NASA manages to fix Voyager's garbled data problem, even though it's more than 15 billion miles away

With hardware older than an Atari 2600, it's amazing Voyager 1 is still even running, let alone sending gobbledegook.

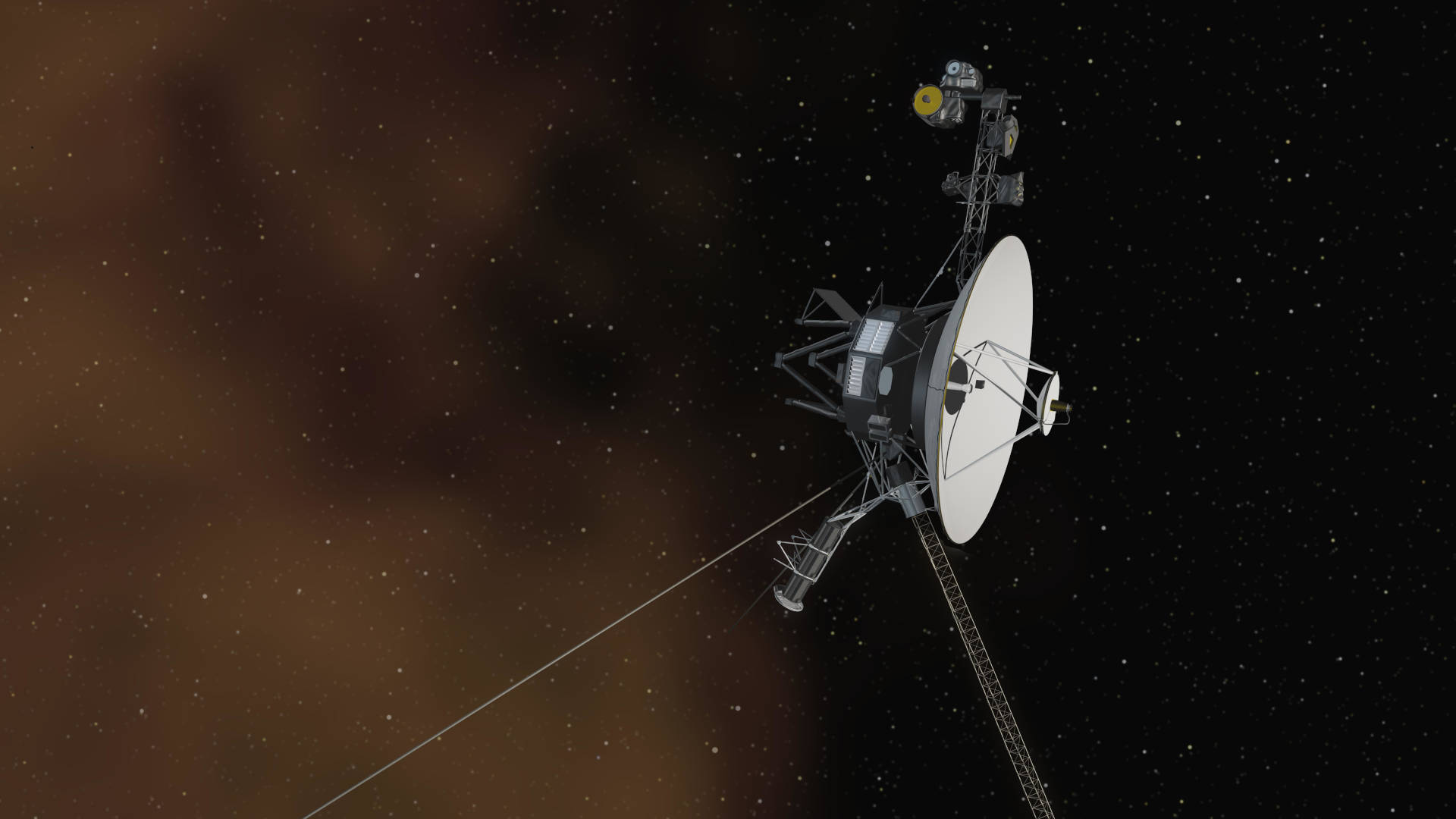

Back in November, NASA's second longest-running spacecraft Voyager I began sending data that made no sense whatsoever. Instead of information about its status and what various sensors were recording, all the scientists got was a meaningless repeated pattern. Well, after much head-scratching and hard work, engineers have fixed the issue and confirmed that Voyager I is transmitting properly once more, from the depths of interstellar space.

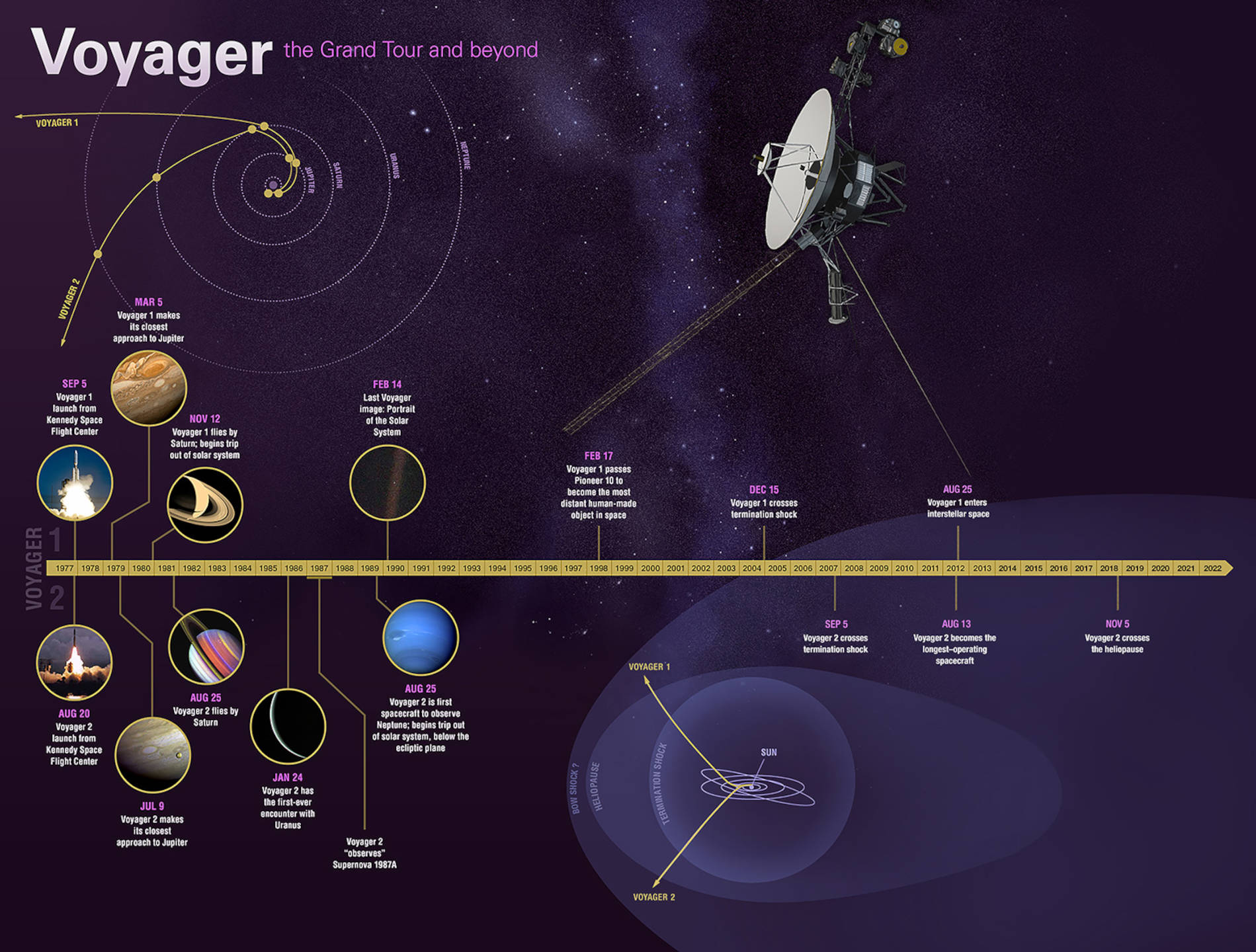

Launched in 1977, Voyager I was part of a twin spacecraft mission to study the gas planets, flying past Jupiter and then Saturn, before heading off out into the unknown. Powered by a radioisotope thermoelectric generator (RTG), it continued to send back data to Earth and in 2012, it crossed the heliopause and officially entered interstellar space.

It's fair to say that nobody really expected the spacecraft to continue functioning for so long but despite a few glitches along the way, it's continued to provide valuable information about the nature of our Solar System.

That was until November 2023, when its Telemetry Modulation Unit (TMU) appeared to have failed, as it just sent a constantly repeating pattern of data. NASA's engineers ultimately discovered that the TMU was working as intended—the issue was one of the ancient memory chips for the Flight Data Subsystem (FDS) had failed, either due to a high-energy particle wrecking it or just through over four decades of wear and tear.

Since that chip stored instructions for how the FDS should communicate with the TMU, its loss meant the latter had no way to work properly. The two Voyager spacecraft were some of the first ever to use volatile memory to store data, so it's remarkable that they've lasted as long as they have. But with the problem identified, a solution could be developed and it was about essentially figuring out which code had been lost and then resending it to be stored on another memory chip.

Not that it would be a quick fix. Voyager I is over 15 billion miles away and it takes around 22.5 hours for a radio signal to reach it and then another 22.5 hours for any response to return to Earth—imagine clicking on a desktop icon and waiting for nearly two days for it to activate, and you'll get a sense of how challenging it is to work with the spacecraft.

NASA can only send part of the required instructions in any one signal but the first batch was sent on April 18. Two days later, a response was received indicating that the memory relocation had gone as planned and the spacecraft could now correctly report its status.

The biggest gaming news, reviews and hardware deals

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

Over the next few weeks, the engineers will continue to move the code for the FDS into other memory locations and once complete, Voyager I will be able to send scientific data back.

Best DDR5 RAM: the latest and greatest

Best DDR4 RAM: affordable and fast

At some point in the next few years, the RTG will no longer have sufficient radioactivity to power the spacecraft's transmitter and it will fall silent for good. By 2036, even if it does somehow continue to work, Voyager I will be too far for NASA's Deep Space Network.

We'll probably never know the ultimate fate of the incredible machine but its discoveries have been an astonishing testament to the skill and ingenuity of NASA scientists and engineers.

Somehow I doubt anything in my current PC will last half as long but if it does start going wonky, I think I know who might be best at fixing it.

Nick, gaming, and computers all first met in 1981, with the love affair starting on a Sinclair ZX81 in kit form and a book on ZX Basic. He ended up becoming a physics and IT teacher, but by the late 1990s decided it was time to cut his teeth writing for a long defunct UK tech site. He went on to do the same at Madonion, helping to write the help files for 3DMark and PCMark. After a short stint working at Beyond3D.com, Nick joined Futuremark (MadOnion rebranded) full-time, as editor-in-chief for its gaming and hardware section, YouGamers. After the site shutdown, he became an engineering and computing lecturer for many years, but missed the writing bug. Cue four years at TechSpot.com and over 100 long articles on anything and everything. He freely admits to being far too obsessed with GPUs and open world grindy RPGs, but who isn't these days?