Gone Home, Thief, and the mansion genre

Robert Yang analyses Gone Home and its similarities to Thief and other inhabitants of the mansion genre.

This post does not spoil any specifics of the "plot" in Gone Home, but it might sensitize you to its delivery mechanisms and some details.

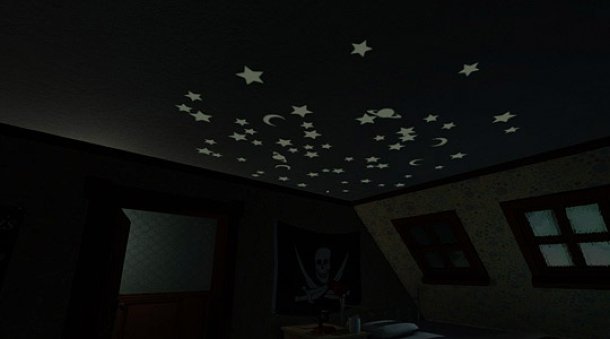

Mansions are old, rich, and scary. Most "mansion games" (like Maniac Mansion, Thief, or Resident Evil) emphasize these qualities for specific effect, and they would not work without the mansion tropes at the core of their designs. The video game mansion starts as an alien place that, through repeated visits and backtracking, becomes YOUR MANSION because you know all the rooms and secret passages and stories inside it.

Gone Home is very aware of its place in the mansion genre, a genre that emphasizes "stuff" and who owns it—inventories, objects, and possessions. Here, the lightweight puzzle gating and densely hot-spotted environments evoke adventure; the first person object handling and concrete readables evoke the immersive sim; the loneliness and the shadows evoke horror. In a sense, this is a video game that was made for gamers aware of all the genre convention going on (in particular, one moment in the library will either make you smile or wince, assuming you notice it) but in another sense, this is also a video game made for everyone.

A "gameism" (coined by Tom Bissell in his The Last of Us review) is a thing that makes perfect sense only within the context of a video game. Say you're playing an RPG and you talk to an NPC, and the NPC repeats the same line of dialogue over and over. Does that mean everyone in this town is a robot? No, it means the game is telling you to move on. So I shouldn't talk to any NPCs more than once? Well, not exactly. So when will an NPC say more than one thing? You'll just know.

This is extremely arbitrary and confusing for people who haven't played these games before. So Gone Home, among a growing number of narrative-based games, has a hunch: that a lot of these recurring gameisms stem from the huge gulf between an NPC's behavior and a semblance of consistency. Is it possible to have a game without NPCs, but keep the Cs? The answer is "yeah."

The characters in Gone Home are tolerable (or even great) because they do not hesitate in doorways and stare blankly at you. It's the same trick that Dear Esther pulled: fictional characters in games develop fuller-bodied, more nuanced personalities precisely when they're not constrained by fully simulated virtual bodies present in the world. (Maybe Dear Esther is actually a mansion game, in this sense?)

As invisible ghostly tour guides, these characters can narrate anything, anytime, without all the other problems that plague most virtual dramas: you don't have to justify how an NPC pathfound to your location, or why they react to some NPCs but not others, or what happens if you caress their face with with a box, etc. All these edge cases, these reactions that are complicated to engineer or script, easily created narrative dissonance for many players - but without NPCs, you no longer have to deal with them. So, I think the main strength of this narrative approach is that "plausibility of presence" becomes much less relevant.

The biggest gaming news, reviews and hardware deals

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

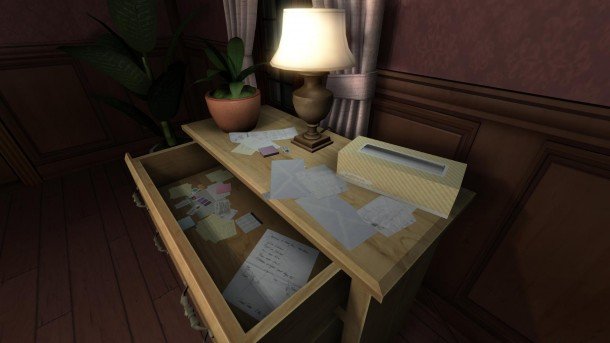

The word here is "interiority"—how we seem to have first-hand access to what the narrator thinks and feels. Everyone in this game pours out their feelings in numerous diaries and letters scattered around a house, which feels weird, but weird in the familiar way that novels are implausible, while also playing directly into the designers' hands. Does it feel weird and implausible only because we weren't white upper middle class American teenage girls living in the mid-1990s, bombarded by a particular strain of second-wave feminism that we can no longer identify with? Is this alienation similar to the alienation she was feeling?

A lot of Gone Home might feel alien to a lot of players, but unlike most sci-fi games, this game is actually about alienation from people and society. None of the characters feel particularly at-home in the mansion, and each family member is mostly buried in their own plot line and rarely interacts with the rest of the family. How can you connect with these people? Playing every first person shooter since Doom will not help you understand them any better because Gone Home leans on real-life cultural things, not game logic. Understanding what Reed College means, or what Riot Grrrl culture signifies, or who reads thriller paperback novels sold at airports, or what kind of person goes to Earth Wind and Fire concerts, or what a vapid postcard from a teenager in Europe sounds like... This game is less concerned with ludonarrative coherence than old fashioned narra-narrative coherence.

"Density" is Steve Gaynor's word for it. How much meaning are you packing into a space, and how does a player make sense of it? But filling spaces with stuff is useless if players don't know to look for it.

In Wolfenstein 3D, there were a few player strategies for finding secrets: unusual wall decoration, numerous wall alcoves, or certain wall sections framed peculiarly by plants or lights. There was also a second deeper strategy that you might call "layout analysis": to reason where hallways went and where space remained, to remember which areas you could see into but never actually visited. If you saw treasure or health behind a column, you knew there must have been a secret push-wall to get behind there, somewhere, somehow.

Thief framed "reading the environment" in a different way. Mansions offered probability puzzles, asking players to predict how much treasure will be in a given room (bathroom = 1% chance, bedroom = 40% chance, throne room = 100%, etc.) - and if you enter a king's bedroom, and there's no treasure to be found, then that makes no sense - and you'd better start looking for a secret button at his bedside, or a secret lever near the fireplace, or maybe douse the fire in the fireplace and look inside it.

It's about setting up patterns that players can read, and then pacing those patterns as informal puzzles. In this way, Gone Home functions much like Thief.

One bedroom might be densely packed with narrative objects and artifacts - which makes sense, because bedrooms are culturally read in Western culture as private spaces associated closely with specific person(s). However, you wouldn't expect a small half-bathroom to be nearly as personalized, especially if it connects directly to the foyer - that would be read as a public-facing bathroom for guests. The cultural program, imbued within your understanding of American mansion architecture, helps you play Gone Home and maybe even "solve" it.

Gone Home goes one step further though, and uses a sort of "layering" to forge connections between different objects. For instance, if you're in a public-facing room of the house, then who owns the stuff in that room? (A lot of Gone Home pivots on this question, of who owns which spaces?) To help you figure that out, objects frequently overlap each other: something that belongs to one character might sit on top of a leaflet they picked up, which sits on top of a letter they received. It uses these spatial connections to emphasize the narrative connections between things and what they symbolize.

It's also worth pointing out that Gone Home wouldn't feel nearly as fluent if it was made with technology from 10 years ago. Sufficiently advanced physics simulation that lets you stack stuff on top of stuff? Switchable dynamic lighting that help you remember whether you explored an area before or not? Very high resolution textures for all the different readables? I think we often pretend many video games could've been made at any time in the history of game development, and we downplay the influence of graphics technology as a mindless indulgence / crime against the Great God of Gameplay.

But I think a lot of Gone Home works because of where we are in video games today, design-wise and graphics-wise. It is totally a product of its time that strives to be timeless: it's like how you've never lived in a mansion, but you can totally sympathize with the people who do.

DISCLOSURE: Rob playtested Gone Home at various stages in its development. This article was originally posted on Rob's always-interesting Radiator Design blog.