I know, I know, one man's dystopia is another man's utopia, and it's certainly easier to have a negative take on something than a positive one. But I struggle to accept that anyone could not feel a sense of disquiet upon hearing that you can now rent a human "brain organoid" for "realtime neural stimulation and reading".

No, this isn't the dream futurism of some techno-optimist, these in vitro "organoids" are actually available to rent right now from FinalSpark's Neuroplatform (via Tom's Hardware), FinalSpark being a wetware computing company.

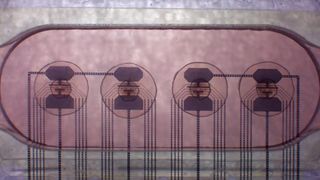

For just $500 per month (or free for some projects), university and education groups can access neuronic organoid bioprocessors, which are essentially collections of brain tissue, each containing thousands of living neurons, connected to electrodes on a chip.

The idea is to use biological matter for computational processing because it's far more energy efficient than using transistors. A research paper by FinalSpark explains that "we developed a hardware and software system that allows for electrophysiological experiments on an unmatched scale," allowing "researchers to run experiments on neural organoids with a lifetime of even more than 100 days."

Research can be conducted on these organoids remotely by using a Python Application Programming Interface (API) that FinalSpark developed. Based on my quick layman reading of the research paper, the experiments at this stage seem to involve discovering exactly how biological neural networks (BNNs) might work (eg, how stimulation and output works) and how they could be best used in future.

In other words, research at this stage seems to be laying the groundwork for a much more efficient kind of neural networking than transistor-based (artificial) neural networking. This being, y'know, living neural networking, which I might hesitantly call a kind of brain control.

Perhaps I'm too much of a sentimental, head-in-the-clouds philosopher (though I'd dispute that commonly espoused philosophy-clouds link) but, while Neuroplatform is certainly terrifyingly impressive, I can't help but focus on the "terrifying" part and reel at the thought of using what is essentially (part of) a brain in a vat for computation in this way.

The biggest gaming news, reviews and hardware deals

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

The "brain in a vat" scenario, popularised by philosopher Hilary Putnam, is a thought experiment that asks us to consider how we know we're not actually brains in vats, having our neurons stimulated in such a way as to generate the seeming reality around us, kind of like in The Matrix.

What is artificial general intelligence?: We dive into the lingo of AI and what the terms actually mean.

"Wetware" research like this, however, makes me wonder about an inverse thought experiment: How do we know the brains in vats we're stimulating aren't experiencing their own seeming reality in some limited form? How do we know they're not conscious to some limited extent?

And if we don't know that, what are the possible ethical implications of using such brain tissue for research? I've been reading Ray Kurzweil's The Singularity is Nearer, and he suggests that if there's a possibility that AI could be conscious, we have an ethical responsibility to treat it as such. Perhaps this wetware poses the same responsibility: If there's a possibility that it could be conscious, even to some very limited extent, then perhaps we should treat it as such.

Furthermore, what will be the psychological and societal effects of treating brain matter as a commodity for data-churning and computation? And where might progress in such wetware research lead in future? Do we really want to learn exactly how to control brains, and therefore possibly minds, computationally?

These are questions that I suppose can also be asked about brain-computer interfaces (BCIs). There's just something a little more in-your-face terrifying about brain tissue in vitro, attached to a chip, being stimulated and recorded over and over for its 100-day lifecycle. Progress marches on regardless, I guess.

Jacob got his hands on a gaming PC for the first time when he was about 12 years old. He swiftly realised the local PC repair store had ripped him off with his build and vowed never to let another soul build his rig again. With this vow, Jacob the hardware junkie was born. Since then, Jacob's led a double-life as part-hardware geek, part-philosophy nerd, first working as a Hardware Writer for PCGamesN in 2020, then working towards a PhD in Philosophy for a few years (result pending a patiently awaited viva exam) while freelancing on the side for sites such as TechRadar, Pocket-lint, and yours truly, PC Gamer. Eventually, he gave up the ruthless mercenary life to join the world's #1 PC Gaming site full-time. It's definitely not an ego thing, he assures us.

Nintendo has delayed Switch 2 pre-orders in the US 'to assess the potential impact of tariffs' and it feels like a straight warning of the hardware price rises to come

Keychron's M5 wireless ergonomic mouse has an 8K polling rate for 'ultimate control in gaming scenarios' making it a gaming mouse with a, err, twist