How Hellblade's permadeath works isn't the point

Why the foreboding permadeath warning is great game design and a modern expression of unreliable narration.

Spoiler warning! Big plot points and systems are talked about at length, so be sure to finish Hellblade before reading.

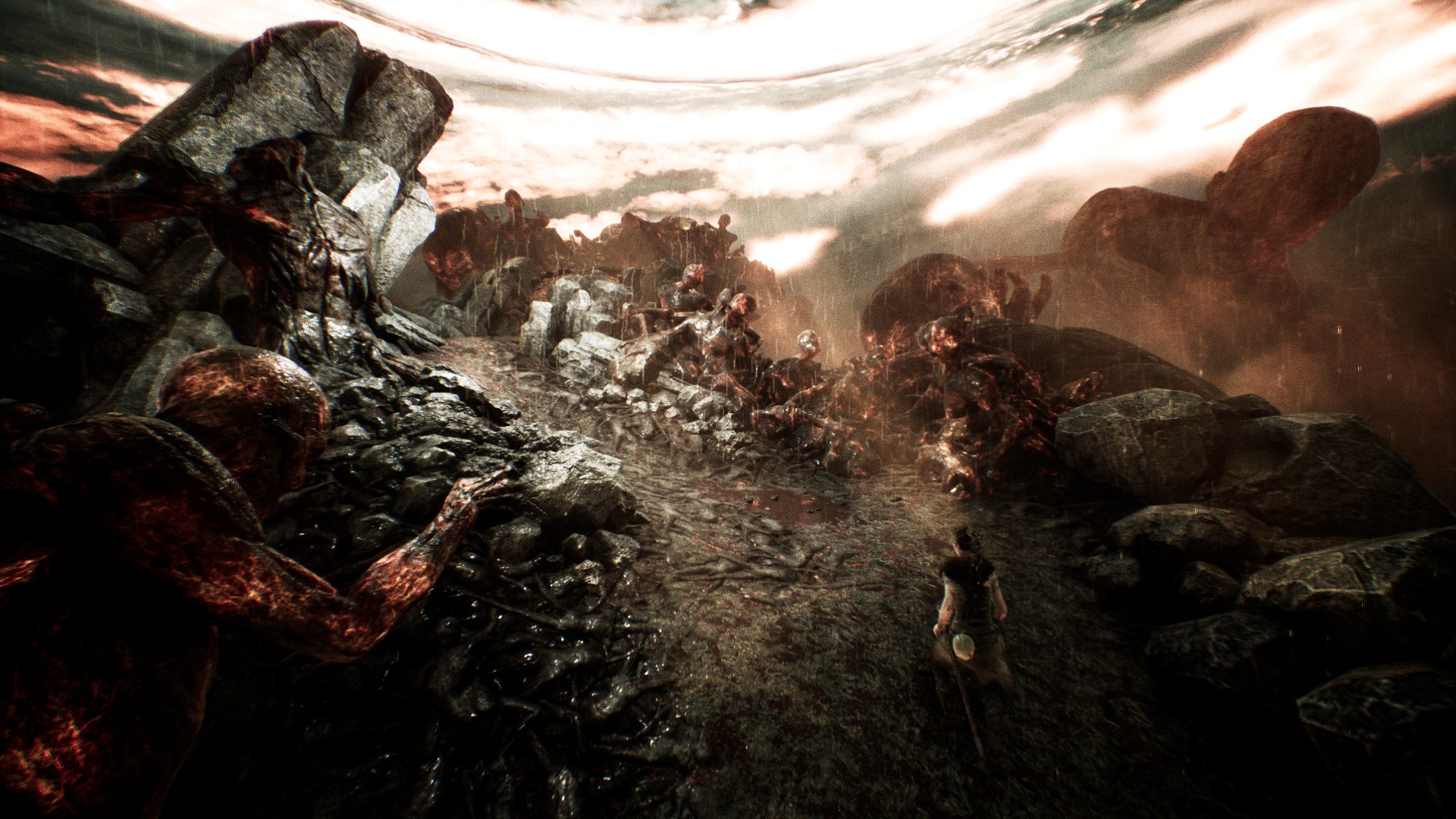

Hellblade: Senua’s Sacrifice makes no compromise. A rarity in games, and now the subject of depressing internet controversy because of it, every aspect of its design works to impart its message. It tells the story of a young, mentally ill Pictish warrior on a journey to the heart of Norse hell, throughout which she faces an overwhelming, horrifying darkness, both literal and metaphorical. Senua fights demons with a sword, but she’s also forced to grapple with internalized torment so profound that each step toward the story’s conclusion feels like an act of unimaginable pain. Making you feel warm and fuzzy and strong isn't a priority.

It’s a game of uncommon thematic consistency, willing to test the resolve of its audience so that they struggle in tandem with the character they control. Though there are many examples of the ways it does that, from impeccable audiovisual work to actor Melina Juergens’ heartrending performance, critics and players have centered conversation about the game on one specific point: Hellblade’s use of a supposed “permadeath” system that resets all progress if Senua is killed too often.

It makes sense that players, without knowing how the entire game plays out, would be concerned that the hours they’ve spent solving puzzles and killing demons could be erased after one slip-up too many. But that looming sense of dread—the fear that so much time and energy guiding Senua through hell could be futile—is a crucial part of what makes Hellblade’s narrative so successful.

Hela no, we won't go

Early on, marked by a first encounter with Hela, ruler of the underworld, Senua’s right hand turns black to signify her infection by an evil, corrupting force. Every time she’s struck down, the infection travels further up her arm, thick black veins spreading necrotized tissue toward her head. Die too often, the game says in plain text, and “all progress will be lost.” It’s a twist meant to instill big, definite stakes—if Senua can’t triumph over evil, neither can the player. Put in game jargon, it’s a “permadeath” system that ups the stakes of defeat by doing away with the endless chances usually granted by modern games, particularly those whose priority is to tell a story.

Permadeath is an attempt to bridge the divide between reality and fantasy, to truly kill a character dead rather than allow them to exist as an endlessly reborn demigod. It's rare because losing progress can be frustrating, especially progress through a narrative-heavy game that will play out roughly the same way a second time. Imagine having to stop a movie 90 minutes in, then rewatch the whole thing just to see the ending.

But Hellblade isn't a movie, and in a game, permadeath can be an effective narrative tool. Each time Senua's corruption progresses—ropey veins and charred-looking flesh consuming her arm—it marks a real danger to her ability to keep fighting toward her goal. That threat to her, and the player, represents evil, defeat, and hopelessness.

The biggest gaming news, reviews and hardware deals

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

Part of the corruption's success as a design choice is in how unpredictable it is, spreading or staying the same depending on accumulated deaths, important plot points, and other variables that, thankfully, haven’t yet forced into the public eye by eager data miners. As the story progresses, the nature of the corruption becomes clearer as the player comes to understand a correlation between Senua’s backstory and psychology and the way they perceive the game’s dangers. It is a beautifully executed bit of narrative design, game systems and story working in tandem. Saying too much would be a major spoiler.

Yet a vocal segment of the internet has bristled at the idea of permadeath in Hellblade. The reasons why are sometimes baffling and manifold, running the gamut from that old blank slate accusation of bad game design to John “Totalbiscuit” Bain tweeting that the decision is bad for consumers. Arguments about what narrative games 'should' be have crowded out analysis and criticism of what Hellblade actually is.

The issue gets even more confused following reports that the entire permadeath system is a feint and that having to restart all the way back at the game’s beginning is either an impossibility or so difficult to trigger it may as well be.

Dying for a good cause

Lost in all of this is the purpose of Hellblade’s permadeath as a design choice. Whether it exists and how it happens has little to do with the fact that the game wants the player to feel like the stakes are high. Once Hellblade says that failing too often will erase all progress toward its end, each in-world danger gains weight. Like Senua, the player understands that what they’re trying to accomplish is enormously difficult. If she can’t press on, her very being will be obliterated. More than just her body, her soul will be consumed by the chaos of an indifferently malevolent hell. Allowing the player to feel even a fraction of that—for them to know that the data situating them in the game world could be thrown away—is a crucial component of her characterization.

Hellblade’s setting, a magical realist Scandinavian island where the line between myth and reality overlap completely, is overlaid with constant menace. Solving the game’s puzzles involves frustrated wandering back and forth through stinking swamps and the charred remnants of ruined Viking villages. In one sequence toward the end of the game, as Senua nears the confrontation with Hela the entire game has lead to, she stumbles into a maze where taking too long to find a way out results in her being consumed by waves of flame.

I wondered, just like the character I controlled, if everything up to that point had been futile—if I, not just Senua, had what it took to achieve her goal.

Soon after, she fights for her life against an enormous, boar-like demon that can kill her with one powerful attack. Fights can go wrong in an instant, and as the game wears on, the blue paint covering Senua’s brow cracks and rubs away. She picks up cuts. Her face becomes covered in the dirt, blood, and ash of hell as evidence of how much she’s been through to get as far as she has. But she, and the player, persist.

Moments like the boar encounter might be exciting in another game, but knowing that the entire story can end so close to reaching Senua's goal, they become terrifying—as close to life-and-death stakes as a game can manage. It’s a far cry from being beaten down, exhausted and at your mental and physical breaking point in the depths of hell, but the darkness that plagues Senua feels more and more authentic as the game goes on.

While trying not to lose my concentration in what seems an endless battle against waves of demons, I know that the wrong dodge or an opportunity to attack not taken won’t kill me, but each mistake could mean that a story I’m invested in will end. A sense of real dread creeps up in proportion to the progress of Senua’s rotting arm. Approaching the end of the game, afraid I’d made too many mistakes, I wondered, just like the character I controlled, if everything up to that point had been futile—if I, not just Senua, had what it took to achieve her goal.

Through coming to terms with how fragile their experience with the game might be, players just might come to understand a fraction of Senua’s mental illness, or at least empathize with her. Without the threat that everything could end for Senua and the player, I'm not sure Hellblade's tension and themes would have half the sticking power they do. It’s a bold design choice that willingly alienates anyone who won’t consent to try, despite the odds.

Whether the permadeath system does or doesn’t exist, how it works, whether it involves the kind of lying all storytellers are guilty of whenever they tell stories shouldn’t matter. In every other medium, from film and books, to music and visual art, audiences understand that each aspect of a work exists in service of its message. And all media we watch, listen to, or read gambles with our time.

The too-long rest before a song continues and the unreliable narrators of so much fiction are formal tools meant to lead listeners, readers, and viewers toward a specific feeling. Game design is no exception. The best should be able to play with our expectations—to use whatever means available to say what they want to say. Hellblade’s permadeath, no matter how it works, should be celebrated for this, not pushed back against without considering its purpose.