Ducky's 'world's first' analog keyboard offers Cherry inductive switches and wireless—but is it better than Hall effect?

Inductive switches are reportedly as good as Hall effect without the high power draw.

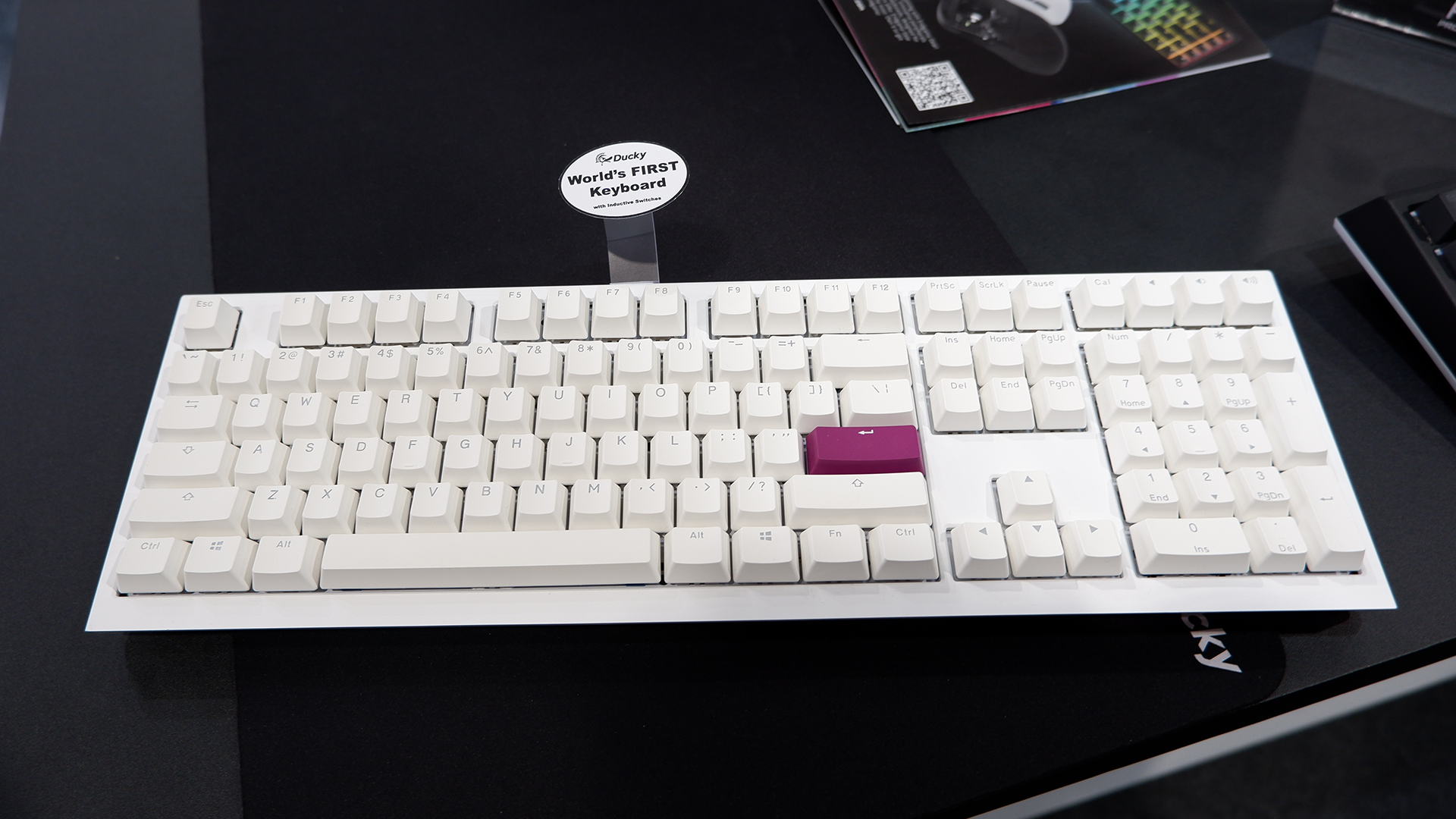

Inductive switches deliver analogue functionality without the high power draw of Hall effect. That's what Ducky claims at its Computex 2024 booth, anyways, where it's showing off the "world's first" inductive keyboard, the Ducky OneX.

It's built with Cherry's new Multipoint switches, though you'd be hard-pressed to tell at Ducky's booth. Cherry also wasn't making a massive song-and-dance about Multipoint at its own booth, though the switch is quite new.

The Ducky OneX will come in both full-size and 60% layouts. Personally, I prefer the full-size but I'm a sucker for a numpad. Both models offer tri-mode connectivity—2.4 GHz, Bluetooth, and wired via USB Type-C. The connection mode is switched on the rear of the keyboard.

"You don't see a wireless keyboard on those magnetic keyboards because they are power inefficient," Ducky representative Erik Hsieh tells me. "Our inductive analogue switches, they don't consume that much energy, so we are able to put to make them on a wireless keyboard."

The battery life reported on the two new Ducky inductive keyboards is reportedly "really great" too. Though it doesn't go into specifics.

Though I'm curious as to what actually happens with an inductive switch versus a Hall effect one, which measures a key press through a magnetic field. Kahwen Hsiao, Ducky's product management director, explains.

"There's a metal design inside the switch and you have all these coils on the PCBA that detects the movement," Hsiao says.

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

He also explains that while Hall effect requires a sensor for every switch, the inductive switches don't.

"Whatever number of keys you have, you have that number of [Hall effect] sensors to power. But for the inductive switches you have the coils that are already built into the PCBA. So that's why we can save a lot of power."

Though reportedly these switches can still offer the same feature set as magnetic switches, such as rapid trigger. This lets you hit a switch in quick succession for fast-paced gaming. It's also currently the feature most in-demand for analogue keyboards, according to Ducky and another analogue keyboard manufacturer, Wooting.

Hall effect versus inductive switches

I caught up with Wooting at its booth, who I prodded for information on Hall effect versus inductive. If anyone knows analogue switches, it's Wooting.

"So what we do is we have like a little magnet and a switch. Magnet moves out and you have the sensor at the bottom. But they don't have a magnet in the switch," Wooting's co-founder and CTO, Jeroen Langelaan says.

"They have a coil on the PCB. And then they have like a little piece of metal. The metal influences the coil and that's how you can kind of measure, okay, how far down they press the key."

And on how it stacks up to Hall effect: "I do think this [Hall effect] is better for now."

"Measuring inductance for a coil is quite difficult," Langelaan says.

Langelaan is keen to point out that in his discussions with Cherry, it does appear that its switch is about half the power of its own. Though also pointing out that, for gaming, Hall effect should be able to reach much higher polling rates, as they don't need to worry about drawing more power by scanning the keys more frequently.

The reason being an induction keyboard requires a few ICs to essentially run a cluster of switches.

"Because there's these ICs, and they need to measure all the calls, and it takes quite some time, they're limited in like how fast they can scan the keys."

But Wooting has switched to other key types in the past. It swapped from light-based switches to magnet-based ones. So, if it were to build a wireless keyboard, I ask if maybe something like this is on the cards.

To do wireless with this, you don't go Hall sensors, you go TMR sensors."

Catch up with Computex 2024: We're on the ground at Taiwan's biggest tech show to see what Nvidia, AMD, Intel, Asus, Gigabyte, MSI and more have to show.

TMR sensors are sorta similar to magnet switches, though they're a newer technology and power consumption is reportedly drastically reduced. Right now, it's still early days for these sensors, but watch this space.

"It's also kind of cool that like there's like more and more technologies about this coming up as well," says Langelaan.

"Like, I don't want to say like, 'oh, this [induction] is terrible', because it's not. It's just something different."

Simon Whyte, lead software engineer at Wooting, agrees. Though does point out that he disagrees with Cherry's claim to the "most precise switch."

I asked what the position was and they said 0.3 millimetre. And I'm like, 'Well, that is not the most precise'," Whyte says.

"I think maybe they were actually meaning the most accurate. Precision and accuracy are very distinct things."

The analogue keyboard competition has been heating up for a while now, but with Cherry in the game, we're likely to see induction keyboards from more than Ducky alone. For now, at least, the new Ducky OneX and Wooting 80HE look pretty great.

Jacob earned his first byline writing for his own tech blog, before graduating into breaking things professionally at PCGamesN. Now he's managing editor of the hardware team at PC Gamer, and you'll usually find him testing the latest components or building a gaming PC.