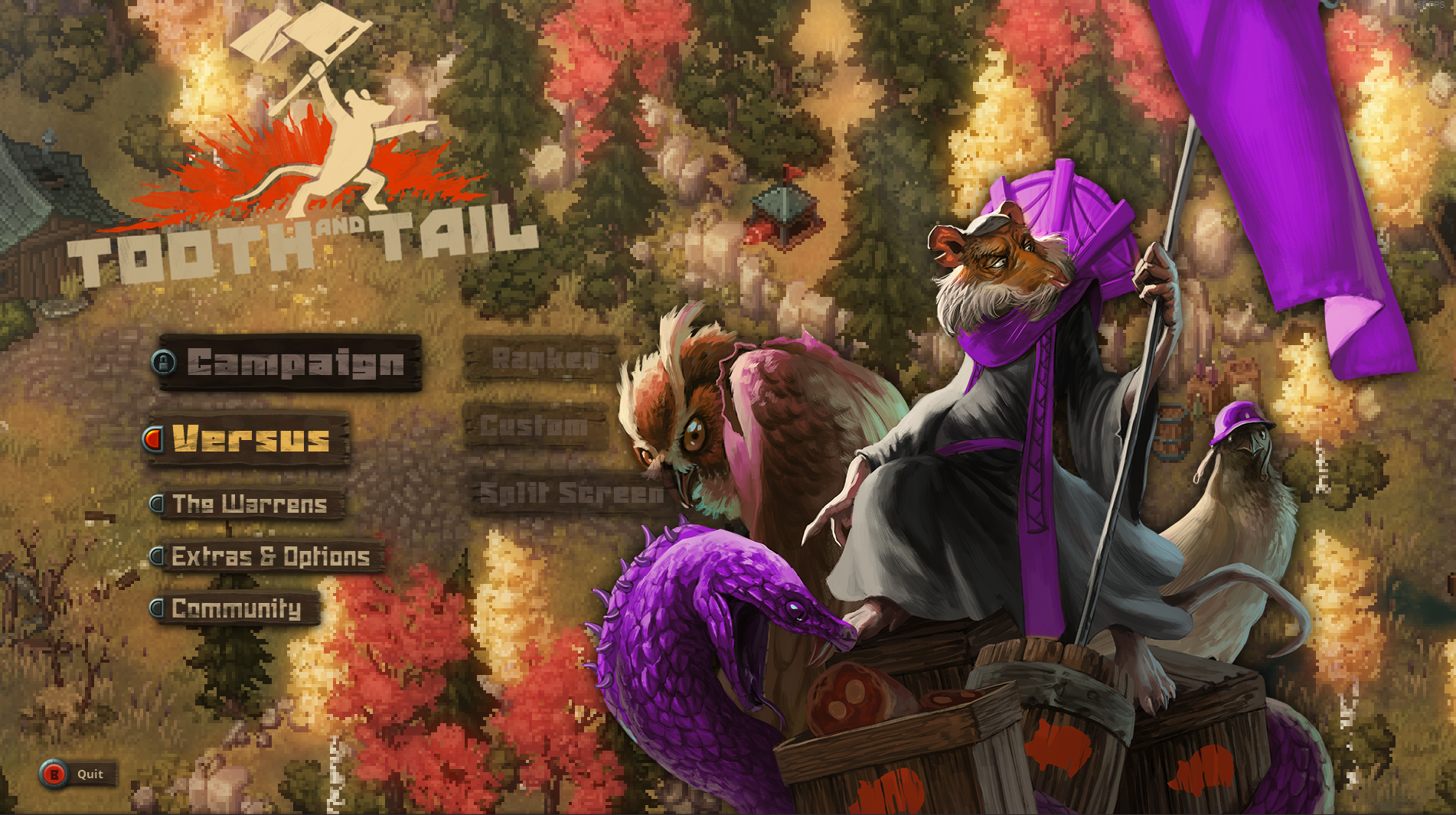

This guest post was written by Andy Schatz, creative director at Pocketwatch Games, who has an interesting take on authorial intent and work-in-progress games. Andy and Pocketwatch are responsible for arcade-style RTS Tooth and Tail, and you can follow Pocketwatch Games on Twitter at @PocketwatchG, or Andy at @AndySchatz.

Skyrim is your story, not Bethesda’s. The meaning behind Undertale is based on your choices as the player. The Witness is subject to your interpretation.

Videogames care not for the author’s intent. These games are yours. They were crafted as a single experience and released into the wild as complete, final products, subject to the player’s interpretation. Ever since French literary critic Roland Barthes wrote his 1967 essay “The Death of the Author,” Jon Blow doesn’t get to say shit about Braid’s true meaning. Braid is about me, my experience, it’s mine.

But Early Access and open betas have given power back to authorial intent. A huge number of our games, movies, and even books are now released as works-in-progress. And as long as a work is still being produced, the vision is still owned by the author. The best feedback we've received has been from players who keep our intentions in mind.

For two years, we ran a private alpha for our game-in-development, Tooth and Tail. My colleague Andy Nguyen carefully groomed an active community of around one hundred players, some of which have close to 1,000 hours in the game. If these players were strictly critics, they probably would have driven us crazy by now. But they aren’t just critics, they’re contributors.

The player-contributor typically recognizes that a game in progress is still being shaped by the author. Like sculptors, the longer an author works on a game, the more they expose the game’s true form. Player-contributors share that vision, and help to guide the author towards it.

Here’s one of our player-contributors (known as Shooflypi in our Discord channel), on a color change we made to one of our main characters:

The biggest gaming news, reviews and hardware deals

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

"Hi Andy, a few of us were discussing the Archimedes color change (from yellow to purple)... I remember you saying in one of the dev streams that you considered color to be an intrinsic part of each character like in Monaco. I think one of the reasons a lot of the Archimedes players are complaining about the color change (aside from not liking the new wine purplish red) is because it felt like it was a part of Archi's character. The new color is such a drastic shift that it feels like it completely changes his identity. I understand the motivations for the change and accept that they were probably necessary. Have you considered making Archimedes white? It would be distinct enough from the other colors and I think it fits rather well thematically with the clergy faction. It would also be much closer to the old yellow in feel.”

Ask any developer who has worked on an Early Access game: Players who “get it” are like gold. Shooflypi gets it. Players like this see both their personal experience and the author’s intent and help to bring those two visions closer together.

Players who understand the developer’s vision can also act as an emissary to the broader community of players. One Tooth and Tail player, YouthfulIdealism, often helps to explain our design philosophy to new players:

"Bardo: the game uses super few buttons, it’s not like it’s overwhelming to add 2 more. Besides left stick you are using only the triggers in combat.

"youthfulIdealism: Schatz hates hates hates adding more buttons...and I tend to agree"

YouthfulIdealism understands the design goal of Tooth and Tail because he asks questions like this:

"Actually, this raises an interesting question—how competitive should the game be?

"I've thus far seen it as a competitive game. Should it be a competitive-competitive game, or a casual game that can be played competitively, or—?

"...if it's supposed to be a completely casual game or a completely competitive one, I definitely need to adjust my viewpoint..."

The Overwatch scandal—you know, the one about Tracer’s butt?—had me cheered, not because of the sexual politics, but because the original forum post was couched in the language of authorial intent:

“What about this pose has anything to do with the character you’re building in tracer? It’s not fun, it’s not silly, it has nothing to do with being a fast elite killer. It just reduces tracer to another bland female sex symbol. We aren’t looking at a Widowmaker pose here, this isn’t a character who is in part defined by flaunting her sexuality.”

Regardless of the political argument, this poster was trying to make the game better by deepening and emphasizing Tracer’s character. Good developers kill for feedback like this!

Of course, when a game is available for purchase, the developer cedes some ground to players, regardless of whether the game is “done.” Red Hook Studios capitulated to fan backlash by adding an option to disable the Heart Attack mechanic in their hit RPG, Darkest Dungeon.

“We have been reluctant to add difficulty related options until now because focusing on our intended version of the game has been our number one priority and our experiments and changes during Early Access have all been in support of iterating on that. But it would be foolish for us to not consider the fact that the Darkest Dungeon community is now big enough to include diverse groups, some of which would like to play the game differently than we might have envisioned.”

Did the addition of this option make the game better? Or did it just silence critics? Darkest Dungeon was still a work-in-progress, but for sale as a complete product, which puts authorial intent and player experience at odds with one another.

The question of how creators should respond to fan feedback on works-in-progress becomes even more complicated when you consider that a huge amount of our media is franchised—the universe of Star Wars is essentially a giant work-in-progress. When George Lucas re-released the original trilogy, he treated his magnum opus as if it had been in Early Access all along. Did Han shoot first? It may make the storytelling less compelling, but the revised canon suggests he didn’t.

There’s a somewhat believable theory that Jar Jar Binks was originally supposed to be a Sith lord—to be revealed in Episode 2—but he was replaced by the forgettable Count Dooku after fans responded vehemently to Jar Jar’s portrayal in Episode 1. While most agree that the prequel trilogy was a trainwreck, it’s entirely possible that the magic in Lucas’ vision was muddied by being forced to respond to critics of his work-in-progress. Certainly, making Jar Jar a Sith Lord would have made the prequels even more memorable, unlike the practically fan-directed sequel, The Force Awakens. Good stories can be crowdsourced, but great stories are the product of a unique and singular vision.

When we get feedback on Tooth and Tail, some players tells us, “Make it more like Starcraft,” or “I liked Total Annihilation’s economic model.” Those players aren’t wrong, per se, they are just trying to make their own game. But we adore players who understand our design philosophy—minimal buttons, reduced micro, 5-12 minute matches, simple mechanics that become complex when they interact with one another—as those players tend to give feedback that strengthens rather than dilutes the vision of the game. If, as a player, you want to contribute positively to a work-in-progress, try first to understand the intent of the design. Then frame your feedback in support of that goal.

While players bear no responsibility to be contributors, so much of our media is now produced and released as works-in-progress that it’s worth respecting authorial intent when interacting with creators. Our games, our movies, our stories, are made more interesting when they are the product of an author, and supported by contributors who share that original vision.

The collective PC Gamer editorial team worked together to write this article. PC Gamer is the global authority on PC games—starting in 1993 with the magazine, and then in 2010 with this website you're currently reading. We have writers across the US, UK and Australia, who you can read about here.