Were you surprised that there was such a positive response to the game?

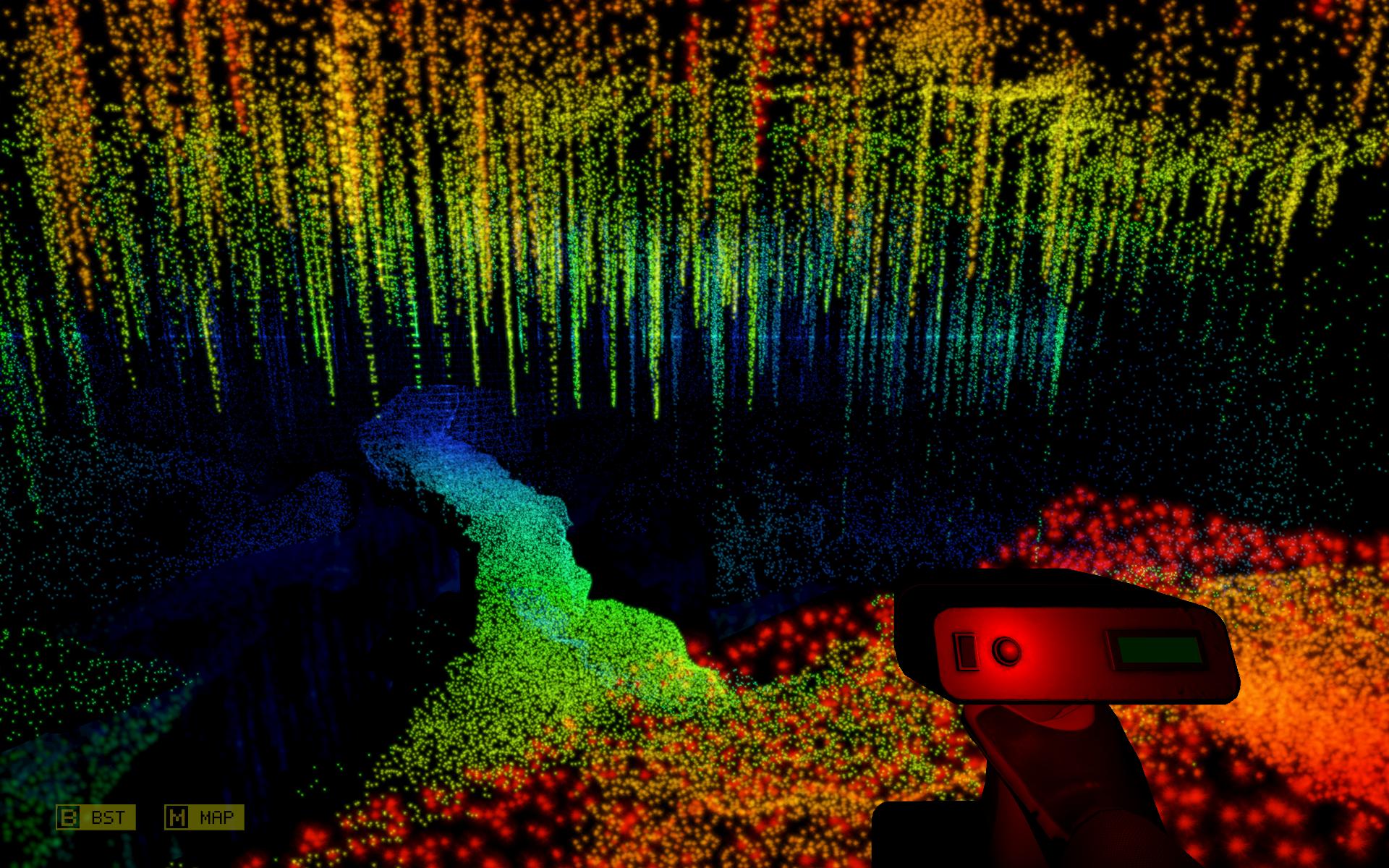

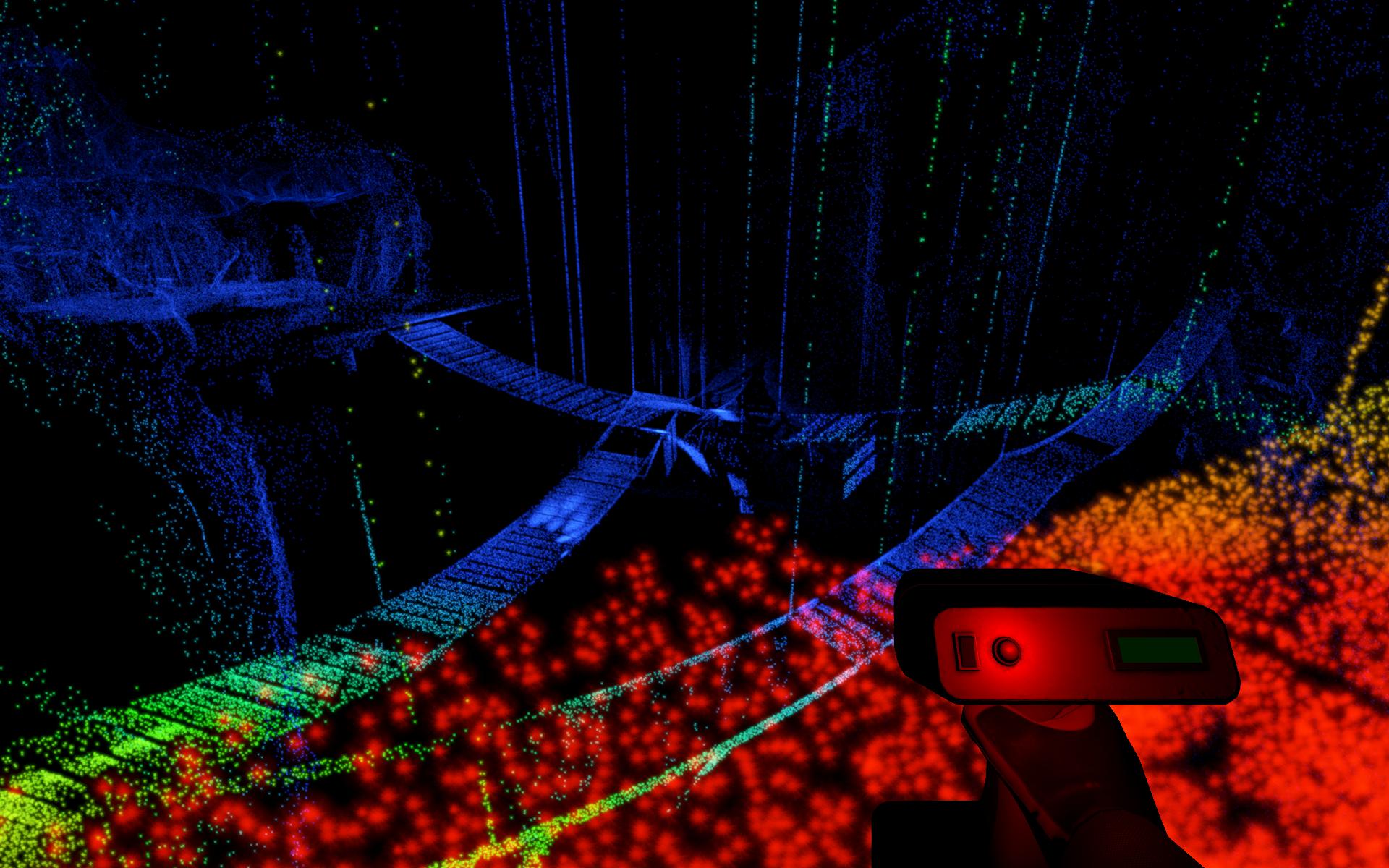

CD: It's hard to say. I mean I'm always a little bit surprised, to be honest. I can never really predict what people's responses are going to be. I think that there's something magical about it when you first see the colours and you see the depth. You scan the first room that you're in and it just looks like a load of noise, and you can't really see anything. But then as you move, and you see the points moving around you, you start to see the layout of the room and the depth of the room. There’s something kind of weirdly magical about that. And I definitely thought that at the start, and I just wasn't sure if other people were going to feel the same way.

It's completely the opposite end of the spectrum to Prison Architect, and it's a real breath of fresh air.

Chris Delay

I'm really quite glad we picked this one. I think because it's such a different game to Prison Architect as well. It's completely the opposite end of the spectrum to Prison Architect, and it's a real breath of fresh air, you know? But at the same time it's also way out of our normal comfort zone. We've never really done a first-person game before, we've never done a game where you're walking around a 3D environment, exploring it. We've never really done anything like this game internally, so it's all been quite new and I think that's been really good.

Scanner Sombre is not only a big shift from Prison Architect in terms of gameplay, but also development time. You spent six years on Prison Architect, whereas this is coming out on Wednesday.

CD: Yeah, it's fucking cool though, right? [Laughs] We're actually releasing something in a reasonable time frame for the first time ever. I think Defcon was the only other game that we ever did in a year or less. I think we really wanted it to be that; we've actually spent longer on it than we initially intended. We wanted it to be a really quick turnaround, nice breath of fresh air, nice palate cleanser as we called it internally. It would be our sixth game, but it wouldn't be like this behemoth like Prison Architect. It would just be something really strange and arty and creative, and we would just run with it and not think too much about what we were doing—just try and do something creative.

Why did you want to go that way? Why not make this LIDAR mechanic part of a larger game?

CD: It doesn't really work like that for us. It doesn't really work in the sense that we would come up with a LIDAR mechanic and then try and craft an enormous game around it. We knew that it's just one mechanic, and so I think if we tried to extend it over this enormous game, it would have probably outstayed its welcome in quite a serious way. It's kind of a visual style to some extent as well as a game mechanic, so the whole game is built around that.

The biggest gaming news, reviews and hardware deals

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

One thing that stood out to me is that you backup the visual mechanics with some really phenomenal sound design. Was that an important part of the game?

CD: Yes, it is. Sound is absolutely critical in this game. I mentioned originally that when we did the prototype I took one of our programmers, Leander, and I took Alistair, audio guy, because I knew the audio was going to be 50% of the game as far as I was concerned. Because you can't see anything, but there's no reason why you can't hear exactly what you would hear if you were there, and you can get all these hints from the size of the room that you're in and the terrain that surrounds you just from listening to the sound. And Alistair Lindsay has been an audio guy since Darwinia, so he's done the audio on every project of ours. So he did all the Darwinians by getting cats to scream and mewl and stuff, and he did all the music in Defcon, he did Multiwinia. He's just been with us for almost everything we've done.

[Audio designer Alistair Lindsay] just went absolutely mental on this game, there's no other way to describe it.

Chris Delay

MM: I'm not sure he got cats to scream, mate. He might have used samples of it, but if he was actually screaming cats, that would probably be— [Laughs]

CD: [Laughs] Oh yes, I forgot. Oh yes, yes. It wasn't a real cat, that's what you're saying. The cat was already injured. How about that? Should we go with that? [Laughs]

MM: Yeah, that's right. [Laughs] He just captured the injured cat.

CD: Yes. Maddie the cat, I believe the cat's name was. It just made these really strange sounds, it was perfectly healthy. I'm digging myself further into this hole. [Laughs] Moving on from the Darwinian cat. Yeah, Alistair just went absolutely mental on this game, there's no other way to describe it. He told me that this was basically his dream project. It's classic audio designer, he wanted a video game where there were virtually no visuals so it would just be audio selling everything. And the things that he did—I mean the footsteps allude to it, there's got to be hundreds and hundreds of different footsteps, different types of like 'walking fast', 'walking fast on gravel', 'walking fast on stone', 'stepping on wood', 'falling on wood', 'landing on wood', [laughs] 'turning on wood', it just goes on forever. He just went completely beyond the call of duty on this game and the results are just amazing.

It also gives you the emotional meaning of each level as well, and so the moments when it's quiet or the moments when it's anxious or the moments when it's scary are almost entirely coming from the audio, because nothing's really changing in the visuals. I think that Ali is basically our secret weapon. Ages and ages ago, back on Darwinia, I remember telling him that I thought that his audio made all the animations look better even though we hadn't changed the animations. They just looked visually better when they had Al's audio attached to them.

Introversion has been around for 16 years now, what's it been like to watch the indie dev revolution over the last few years?

MM: When we first started, our real crusade was the tyranny of the big publishers. We've grown up during the '90s… everything was very similar, reskins, clones, sequels. The publishing developer model I think was... 'fundamentally broken' is what I would have said at the time, you know, on stage and very vitriolic. But what it did is it only allowed a certain subset of games to be made.

I don't think [game developement is] any harder than it's ever been... this has always been a very difficult industry to thrive in.

So when the the revolution sort of started, and I'm going to quote World of Goo [as the start]. That was the first time (and we launched Multiwinia at the same time) that another small studio released something that was a hit. That was the wake up call for us. And at the start, for the first seven or eight years of our business, we traded on being like the smallest game development team in the world, and so therefore, play our stuff and help us out because we're tiny. And suddenly all of that went away. Suddenly we're just one in a sea of indies all producing great, creative output. And once I'd sort of realized that, actually, it didn't matter that we weren't the only tiny team anymore, it was just wonderful to see the creativity and the number of games that are being made nowadays.

It is interesting to me, having been in the industry for 16 years, monitoring some of the conversations and the complaints and the whining. "Oh, it's so difficult to get press to cover your game." It's always been difficult. It's always been hard. Pre-Valve, just getting the game in the hands of customers was a really tough problem, working with retail and all the rest. And Valve kind of made that problem go away, and then, you know, obviously XBLA and PSN came along and back-filled that. And the problem now is one of getting awareness out for a game, and yeah, it's very, very difficult indeed to do that. But it's better than it used to be. In the old days, if I wanted a million people to hear about me, I needed to—I don't know—have some kind of crazy relationship with the BBC or something that I didn't have. Whereas nowadays there are tons and tons of YouTubers out there, all of whom have hundreds of thousands, millions of subscribers.

Internally we had the discussions about whether we should do School Architect and whether we should do Airport Architect and all the rest of it...

Mark Morris

Now I'm not saying it's easy, I'm really not. I'm just saying I don't think it's any harder than it's ever been. And that's something that I sort of sit at the back sometimes at conferences listening to panels and things, listening to the perceived changes in the industry that suddenly made it impossible to be a success. And I look and I think it's always been like this, this has always been a very difficult industry to thrive in.

So it's just as difficult, but with different specific challenges.

MM: Yeah, exactly. So I don't need to worry about getting paid from retailers anymore. In the old days I would have to spend part of my time just chasing money from unscrupulous retailers who just wouldn't pay it. That's all gone. Your Steam back end, you get paid monthly. I mean we used to get paid a month after the end of the quarter, so you had a cashflow issue that you had to wait four months before you were going to see any money from your sales.

I think my summary is that the problems have moved, but nowadays we've got a lot more levers to pull. There are a lot more potential solutions to these problems, whereas the old days it literally was get in the elevator with the buyer from Walmart or whatever and you've got 20 seconds to get him to take your game. That's what it was like when we first started. And I'd much rather have the same problem being "there are 100 YouTubers who I need to get to cover me, I've just got get one of them or two of them."

How do you feel about so many other indie developers using Prison Architect as a model nowadays? Games like RimWorld and the more recent SimAirport are clearly heavily inspired by it.

MM: Yeah, it's interesting. I feel great about it. I certainly don't feel, and nor does Chris, like jealous or kind of embittered or, "Oh, look at that, they're ripping us off." It's very much more you do something, and obviously Prison Architect just blew away our wildest expectations and just did really well, and you realize you've tapped into something that just resonates for so many people. And then that's why you get—I mean, you could call them clones I guess, or just people that want to explore construction sims and god games in the same way. I guess part of it is that because we grew up with all those great Molyneux classics like Theme Hospital and all the rest back in the day, we don't feel like we invented this genre.

You know it would be great for me to sit here and go, "Well, we created this amazing new genre and everyone is copying us, and that's brilliant." We sort of feel like we just reminded everybody that it was there, you know? It had always just been sitting there, and then we just came along and thought "well, no one's ever done that with prisons." Did it, and it really resonated. And internally we had the discussions about whether we should do School Architect and whether we should do Airport Architect and all the rest of it, and then obviously we decided to go down a different path than that.