problem and achieve true HDR. To Bouvrais, it’s definitely worth it: "We end up with very impressive environments when rendered on good HDR displays. It really showcases what HDR can do."

Timothée Raulin and Mathias Grégoire, the lead 3D programmer and lead 3D artist at Endless Space developer Amplitude Studios, tell us there are several costs to consider when implementing it, too.

"HDR is an incredible tool you can use to increase the player’s immersion," says Raulin, "but it’s also very expensive in terms of resources—human and graphics." Firstly the team needs to learn how to properly exploit it, and then has to wrestle with the resource cost of "heavier and more numerous textures inputs, lots of light and reflecion probes, longer build times."

HDR is an incredible tool you can use to increase the player’s immersion, but it’s also very expensive in terms of resources—human and graphics.

Timothée Raulin, Amplitude Studios

"We need to adapt the production to anything related to lighting, skyboxes, and material rendering," says Raulin. "Then, we also need to take some time to produce and tweak those, but it’s a choice you have to make, and it’s also more about what you actually want to achieve with your game."

The motivation to work with HDR in mind from a game’s pre-production onward will increase as adoption numbers grow and we all sit, ready and salivating, before our HDR-ready monitors. But while triple-A studios like Eidos Montréal and the Sega-backed Amplitude will always be in a position to contemplate new fidelity standards, the conversation must be slightly different for smaller indie teams and one-person studios. Sure, the commercial game engines support HDR output, but can developers working to tight budgets afford the human and resource-based costs Raulin mentioned?

Jake Anderson is in just such a position. His indie multiplayer shooter Cavern Crumblers recently launched on Steam. "Maybe HDR will soon be the standard in triple-A games," he tells us, "and maybe even in the mid-size games. But I don't think it will be the standard for indies, at least not anytime too soon."

While Anderson hasn’t been working with HDR in mind, his experiences with working in different engines are that the ease of implementing it does vary from engine to engine. Since cost/benefit analysis is paramount in indie development, he says, the decision to pursue HDR depends on your game. 3D open world RPG? Sure, it might add that extra layer of immersion and make all the difference. 2D platformer? Not so much.

Will HDR screens catch on?

The burden of responsibility doesn’t lie with developers to make HDR happen, though. It lies with manufacturers themselves. Carlos Angulo is senior product marketing manager at Vizio, which has several HDR TVs already on the market.

"3D came and left because no one wants to wear the glasses," he tells us, "and 4K is great but it’s a natural progression that enhances the detail. But for most consumers sitting in their living room who are 10 feet from their TV, it might be difficult to discern the difference. High dynamic range brings a picture quality difference that viewers can see, and we’ve focused on showing what that difference is in terms of color and contrast and depth."

It’s an important point. One of HDR’s strongest facets, particularly in a gaming context, is that when we ask ourselves if it’s worth it, we’re only really talking about the financial worth, rather than the cost of time and effort. VR, for example, costs money, but it also demands you ensconce yourself in a headset that probably isn’t quite there yet in terms of acceptable comfort levels for long sessions. HDR is an entirely different proposition: invest in it and it’s yours to enjoy in just the same way you were enjoying games before.

3D came and left because no one wants to wear the glasses. High dynamic range brings a picture quality difference that viewers can see.

Carlos Angulo, Vizio

What’s less clear—until you stand before an HDR panel yourself—is how transformative that experience actually is. Vizio’s senior director of product management John Hwang offers some insight, explaining that not all HDR panels are created equal.

"These are really the three largest things when it comes to the display," he says. "What is the contrast/dynamic range capability? What is the color gamut of that display? And how are they tonemapping down?" The answer will vary hugely, depending on the individual model.

For Vizio’s own evaluations, they run side-by-side comparisons in the lab using SDR panels, one modified at a firmware level to be able to read and implement the standard that HDR content is encoded in, and another left untouched. There was a clear difference between the two panels, Hwang tells us, just by virtue of the HDR encoding alone. "Basically that’s because HDR content is 10-bit, SDR is 8-bit. So even in standard SDR TVs today, those panels exceed the capabilities of regular SDR." Basically, HDR’s bit depth advantage gives it the edge in raw information terms, even before hardware capabilities come into play.

That seems a good indicator of HDR’s transformative powers. But it’s also an indicator that there’s a broad gamut of quality within all products bearing those three letters. If that’s the very bottom end of HDR, the ceiling is certainly high enough to house a niche enthusiast market even if and when HDR becomes as ubiquitous as HD. Hwang breaks down how the manufacturing costs mount up as you go from bottom end to that enthusiast market: "If you’re looking at the maximum capabilities of what HDR10 is, which is 1000 nits, compared to a run-of-the-mill HDTV which was designed for SDR and has 250-300 nits, that’s a pretty significant cost-up."

Focusing purely on panel brightness, he explains, more zones of local dimming need to be added, which enables independent zones to go from deeper blacks to higher brightness. Then there’s color reproduction. "There are technologies like quantum dot that allow you to get really close to the maximum capacity of HDR10 or Dolby Vision color reproduction," he says. All of this adds more onto the price tag, with a ladder of less expensive tech such as LED phosphor beneath the top end, which creates a consumer marketplace with a pretty broad range of products, all bearing the HDR name.

Answering the central question—whether HDR is worth it—from this standpoint is, as ever with bleeding edge tech, dependent on how much money you’re investing in it. The principle of diminishing returns holds fairly true throughout PC gaming, whether it’s that second GTX 1080 Ti or a case with its own concierge—and it seems just as true of HDR.

There are a few dominoes lined up when it comes to HDR, then. The first to topple is a change in approach from studios, and we’re already seeing some like Eidos Montréal blazing that trail. The more that follow suit, the sounder your investment in the tech will feel. Greater numbers of panels, at differing price points, will help answer that nagging voice that enters your head whenever you place an item in the online basket, too. Unlike VR, the financial barrier for entry isn’t especially high here—let’s not get into whether Google Cardboard is a viable option—so the risk of backing another stereoscopic 3D is diminished.

There’s one other aspect to HDR though that no one we reached out to had a clear answer to: does it offer any new gameplay opportunities? When HD came along, it changed games not just in their appearance but in their design. With the newfound fidelity it brought to developers like Irrational Games came an opportunity to tell a game’s story through the environment. Suddenly you could read the posters on the walls, the labels on the items in the refrigerator, and the writing on the bad guy’s tattoos. More than just a new fidelity standard, HD ushered in new experiences in games.

HDR, on the other hand, can only really claim to enhance the sense of immersion we already get from games now. That’s not necessarily a bad thing, of course, but something to consider before going from basket to checkout.

At the end of the day, at least for now, the idea that HDR will totally change the way we see games is a stretch. We had monitors in 1995 that were capable of 1600x1200 resolution and costed $500. They worked very well, and not a single 3D game could even run at 1600x1200 at with good frame rates for years. Heck, 3dfx’s Voodoo and Voodoo 2 didn’t even support more than 800x600 and 1024x768, respectively! What helped games wasn’t the advent of HD resolutions, which had been around for more than a decade, but rather the availability of hardware that had sufficient performance and memory to hold higher resolution textures. Graphics processors—before they were called GPUs—also introduced new features that allowed more realistic graphics.

Graphics in games vary wildly, and depending on the games you play, HDR makes little to no difference in the overall experience. HDR shows its advantages in games that focus on realistic graphics, but many games lean towards stylized artwork where HDR plays no pivotal role.

HDR is more like going from 16-bit color to 24-bit color, or if you want to stretch things, going from 8-bit color with a 24-bit palette to full 24-bit color. But 24-bit to 30-bit isn’t a massive revolution. HDR’s biggest selling point is the use of numerous backlights that allow zoned lighting, so blacks can be close to 0 and whites can be close to 500 or 1000 nits. But 1000 nits white is painful to look at! Better backlighting technology—like OLED—is more tangible.

Phil 'the face' Iwaniuk used to work in magazines. Now he wanders the earth, stopping passers-by to tell them about PC games he remembers from 1998 until their polite smiles turn cold. He also makes ads. Veteran hardware smasher and game botherer of PC Format, Official PlayStation Magazine, PCGamesN, Guardian, Eurogamer, IGN, VG247, and What Gramophone? He won an award once, but he doesn't like to go on about it.

You can get rid of 'the face' bit if you like.

No -Ed.