GPUs powering AI will probably be the end of us all but at least they're being used to find small city smashing asteroids before they do

Ten metres might not sound very big but just imagine dropping one on your toes.

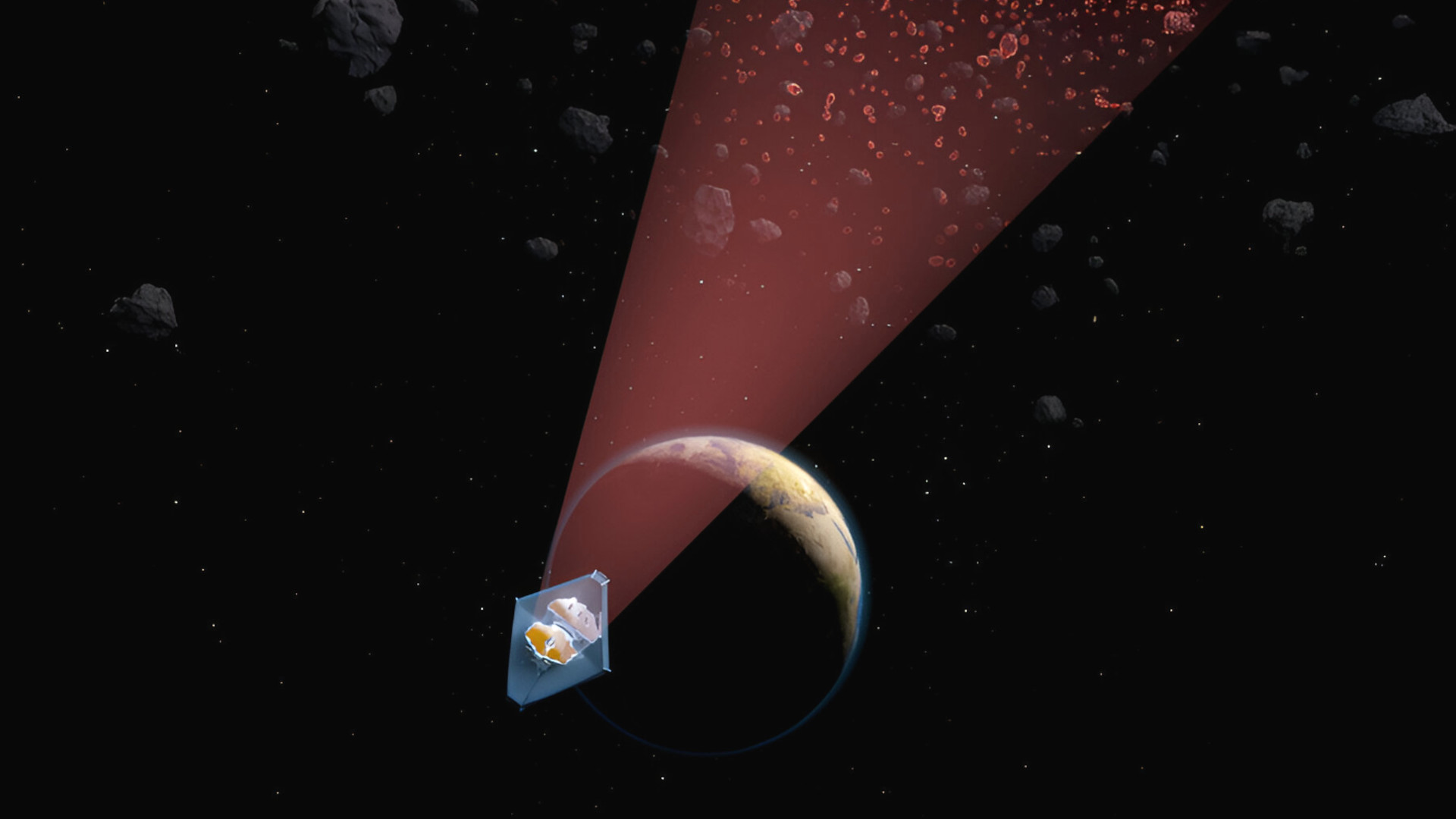

If you're a fan of 1990s disaster movies, you'll know all about the potential damage that an undetected asteroid could wreak if it impacted Earth. While finding massive metallic rocks in space is relatively easy, asteroids that are just ten metres in size are far harder to spot. A team of physicists at MIT, however, has worked with Nvidia to use its GPUs to make the process a lot better and faster, with 100 tiny doom-harbingers being successfully identified and tracked.

The good news was shared by Nvidia on its X account, and the details of the research were published in the February issue of Nature. The vast majority of asteroids orbit the Sun in a region of space called the Asteroid Belt, and they've remained there for billions of years. However, really small ones frequently get nudged out of the main belt and become NEOs—Near Earth Objects.

🌌 An international team of researchers, led by MIT physicists, are using the James Webb Space Telescope and NVIDIA GPUs to spot asteroids as small as 10 meters in the main asteroid belt, allowing the tracking of potential Earth-impacting asteroids.Read more about this research… pic.twitter.com/TSXY9Ts6BbFebruary 13, 2025

Such objects have the potential to cause significant damage if they ultimately impact Earth and over the years, there has been a more concerted effort to develop methods to scan space and find and track potential armageddon-bringers. That's relatively easy to do if they're big, but small ones—specifically 10 metres in size in the case of this research—reflect such little light that they just slip through the net.

Enter stage left, the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) and a global team of physicists led by researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Oh, and Nvidia. Using JWST's peerless ability to take super-sharp infrared images of objects in our Solar System, the team poured over hundreds of scans of the main asteroid belt, looking for the tiniest of moving dots.

Figuring out whether said dots were distant objects or something far closer to us involved the use of 'synthetic tracking techniques', and that's where Nvidia's GPUs come into play. In a similar way to how GPUs can be used to predict the colours of pixels in a game's frame, the team used the GPU to speed up the process of predicting the tiny dots orbits. Coupled with other data collated in the research, the method identified eight already-known asteroids and a further 138 unknown lumps of metallic rock.

"Today’s GPU technology was key to unlocking the scientific achievement of detecting the small-asteroid population of the main belt, but there is more to it in the form of planetary-defense efforts," said Julien de Wit, one of MIT's researchers. "Since our study, the potential Earth-impactor 2024YR4 has been detected, and we now know that JWST can observe such an asteroid all the way out to the main belt as they move away from Earth before coming back."

Other than this being great news for improving the defence of our planet against rogue asteroid impacts, it got me wondering whether GPU-powered movement prediction could ever become a thing in games.

The biggest gaming news, reviews and hardware deals

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

Best CPU for gaming: The top chips from Intel and AMD.

Best gaming motherboard: The right boards.

Best graphics card: Your perfect pixel-pusher awaits.

Best SSD for gaming: Get into the game ahead of the rest.

For example, anyone who's used DLSS frame generation will know that it adds some input lag to a game because the frames it creates have not been issued by the host computer—i.e. No input changes have been used to adjust the graphics.

However, if it's possible to predict how a player may move about in-game, based on a track of the history of the player's movements, then there's scope for an algorithm to be run just before the frame generation step.

Nvidia already makes a big deal out of the fact that its full DLSS 4 package is able to create 15 pixels on the basis of just one being rendered directly, so it seems to me to be a logical step to generate motion itself.

But while we're all complaining about fake frames and fake movement, at least we'll all be a little bit safer from experiencing the side effects of having a big lump of rock, whizzing through space, and then politely nosediving into our home planet.

Nick, gaming, and computers all first met in 1981, with the love affair starting on a Sinclair ZX81 in kit form and a book on ZX Basic. He ended up becoming a physics and IT teacher, but by the late 1990s decided it was time to cut his teeth writing for a long defunct UK tech site. He went on to do the same at Madonion, helping to write the help files for 3DMark and PCMark. After a short stint working at Beyond3D.com, Nick joined Futuremark (MadOnion rebranded) full-time, as editor-in-chief for its gaming and hardware section, YouGamers. After the site shutdown, he became an engineering and computing lecturer for many years, but missed the writing bug. Cue four years at TechSpot.com and over 100 long articles on anything and everything. He freely admits to being far too obsessed with GPUs and open world grindy RPGs, but who isn't these days?