Gone Home interview with Steve Gaynor: BioShock, the '90s, and what makes a "game"

The Fullbright Company is based out of a three-bedroom house in Portland, Oregon. Founders Steve Gaynor, Johnnemann Nordhagen, and Karla Zimonja don't just work in the house—they live in it. It's like the headquarters of an indie superteam: members of the group worked on BioShock 2, Minerva's Den, XCOM, and BioShock Infinite.

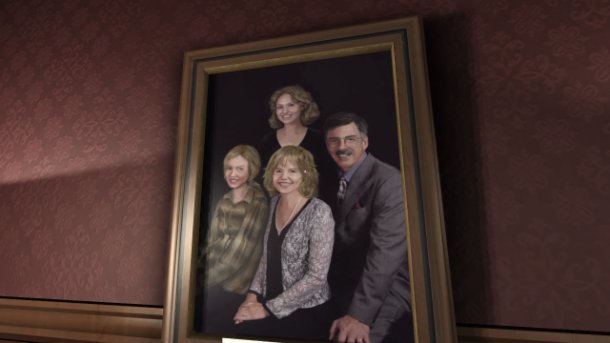

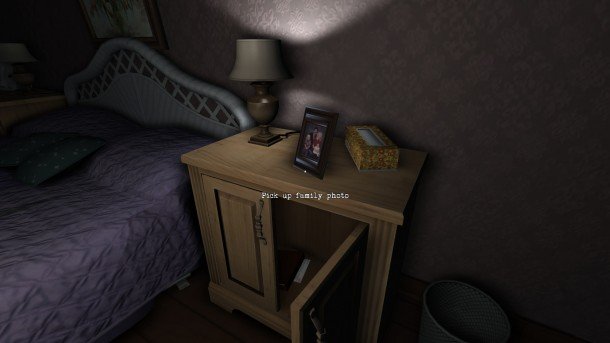

Now they're making something else interesting: Gone Home , a non-violent exploration game which puts the player in the shoes of a mid-'90s girl who has just returned home from abroad to an empty house. As a storm howls outside, she digs through her family's belongings to discover where they are—especially her younger sister, Sam—and what's happened in the time she's been gone.

At the Game Developers Conference last week, I spoke with Gaynor about Gone Home's inspirations and the indie showing at the convention.

PC Gamer: Where did the idea for Gone Home start? What was the seed?

Steve Gaynor: Well, it actually does come from working on the BioShock franchise. I didn't work on the original game, but I worked on BioShock 2 and was the lead on Minerva's Den, and Karla and Johnnemann and I all worked together on that. Then I left and worked on Infinite for a year. And for us, all of us went from a big team on BioShock 2 to a very small team on Minerva's Den...to me going out to Irrational to work on Infinite, which was another huge team.

"It actually does come from working on the BioShock franchise."

And that sequence of contrasts made all of us want to have that small team experience again. And my wife and I—my wife's from Portland and I lived there for a long time—we wanted to move back to Portland. So, I'm very grateful for the fact that Karla and Johnnemann agreed to move up there and start a thing with me, but now we've got three people, and we want to make a game that has those feelings of first-person immersive exploration, discovering story by exploring an environment, and so, we're like, "How can we do that?"

You know, we can't afford to make a whole city. We don't have a character animator. We had to figure out how it's just the environment, and that became this family's house. A house is dense with all this evidence of who these people are and what's happened to them, and we committed to that, and the rest of the creative decisions kind of rolled out of that. The time period and who the characters are were all creative answers to these practical questions of, "How do we make the kind of game we want to make with the team we have?"

The biggest gaming news, reviews and hardware deals

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

So, creative decisions inspired by limitations?

Yeah, limitations, and also like—for instance, we didn't decide we were going to set this in the '90s because we were just like, "Let's make a '90s game." It was, like, "OK, we want to make this game that's about exploration, and being alone in the environment discovering stuff," and if it's set in 2012, all the interesting stuff you're gonna find out about these people's lives is in their e-mail inbox and their text message history. You find Dad's computer and it's not interesting anymore.

So, we want it to be familiar, recent, as believable to our own experiences as possible, so 1995: you might not have AOL yet, you're still writing each other letters, notes for each other. And when we got to that creative decision based on practical problems, it was like, "Alright, well now we have a time period and now we have to commit to it, we have to invest in it and make people believe in that era, because it's serving these other purposes about the kind of game mechanically we want to make."

Playing through it, I think about my mom's house now, and items in it. Like a corkboard with notes stuck to it. I think I might have one in my apartment, but I don't use it. It's a relic.

Yeah, because it's like, "send me a text." [Laughs]

That's interesting—the little things we may not even remember from life in the '90s. It's a more drastic difference than maybe we realize.

It also helps us because we wanted the player to be totally isolated in the house, and for it to make sense why they wouldn't just call the cops or something. So, you know, it's a dark and stormy night, and there's been a power outage, there's a weather warning on the TV, and the phone tone isn't working, and in that era if your land line is down and you got dropped off at the house by an airport shuttle and it drove off, you're stuck there. You can't call a cab or try to call your parent's cellphones...so, there are a lot of different things that we wanted to achieve as far as the atmosphere and experience you have that are a little less plausible in this day and age. You'd be able to solve that problem a lot easier.

You said your work on BioShock influenced Gone Home. How far does that inspiration go?

I mean, the levels are fairly open-ended, right? Like, BioShock does not have linear corridors, and finding the audio diaries is totally player driven. You choose to reach out and listen to these things, and you are piecing these pieces together, so those methodologies were definitely an inspiration to us. And obviously the games that led up to BioShock, like System Shock, System Shock 2, Deus Ex. There's a lot of this open structure exploration and discovering story bit by bit in those games.

So, does Gone Home build to a conclusion? Or do we search around until we feel it's complete and then, "OK, I'm done playing?"

By default, yes, there is a chronological story that you're discovering, and you start at the beginning and you get to the end, and there is an ending when you've fully unlocked all the parts of the house and you've found the last note in the story. That's our out-of-the-box experience—you hear Sam's audio diaries as you find significant objects, all that kind of stuff.

But, we want to support players who want to have a more purist exploration experience, that don't like, for instance, the kind of meta affectation of the audio diaries. It's like, "I wouldn't be hearing that if I was exploring this house," or, "I don't want to have to find the basement key before I can go in the basement," or whatever. So, we have a system of what we call "modifiers," where you can tailor the experience to the kind of expoloration you want to do in a few ways.

What's your opinion on the "is it a game, is it not a game?" debate that comes up with games like yours or Thirty Flights of Loving.

Thirty Flights of Loving was my game of the year last year. So I guess I just call it a game. [Laughs] You know, like...

You don't feel like the distinction matters...

"I'm less interested in 'Is this a game?' than 'Is this an experience that I want to have? Whatever it is.'"

I mean, I understand why there are strong opinions on it, because I think it's totally possible to say, "That's not a game," in a pejorative way that just dismisses it. "That doesn't have value," is basically what's being expressed. And if that's the way someone means it, then that seems like something that's worth criticizing.

On the other hand, if people want to say, "Gone Home's not a game, it's an experience, it's a simulation of exploring a house, it's a story you play, a story you walk through," I don't know. To me, I think the word "game" is broad enough to contain almost anything that requires your interaction to derive the experience from it. You know, because the games in the narrative category in [the IGF awards] this year, there's a broad range in how much input the player has to how they experience the game. But I don't think that makes any of them not games, and I'm less interested in "Is this a game?" than "Is this an experience that I want to have? Whatever it is."

Why do you think interactive storytelling—well, what would you call it? Story exploration?

Our trailer says "A story exploration video game." I think it is interactive, not in as much as it's player-driven story, like creating story through systems or any of that, but all of your discovery of the story comes from choosing to interact with the game and investigate it by touching it and picking things up and examining them, and then the connections are all drawn in your head, not a lot of lore in the game that says, "this happens, then this, and this."

Why do you think we're seeing so much storytelling experimentation now? Is it the practical ability for small teams to make games?

Thirty Flights of Loving is right next door to us [on the GDC floor], it's amazing. Cart Life is a very systemic storytelling thing. And yes, I believe the answer is what you pointed to, that new forms of social media, Twitter and Facebook stuff, allow more people to discover niche stuff more easily, because their friend told their friend and now you've heard about it. So if you're making a niche game...before, most of the potential people who might like it would never find it, but now if you're making a niche game, every person in that niche can become aware of your game, and come out in numbers enough to support it and make it viable.

That's also because of Steam and other digital distribution methods that lower the barriers. The developers don't have to get shelf space and the gamers don't have to go out to a store—you read a review or whatever and just click a link to buy it right now, wait a few minutes, and now you play it. All those barriers to entry lowering, and the avenues of communication opening up, I think you've made way more people feel like, "I can make something small on my own, with a lower investment, that can be sustainable." And so yeah, I think more people are trying because they can.

How do you feel about the state of storytelling in games? Does it need more of something, less of something?

"I think [indie games] will influence the gaming medium as a whole, and that's f****** awesome."

I'm really glad that it is getting broader, that more people are trying to say more things more different ways. We're very lucky to be nominated in the Excellence in Narrative category, first year ever that the IGF is doing a narrative category. If you just even look at that standpoint, if you look at us, 30 Flights of Loving, and dys4ia, and Kentucky Route Zero, and Cart Life, they're telling such vastly different stories as far as subject matter goes, and in totally different ways structurally. They have almost nothing in common.

30 Flights of Loving and Gone Home are both first-person games, but we have a s*** ton of text and voice, and they're totally non-verbal. And we have an unbroken camera perspective that's your experience exploring a place end-to-end, and their timeline is all chopped-up and out of order and you have to piece that together.

I'm just really excited to see that the phenomenon you were talking about, of this growing tide of people trying new things, existing at all when it was harder to be that experimental and get an audience for it before, because I think that the more indie teams and people who are outside the really high-risk multi-million dollar gaming sphere take chances and experiment and find new ways of telling stories, they prove people find this kind of thing interesting. It's viable. I think that will influence the gaming medium as a whole, and that's f****** awesome.

Thank you for chatting with us, Steve. Gone Home will be out later this year, and recently announced the inclusion of music from two '90s riot grrrl bands. You can follow Steve Gaynor on Twitter , and for more, explore our preview of the game from last year.

Tyler grew up in Silicon Valley during the '80s and '90s, playing games like Zork and Arkanoid on early PCs. He was later captivated by Myst, SimCity, Civilization, Command & Conquer, all the shooters they call "boomer shooters" now, and PS1 classic Bushido Blade (that's right: he had Bleem!). Tyler joined PC Gamer in 2011, and today he's focused on the site's news coverage. His hobbies include amateur boxing and adding to his 1,200-plus hours in Rocket League.