How modders are helping everyone play games

From UI tweaks to difficulty overhauls, mods have made PC gaming more accessible.

This feature is part of PC Gamer's Accessibility Week, running from August 16, where we're exploring accessible games, hardware, mods and more.

Amid the countless mods that thrust Thomas the Tank Engine into unrelated games or change a character's appearance—I'll never be able to unsee Resident Evil 2's Mr. X in a thong—are crucial tools that mean the difference between enjoying a game and hardly being able to play it at all. Though more and more developers are considering the needs of disabled gamers, and accessibility more broadly, there are still plenty of instances where even studios with vast resources drop the ball. That's where the modders come in.

While PCs can be complicated bits of kit, there are lots of accessibility benefits inherent in the platform. "PC is the golden standard for what right now can be considered accessible," Steven Spohn tells me. Spohn is a major accessibility advocate and COO of AbleGamers, a charity that seeks to improve the lives of people with disabilities through gaming. He adds that it's through the adaptations it can offer that it has an edge over consoles, and that includes its potential for modding.

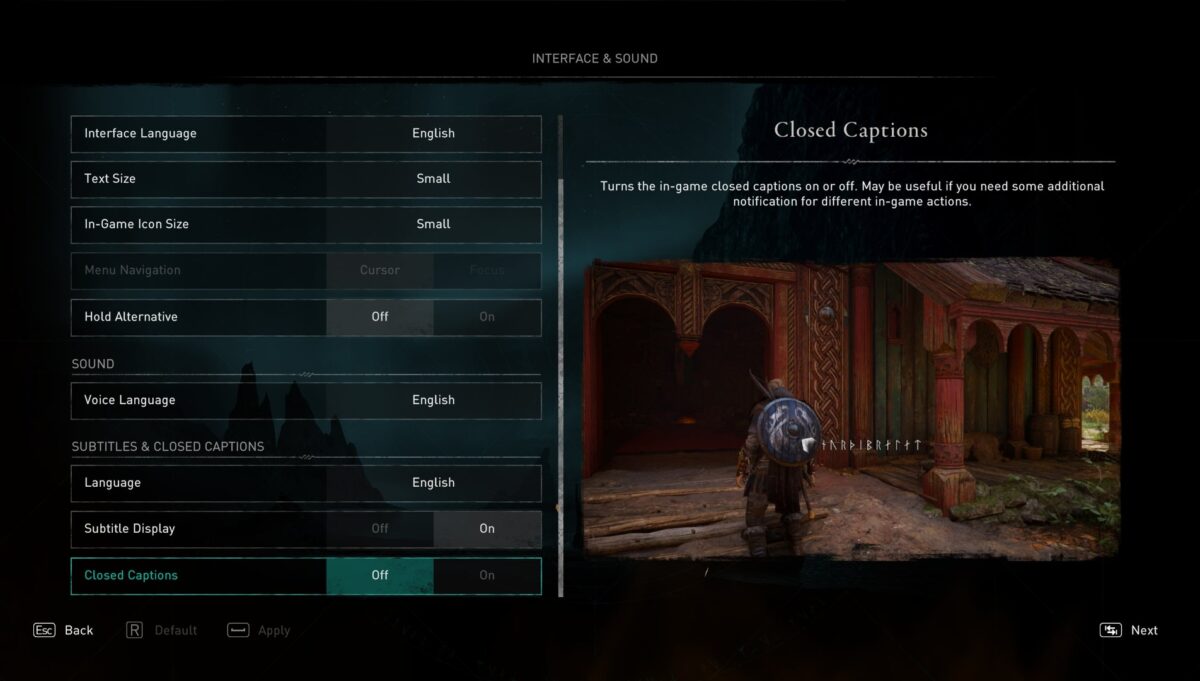

For every game that dedicates a whole menu to accessibility options, there are a multitude that don't even have the basics. One of the most common issues is text size, with far too many games expecting you to have a magnifying glass on hand before doing a spot of reading. It becomes even more of an issue if you try to play a PC game using a TV. Being able to change the UI or text scale is crucial, but the feature is often overlooked.

UI and text tweak mods are extremely common as a result, with modders picking up the slack. They're often among the most popular mods, too, as they correct an issue that affects a broad set of players. Field of view mods are similarly common, as even some modern first-person games omit the option. This is further complicated by developers choosing to have a restrictive FOV for aesthetic reasons, or to maintain a claustrophobic atmosphere.

"PC is the golden standard for what right now can be considered accessible."

Steven Spohn, AbleGamers

On Nexus Mods, one of the most prominent Resident Evil Village mods adjusts to the FOV. Lazy FoV And Vignette Fix gives players sliders to change these features in real-time, reducing the threat of motion sickness. Modder Mace ya face doesn't mince words in the description: "Hello all! Capcom has done it again. Another first person Resident Evil game with a locked FoV and vignette coverage. One imagines they'll trot out the same insane nonsense as last time about it being more spook when you're getting motion sickness. So I wrote a tool to fix it."

I wince whenever I see the word "lazy" used in regards to developers, but it is bewildering to see a big, expensive first-person game without this fairly basic feature. And the comments players have left show how essential it is. "First person games typically give me motion sickness after a short time playing, but somehow altering the FoV is preventing it," writes one user. "I'm so happy this mod exists. I had problems paying RE7 sometimes due to motion sickness, and this will probably help a lot," writes another.

Because issues with FOV and text size affect so many people, it's a lot easier to find mods that fix these problems. Often these mods aren't explicitly designed for disabled gamers, like Here's What You're Looking At (hwyla), a Minecraft mod that provides text descriptions for the game's many very similar blocks, but they still open the game up to people who might otherwise have had no way to play. Mods created specifically with disabled gamers in mind aren't as numerous, but there are still modders tinkering away to change this.

The biggest gaming news, reviews and hardware deals

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

Screen reader mods are becoming more commonplace, for instance, like the punny Say the Spire and Text the Spire mods for, obviously, Slay the Spire. The latter was designed by Wensber to help their partner play, but also highlights an issue with relying on modders for these important additions. On Reddit, the modder explained that the "documentation is probably shit as only my girlfriend is using this and I just explained it all to her". In this instance, users reported that the documentation was fine, but it's a reminder of the extra steps involved in using mods, making them potentially tricky to use.

While a lot of mods focus on legibility, gamers have a lot of different accessibility needs. Developers aren't necessarily being ableist when they create obstacles for disabled gamers; they simply might not recognise how certain features or limitations make it impossible for some people to even play the game.

"Mouse sensitivity and camera movement are extremely important to me personally, because I am somebody with SMA," Spohn explains. "I can only move my mouse about a quarter of an inch across the table in a square. And I have to have my DPI up at 16,000, which is just such a high rate that most people couldn't even control it on that speed. And in order to play video games, sometimes that's not even enough, I need the game to have increased accessibility or increased speed."

Games sometimes limit the DPI, however, which stops Spohn from being able to play. Guild Wars 2 is one example, so when ArenaNet asked how it could improve the MMO's accessibility, Spohn recommended they change the DPI cap. Unfortunately, in this case, becoming informed didn't inspire ArenaNet to act. It used "ambience" of all things to excuse the cap. This is why modders are so crucial. When the same issue cropped up in Final Fantasy 14, Spohn found a mod already existed that reduced the mouse sensitivity, which meant increasing it was also possible.

"So I sent them a message that said, 'Hey, can you reverse this and make it faster?' And they were like, 'I don't know why you'd want that, but yeah,' and then I explained and they were like, 'Oh yeah, cool.' And within three hours, I had a little mod that sits outside of the game, and it just turns up the mouse sensitivity. That's all it does. And that's super cool, that a community exists where they can just help you like that for free, out of the goodness of their heart—and very quickly at that."

Games that require a lot of precision, or punish mistakes, can also be impenetrable, but they don't have to be. Inspired by Celeste's official assist mode, Cuphead's assist mode mod alters the difficulty of the notoriously tricky game by giving players more HP, increasing damage and doling out more coins. Sekiro The Easy does something similar to Sekiro: Shadows Die Twice.

Mods that make tough games more accessible are sometimes greeted with the same vitriol as requests for games like Sekiro to get difficulty modes. There are arguments about maintaining a developer's artistic vision, or they'll give examples of disabled gamers who were able to complete the game without assistance (which is unhelpful, given the wide range of disabilities that make gaming a challenge), and all of them just sound like gatekeeping.

The two things are often conflated, but disabled gamers aren't necessarily asking for games to be easier, as Rachel discusses in her recent article on accessibility and difficulty. The issue is what makes them challenging, and the unintended obstacles that can arise from this. There is absolutely nothing wrong with a soulslike having difficulty modes, but that's not the only solution. E-Kon's Easy Mode and Accessibility Options, also for Sekiro, takes this into account. The mod is split into two parts, with an easy mode for people who simply don't want to be battered over and over again, and then a separate set of accessibility options.

"There's an assumption that just because someone is disabled, they must be bad at games," E-Kon says. "So games have to be made easier for them. That's a really bad way to approach designing for accessibility. Here, I've done my best to try and focus on what specifically might prevent colourblind people from enjoying the game, or unintended difficulty and barriers getting in their way. And I tried to change it in a way that doesn't affect the core gameplay."

While accessibility isn't just about adding easy modes, they shouldn't be dismissed. They certainly still make games more accessible, and Spohn argues that reducing the difficulty for people who need it, whether it's through mods or an official mode, does not affect the core of the game.

"No one in the world," he says, "including myself, who's one of the most vocal people about easy modes, is saying, 'Don't add a hard mode. Don't add an extra hard mode.' All we're saying is there needs to be a spectrum of easy and medium and hard and extra hard and super oh my god I'll never beat this. Like you can have multiple difficulties in a game and it doesn't lose anything. And I've got huge developers, like Cory [Barlog], responsible for God of War, who have said repeatedly 'Accessibility does not impede on my vision for a game.' But some gamers will not hear that."

One benefit of mods is that it sidesteps the arguments about what the developer's vision is—or at least it should. Some people like to argue regardless. But when a developer includes mod support, or simply allows their game to be modded, that becomes part of their vision, inviting players to make changes and tailor the game for whoever they want. I don't think Capcom envisioned Mr. X in a thong, but nobody was up in arms about that. And if you don't want to see his muscular cheeks, don't download something that lets you do that.

"And that's super cool, that a community exists where they can just help you like that for free, out of the goodness of their heart."

Steven Spohn, AbleGamers

Mods have given us some brilliant experiences and fixed utterly broken games, but for disabled gamers the real benefit is parity. "Let me play the game" is all they are asking. So it's incredibly reassuring to see modders rise to this challenge. And they do it in their own time for free. Remember that when a developer says it doesn't have the resources to include accessibility features. Even a tiny team has more resources than most modders. The problem is that sometimes these things are afterthoughts, but if accessibility is considered right at the start of development, then resources can be set aside to make sure all the boxes are ticked.

We're lucky to have all these passionate modders working away to make games more inclusive, but as much as they are a positive influence, it shouldn't fall to the fans to correct the oversights of developers—especially when they aren't being compensated.

"It is both a solution and not a solution at the same time," says Spohn. "It is a solution in the same way that I can take a whole bunch of Gorilla Tape and tape a hole in the side of my house, and it will hold, but it's not exactly the way that that product was meant to be used in the first place. And you have to be careful in a subject like this, because you don't want to condescend to the modders, because they're amazing, and if it wasn't for them some things would not be accessible at all… Yes, I think it's fantastic that modders are taking up the charge; I just think that any conversation like this would be a disservice to not mention that it's sad, in this day and age, that there has to be modders."

Until accessibility becomes ubiquitous—a direction it thankfully seems to be going in—these mods will be a necessity. Eventually they might not be required, and the modders can then go back to putting monsters in tiny pants, but for the time being it's good to know that they're out there, adding colourblind options, giving you more HP, fixing the FOV and doing the hundreds of other things that make it easier for everyone to enjoy these games.

Fraser is the UK online editor and has actually met The Internet in person. With over a decade of experience, he's been around the block a few times, serving as a freelancer, news editor and prolific reviewer. Strategy games have been a 30-year-long obsession, from tiny RTSs to sprawling political sims, and he never turns down the chance to rave about Total War or Crusader Kings. He's also been known to set up shop in the latest MMO and likes to wind down with an endlessly deep, systemic RPG. These days, when he's not editing, he can usually be found writing features that are 1,000 words too long or talking about his dog.