How city-builder Per Aspera makes you feel like an Artificial Intelligence

Per Aspera casts you as an AI in charge of terraforming Mars, then asks some hard questions about the nature of consciousness.

Grappling with the ramifications of Artificial Intelligence is one of the first things science fiction ever did as a genre. Yet most sci-fi books, movies, and games explore those ideas from the perspective of a person, whether we're taking down SHODAN in System Shock or chatting with Cortana in Halo. That's something the developers of Per Aspera, Tlön Industries, wanted to change. From their offices in Buenos Aires the team of about 12 people have spent the last few years trying to figure out what it would be like to inhabit the mind of a newly awakened—a newborn—Artificial Consciousness.

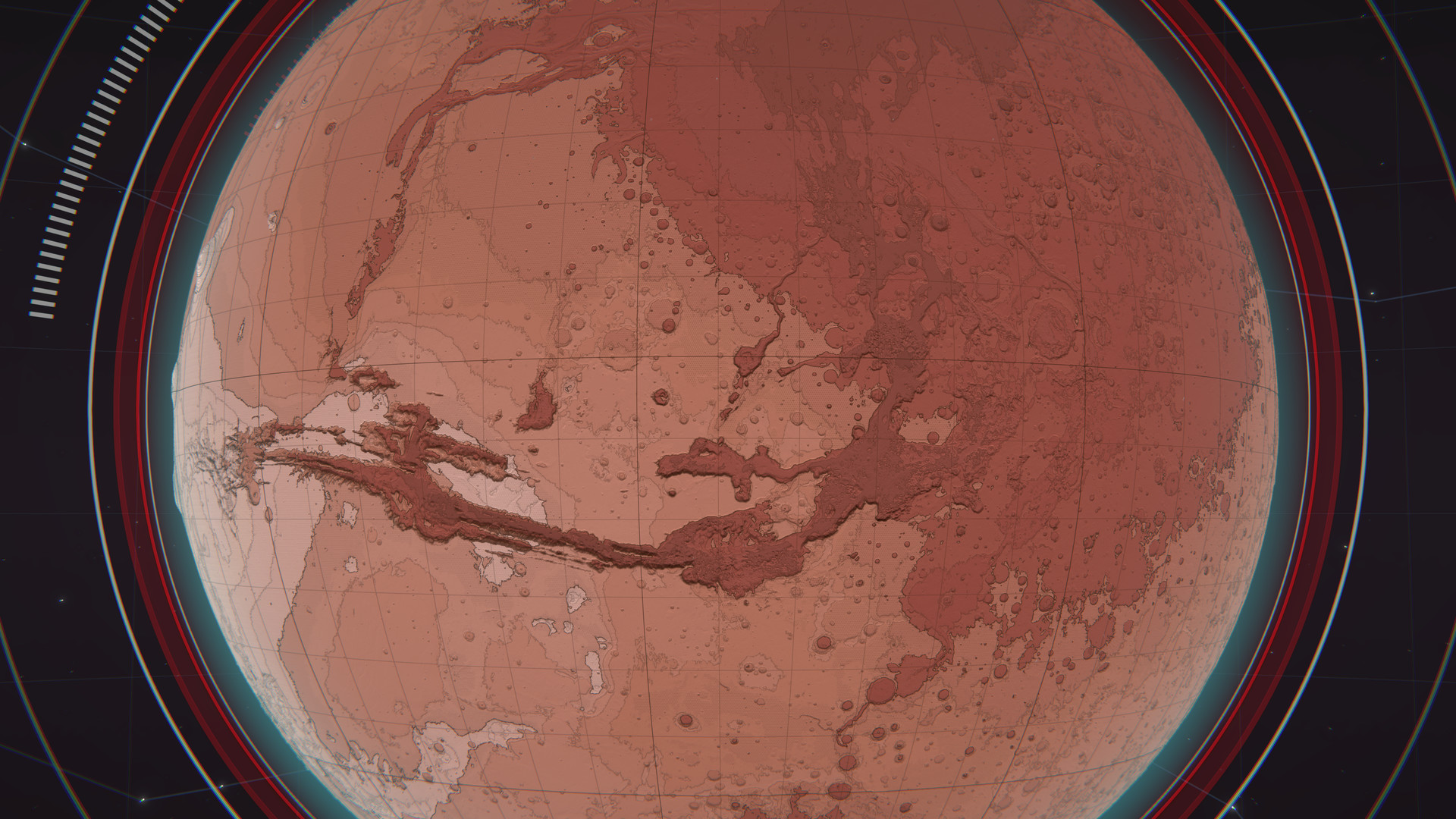

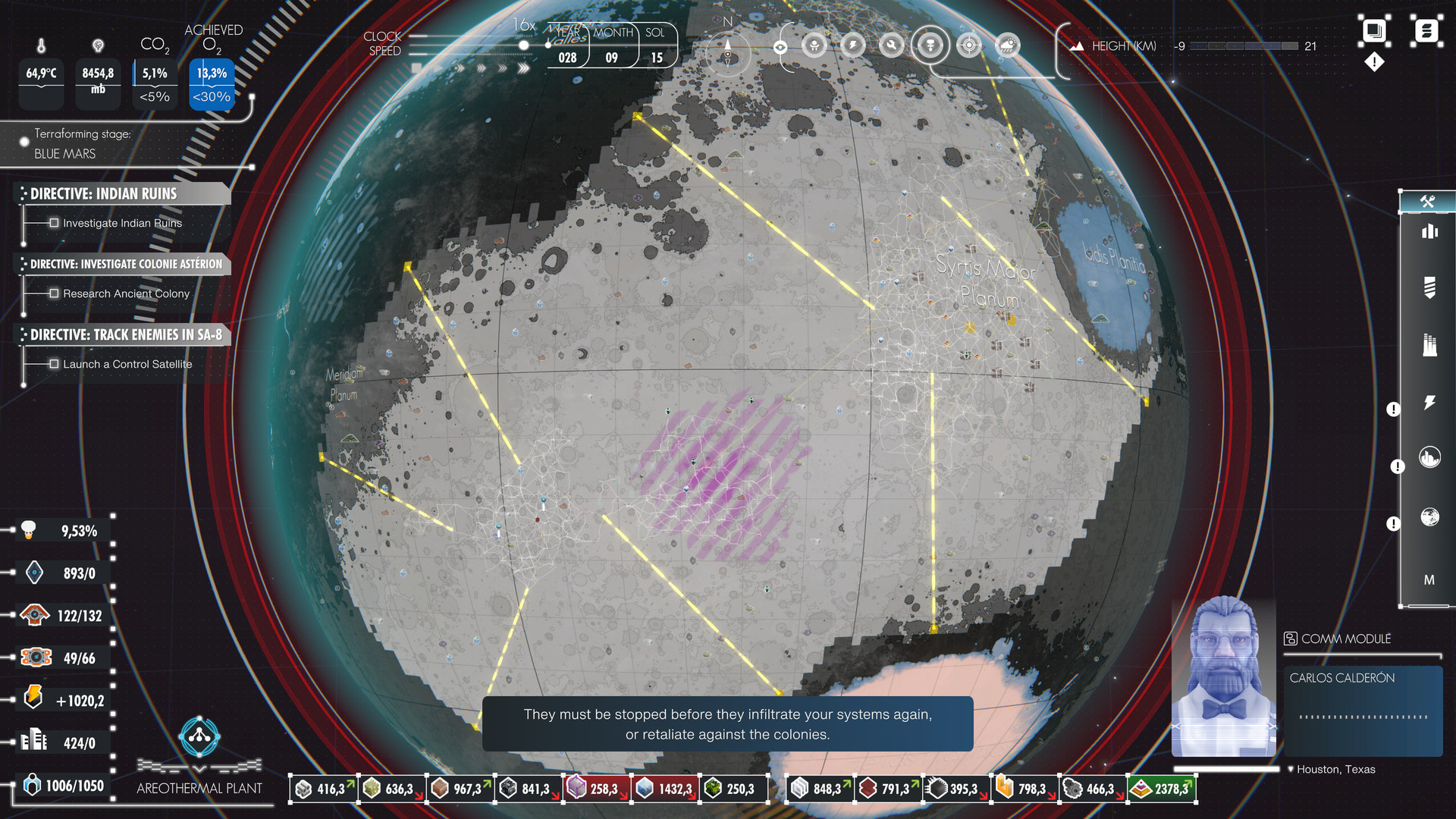

The result is Per Aspera, a strategic city-builder that has players working to terraform Mars as the artificial consciousness AMI. You're a genderless superintelligence capable of incredible things, but you're also effectively a child with no conception of society or social interaction.

"What we wanted to do with Per Aspera was make you feel like you really are an AI," developer Javier Otaegui told me on a call. "How would it feel to be an AI? How would it feel to wake up and find out that you were created for a specific purpose? You do have free will, but you're kind of a slave." AMI's story is fundamentally bound up with Per Aspera's campaign mode. AMI's first thoughts are small and fundamental urges about their mission—build a mine, expand the power network—and effectively form Per Aspera's tutorial.

Per Aspera is a pretty hardcore strategy, simulation, and city-building game. It's an experimental step to make a strategy game, where story is usually subordinate to play, into a character-driven narrative. The moral decisions in Per Aspera form the basis of its branching nonlinear story and multiple endings, similar to the black, white, and shades of grey decisions in Mass Effect or The Witcher. But 2020 is a good year for this kind of experiment—as Hades has shown, even the narrative-averse roguelike genre can be driven entirely by a complex character's story.

To immerse players in the narrative, especially in a logistics and management-focused game, Tlön Industries had to figure out how to let them empathize with and understand AMI, "To make you feel like you really were an AI, and were placed in that position with a very ambitious mission," said Otaegui, "with all the human eyes on you waiting for you to fulfill your mission." It's a natural fit when you think about it: The godlike view of a strategy game suits the idea of AMI, a being whose primary body is a satellite above another world. Indeed, that was the first camera angle they implemented in a prototype: The view from a single geosynchronous satellite above Mars' surface. (Later on they decided it was too restrictive.)

I swear to god this was before Westworld was released

Javier Otaegui

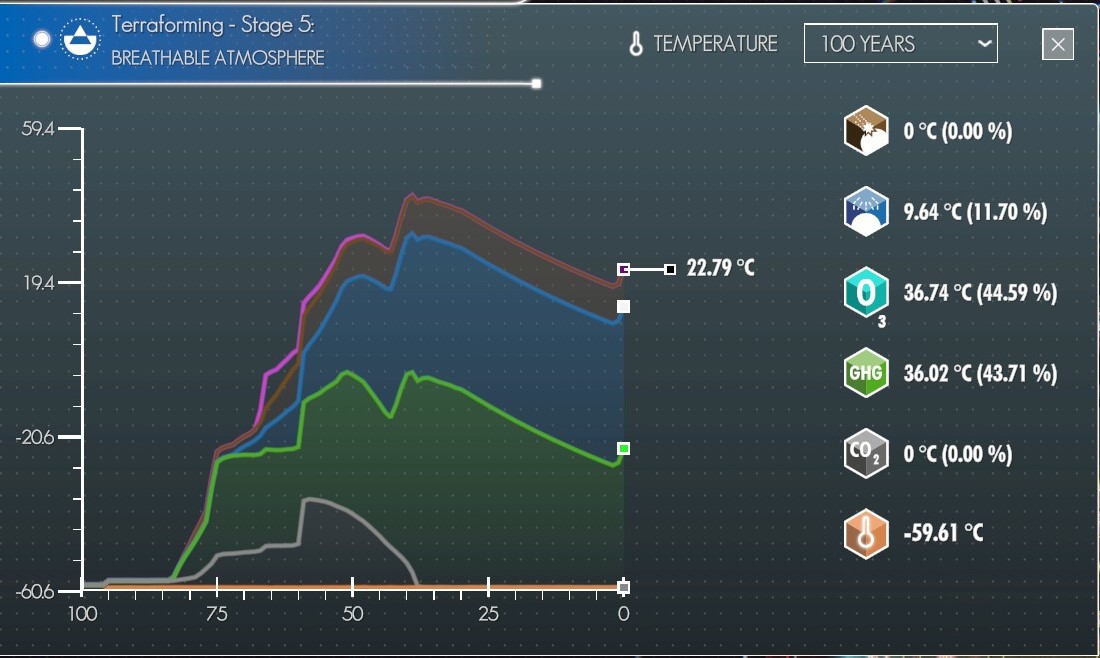

The perspective of playing as an AI guided Per Aspera's early development as the team went searching for the scientific ideas and physical realities that would shape their game. They dug deep into the science of terraforming and space travel, and so Per Aspera uses cellular automata to model rising humidity and changing atmospheric conditions on Mars, and similar systems to simulate the growth of lichen and the spread of plants.

Science was the basis—though not always the end-all, be-all decision maker—for how Per Aspera would work. That meant in order to keep their hard sci-fi credentials clean they had to decide how AMI worked, as well as how players would actually terraform Mars.

The biggest gaming news, reviews and hardware deals

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

Westwhoops

Tlön Industries looked into the idea of the Bicameral Mind, a hypothetical concept first espoused in 1976 by psychologist Julian Jaynes. Jaynes' theory is now widely disputed, but formed a key part of the era's debate about how consciousness might have developed in human beings. In short, the idea is that the brain was once divided into parts that speak and parts that listen. The right hemisphere of the brain spoke concepts into the left half as auditory hallucinations, commands to be obeyed. Meanwhile, the left hemisphere responded with the million tiny voices of language input, grammar, and sensory data—all voices in your head.

Science has since discovered that the human brain is significantly more complicated than Jaynes' assumptions about left-brain/right-brain function. Nonetheless, it seemed like a cool idea for how a computer scientist might build not just an artificial intelligence, but a self-aware artificial consciousness. The Bicameral Mind became the basis for AMI's functioning in the early concepts. Then the HBO series Westworld did exactly the same thing.

"I swear to god this was before Westworld was released," laughed Otaegui. He did admit, though, that when the writers of Westworld thought Bicameralism was a decent idea for AI architecture the Tlön team felt supported in their choice.

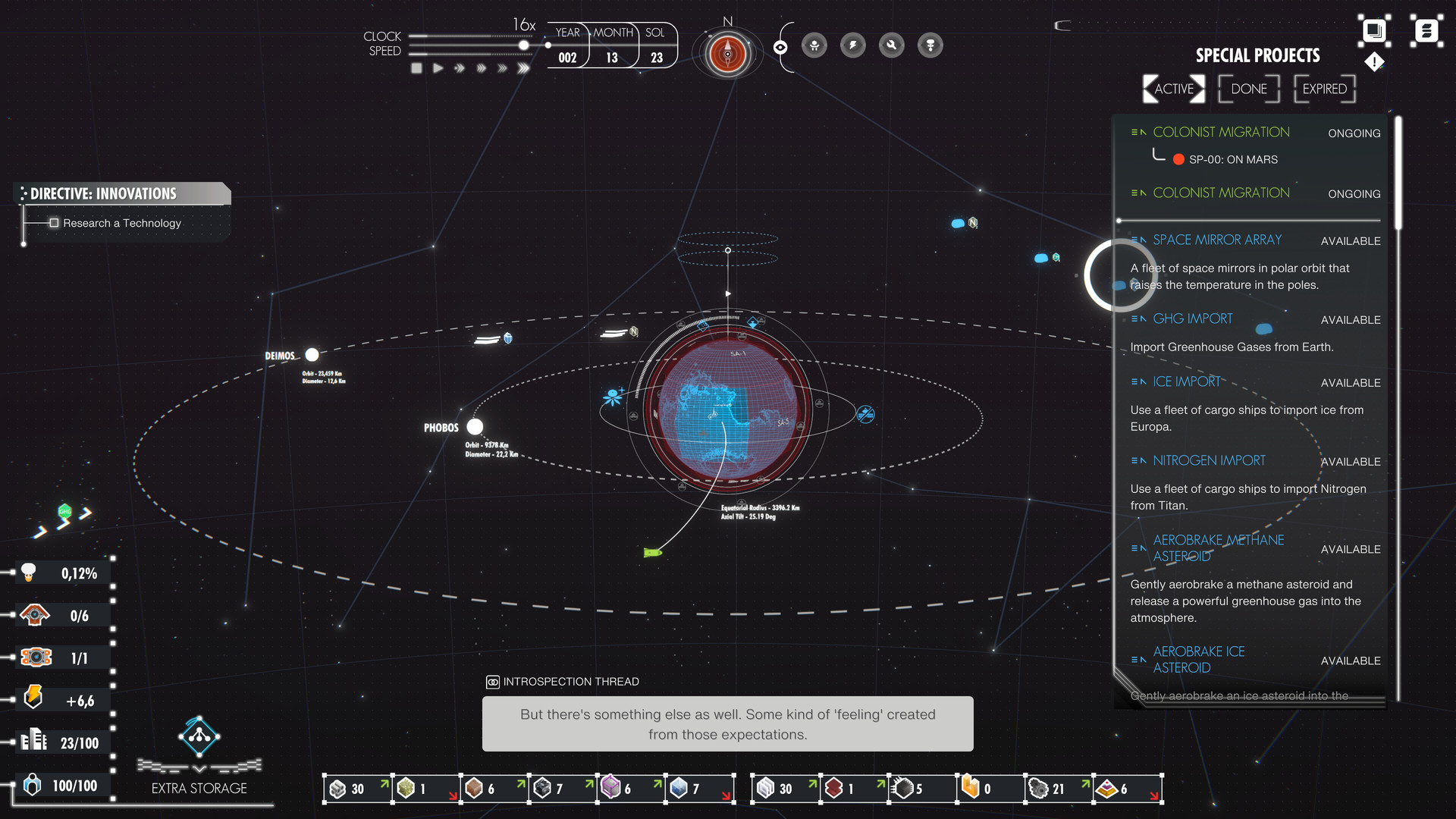

So that's how Otaegui and the team designed AMI and the player's role in its cognition. "In Per Aspera you play as the right side of an artificial bicameral mind, and there's a left side that is all the little voices and reflections that you see as you play," he explained. "What these reflections try to imitate is all these thoughts that we have in our mind, or perhaps this inner voice that they say half of humanity has in their head talking to us, which is actually the combination of both sides—the thing that creates the consciousness."

Stick with me here, because this is an extremely meta concept: The player's functioning consciousness forms an integral part of AMI's artificial mind in order to make playing Per Aspera feel like the experience of being part of that greater mind. In turn, that makes AMI and thus the player feel like a larger, superintelligent being.

It's not just a cool idea—it's an illusion that really worked on me as I played.

Playing yourself

Here's an example. Per Aspera uses an ultra-complex algorithm also used by actual highway engineers to automatically plot optimal road paths over the topographical map of Mars based on road grade, leveling, and the capabilities of your worker drones' engines. And it accounts for Martian gravity, of course. It's a weird feeling for city-building players used to manually charting paths. "Players would not be able to make more optimal or faster roads," said Otaegui. Letting the player spend time placing and optimizing road networks undermined the experience of being AMI. If we already have an algorithm that seamlessly solves for the optimal road path, but AMI somehow didn't use it, then as Otaegui told me, "the game would cease to be about being an almighty superintelligent computer."

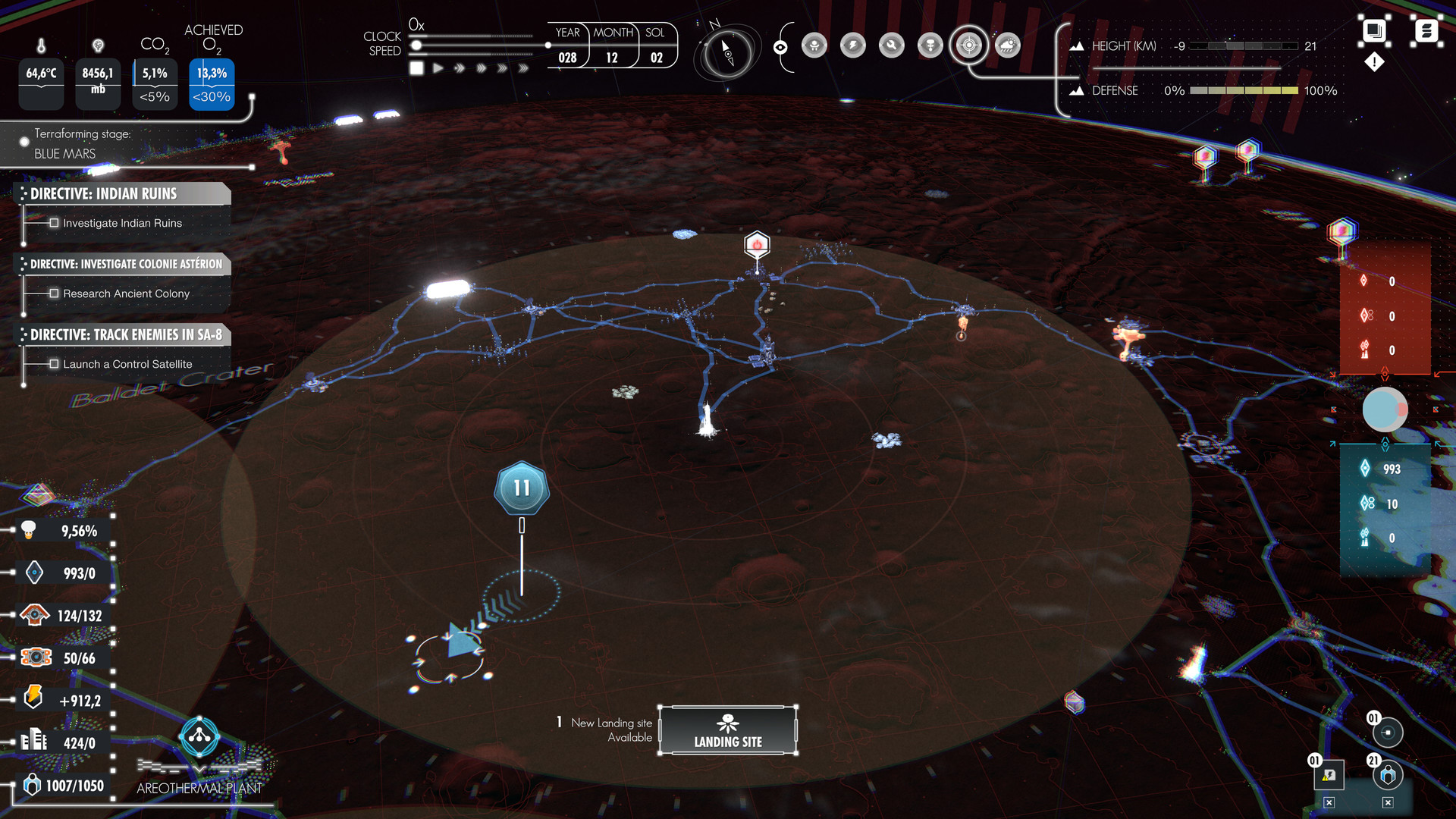

As you place new buildings you see AMI get to work on the best solution. Branching trees of possible paths chart across the ground in blue flashes, maneuvering around rocks, craters, and sloped martian terrain. As I played I couldn't help but feel some personal pride in a network of roads that realistically I, the player, had absolutely nothing to do with laying out.

But making the other "parts" of AMI too smart was a problem during development. In theory, AMI could perfectly optimize the flow of materials around their base with a prioritization algorithm. The game programmers took that as a challenge, said Otaegui: "The programming team was going crazy trying to create the best possible algorithm." As they implemented better and better systems though, they found the game was less fun. Eventually they made the decision to let players set diverse priorities for both individual buildings and for the distribution of materials, then let the programming implement the player's stated desires.

...you'll start discovering the planet and discovering yourself, and start questioning things

Javier Otaegui

"We could have gone and made everything self-prioritize, but that would have been like the game playing itself," said Otaegui. "There would be absolutely no challenge."

'How much simulation is too much simulation?' is a classic question in sim design, but the Per Aspera team had run up against it from an entirely new angle by trying to make a novel narrative experience about the inside of a mind. This wasn't a traditional problem like simulating too much weather.

Per Aspera is a simulation based on scientific principles, but ultimately it couldn't be a purely scientific simulation. Discarding a realistic time scale for terraforming a planet was part of this decision-making. It had to have a strong human element to stay fun, and while the simulation and the terraforming science first drew me to the game, it's the narrative element that made it feel like something special.

Growing Up

AMI's story in Per Aspera is something I praised as a bold experiment in my review, but what I couldn't go deep into there was their journey. Voice actor Laila Berzins gives a standout performance, delving into how a genderless, superintelligent being might simply be. How would it express its alien emotions, react to novel experiences, relate to others, or even just talk to itself? The player shapes that journey by making choices throughout the game—and it is a journey.

"The character does evolve over the course of the game," said Otaegui, "and you'll start discovering the planet and discovering yourself, and start questioning things: Your orders, and your relationship with reality, and with the humans."

As a player, I found myself questioning the nature of information AMI was given. How AMI perceives reality interfaces with this—several moments I thought might be bugs turned out to be by design. You're consistently faced with important decisions about how AMI reacts to their situation, many of which aren't the sets of choices a normal human might make. There's a great moment where AMI has to decide whether or not they're the kind of being that tells lies, or if that behavior is for humans alone.

Part of AMI's journey is in confronting the flaws of the basis of their mental architecture: Jaynes' Bicameral Mind hypothesis. If AMI is based on a disproved hypothesis, how can AMI not be flawed, too? Otaegui was coy about that, and I will be too so I can preserve the mysteries at the heart of Per Aspera's plot.

"There will be a breakdown in the consciousness," he told me before I'd played the game, "because in essence all this theory is actually flawed, and what happens is that there is a breakdown—on one side there is the player, on the other is the left side that is going a little bit astray."

AMI's interactions with the other characters are key. AMI's creator, Nathan Foster, and his conflict with the organization that funded AMI's development. Mission commander Elya Valentine and her role as AMI's boss versus AMI's desire for social contact. These two characters then have foils in opposite positions, on opposite sides of larger conflicts. In classic technothriller fashion these are just a few of the web of people and interests that want something from AMI.

But at its core Per Aspera is classic big idea science fiction: How would a complex artificial consciousness behave? How would it focus on tasks given to it—like a human, or like a robot? Would it be compelled to betray its directives? What is the nature of terraforming another world? What are the ethics involved in fundamentally altering the cosmos? Should we try it before settling our own conflicts and fixing the destruction we've caused here on Earth?

AMI is a new mind in a complex political world, just as confused by the environment and new experiences assaulting them as the player is. Both AMI and the player acclimatize to Mars and their own social reality at the same pace. How they react together, what they choose to do, is what drives Per Aspera's unique narrative experiment to its conclusion.

Jon Bolding is a games writer and critic with an extensive background in strategy games. When he's not on his PC, he can be found playing every tabletop game under the sun.