I've been testing Nvidia's new Neural Texture Compression toolkit and the impressive results could be good news for game install sizes

Big textures go tiny but there is a price to pay.

At CES 2025, Nvidia announced so many new things that it was somewhat hard to figure out just what was really worth paying attention to. While the likes of the RTX 5090 and its enormous price tag were grabbing all the headlines, one new piece of tech sat to one side with lots of promise but no game to showcase it. However, Nvidia has now released a beta software toolkit for its RTX Neural Texture Compression (RTXNTC) system, and after playing around with it for an hour or two, I'm far more impressed with this than any hulking GPU.

At the moment, all textures in games are compressed into a common format, to save on storage space and download requirements, and then decompressed when used in rendering. It can't have escaped your notice, though, that today's massive 3D games are…well…massive and 100 GB or more isn't unusual.

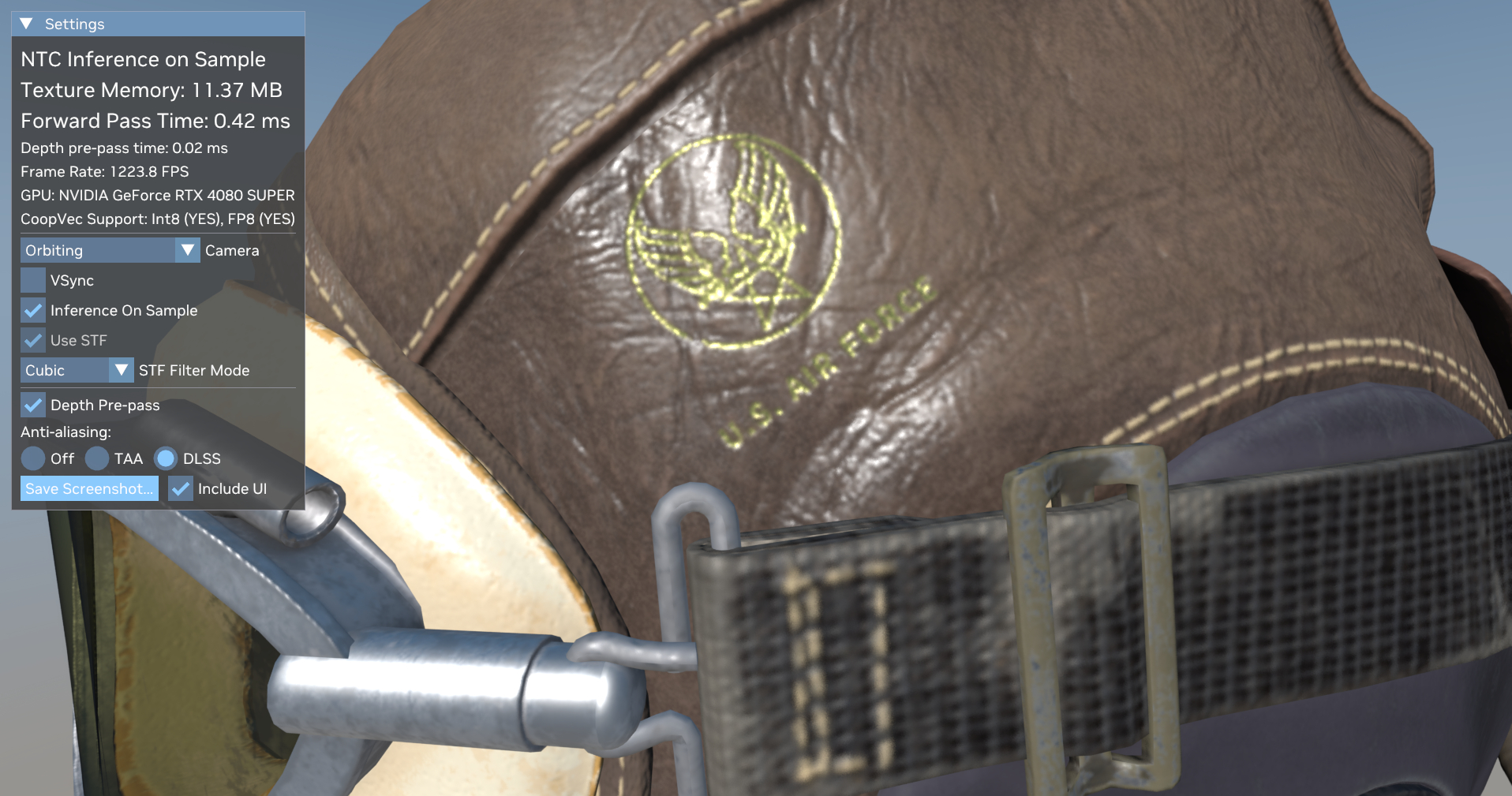

RTXNTC works like this: The original textures are pre-converted into an array of weights for a small neural network. When the game's engine issues instructions to the GPU to apply these textures to an object, the graphics processor samples them. Then, the aforementioned neural network (aka decoding) reconstructs what the texture looks like at the sample point.

The system can only produce a single unfiltered texel so for the sample demonstration, RTX Texture Filtering (also called stochastic texture filtering) is used to interpolate other texels.

Nvidia describes the whole thing using the term 'Inference on Sample,' and the results are impressive, to say the least. Without any form of compression, the texture memory footprint in the demo is 272 MB. With RTXNTC in full swing, that reduces to a mere 11.37 MB.

The whole process of sampling and decoding is pretty fast. It's not quite as fast as normal texture sampling and filtering, though. At 1080p, the non-NTC setup runs at 2,466 fps but this drops to 2,088 fps with Interfence on Sample. Stepping the resolution up to 4K the performance figures are 930 and 760 fps, respectively. In other words, RTXNTC incurs a frame rate penalty of 15% at 1080p and 18% at 4K—for a 96% reduction in texture memory.

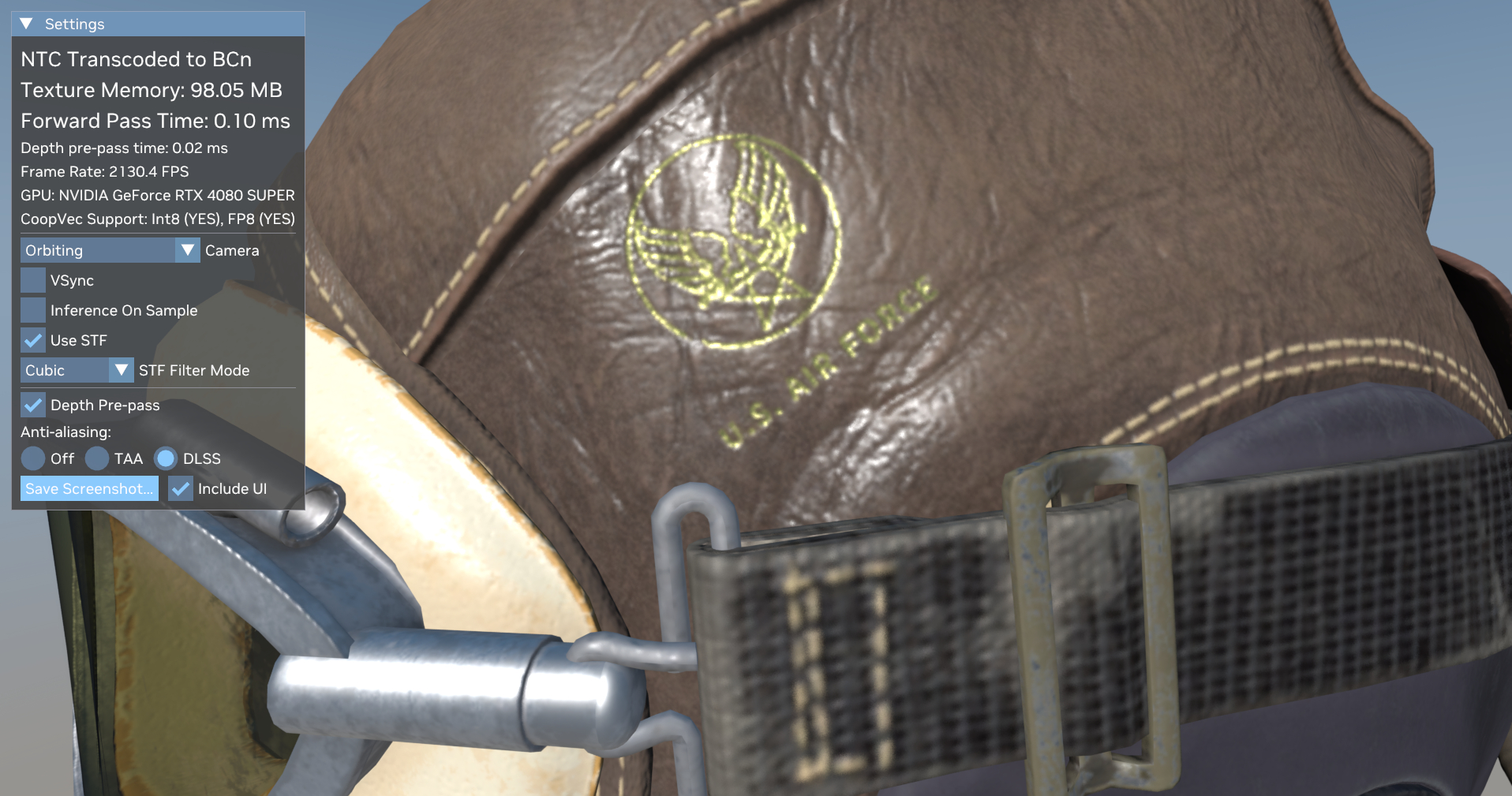

Those frame rates were achieved using an RTX 4080 Super, and lower-tier or older RTX graphics cards are likely to see a larger performance drop. For that kind of hardware, Nvidia suggests using 'Inference on load' (NTC Transcoded to BCn in the demo) where the pre-compressed NTC textures are decompressed as the game (or demo, in this case) is loaded. They are then transcoded in a standard BCn block compression format, to be sampled and filtered as normal.

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

The texture memory reduction isn't as impressive but the performance hit isn't anywhere near as big as with Interfence on Sample. At 1080p, 2,444 fps it's almost as fast as a standard texture sample and filtering, and the texture footprint is just 98 MB. That's a 64% reduction over the uncompressed format.

All of this would be for nothing if the texture reconstruction was rubbish but as you can see in the gallery below, RTXNTC generates texels that look almost identical to the originals. Even Inference on Load looks the same.

Of course, this is a demonstration and a simple beta one at that, and it's not even remotely like Alan Wake 2, in terms of texture resolution and environment complexity. RTXNTC isn't suitable for every texture, either, being designed to be applied to 'physically-based rendering (PBR) materials' rather than a single, basic texture.

And it also requires cooperative vector support to work as quickly as this and that's essentially limited to RTX 40 or 50 series graphics cards. A cynical PC enthusiast might be tempted to claim that Nvidia only developed this system to justify equipping its desktop GPUs with less VRAM than the competition, too.

Best CPU for gaming: The top chips from Intel and AMD.

Best gaming motherboard: The right boards.

Best graphics card: Your perfect pixel-pusher awaits.

Best SSD for gaming: Get into the game ahead of the rest.

But the tech itself clearly has lots of potential and it's possible that AMD and Intel are working on developing their own systems that achieve the same result. While three proprietary algorithms for reducing texture memory footprints aren't what anyone wants to see, if developers show enough interest in using them, then one of them (or an amalgamation of all three) might end up being a standard aspect of DirectX and Vulkan.

That would be the best outcome for everyone, so it's worth keeping an eye on AI-based texture compression because just like with Nvidia's other first-to-market technologies (e.g. ray tracing acceleration, AI upscaling), the industry eventually adapts them as being the norm. I don't think this means we'll see a 20 GB version of Baldur's Gate 3 any time soon but the future certainly looks a lot smaller.

If you want to try out the NTC demo on your own RTX graphics card, you can grab it directly from here. Extract the zip and then head to the bin/windows-x64 folder, then just click on the ntc-renderer file.

Nick, gaming, and computers all first met in 1981, with the love affair starting on a Sinclair ZX81 in kit form and a book on ZX Basic. He ended up becoming a physics and IT teacher, but by the late 1990s decided it was time to cut his teeth writing for a long defunct UK tech site. He went on to do the same at Madonion, helping to write the help files for 3DMark and PCMark. After a short stint working at Beyond3D.com, Nick joined Futuremark (MadOnion rebranded) full-time, as editor-in-chief for its gaming and hardware section, YouGamers. After the site shutdown, he became an engineering and computing lecturer for many years, but missed the writing bug. Cue four years at TechSpot.com and over 100 long articles on anything and everything. He freely admits to being far too obsessed with GPUs and open world grindy RPGs, but who isn't these days?