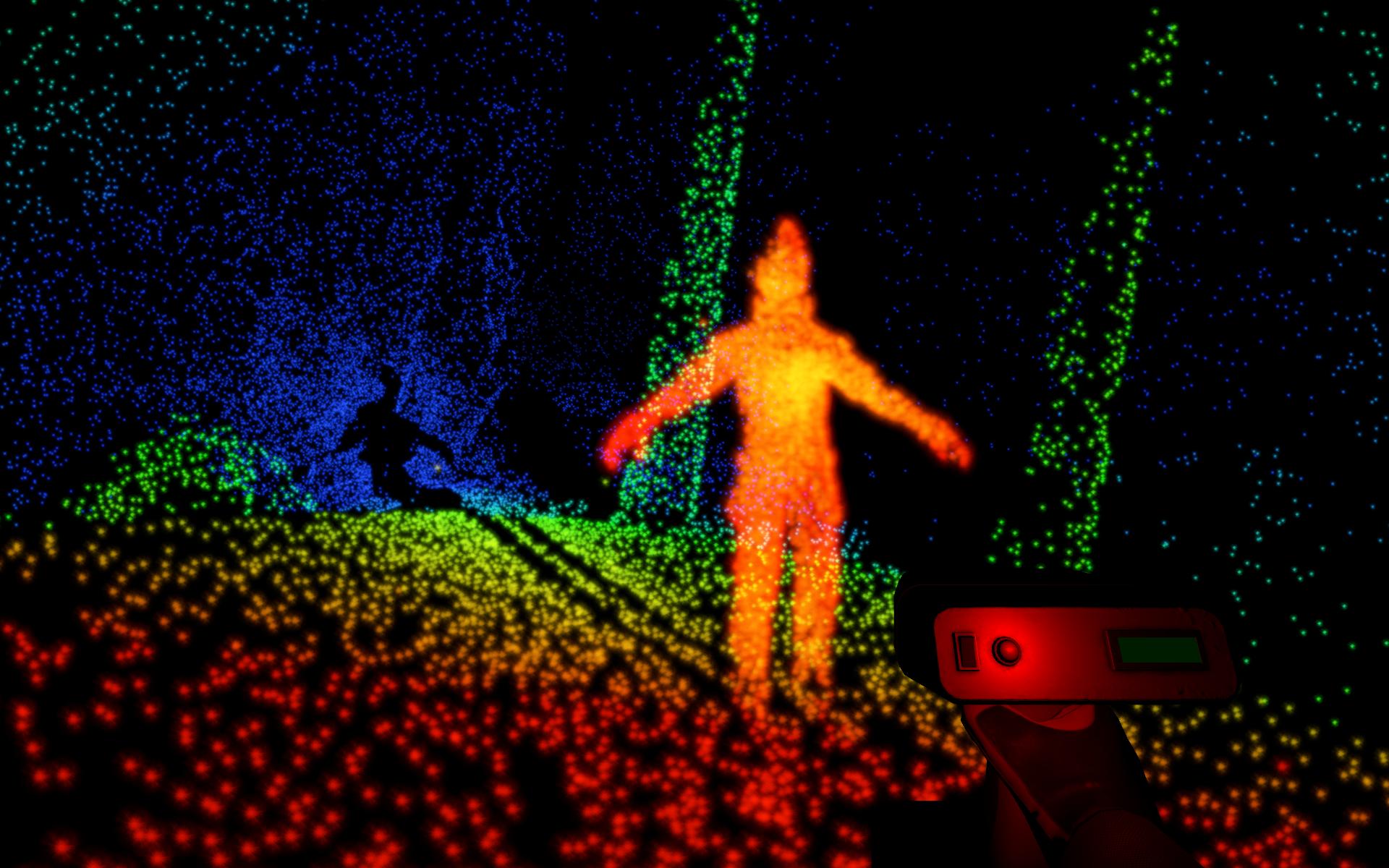

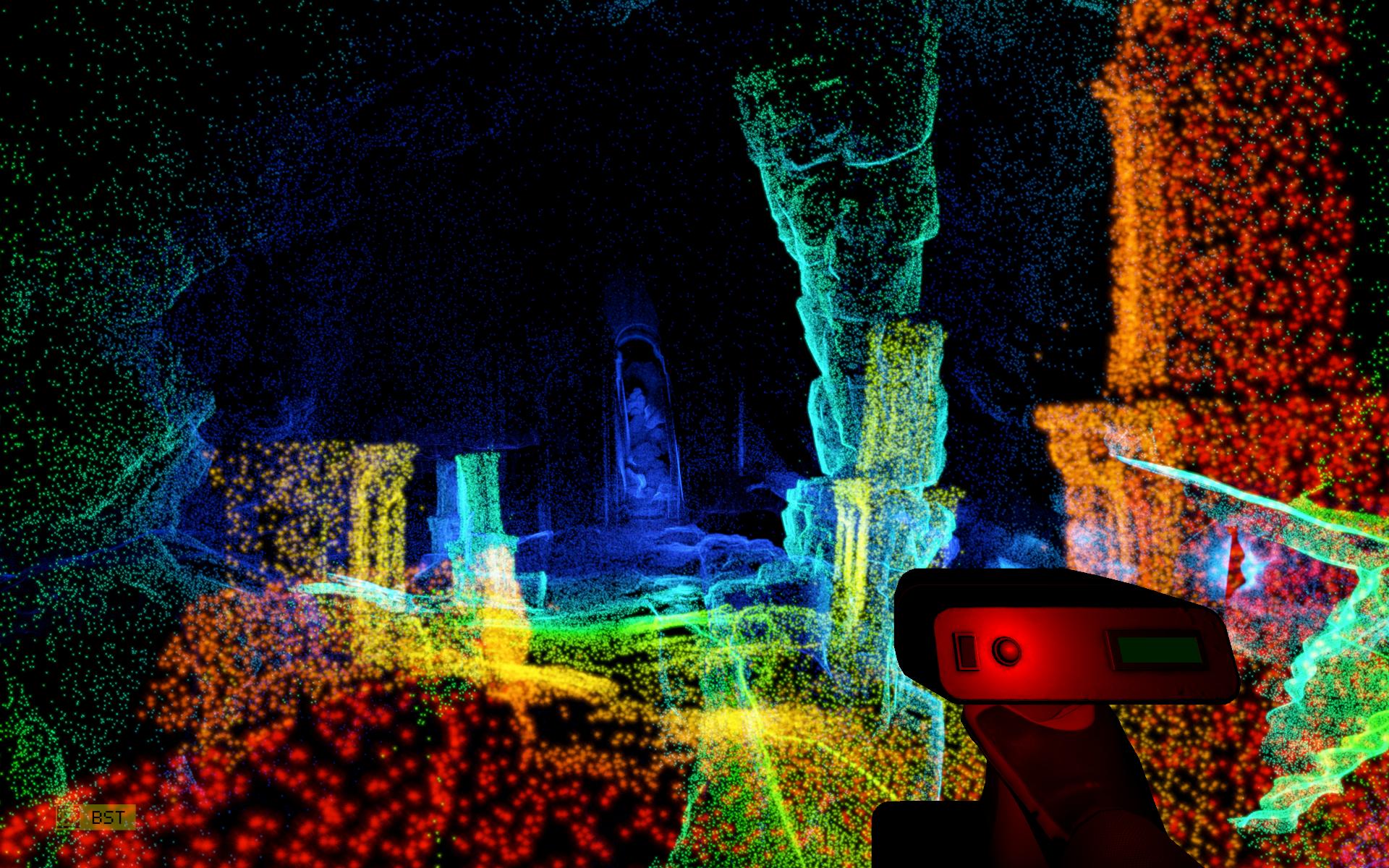

After six years of working on Prison Architect, developer Introversion Software announced today that its next game would be coming out in just a couple days on April 26. Scanner Sombre is a short first-person adventure game with one of the most unique mechanics I've ever seen: the game's world is pitch black, and you have to send out thousands of dots of light using a LIDAR scanner to reveal the terrain around you.

It's a beautiful game, and we'll have a full review when it launches this Wednesday. But before that I got a chance to speak with Introversion's lead designer Chris Delay and producer Mark Morris about the inspiration behind Scanner Sombre, its incredible audio design, how making games is (and has always been) hard, and how working on the studio's sixth game was a "palate cleanser" after Prison Architect.

PC Gamer: Where'd you get the idea to make a game with this LIDAR mechanic?

Chris Delay: It's quite an old idea, it's a pre-Prison Architect idea actually. And although it may seem like an odd source of inspiration, it's actually based on a music video that was made by Radiohead. They used this crazy LIDAR effect to kind of—they got hold of some city data or some data of buildings and trees and things, and they just kind of had it blowing around in the wind whilst this Radiohead track was playing over it making everyone really sad.

There's just something about the look of it that I really like, like all humanity has been taken out of it somehow and all you're left with is just the raw data of what's in the area. I just really wanted to use it to represent a game world, you know? Because I thought that we would be able to create a really strange atmosphere and a really strange feeling in the players when they were playing in that in that world.

How'd the structure around that mechanic come around then?

We're trying to create a certain feeling in the player, and I wouldn't quite want to say exactly what that feeling is...

Chris Delay

CD: During Prison Architect we were getting a little bit burned out, and so I took a month out from Prison Architect and I took Alistair, our audio guy, and Leander, another programmer, and we kind of just holed up in my house for like a month and made these two prototypes. And one of them was Scanner Sombre, and the other one was a bomb defusal game called Wrong Wire, and I think we prototyped Scanner Sombre in about eight days. And that was the first time we had taken the concept of a world rendered in LIDAR or a world rendered as a point cloud and actually made a game out of it. Because it seemed to me that you would naturally need to have a reason as to why there's absolutely no light. Like why can't you just see the geometry around you? Why can't you see everything? Well the answer in this particular case is that you're so deep underground that there is no light.

The biggest gaming news, reviews and hardware deals

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

Scanner Sombre has suspenseful, almost horror-like moments, but it doesn't feel like that's really the point of the game—it doesn't seem like that's its genre. What are you hoping people would get out of it?

CD: Yeah, I think you're right. We do have a little bit of horror because the mystery of it and the atmosphere of it lends itself quite well to horror. And I'm very well aware that we could have done a lot more horror if we really wanted to. But I really didn't want to. I really didn't want to do a 'jump scares in the dark' type game. There's plenty of them around. I just wanted to be a little bit more like an atmospheric kind of a mood piece, so it would be uncomfortable and it would be unnerving but it wouldn't be full on horror.

We're trying to create a certain feeling in the player. And I wouldn't quite want to say exactly what that feeling is, but it's certainly very different from the feeling of playing Prison Architect. I guess it's like exploring a strange place, you know? Exploring somewhere that not only you've never been to but also looks completely different, like the effect of just seeing it as a rainbow point cloud creates a feeling in you that is very different from just having like a small flashlight that has a really limited range. It creates a very different feel, because you can't see anything but at the same time you can kind of see everything all around you, like everywhere you've been.

From a technical standpoint, how'd you go about implementing the LIDAR effect? I imagine saving the position of all those teeny tiny dots and having what seems to be an infinite number of dots possible on the screen would be demanding.

CD: Yeah, it is. It is. I don't know how to describe it, it is just a giant particle system. And people have been saying, "Why on Earth do we have to have unlimited particles? Why can't we just cap it or something?" But a lot of effort behind-the-scenes has gone into making it possible to have this enormous particle cloud. And if you look behind you [in the game], everything you see is all the particles that you've created and scanned. It's almost like you've painted the whole map yourself.

Mark described it as programmer art because you don't see any of the visuals that we've created. All you can see is the cloud of points that you've created by walking around with this gadget. And yeah, that's the short answer. Yes, it was really hard. [Laughs] It took us ages. We started out using a particle system that stopped working after about 10,000 particles, and then ended up [restarting] basically entirely from scratch just so that we could have enough particles on screen to make it look as dense as it does.

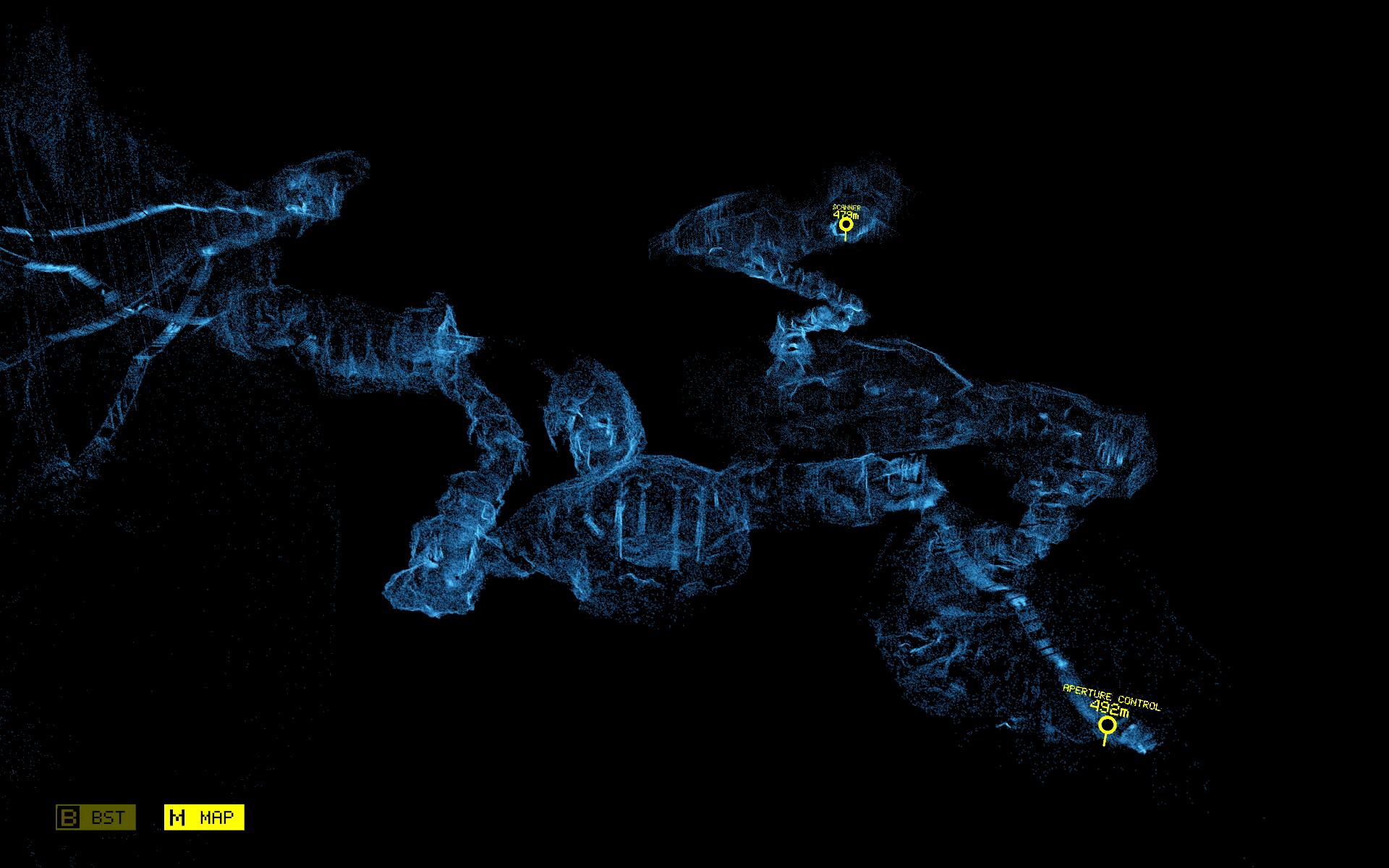

It was stunning to look back at the in-game map and think, "Those can't possibly be all the exact dots I placed, right?" But they are, and it makes the levels feel very personal.

[The map] really is all the points that you've created, it's definitely not faked.

Chris Delay

CD: The map is definitely there to help for a lot of different reasons, but part of it is just that it's such a nice way to visualize the location as well. And it really is all the points that you've created, it's definitely not faked. I've never really seen a video game map like that, you know? When you go at the video game map, it's normally a much simpler polygonal-type flat surface with some ramps and things, and you can tell it's been modeled separately. I really didn't want it to be like that, I wanted it to look like a real LIDAR scan that you were looking at, that you could spin around and move the camera around and view it from different angles.

You mentioned the Wrong Wire prototype, which is actually available to play within the game, but what made you choose to do Scanner Sombre over it?

Mark Morris: Chris very much likes to go and sort of do his own thing and rebel a bit. And often he'll do that whilst in the middle of critical phases on other projects. I think it's kind of part of his sanity is to take that time away and flex his creative muscles. And this time, for the first time actually—

CD: [Laughs] It's like you're speaking about your own child when you're discussing this. “He occasionally likes to act out.”

MM: Yeah, that's how you behave. [laughs]

CD: "It's all part of his charm, really. We like him, really."

MM: So Chris does that and this time, at the end, he sat me down with Scanner and Wrong Wire and said "you know, Mark what do you think we should take forward?" And my view is more a sort of commercial point of view, Chris is all about creativity, and both of us felt that Wrong Wire was probably the most commercial of the two—the safer bet if you like. But even the very first prototype of Scanner, I found it to be really emotionally engaging. We were just in a coffee shop in London, and I finished my 20-minute play through with loads of people around and I was sweating all over. It just really got under my skin. And even though we sort of put it on the backburner a bit and thought, "Well, that's alright, but Wrong Wire is better," we showed it to the team and the team kind of had exactly the same reaction. They said, "Well, I think that Wrong Wire is going to be a bigger game, it's going to find a market easier. But there's something quite unique and special about Scanner."

I think it's probably been the most rigorous process we've ever applied to deciding on an Introversion game.

Mark Morris

And that's when Chris and I started thinking, "Well, hang on a second; actually making a game that touches you in that way is very, very difficult, and it's very, very difficult to design for that." You can't really put down in your design brief, "It's going to be emotionally stimulating" or whatever, that just kind of happens I think. Which is why we thought, "Well, we've got [EGX] Rezzed, we've got this consumer show, we're going to have a thousand people or something coming through the doors over the three days. Why don't we test out what we think about the game with them?" Rather than saying, "What do you think the next game should be?" Because that sort of suggests that the other one will never be made, we just asked them, "What game do you think we should work on next?" And about three quarters of them said, "We think you should work on Scanner Sombre next." So we took that as good confirmation of the way we were leaning.

And then finally, we did do a kind of online vote with a couple of videos just to rule out that we were telegraphing to people that we really wanted to do Scanner at the show. Just off the back of a couple of videos, what do the interwebs think? And the results of that were about 50/50, and we kind of felt that that was a very positive indication that there were a lot of people out there who were interested to play Scanner. So that was the process that we went through this time to down-select, if you like. I think it's probably been the most rigorous process we've ever applied to deciding on an Introversion game.

On the next page: Why Scanner Sombre is a "breath of fresh air" after Prison Architect, how their audio guy went "absolutely mental", and what they think of games like RimWorld.