How the creators of Hitman use social science to design perfect murder playgrounds

The real world shapes the flow of Hitman's sprawling sandboxes, says its level designer.

In some ways, the Hitman games are more like Rube Goldberg machines than pure science. Taking out targets becomes an experiment in making a target move to the right point, and then manipulating an object to crush, electrocute, or blow them away. But that doesn’t mean there isn’t a bit of humanities studies going on too. IO Interactive level designer Mette Podenphant Andersen explained how the studio used some sneaky social science to make some of the series’ most standout levels feel like the perfect murder playgrounds.

“When we looked at reviews for Sapienza, few of them had anything to do with the mission,” Andersen said. “It was all about walking around this beautiful village full of characters and places to visit. Instead of how do you make an awesome level, I wanted to find how do you design everyday life?”

Like most artists, Andersen admits she’s only taken about one semester of social anthropology, but the class gave her the chance to think more critically about how Hitman levels flow, how they affect players’ mental states, and how believable it is that people would live in a place soon to be filled with corpses and piles of clothing.

Interestingly enough, Andersen cited two noted sociologists of the mid 20th century: Pierre Bourdieu and Erving Goffman. Among other important things, Bourdieu popularized the theory of social spaces, and how different social spaces carry different sets of rules, like “please don’t electrify this puddle of water”. Similarly, Goffman popularized the theory of “front stage vs. back stage,” which Hitman fans should definitely be familiar with. The general idea is that humans have a forward-facing personality in public, and a backstage personality we bring out in more private circumstances, such as when we’re with loved ones alone in our bedroom. Similarly, it can be applied to social groups we inhabit, like sitting in stands belonging to a sports team, or going to church.

Those principles help fuel much of Hitman’s level design, working to instruct players how to successfully navigate a Miami race track, or even a gothic castle filled with Eyes Wide Shut extras, without sacrificing a level of believability.

“We're designing rules of behavior,” Andersen said. “We're designing something that's going to tap into your knowledge of ‘how should I be in this place?’"

“[Bourdieu’s] idea is basically that we are all in the social marketplace exchanging capital,” Andersen said, connecting the concept to Agent 47’s disguises. “If you do one thing in one social group that's going to get you in, in a way. For instance, if I buy a fur coat. In one social group, that's going to make me look so cool. In another one, they're going to hate me for it.”

The job of level designer for Hitman very much blends artistic design and overall game design, according to Andersen.

The biggest gaming news, reviews and hardware deals

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

“We're designing rules of behavior,” Andersen said. “We're designing something that's going to tap into your knowledge of ‘how should I be in this place?’ It's very subtle. People walk into these spaces and they don't go 'oh, I'm in a church and now I must act like this.' They just do it without thinking. That's a very powerful thing."

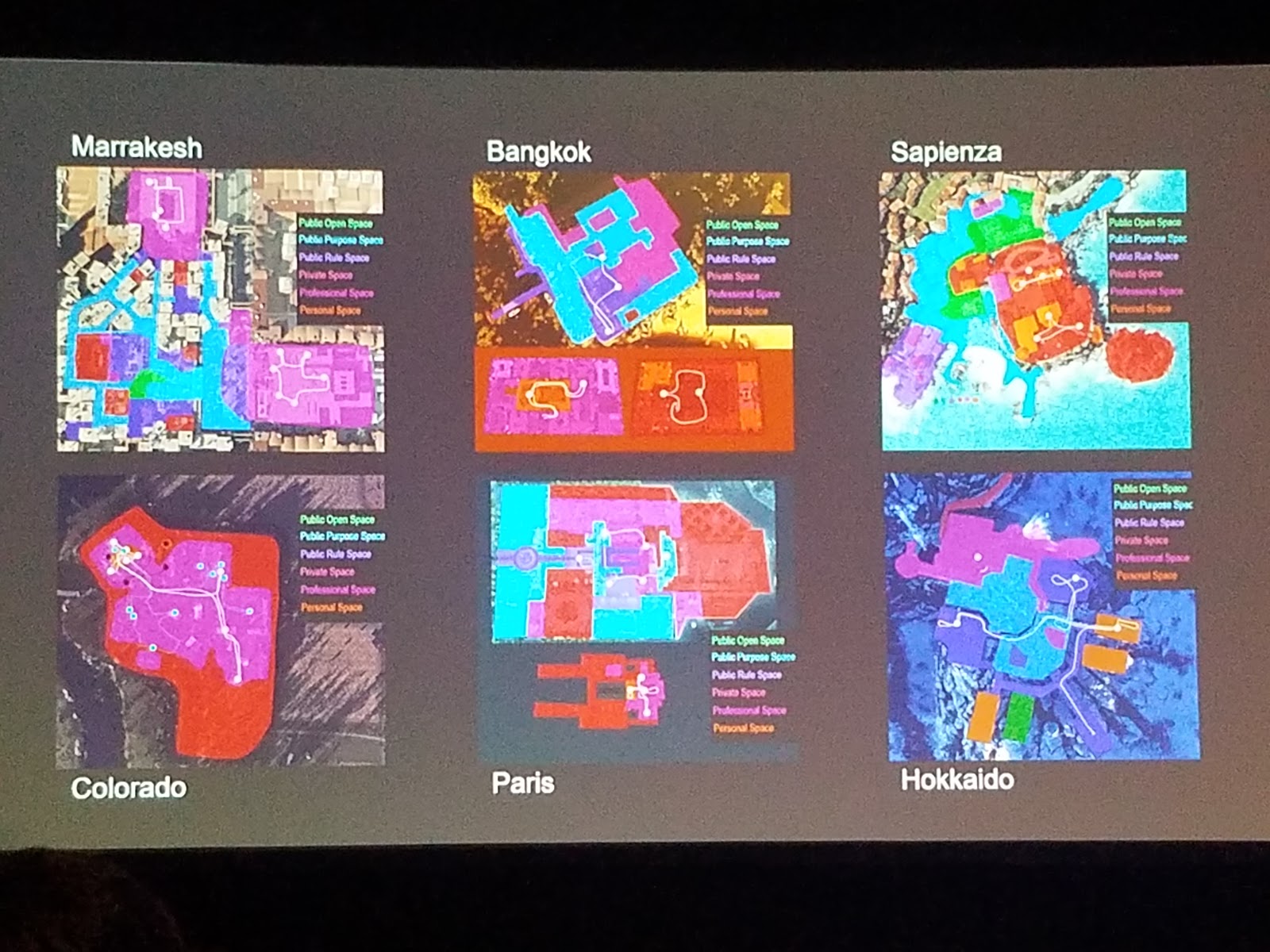

Andersen proceeded to break down the different sections of each Hitman 2016 and 2018 level into six categories: Public open space, public purpose space, public rule space, private space, professional space, and personal space.

You see the public open spaces usually at the start of each level. Agent 47 is minding his own business in a city square or walking down a public suburb road. These places generally don’t have any rules or restrictions, which allows the player to chill out long enough to get their bearings.

Public purpose places are still fairly rule-free, but they often present unique gameplay opportunities, like when that idiot Rocco is about to be late for his new job at the Sapienza mansion.

Public rule locations are like Sapienza’s ice cream shop, where the owner will get mad at you for walking behind the counter. Private spaces equate to Sapienza’s mansion and ruins, while professional spaces might include the morgue, where a disguise would be necessary.

Finally, a personal space often refers to one of the locations you might track a target to, somewhere they feel safe enough to be alone. These private spaces can feel like a proper “endgame,” whereas the vast majority of levels will try to always present players with multiple routes in and out. Think the decontamination lab below the Sapienza mansion, or Sylvia Caruso’s bedroom in the same level.

Andersen presented a number of interesting overhead maps of each level, segmenting all these levels into their various spaces, many of which rely on a sort of “snail house” flow. In Sapienza, the public spaces all connect into each other (or merge into public purpose spaces), but like any real world location, there’s various off-limits areas the further off the path you go. Allowing players to keep moving through an area without trouble goes a long way towards letting them figure out how they want to tackle an infiltration, Andersen said.

Andersen cited Hitman 2016’s Colorado as an example of these spaces fluctuating heavily in one direction. Colorado drops players immediately into the hostile territory of an anti-government terrorist compound, forcing 47 to play every move with greater care. Somewhat related, Hitman’s Colorado level also had the game’s lowest Metascore.

“It's interesting to see what happens when you take away half of our tools in making a Hitman level,” Andersen said. “We're only using half of the palette [in Colorado]. The way this looks from above is actually quite representative of how it feels to play. Everything is soldiers, this orchard they've taken over. It's hard to figure out if these soldiers are allowed here but not over there.”

When it came time to design Hitman 2, the team at IO wanted to explore more ways to keep players interested without having such huge space fluctuations between levels, where some can feel freeing and the others are overly oppressive.

“What we learned was that you can keep the player engaged without introducing trespassing,” Andersen said.

Andersen emphasized four big findings the team brought to Hitman 2, which mostly focused on the use of public spaces to free the player’s mind and get it running with possibilities. Hitman 2 players will notice that the size of public areas has increased (Mumbai and Miami stand out as great examples) and IO was careful to budget for those “backstage” areas that feature unique art assets, making the player feel like they’ve stumbled onto something meaningful.

“By using the whole ‘palette,’ it’s so much easier to create levels that feel more complex and varied,” Andersen said.

We would have to agree.

Joseph Knoop is a freelance writer specializing in all things Fortnite at PC Gamer. Master of Creative Codes and Fortnite's weekly missions, Joe's always ready with a scoop on Boba Fett or John Wick or whoever the hell is coming to Fortnite this week. It's with a mix of relief and disappointment that he hasn't yet become a Fortnite skin himself. There's always next season...