How the '90s family computer shaped a generation's exposure to PC gaming

Through my dad, the shared family PC introduced me to games and technology I'd never have found on my own.

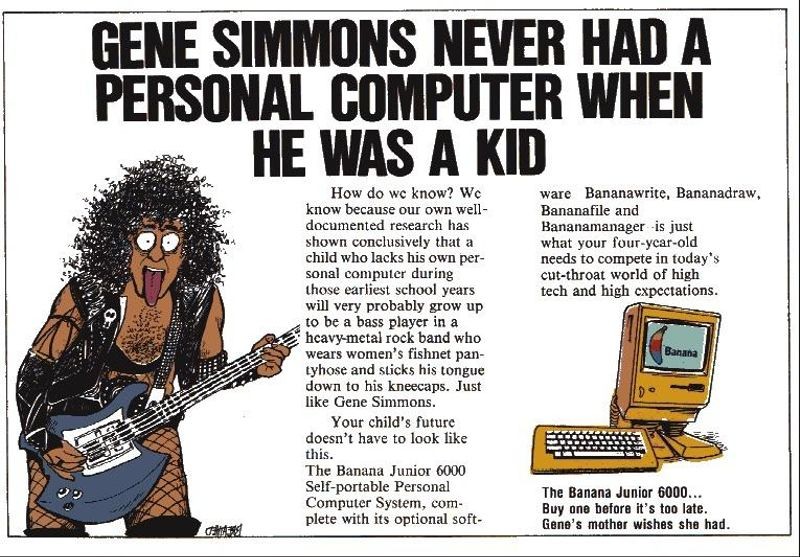

In 2009, as a young journalist, I got the opportunity to interview KISS bassist Gene Simmons. As I fretted over my questions ahead of the interview I dug out a yellowing paperback of Berke Breathed's comic Bloom County that had once belonged to my dad. In the world of Bloom County there's a fictional computer called the Banana Jr. 6000—a cheeky dig at Apple—and a glorious fake ad in which a cartoon Simmons gives it his full-tongued endorsement. When my interview was over, I timidly asked him to autograph my comic.

Simmons, wearing an unforgettable pair of lurid snakeskin boots, was tickled. "Of course I know about Bloom County," he smiled while signing the page. "Of course."

The home computer was a novelty, and an object of extravagance

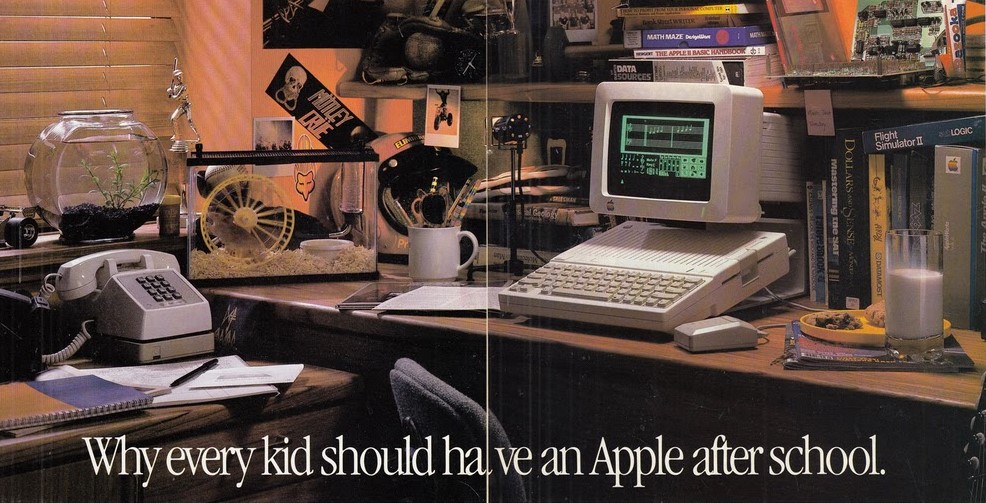

Most of Bloom County has nothing to do with computers, but it was part of my early introduction to technology through my father, a hobbyist who spent most of his free time in the "computer room" at the back of the house. His domain was a dim, narrow space stacked with parts, manuals, comics, CD-ROMs and floppy disks, and a Macintosh, immortalized in the Super Bowl XVIII 1984 commercial that aired the same year I was born.

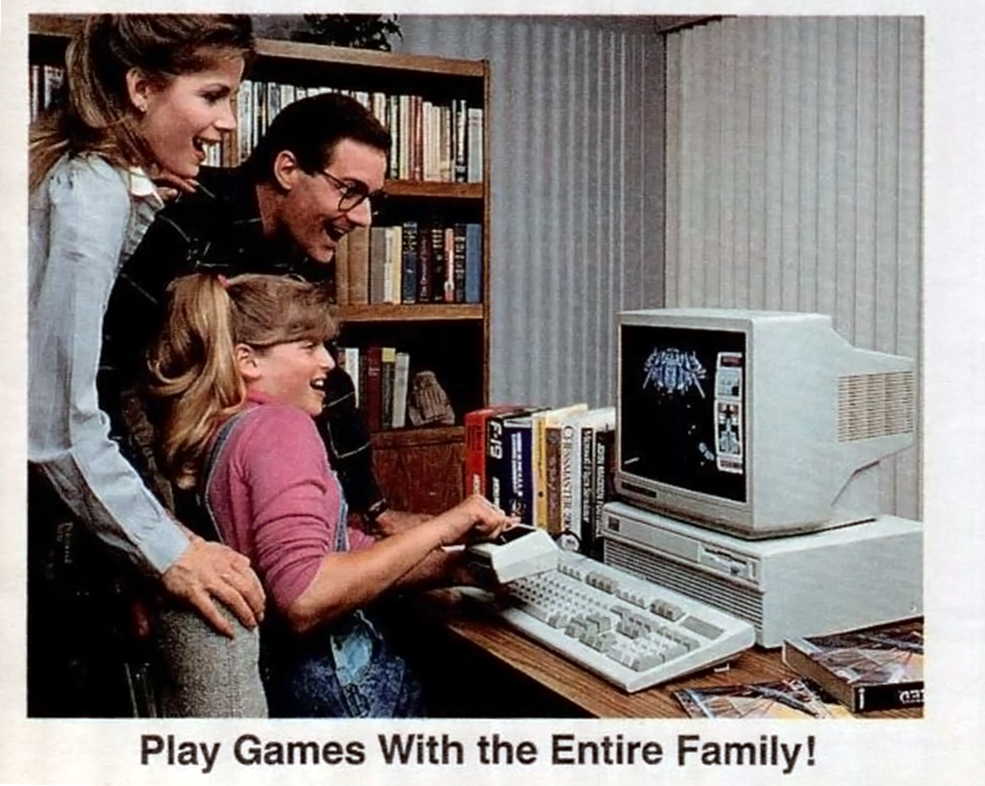

The Banana Jr. 6000 was part of the pop culture pastiche that defined my relationship to the family computer: at the time, the PC was a weird, occasionally temperamental friend that you had to learn to get along with. In the '90s the home computer was marketed as an equalizer, or at the very least, a must-have tool to prepare for the 21st century. The idea was to open up new possibilities and entertainments to middle-class families, and for a while, it was a singular point of access to a new cultural frontier. And on that frontier were games.

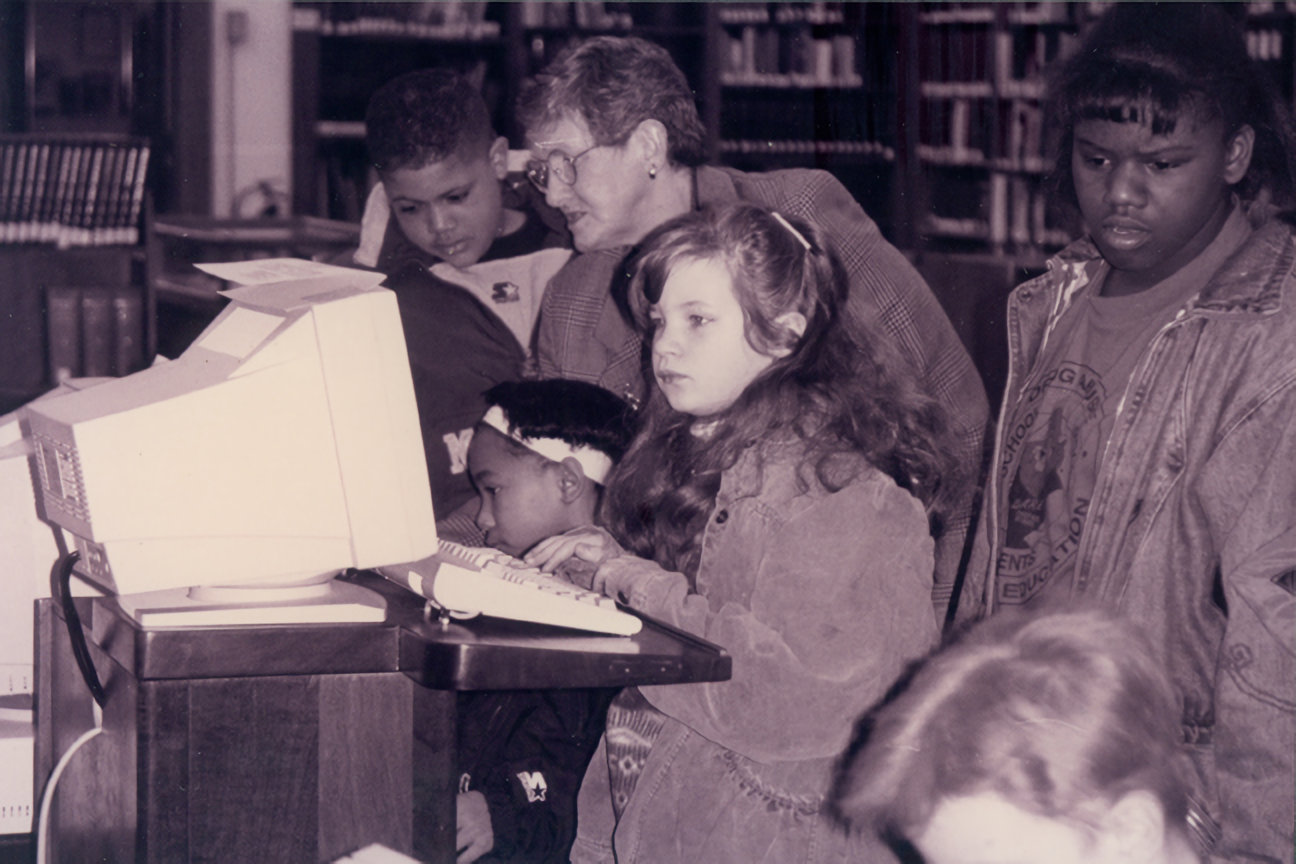

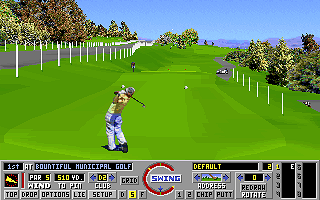

In historian Dr. Laine Nooney's words, "Gaming is the first form of computational technology most of us ever touched—the first time, in many cases, a computer was ever 'in our hands'." Home computers were mainly aimed at adult men of means, and my father became both game curator and gatekeeper, introducing me to the acerbic life sim Jones in the Fast Lane alongside the crusty white vibes of the Links golf series. Name a kid who actually enjoyed playing Links? (Because of sheer exposure: Me. I was that kid.)

Cable TV was still the heart of family hour, when you had to endure Family Ties reruns just to get to one fresh episode of The Simpsons. The home computer, though, was a different beast—a novelty and an object of extravagance. Unlike the communal hearth of the television, which gave everyone the same passive experience, the computer permitted only one into its realm at a time. Sure, you could watch someone else use it, but everything from the input mechanisms to the singular role of user made for a one-person experience that didn't really take spectators into account.

In the early '90s I was old enough to sit still in front of a monitor on my own. These were the days before broadband and Steam and today's ubiquitous personalization features. The computer was still an intimate experience for new users who were excited about games and the fabled information superhighway (or even just the static blare of the dial-up modem). For many people these were still baby times, and I was very much a baby user.

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

Confined to one shared machine, learning about games was a slow, osmotic process, watching and waiting for your turn at the monitor.

As one of the few kids in school with a computer, friends would come over to gawk at my dad playing Diablo. Sometimes he'd give them a go, and I seized every chance to explore Tristram myself. Crowding around to watch a grown-up face off against The Butcher was magical—an atmosphere of visceral terror among adolescent kids who were witnessing a legend for the first time. These are some of my fondest memories of the home computer, because it extended the bubble beyond my father and myself and I could be excited about games with people my age.

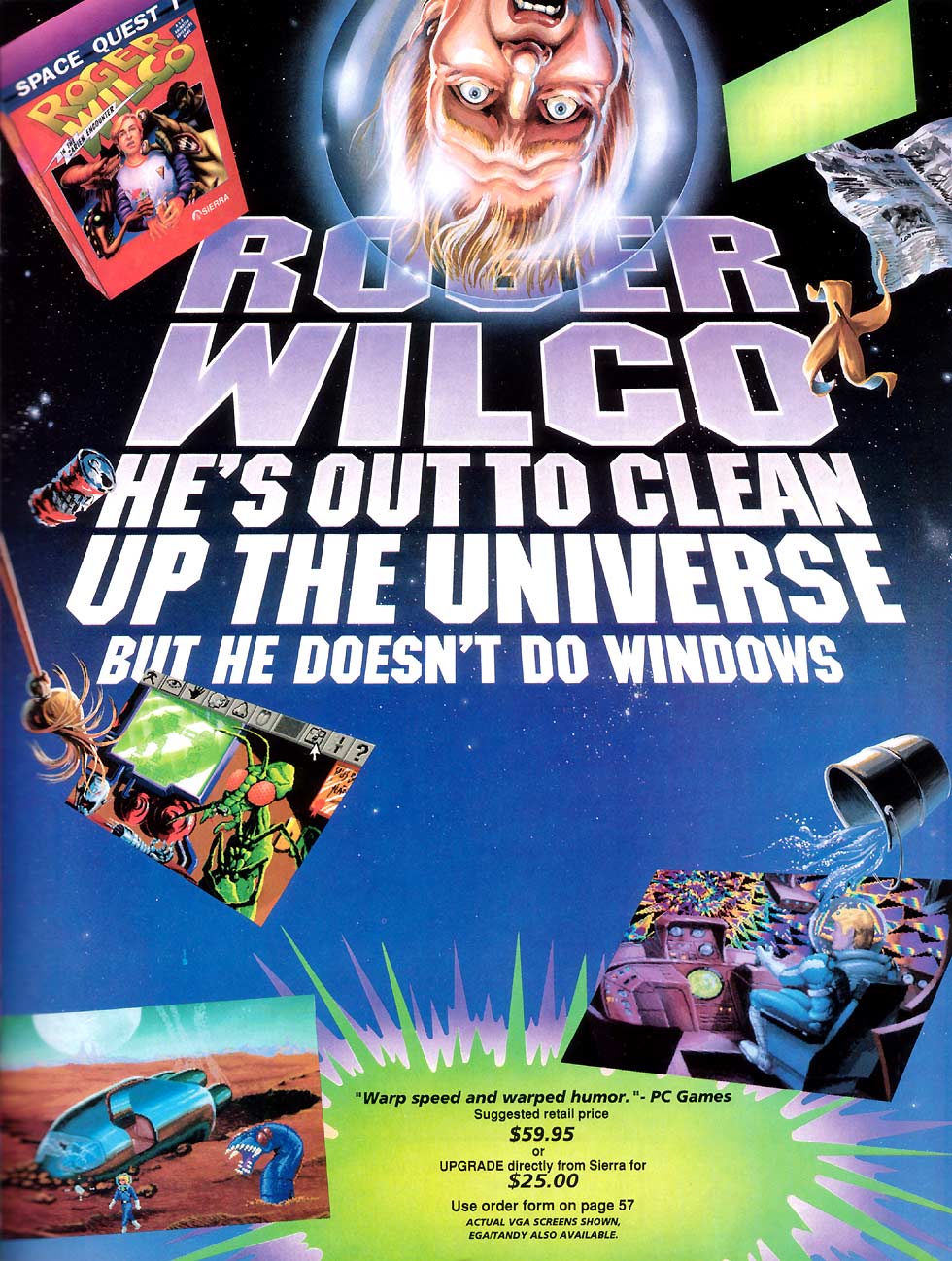

Before Diablo I'd mostly watched my dad play the non-raunchy parts of Space Quest. King's Quest and Day of the Tentacle became a conduit to his sense of humor—we tackled them side-by-side, co-op style. But to get valuable Space Quest time, I'd patiently watch him run 18 holes in Links or defrag a disk. I'd lurk in his computer room and soak things up like an annoying sponge. By spending so much time trying to follow my dad's journey through the personal computer age, his game paraphernalia took on a near-talismanic quality.

Copies of Leisure Suit Larry and fratty computer magazines were part of my technological coming-of-age. Subscription pages for internet service providers flanked painfully worded ads for male virility aids. At 10 years old I plowed through male pattern baldness advertorials so I could learn more about the ImagiNation Network, which allowed you to meet and play with real people online. But ImagiNation was only available in the US, and at the time, I lived in Singapore. "Meet new friends you didn't know you had when you share your interests and hobbies," purred its ad copy. Achieving peak gamer in the '90s wasn't just a classist comfort, but one that painted being American as a cornerstone of the ultimate gaming experience.

After a few years my mom and I inherited my dad's desktop hand-me-downs so my mom could learn CAD programs for her work and I could write bad stories on floppy disks. One of his biggest upgrades was a brand-new Gateway 2000, which arrived with much fanfare in the company's signature cow print packaging. As we gradually split off into our own separate bubbles, gender became another obvious division that defined the kind of leisure activities I was supposed to take seriously as a teenager.

Most computer programs and games at the time were a miserably gendered experience, which I tried to ignore. The Leisure Suit Larry series is the most obvious example of a "boys will be boys" romp that was actually more depressing than fun. But even point-and-click games with supposedly empowering female characters leaned on tired stereotypes of the sexy French maid (The Colonel’s Bequest), the damsel in distress (King’s Quest), and the bookish Asian shrew (Gabriel Knight). But beggars couldn’t be choosers.

Still, it was fascinating to see how computers were used in other homes—many friends' parents got them solely for accounting and balancing books, and games weren't really on the table. But going over and playing by house rules to use a friend’s family PC often told a larger story about how their parents viewed the computer. I quickly learned that while my dad was by far the most committed parent to PC culture, he was also the cagiest about sharing his knowledge. Other households, where the computer was treated more as an equalizer for everyone, had fewer rules and laxer punishments.

As old-school adventure and full-motion video games continue to resurface in new forms today, nostalgia for old technology has nudged me toward the realization that games are the only real lasting cultural legacy I inherited from my father. This goes far beyond genres, but the way in which I examine in-game objects, explore new environments, and even contemplate dialogue options. My relationship with games lives in a psychological landscape made up of my father's old desktop, the piles of CD-ROMs and magazines, the semi-drawn blinds, and the odd copy of Bloom County.

My own sense of cultural capital, coupled with the flawed instinct that older is more authentic, insists on associating these memories with a superior experience of technology.

It might not have been superior, but there was something powerful in the PC's scarcity bringing people together. Depending on your circumstances, gaming culture can be a very different animal, especially with today's much wider range of genres, subcultures, software, and hardware.The shared computer opened us up to experiences we couldn't have known to seek out in a way that's hard to replicate today, with the internet's infinite freedom and our individual devices. Personalized algorithms encourage our tastes to go deep rather than broad, showing us more of the things they already know we like.

It is, however, much easier to share in the joy of discovering a new game. For many today the idea of watching a friend play a game on a computer in person sounds endearingly quaint, especially when the same effect can be achieved remotely through Twitch or screen-sharing. Our devices today are smaller and more versatile than the desktop of old, but the sentimentality around sharing our experiences remains.

Perhaps what we've lost is a more intimate way of passing down cultural capital, even though the concept of having the "right" experiences with technology is problematic no matter the era. Desktop ownership in the '90s was a distinctly middle-class privilege that defined many a home and childhood. Who bought the games, and why? Who let you play the games, and did they play with you? Looking back at my precious allotted time on the computer, it’s bizarre to think I spent so much of it playing simulated golf, which I had zero real-life interest in.

Growing up at the peak era of FMV games has given me a deep well of sentimentality for grainy, cheesy game worlds that I never would have played without him. And while my dad and I don’t speak much, our shared history around the computer still affects my relationship with games today.

Today these roles are largely fulfilled by parental controls and algorithms, and the role of disseminating gaming culture has been dramatically reversed—it's no longer something for parents to gatekeep and curate, but an evolving world geared toward the young. This inversion has made it more difficult to bridge an ever-increasing generational gap. Thinking back to my moment with Gene Simmons, asking him to sign my Banana Jr. 6000 ad, it’s hard to imagine us having anything remotely in common, if not for the way pop culture cemented the home computer into our collective history.

Sentimentality around shared tech is on the way out, especially as devices become more affordable and accessible. There’s also the matter of cloud storage, digital downloads, and closed platforms, which deny us the tangibility of huddling around a primordial shared experience, and our ability to archive it. And while there remain many, many new ways of recording our evolving gaming history—memes, streams, and Discord culture are just a few—I can’t help but feel that we’ve reached the very end of an irreplaceable era.

Alexis Ong is a freelance culture journalist based in Singapore, mostly focused on games, science fiction, weird tech, and internet culture. For PC Gamer Alexis has flexed her skills in internet archeology by profiling the original streamer and taking us back to 1997's groundbreaking all-women Quake tournament. When she can get away with it she spends her days writing about FMV games and point-and-click adventures, somehow ranking every single Sierra adventure and living to tell the tale.

In past lives Alexis has been a music journalist, a West Hollywood gym owner, and a professional TV watcher. You can find her work on other sites including The Verge, The Washington Post, Eurogamer and Tor.