How Turtle Rock Studios righted itself after rolling on its back

From zombies to zombies, by way of some misplaced Kaiju.

This article first appeared in PC Gamer magazine issue 365 in January 2022, as part of our 'DNA Tracing' series, where every month we delve into the lineages behind iconic games and studios.

One commonly accepted piece of games industry wisdom is that ideas are cheap; everybody has them. It's the execution that's difficult and expensive. But it's evidently not a philosophy shared by Valve, which has long bought its best ideas.

Counter-Strike, Portal, Team Fortress, Dota – all were first dreamed up outside Valve by modders or students. Again and again, the studio has acted as a kind of incubator – hiring on creators and giving them resources and expertise, so that they can take those magic ideas to their big-budget conclusion.

Often, in time, those creators fade into the grey anonymity of Valve – contributing to the studio's brain trust in ways both crucial and imperceptible to the general public. But one team has retained not only its distinct identity but a degree of wider recognition: Turtle Rock, the outfit behind Left 4 Dead.

Perhaps that's because Turtle Rock built the vast majority of its most famous game as an independent. Valve had reason to trust the studio – as a contractor, Turtle Rock had effectively become the custodian of Counter-Strike – and so largely left its team alone during Left 4 Dead's development, providing funding and the services of acclaimed Portal writer Chet Faliszek.

Valve's greatest contribution to Left 4 Dead was actually the organic and full-throated enthusiasm of its staff, who quickly adopted the game for their play sessions outside work. They demonstrated the argument – so obvious to us now – that the FPS genre was missing a trick with casual co-op. Turtle Rock was reacting against Counter-Strike's baked-in competition; put simply, the team was sick of fighting each other.

Counter, Terror

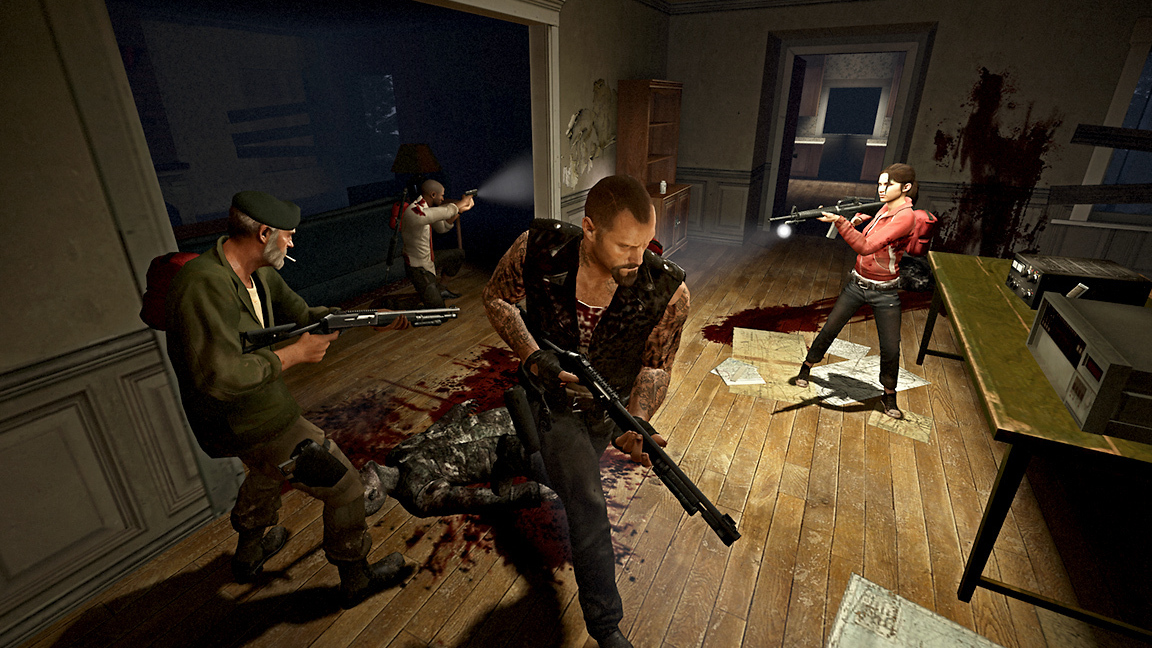

What began as a goofy CS mod named Terror – in which bloodily-textured bots armed with knives ran eerily at a squad of four friends – became the follow-up to Half-Life 2. Valve acquired its developer briefly before launch, which meant Turtle Rock's name wasn't on the box. But not long afterwards, the studio spun out on its own again.

As Valve South, the team had missed its independence, and struggled to communicate with its colleagues 800 miles away in Seattle. In the end, it was Gabe Newell who suggested a return to the way things had been – signing back Turtle Rock's name and logo. Valve would handle Left 4 Dead 2 internally, while Turtle Rock worked on its DLC (as well as more Counter-Strike, the studio's spiritual default).

The biggest gaming news, reviews and hardware deals

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

As you know, Left 4 Dead changed the industry. Alongside 28 Days Later, it rehabilitated cheesy old zombies in pop culture, rendering them terrifying once again with a simple speed buff. What's more, Turtle Rock's easygoing, chat-friendly approach to PvE – in which it paid to put the team before yourself – paved the way for COD: Zombies, Payday, and Vermintide.

Yet it was the game's lesser-played Versus mode that mapped a path to the studio's future. There, four players took on the roles of the Special Infected, mastering bizarre abilities with the goal of halting and separating a team of survivors as they pushed through a campaign map. Where competitive shooters had traditionally balanced two teams with identical toolsets, Left 4 Dead embraced asymmetry, asking zombie players to become walking bombs and sentient lassos.

Stage Two

Evolve took that imbalance to its logical endpoint, tipping the seesaw as far as it would go. Turtle Rock's sophomore effort cast a single player as a monster, and four others as the hunters tasked with trapping and killing the beast. One side was playing a co-op shooter in the mould of Predator; the other a strange stealth game about troughing on an alien ecosystem until you were so engorged as to be unstoppable.

"This ain't about just running around and shooting bad guys like you're some kind of goddamned Navy Seal or whatever," drawled your guide in Evolve's tutorial. "You are hunting a monster on an alien planet, and that ain't like anything else. You already know how to use a gun and run around and how to face which direction and all that bullshit – you're not an idiot. We're gonna teach you monster hunting. It may seem… it's a lot to deal with, but after only like three or five matches, you'll get it."

It's hard to know whether Turtle Rock's high opinion of players – both their intelligence, and their appetite for novelty – would have been rewarded in the long-term. Evolve was already hamstrung at release by a punitive pricing policy, introduced by 2K, who had picked up the game after original publisher THQ went bankrupt.

"If your customer needs to find four friends to enjoy your game, maybe don't charge $60 for it," says Turtle Rock lead writer Matt Colville in a Reddit postmortem three years ago. "Because getting your friends to spend a total of $240 on a game is a hard fucking sell. We were already thinking about this. We knew this, and THQ knew it. Alas, THQ went tits up."

Turn left

Evolve ultimately went tits up too, shutting down after a brief free-to-play redesign. Besides the price, Colville partly attributes that outcome to sheer design challenge. "It wasn't just asymmetrical," he says. "The two sides were playing fundamentally different games. That was a problem we never solved. It meant all new content was a colossal pain to implement, forget balance."

Given the cost of all that ambition, it should be no surprise that Turtle Rock has since retreated to more familiar ground. This year it put out Back 4 Blood – the Left 4 Dead 3 that Valve, with its democratised development process, seems unable to rally its workforce around. Back 4 Blood's genius is that it preserves Left 4 Dead's core in amber – or, if you prefer, secures it in a safe room.

The modern touches intended to give the game longevity, like the deck of unlockable cards that offer percentage tweaks to health or reload time, are merely layered on top – there to be engaged with if you want to, or not. Turtle Rock knows better than to mess with the rock, paper, scissors simplicity of its premise. A hulking boss is still best dealt with using napalm; a horde lured away with a pipe bomb.

It's not exactly evolution. In fact, if Turtle Rock were a monster from its most famous failure, you could say it had reverted to Stage 1, rather than grown into its most powerful, final form. But let's allow the studio this one, fond throwback. Doesn't Turtle Rock deserve to rest on its laurels when, for so many years, those laurels were mistakenly handed to Valve instead?

Jeremy Peel is an award-nominated freelance journalist who has been writing and editing for PC Gamer over the past several years. His greatest success during that period was a pandemic article called "Every type of Fall Guy, classified", which kept the lights on at PCG for at least a week. He’s rested on his laurels ever since, indulging his love for ultra-deep, story-driven simulations by submitting monthly interviews with the designers behind Fallout, Dishonored and Deus Ex. He's also written columns on the likes of Jalopy, the ramshackle car game. You can find him on Patreon as The Peel Perspective.