How Hero-U avoided disaster to resurrect '90s adventure game nostalgia

Despite a lengthy, somewhat troubled development cycle, Hero-U is a worthy successor to Sierra's Quest for Glory.

Lori and Corey Cole are the husband-wife team responsible for over a dozen of Sierra Entertainment adventure/role-playing games. Most notably, the two are the creators of Quest for Glory but are also known for their work on early King's Quest games. Hero-U: Rogue to Redemption is their first game they've made together in almost 20 years.

Six years, two Kickstarter campaigns, and one home equity loan later, Hero-U: Rogue to Redemption was finally released. “A year after the first Kickstarter we were approached by an outside investor,” says Corey Cole, part of the husband-wife team behind Hero-U. “We would’ve gotten half a million in additional funding. The problem was they wanted 50% of the game’s sales for life. At the time we felt it was too much to give up. Had we looked into our crystal ball in 2015 or 2017, we would’ve jumped on that.”

I spoke to both Corey and Lori Cole about the lengthy, yet passionate development of Hero-U, an adventure-RPG modeled after the 1990s Sierra series that once made them design icons: Quest for Glory. After being Kickstarted the same year as Double Fine's Broken Age, Hero-U finally, and quietly, released on Steam on July 10, 2018. If you hadn't been following its development, you probably missed it.

And even if you scrolled past Hero-U on Steam, you'd likely have no idea it came from the creators of one of Sierra's most beloved adventure series.

The first Quest for Glory, released in 1989, was also the first game the Coles worked on together at Sierra. “We met at a science fiction convention at San Francisco,” says Lori Cole. “Corey was running a game of Dungeons & Dragons and invited me to play the game.”

Adds Corey: “We needed another player, but I also thought she was cute!”

The Coles worked on several adventure-style games at Sierra throughout the 1990s, filling the roles of programmers, co-designers, writers, and directors. Corey also directed the educational Castle of Dr. Brain. But it was their Quest for Glory games that remain fan favorites.

So You Want to Be a Hero

The Quest for Glory series, which eventually encompassed five games across nearly a decade, are a unique hybrid of classic 2D point-and-click adventure like King’s Quest, infused with RPG features like raising stats, solving quests, and combat. Players select a fighter, rogue, magic-user, or later, a paladin to determine which skills and abilities they will use to fight monsters and tackle puzzles.

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

We used an adventure game engine for Quest for Glory because that’s what Sierra had, and where their strengths were. But we always considered ourselves role-playing game designers.

Corey Cole

“We’re known as adventure game designers but we really don’t play many adventure games,” says Corey. “We used an adventure game engine for Quest for Glory because that’s what Sierra had, and where their strengths were. But we always considered ourselves role-playing game designers.”

The Quest for Glory games were beloved for their lovely 2D artwork, memorable characters, and humorous writing, though the Coles are quick to point out that nostalgia has helped highlight the series’ strengths and minimize its flaws, particularly the bugs. “When we shipped Quest for Glory 4 on floppy disks, it was pretty much unplayable,” says Corey.

Thankfully Sierra later released a much better CD-ROM version of Quest for Glory: Shadows of Darkness that included numerous bug fixes as well as full voice acting. That CD version was one of the first PC games I ever played, and remains one of my favorite games to this day, leading me to quickly back the Hero-U: Rogue to Redemption Kickstarter in the fall of 2012, along with about 6,000 other nostalgic fans.

“Tim Schafer and the Double Fine Adventure was so successful, we ended up getting dozens of emails and phone calls—someone actually tracked down our phone number,” says Corey. “Fans told us to check out this Kickstarter thing and kickstart a new Quest for Glory.”

The Coles had been relatively quiet after their careers at Sierra, having initially entered the gaming industry well into their 30s back in the late 80s. In the 2000s, Lori turned a fan request to do a collaborative Quest for Glory novel into an interactive website, which then evolved into an ARG-like role-playing experience.

“The idea was for a fantasy version of a school, called The School for Heroes,” says Lori. The Coles had been expanding upon the hero school concept, and upon seeing the success of Double Fine Adventure, adapted it for their Kickstarter project. But that wasn't the game they'd end up making.

Back to School

“We naively thought we could go up on Kickstarter and make a really great RPG,” says Corey. “It would be modeled like Rogue, but with lots of story and characters. But people couldn’t imagine it. The roguelike genre has become a pure concept that’s gone in a completely different direction, including things like permadeath that we don’t believe in. A week into the Kickstarter we got comments from people who wanted to support us because we were ‘The Coles,’ but the actual game we were presenting wasn’t really what people wanted. They wanted another story-driven game like Quest for Glory.”

Wanting another Quest for Glory game from the beloved designers of a beloved series doesn’t seem surprising, but it came as a shock to both of them. “We underestimated the power of fandom!” says Lori.

The development proved challenging right from the beginning, as the Coles struggled to adjust fan expectations with their own vision of Hero-U. “We developed our initial look of the game based on the MacGuffin’s Curse engine,” says Corey.

We naively thought we could go up on Kickstarter and make a really great RPG.

Corey Cole

Adds Lori: “We really wanted to do a small-scale, easy to do game that had elements of Quest for Glory—but not a full-scale adventure role-playing game.” Fans quickly balked at the style. It looked nothing like the classic Sierra adventures.

A month after the Kickstarter campaign ended, Andrew Goulding, the developer of MacGuffin's Curse, told the Coles he couldn't work on the project. This was a significant blow, as Goulding had initially talked the Coles into doing the Kickstarter project using his developers and his code base.

“He had a crisis of conscience,” says Corey. “It was partly miscommunication, and partly realizing he had spent 60-70 hours of his own free time to make [his games] affordably. With our blessing he dropped off the project so he could pursue higher paying contracts. He offered to allow us to use his engine but we didn’t want to do that without the creator.”

Terry Robinson, whom the Coles had worked with on Quest for Glory 5, offered to join the team as art director. Robinson provided further motivation to change the entire graphical style of Hero-U. “He came in and looked at MacGuffin’s Curse and said, ‘I’m not doing a game like this, it doesn’t look good.’ He came up with the isometric view and developed the look and feel of the game.”

The Coles then ran into problems trying to do 2D animation within Unity. “We couldn’t find any good programs to animate characters as good as the old Sierra style from 20 years ago,” says Lori. “And we couldn’t find anyone who specialized in 2D animation anymore. We wanted to put out a quality product, and that meant going 3D. By the time we did the second Kickstarter campaign, we were fully committed to producing a 3D game, which meant recreating art and hiring 3D artists.”

With both sudden and gradual shifts to Hero-U’s core design and visual styles, much of the work through 2013 and parts of 2014 were spent prototyping, none of which would be used for the final game. “In 2014 we spent a substantial amount of our bankroll getting 3D character designs and models,” says Corey. “I’d stretched one year of Kickstarter money into two years of development, and we still had at least a year to go. That’s when we did the second Kickstarter.”

When asked about the second Kickstarter campaign, which ran in 2015, Corey is quick to point out the equally troubled development of Double Fine’s Broken Age, which had to eventually be broken up into two different episodes with sales of the first helping fund the second half.

Corey also admits to some budgetary mistakes. “We asked for $400,000 because that’s what Double Fine had asked for. It’s also about what our first two games, Hero’s Quest and Quest for Glory 2, had cost,” he says. “But I didn't count for inflation. Those games probably cost a million or more to make today. And honestly, we asked for $400,000 and were hoping we would get $800,000.”

The first Kickstarter campaign barely reached the $400,000 funding goal. “Double Fine Adventure got 87,000 backers. We struggled to get 6,000. That’s still a lot of backers but not what we expected. It’s real money from real players who weren't sure they’d ever see a game. They made it possible, but it wasn’t enough to make the game, unfortunately.”

By 2015 money had grown tight. The Coles were foregoing any personal salaries in order to pay programmers, artists, and musicians, some of who were taking reduced or deferred paychecks. “We couldn’t pay much but we had to make sure the paychecks were flowing,” says Lori. “As development dragged on it was clear that the money was going to have to come from us rather than just Kickstarter. We hoped it wouldn’t be too much money before we ran out.”

The second Kickstarter asked for $100,000 and sparked some justifiable outrage from fans. In a detailed Kickstarter post dated May 6, 2015 (the day after they announced the second Kickstarter campaign), the Coles broke down the exact costs of the project up until that point, including tens of thousands of dollars of early work that would never be used. At that point the Coles revealed they had taken out a $150,000 home equity loan to pay their own living expenses while Hero-U was in development.

Our personal resources weren’t great but we owned a house, and had some retirement money we could draw on. It’s a tremendous risk, and still is.

Corey Cole

“We didn’t have deep pockets or upfront investors,” says Corey. “Our personal resources weren’t great but we owned a house, and had some retirement money we could draw on. It’s a tremendous risk, and still is.”

With the help of some actual gameplay demos the second campaign proved successful in raising another $100,000 for the project, though now at release Corey estimates the total cost of Hero-U is closer to a million dollars.

To Catch a Thief

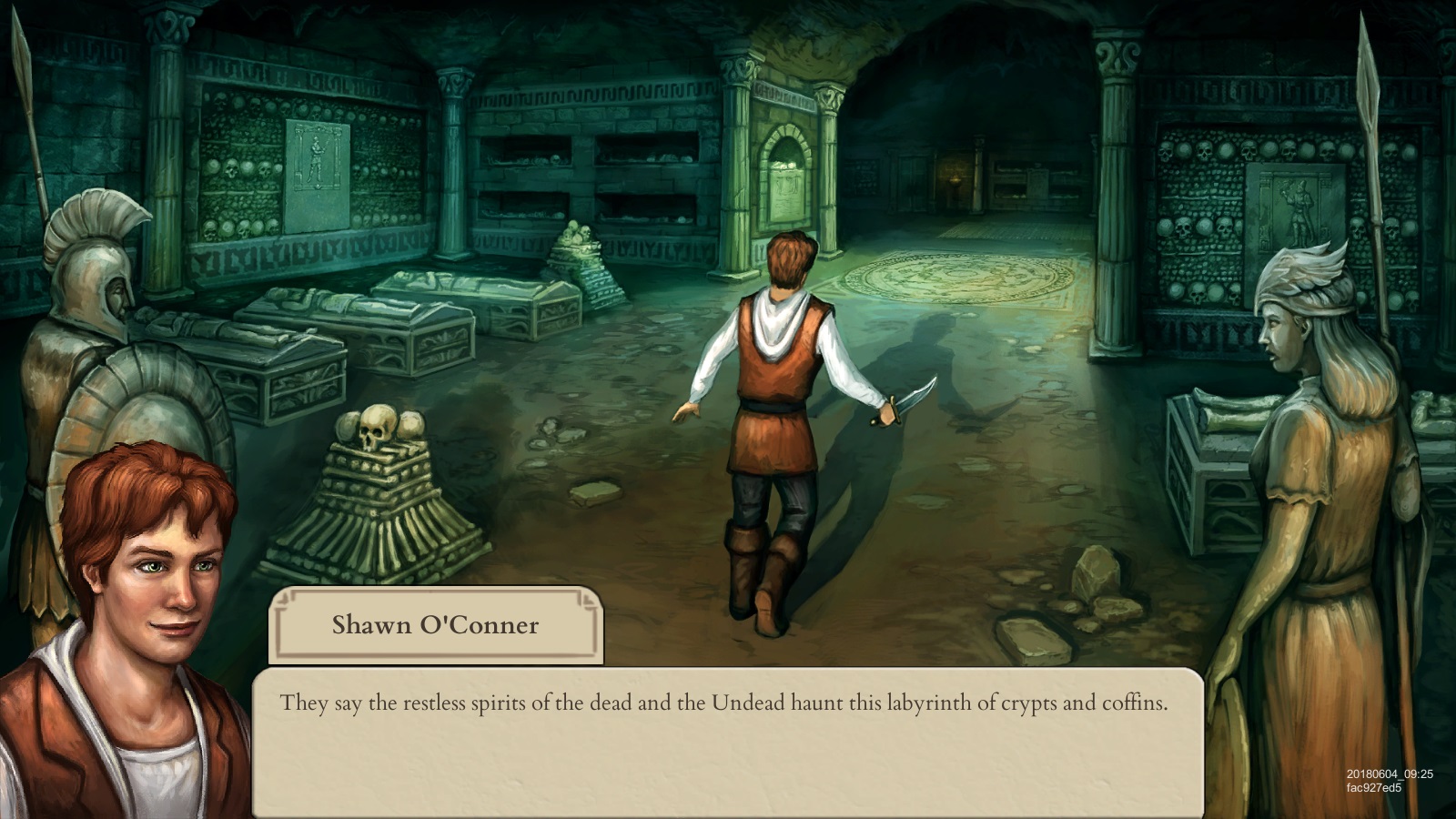

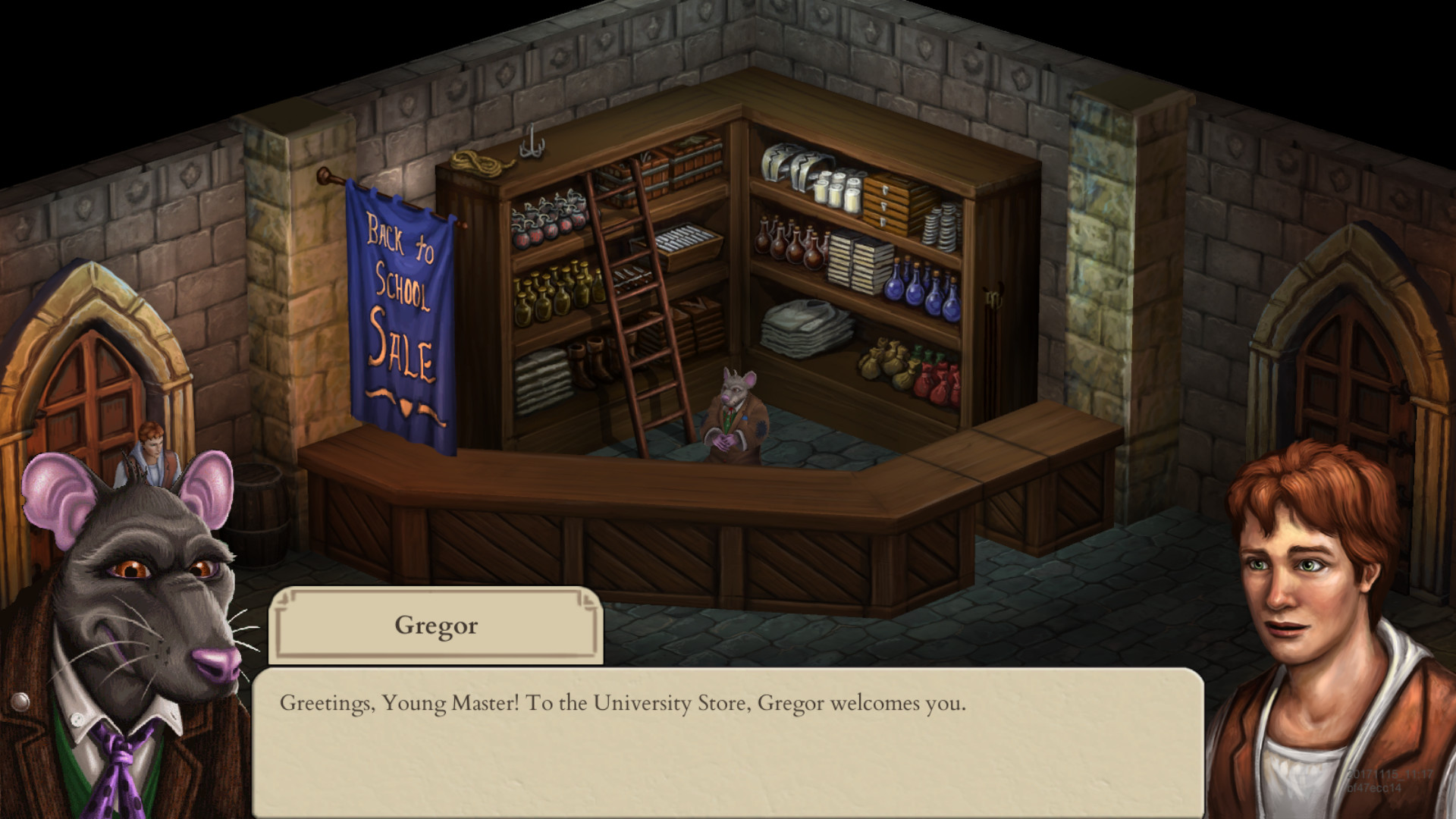

Playing Hero-U as a Quest for Glory fan hits all the right nostalgic buttons. The 2D artwork is frequently gorgeous, including the many backer-inspired paintings that adorn the hallways. The dialogue is punchy and entertaining like a good novel, and every student and faculty member at the university has their own unique personality and goals.

For Quest for Glory fans, it’s like if you had a bigger, more interactive hub town, but you never actually left it, which is admittedly jarring at first. All the adventuring is done within the magical university, and if you’re making Harry Potter comparisons in your head, you’re not the only one.

“Our setting is definitely fantasy-humor,” says Corey. “It’s like reading a Harry Potter book, with a lot more humor thrown in. Our original planning was to do the wizard game first, but we didn’t want people to think that we were ripping off Harry Potter. In hindsight the Harry Potter comparisons are probably not a bad thing.”

The focus on time management makes Hero-U almost play more like Persona or Stardew Valley. I had forgotten that the QFG series always featured a progressive day/night cycle, including scripted events that were tied to certain days. “Quest for Glory 2 in particular was very time- and event-driven,” says Lori. “Players have less agency, but it also means you have to really work, and creates dramatic tension. In Hero-U you’re not the only hero who can save the day. There’s no fail state, but events will change and people can die because you didn’t do something.”

Having different outcomes and multiple endings rather than game over screens (or worse, simply getting stuck) is one of the many welcome modern improvements in Hero-U. The turn-based combat is also a notable improvement over QFG’s arcade-like click-fest, though hunting rats in the cellar is a fantasy trope I could definitely live without ever seeing again.

Hero-U’s biggest change over QFG is that it’s a much longer game. The Coles estimate that at around 25 hours it’s about four times as large as any QFG game, and it’s impossible to see everything in a single playthrough. Hero-U is definitely not the small-scale game they originally envisioned creating. “You’ll need to play through at least three times to see everything in the game,” says Corey. “We’ve had players put 100 hours into it.”

The Hero-U Cinematic Universe

The Coles wanted Hero-U to be a great game, but they also wanted it to be the start of a whole new series. Like Harry Potter, each Hero-U story would be set at the university, but would feature a different hero character.

We have to at least break even on Hero-U. It was a very expensive game, but we’re optimistic.

Lori Cole

The second game, tentatively titled Hero-U: Wizard’s Way, would star a female wizard character, the third a warrior, the fourth a paladin. The fifth game would feature an Avengers-like crossover where all the heroes come together to fight an ultimate evil, allowing players to select different heroes to play during different points in the game—a nod to the nifty feature of importing characters into each Quest for Glory game.

Those future games depend on how well Hero-U: Rogue to Redemption sells. A launch price of $35 puts Hero-U in the upper-echelon of indie games, and the Coles are quick to point out the costs versus the original Quest for Glory games. “Hero-U is bigger than anything we did at Sierra. We spent five and a half years on it,” says Corey. “We looked at a $40 price point but GOG balked, and said we couldn’t charge that much for an indie game. We’re getting some complaints about the price, but taking in inflation, the first Quest for Glory game was about $100 at launch.

“We have a million dollars to recoup, and we’re not going to sell hundreds of thousands of copies. A lot of indie games that come out for $10 really sell themselves short,” says Corey. “We’re not looking to get rich from these games, but we’re looking at getting a sustainable income that allows us to pay people and keep making games. You can wait two years for the price to drop but by then the developer will be gone and that’ll be the last of the series.”

The Coles plan on returning to crowdsourcing for future games, mainly as a way to involve the community and gauge fan reactions. A six year development cycle isn’t sustainable, but they assure me they have it down to about three years per game. “With Hero-U we had about two years of experimentation,” says Corey. “Then two and a half years of development, and a year of testing.”

“We have to at least break even on Hero-U,” says Lori. “It was a very expensive game, but we’re optimistic. We’re working on the sequel now, developing the characters and art.”

“The nice thing about doing a crowdfunding campaign for Hero-U: Wizard’s Way is that we already have Rogue to Redemption to show off,” Corey adds.

Many crowdfunded projects over the last half decade have proven that just because an original designer wants another chance at a greatest hit, it doesn’t necessarily equate to success, or even a good game. But Quest for Glory fans can be assured that Hero-U: Rogue to Redemption is a bulky, yet worthy spiritual successor, and the Coles are nothing if not extremely passionate about creating another beloved series of adventure-role-playing games.

The real challenge will be enticing those who lack the nostalgia of 90s era Sierra games to see what all the fuss is about. “It’s a niche game but people who love story and love humor are going to love this game,” says Corey.

“We’re very proud of this game," Lori says. "We think it really reflects the intensive game experience that you’ll never forget once you play it.”