Illegal and important: the catch-22 of PC fan games

The legal issues with fan games, and why they're an important part of the PC ecosystem, anyway.

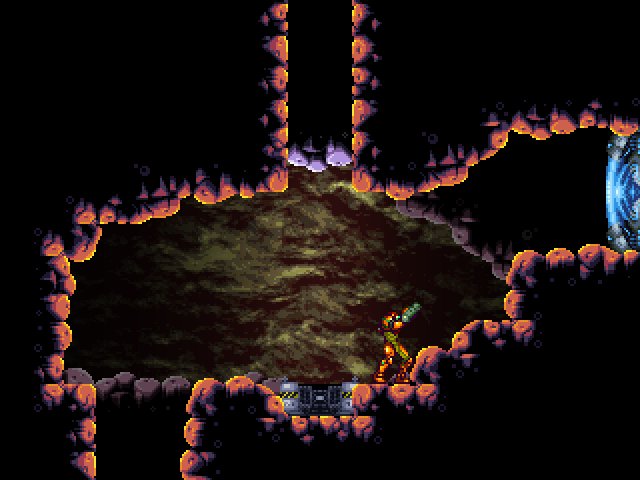

Here’s a sentence you may have read on PC Gamer a week ago: “The impressive fan remake of Metroid II is out now after over eight years of development.” Here’s another one: “After 15 years, a cancelled Game Boy RPG finds life on PC.” We see permutations of this headline year after year, and each one reminds me of my absolute favorite thing about PC gaming: the passion to create and preserve. That the PC is where the most elite, driven, and talented game fans focus their efforts to expand, improve, and save the games they care about most deeply. And that they’re doing it for free, on nights and weekends, in the time many of us spend playing games.

The developer of AM2R (that impressive Metroid II remake), Milton “DoctorM64” Guasti, didn’t even know how to program when he started. “There weren't that many game engines back [in 2006], and I didn't have the knowledge to make my own,” he wrote to me last week over email. “Game Maker turned out to be simple to learn. I ended up learning programming while I added Metroid specific features to a platform game engine.” Despite its GameMaker roots, AM2R feels like a bona fide 2D Metroid game, the kind Nintendo hasn’t made since 2004’s Zero Mission, itself a remake of Metroid for the NES.

Great fan games exemplify the core spirit of PC gaming. Unfortunately, they’re also illegal.

Showdown at the copyright corral

Hours after AM2R was released to the public—10 years after DoctorM64 first started privately building it in GameMaker—one host, Metroid Database, was hit with a DMCA takedown notice from Nintendo. Other hosts followed. Download links began to disappear.

Days later, another group of fans released Pokemon Uranium for PC, a project nine years in the making. It, too, had download links on multiple sites taken offline by DMCA notices, and the developers chose to stop hosting the game themselves, writing “it’s clear what [Nintendo’s] wishes are, and we respect those wishes deeply.” At that point, Pokemon Uranium had already racked up 1.5 million downloads, so removing the link means little. The code is out of the bottle. It’ll live on the internet forever.

“I knew something like this could happen, but what caught me off guard was how quick things developed,” Guasti said. “I haven't had any trouble during development, even after releasing several successful demos. Part of me wished for official recognition, or at least to continue developing the game as always.”

This is a common story. The more ambitious the fan creation, the more publicity it gets, the more likely it is to die by the stroke of a corporate letterhead. Is that inevitable? Gamers who defend these publishers often argue that companies need to “protect their IP,” as if copyright is a use-it-or-lose-it defense. Is that really how it works, legally?

The biggest gaming news, reviews and hardware deals

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

According to lawyer Ryan Morrison, the answer is yes. But Morrison also says that’s not the driving force behind DMCA takedowns. “Is it possible to lose your trademark or copyright due to non-enforcement? Yes, but it's very difficult to actually let that happen,” he wrote over email. “Instead, most companies just don't want thousands of people stealing their ideas and assets to try and profit off of [them]. If you hit their radar, they are going to smack you down.”

The communities around fan games would argue there’s no profit happening here—these games are distributed for free and never promoted as “official,” though they do of course borrow the intellectual property (and sometimes ripped assets) of the series they’re based on. But Morrison says Fair Use, which is sometimes thrown around online as a defense, doesn’t apply.

Free is a factor in favor of fair use, but you can still be causing harm in the marketplace by just existing. — attorney Ryan Morrison

“Free does not mean fair use, and that's the most common misconception I see on the internet,” he wrote. “Free is a factor in favor of fair use, but you can still be causing harm in the marketplace by just existing. Why would I buy someone's product when I can get a free version instead? Then it causes actual harm to that product line if the free product is substantially inferior. People own their intellectual property, and you are not allowed to do whatever you want with it under the guise of ‘we aren't charging.’ … Is your fan game hurting a product that exists or may potentially exist for the original IP holder? Then it's not OK,” he wrote. “I'm a huge advocate for standing up for the little guy and the indie dev, but there is no place to argue that fan games like these are [legally] OK.”

As disappointing as it is for fans to see projects like AM2R and Pokemon Uranium hit with DMCA notices, let’s put things in perspective: Nintendo’s hardly gone for the jugular to defend its IP. It hasn’t sued the creators, or even sent them threatening cease and desist letters the way Square Enix has with past projects like Chrono Resurrection.

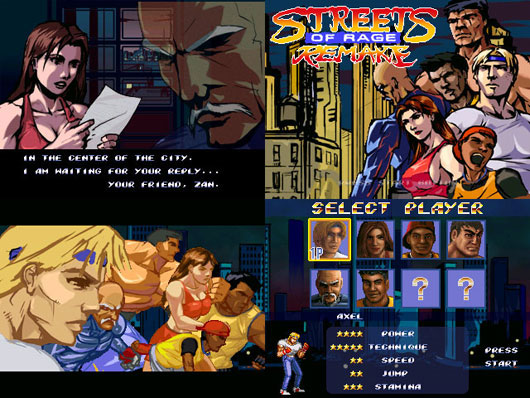

According to Guasti, he was never contacted about taking down AM2R. The statement from the Pokemon Uranium developers said the same. Nintendo also had ample time before either was released to take them down. If Nintendo really didn’t want these projects to exist, it could have been much more aggressive. Instead, the DMCA notices only targeted specific download links. The same thing has happened in the past, like with the Streets of Rage Remake. That project got so much attention, Sega hit some download links with DMCA notices—but only after it was released. SORR is still easy to find online.

As of now, AM2R and Pokemon Uranium may have had some official links removed, but they are still widely available. Why? And why did Nintendo wait for years, until they were released, to even do that much?

The goodwill equation

Fan games, like other uniquely PC fan creations—mods and emulators—arguably cost developers money. Nintendo wants you to buy Pokemon and Metroid on its consoles, and a satisfying PC fan game, even a free one, could mean lost sales of hardware or software. But fan games and mods do generate awareness and goodwill, two things that I think are ultimately almost as important as sales, even if they’re much harder to measure. Perhaps Nintendo realizes that, and understands harsher legal action would do more harm than good. But there are even better alternatives to DMCA notices.

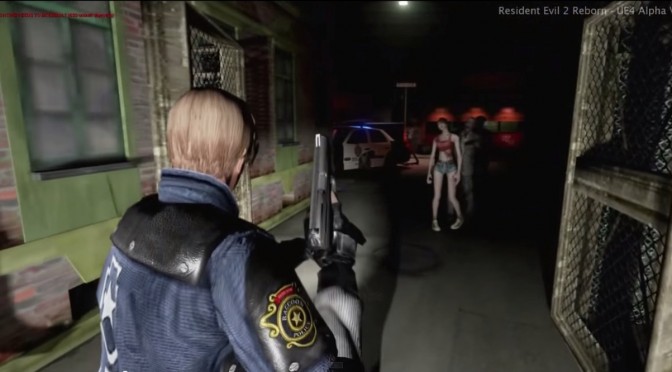

In 2012, Capcom decided to officially support and release fan game Street Fighter X Mega Man instead of shutting down the project. It pulled in more than a million downloads. And when a Resident Evil 2 fan remake in progress went viral, Capcom reacted, directly asking fans if they were interested in a Resident Evil 2 remake. Within weeks an official remake was greenlit, and Capcom got in touch with the creators to tell them an official project was also in the pipe and asked them to discontinue their own.

Instead of disappointing fans by shutting down what looked like a promising project, Capcom showed that they were listening and earned goodwill instead of burning it. In cases like Resident Evil 2, fans get it—game developers have to make money, and a fan remake of a game that could be officially remade sometimes crosses a line into damaging territory.

Valve is unusually supportive of fan games, which is just one of the reasons the company is generally so revered. Valve once said of Black Mesa, the fan remake of Half-Life 1, “we’re as eager to play it here as everyone else.” Years later, Valve approved Black Mesa on Steam Greenlight, which I’d call an official thumbs up. And unlike most fan games, Black Mesa is actually being sold. It’s $20, and might have about 300,000 owners, according to SteamSpy. Valve approved Half-Life 2 fan game Prospekt for Steam, too.

Of course, Valve is in the unique position to profit from fan games being sold on Steam; it earns 30% of every sale, and likely wouldn’t be so generous with fan games if that weren’t the case. But companies like Nintendo could follow Capcom’s lead—instead of shutting down the most ambitious fan games, they could earn goodwill by supporting them.

Fan games do violate copyright law, and inevitably companies like Nintendo need to either shut down the most high profile cases or find a way to work with them. But setting aside the legal issue, fan games are a natural result of the spirit of PC gaming—that drive to create and tinker and build on something you already love—and a great thing for fans who supported the growth of these series in the first place.

The gamers who play these games aren’t the shoppers who buy off the shelf on a whim at Walmart; they’re the ones who still post on Metroid message boards even though the last good Metroid game was released in 2007. And the fans who create them sometimes have a better feel for what fans want from a series than the developers themselves. The recently announced Sonic Mania is a collaboration between Sega, indie developers, and fan developer Christian Whitehead, whose work on Retro Sonic landed him a gig with Sega porting old Sonic games to modern platforms.

There’s no better outcome for a fan game than that legitimacy, and Sonic Mania is a perfect rebuttal for an argument I often see: that talented fans should create their own properties, not build on someone else’s. I asked Guasti what he thought of that claim.

“Once AM2R became public, I suddenly realized I wasn't the only one that wanted to play Metroid 2 with improved controls and graphics,” he wrote. “If I were to abandon the game to make something original, it'd be just another cancelled fangame. But most importantly, I'd be disappointing a lot of fans, including the talented people who helped using their valuable free time.”

Outside of fan remakes, the PC has a long, rich history of young modders graduating to successful developers by building on the backs of existing engines or games. Tim Willits got his job at id after creating impressive Doom maps. The young modder who created Skyrim mod Falskaar as an application to Bethesda ended up landing a job at Bungie. Valve hired Counter-Strike’s creators and Dota designer IceFrog to develop those mods as standalone games.

Making fan games is just another way of putting that passion to work. Perhaps Nintendo is tacitly letting fan games exist by sending DMCA takedowns instead of more aggressive cease & desists. Perhaps not. But the sooner more developers recognize fan games are too ingrained in the spirit of PC gaming to completely stamp out, the sooner they can make the best of them—by recognizing their creators and players as their most passionate fans, and either supporting them or treating them with a light legal touch. All that goodwill is there for the taking.

Wes has been covering games and hardware for more than 10 years, first at tech sites like The Wirecutter and Tested before joining the PC Gamer team in 2014. Wes plays a little bit of everything, but he'll always jump at the chance to cover emulation and Japanese games.

When he's not obsessively optimizing and re-optimizing a tangle of conveyor belts in Satisfactory (it's really becoming a problem), he's probably playing a 20-year-old Final Fantasy or some opaque ASCII roguelike. With a focus on writing and editing features, he seeks out personal stories and in-depth histories from the corners of PC gaming and its niche communities. 50% pizza by volume (deep dish, to be specific).