Dwarf Fortress dwarves are 'more human than human,' creator says: 'They're allowed to embody bigger emotions. They're allowed to make bigger mistakes. They're allowed to do anything'

Dwarves embody the universal human urge to wade into a flooded tunnel in search of dinner.

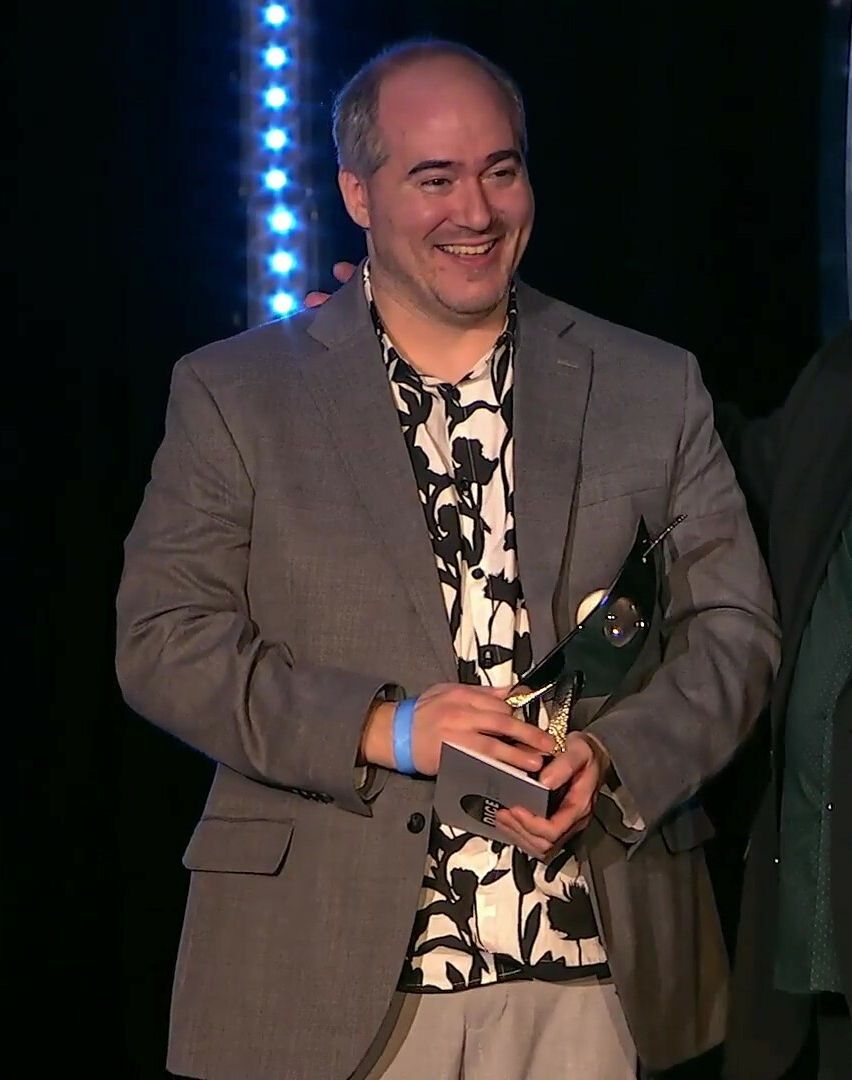

At GDC 2025, I spoke with Tarn Adams, co-creator and lead programmer of Dwarf Fortress, about the past, present, and future of his 23-year procgen masterwork. We talked about how the looming threat of aquifer flooding encapsulates his approach to Dwarf Fortress difficulty and how he's generally bummed about AI. Towards the end of our interview, our conversation turned to dwarves themselves—and to what the stout, stubborn folk add to Dwarf Fortress's emergent storytelling that other creatures can't.

Dwarf Fortress wasn't always about dwarves. It began development as Mutant Miner, a turn-based ASCII game prototype where the player dug for radioactive goo to grow extra limbs and trigger other beneficial mutations. As the game expanded, Adams—along with his brother and co-creator, Zach Adams—grew dissatisfied with the turn-based tempo.

As they shifted the game's design towards realtime simulation, the brothers opted for a change in aesthetic. Having already built D&D-inspired text adventures and isometric RPGs together, Adams said he and his brother "felt more comfortable with fantasy stuff." And if you're making a settlement about subterranean fantasy creatures, dwarves are the obvious choice.

While placing the player in charge of a dwarven caravan was originally a pragmatic decision, I asked Adams if, after two decades, he thought dwarves provide something unique to the Dwarf Fortress experience—beyond being fun to watch bad things happen to. He agreed.

"Dwarves turned out to be fortuitous, because they're sort of like—I don't know why it pops into my head—replicants from Blade Runner. 'More human than human,'" Adams said, quoting the Tyrell Corporation's slogan. "That's a dwarf."

As creatures driven by simulated needs and desires, dwarves in Dwarf Fortress, Adams explained, have gradually become a kind of distillation of the human condition. "They're allowed to embody bigger emotions. They're allowed to make bigger mistakes. They're allowed to be stubborn," he said. "They're allowed to do anything."

To Adams, it's an effect embodied by "dwarfiness"—a term coined by the Dwarf Fortress community to describe the ineffable foolhardiness and mythic melodrama of dwarven endeavor. It's dwarfy to construct an elaborate magma-harvesting scheme to spill lava out on invading armies, just as it's dwarfy to devote oneself to a craft so thoroughly that you starve in the workshop while waiting for material of the proper quality.

The biggest gaming news, reviews and hardware deals

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

"'Dwarfy' the adjective comes up all the time, right? Any time something goes horribly wrong, you're just like, 'Oh, yeah. Fits right into these dwarfy tales,'" Adams said. "There's everything about it, from drunkenness to a very noble hubris. It's all there. Dwarves allow us to experience these different parts of ourselves that, in humanity, you might be more judgmental of."

It's a perfect union of fantasy trope, simulation design, and player empathy. Because we expect a fatal stubbornness from fantasy dwarves, it feels fitting when our fortress inhabitants insist on marching past an invading goblin army to go fishing or descend into a murderous rage when their beloved goblet is stolen. And because they're dwarves, we can relate to those impulses when we might not have the same empathy for another human being who'd follow them.

If, god forbid, Dwarf Fortress was a game about elves, Adams said it probably wouldn't strike the same chord.

"If you were playing an elf fortress, all of these stories would hit different. The antics they get up to, especially when it's a bit buggy or just being weird—I don't think elves would hit the same way," Adams said. "It'd be like 'What's going on with them?' Whereas with dwarves, you're like 'Nah, I know what's going on.'"

Subjecting an elf to life in a Dwarf Fortress feels tragic. Meanwhile, something makes sense about a dwarf wanting to eat dinner so badly that they'll wander through a poison miasma if it's the shortest path to a food stockpile.

"Yeah, it's driven by a singular need. And what are these AI agents but driven by the top need that has to be checked off right now?" Adams said. "It feels right, even when it goes wrong, that they have that sense of devotion. It doesn't work for anything else quite the same way."

Lincoln has been writing about games for 11 years—unless you include the essays about procedural storytelling in Dwarf Fortress he convinced his college professors to accept. Leveraging the brainworms from a youth spent in World of Warcraft to write for sites like Waypoint, Polygon, and Fanbyte, Lincoln spent three years freelancing for PC Gamer before joining on as a full-time News Writer in 2024, bringing an expertise in Caves of Qud bird diplomacy, getting sons killed in Crusader Kings, and hitting dinosaurs with hammers in Monster Hunter.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.