Intel could be heading towards an AI-powered frame generation future, thanks to a research group's work, dubbed ExtraSS

Wonder what it would be called, though: XeExSS? Umm, maybe not.

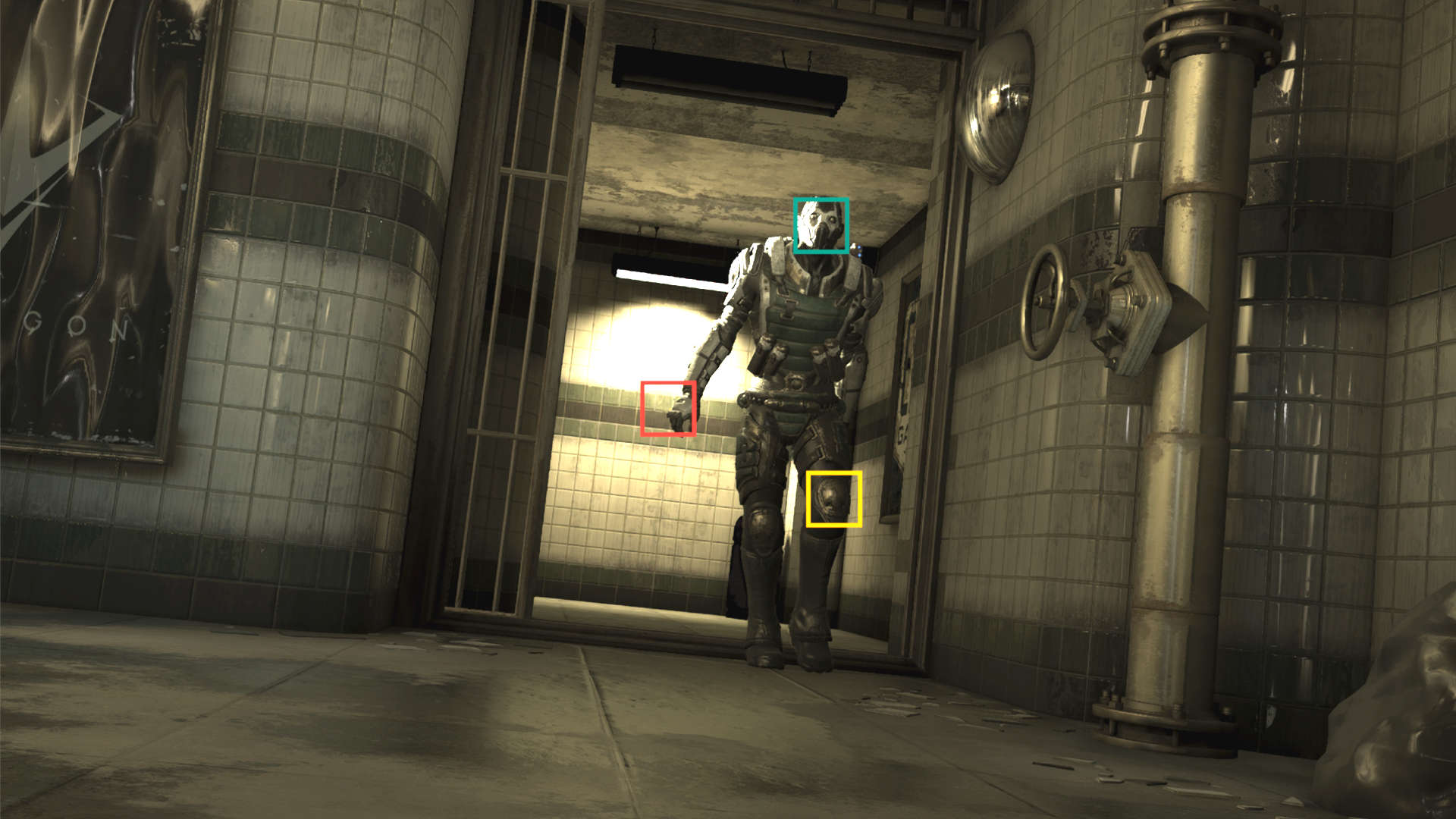

Researchers at the University of California and Intel have developed a complex algorithm that leverages AI and some clever routines to extrapolate new frames, with claims of lower input latency than current frame generation methods, all while retaining good image quality. There's no indication that Intel is planning to implement the system for its Arc GPUs just yet but if the work is continued, we'll probably have some Intel-powered frame generation in the near future.

Announced at this year's Siggraph Asia event in Australia (via Wccftech), a group of researchers from the University of California was sponsored and supported by Intel to develop a system that artificially creates frames to boost the performance of games and other applications that do rendering.

More commonly known as frame generation, we've all been familiar with this since Nvidia included it with its DLSS 3 package in 2022. That system uses a deep learning neural network, along with some fancy optical flow analysis, to examine two rendered frames and produce an entirely new one, which is inserted in between them. Technically, this is frame interpolation and it's been used in the world of TVs for years.

Earlier this year, AMD offered us its version of frame generation in FSR 3 but rather than relying on AI to do all the heavy lifting, the engineers developed the mechanism to work entirely through shaders.

However, both AMD and Nvidia have a bit of a problem with their frame generation technologies, and it's an increase in latency between a player's inputs and then seeing them in action on screen. This happens because two full frames have to be rendered first before the interpolated one can be generated and then shoehorned into the chain of frames.

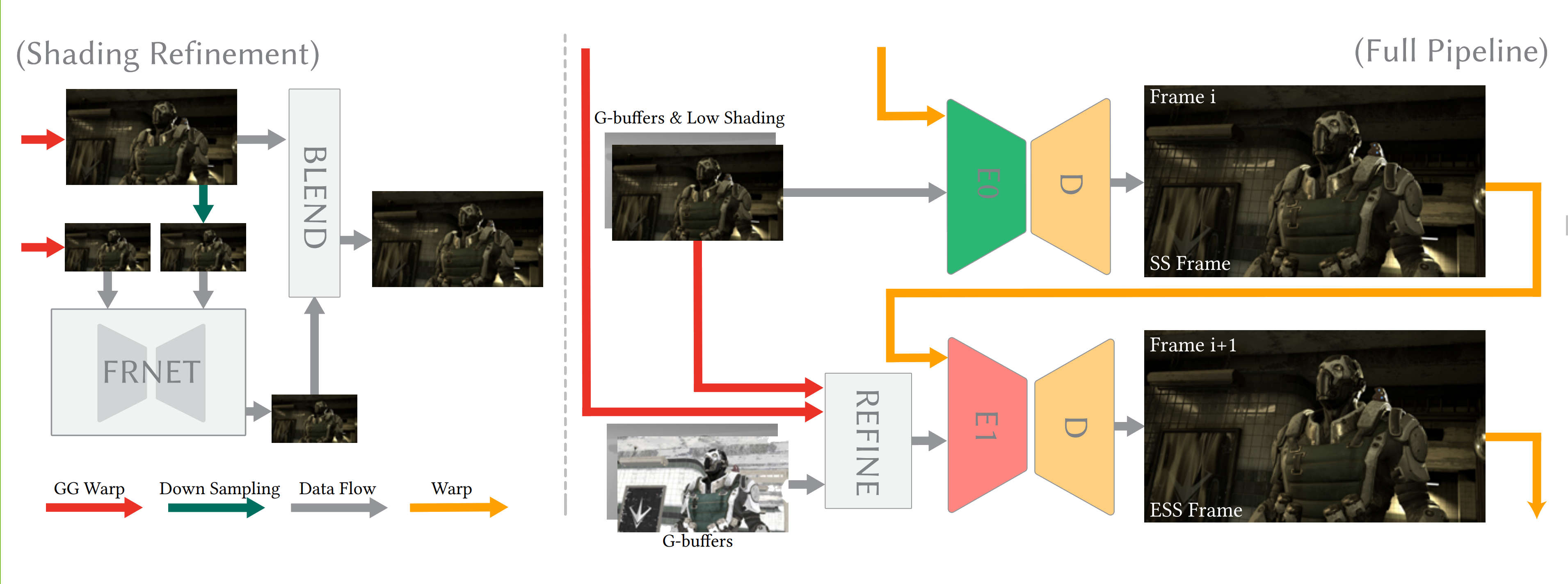

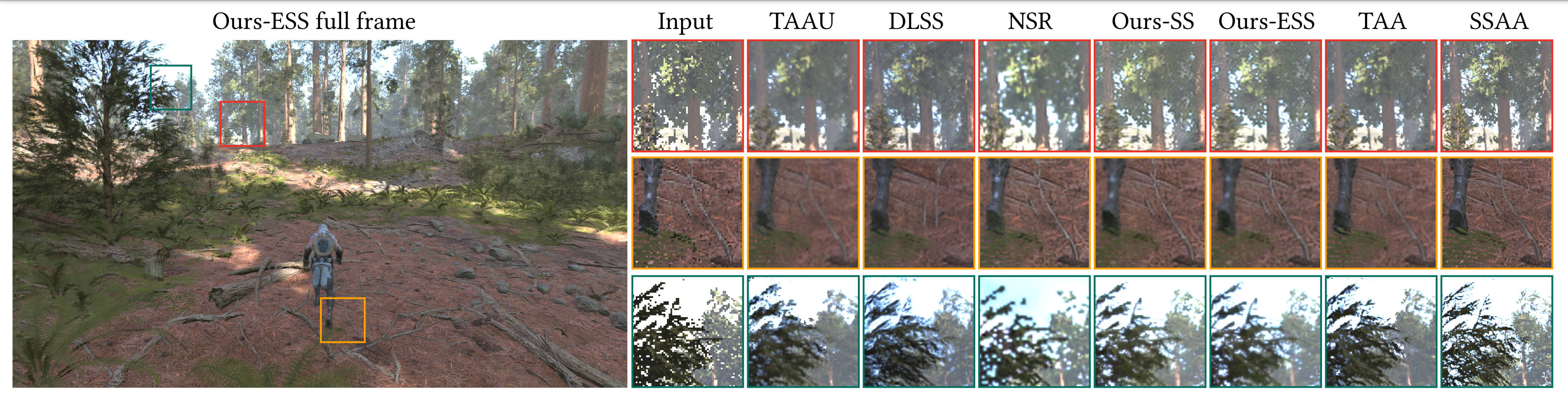

The new method proposed by Intel and UoC is rather different. First of all, it's three methods, all rolled into one long algorithm. The initial stage eschews the use of motion vectors or optical flow analysis and instead relies on some clever mathematics to examine geometry buffers created during the rendering of previous frames.

That stage makes a partially complete new frame which is then fed into the next stage in the whole process, along with other data. Here, a small neural network is used to finish off the missing parts. The outputs from stages one and two are then run through the final step, involving another neural network.

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

It's all far too complex to go into detail here but the result is all that matters: A generated frame that's extrapolated from previous frames and inserted after them. You're still going to get a bit of input latency but, in theory, it should be less than what you get with AMD and Nvidia's methods but real frames are presented immediately after rendering.

If this sounds all a little too good to be true, well there is one notable caveat to all of this and its performance. The researchers tested how long the algorithm would take to run, using a GeForce RTX 3090 and TensorRT to handle the neural networks.

Starting at 540p, with the final generated frame coming out at 1080p, the process took 4.1 milliseconds to complete. That's very quick, though the research paper also notes that starting at 1080p, the algorithm took 13.7 ms and that's equivalent to a performance of 72 fps.

Best CPU for gaming: The top chips from Intel and AMD.

Best gaming motherboard: The right boards.

Best graphics card: Your perfect pixel-pusher awaits.

Best SSD for gaming: Get into the game ahead of the rest.

More work will clearly be done on the whole thing and any implementation of it would need an additional system to manage the pacing of the real and fake frames, otherwise the fps would be spiking all over the place.

And if Intel does bring it to market, the fact that it runs two neural networks means that any GPU with dedicated matrix hardware would be a clear advantage (i.e. Intel and Nvidia).

One thing is certain, though: Upscaling and frame generation are here to stay and will only become increasingly more important in how graphics cards and games work together in the future.

You might not be a fan of them at the moment but eventually, there will come a point in time when you won't be able to notice them in action. You'll just be enjoying the game, either with mega levels of graphics or super high frame rates.

Nick, gaming, and computers all first met in the early 1980s. After leaving university, he became a physics and IT teacher and started writing about tech in the late 1990s. That resulted in him working with MadOnion to write the help files for 3DMark and PCMark. After a short stint working at Beyond3D.com, Nick joined Futuremark (MadOnion rebranded) full-time, as editor-in-chief for its PC gaming section, YouGamers. After the site shutdown, he became an engineering and computing lecturer for many years, but missed the writing bug. Cue four years at TechSpot.com covering everything and anything to do with tech and PCs. He freely admits to being far too obsessed with GPUs and open-world grindy RPGs, but who isn't these days?