Ken Levine's Judas has a little sister, and her name is Void Bastards

The BioShock auteur has been beaten to the punch.

It's almost exactly a decade since Ken Levine effectively announced the end of Irrational Games, less than a year after the launch of BioShock: Infinite. In the fallout, only a handful of staff were left, quietly working away until the studio's eventual rebranding a few years later.

"While I'm deeply proud of what we've accomplished together, my passion has turned to making a different kind of game than we've done before," he wrote in 2014. "To meet the challenge ahead, I need to refocus my energy on a smaller team with a flatter structure and a more direct relationship with gamers. In many ways, it will be a return to how we started: a small team making games for the core gaming audience."

You can debate how appropriate it is to talk about your own creative needs while waving off dozens of employees—the same staff who had weathered the fraught and demanding development of BioShock Infinite. By the end of the following year, Irrational owner 2K had closed all three of the key studios behind the BioShock series. Perhaps, by the time Levine made his statement, the publisher had already decided that the profit margins on auteur-driven blockbusters were too slim to support a standing team of hundreds—on projects that took half a decade or more to complete.

Whatever the case, Levine stuck to his word, bunkering down with a cherry-picked squad of Irrational veterans to work on "narrative-driven games for the core gamer that are highly replayable". In the month after the layoffs, he delivered a GDC talk about 'narrative Legos', in which he explored possibilities for breaking up stories into tiny pieces and delivering them in different combinations depending on a player's choices. For the most part, though, he and the other survivors on Irrational's lifeboat—now dubbed Ghost Story Games—have remained shtum. Right up until the reveal of their secret project, Judas, at the 2022 Game Awards.

Judas looks both remarkable—its kaleidoscopic scenery chewed liberally by the cast—and remarkably like a BioShock game. Its trailers are distinguished by their surrealist spectacle, a mixture of gunplay and fireballs, and encounters with turrets against a backdrop of early 20th century architecture. There's a presiding sense of disgust that targets humanity's worst impulses—as well as hints of that Lego. With its allusions to temporary alliances among a cast of colourful antagonists, as well as a final decision to "fix what you broke or leave it to burn", Judas may just deliver on the changeable narrative Levine first pitched so long ago.

Yet I can't help thinking he's been beaten to the punch. Since that GDC talk, roguelikes have become dominant, and it's now commonplace for developers to chop up chunks of story and shuffle them into different arrangements across multiple playthroughs. In fact, one such game to do that is Blue Manchu's Void Bastards—in many ways the conceptual twin of Judas.

I can't help thinking he's been beaten to the punch.

Irrational wasn't founded by Ken Levine alone—as the man himself was at pains to point out in the company's closing statement. One co-founder was Rob Fermier, an MIT genius whose career highlights include Age of Mythology. And the other was Jon Chey, who had been a programmer on Thief: The Dark Project. As a trio, they led Irrational to cult success with System Shock 2. And afterwards, Chey moved back home to Canberra, where he set up the studio's Australian division—the two Irrationals working in lockstep for many years.

The biggest gaming news, reviews and hardware deals

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

Like Levine, Chey ultimately chafed against the scale of development at Irrational, resolving to work on smaller projects instead. Unlike Levine, he left Take-Two to start his own indie company, Blue Manchu. Nevertheless, both wound up harking back to the setting of System Shock 2.

In Void Bastards, as in Judas, you're tasked with improving your situation on a dying space station. It's an excuse to revisit the same problem-solving loop that Irrational first developed in 1999. Where Thief taught avoidance through stealth, System Shock 2 leaned into survival horror. Eventually, you knew you'd have to confront the lanky mutants and toxic hazards preventing your progress. With a limited ammo supply and weapons liable to snap in two, it took planning and efficiency to make it beyond the MedSci Deck to freedom.

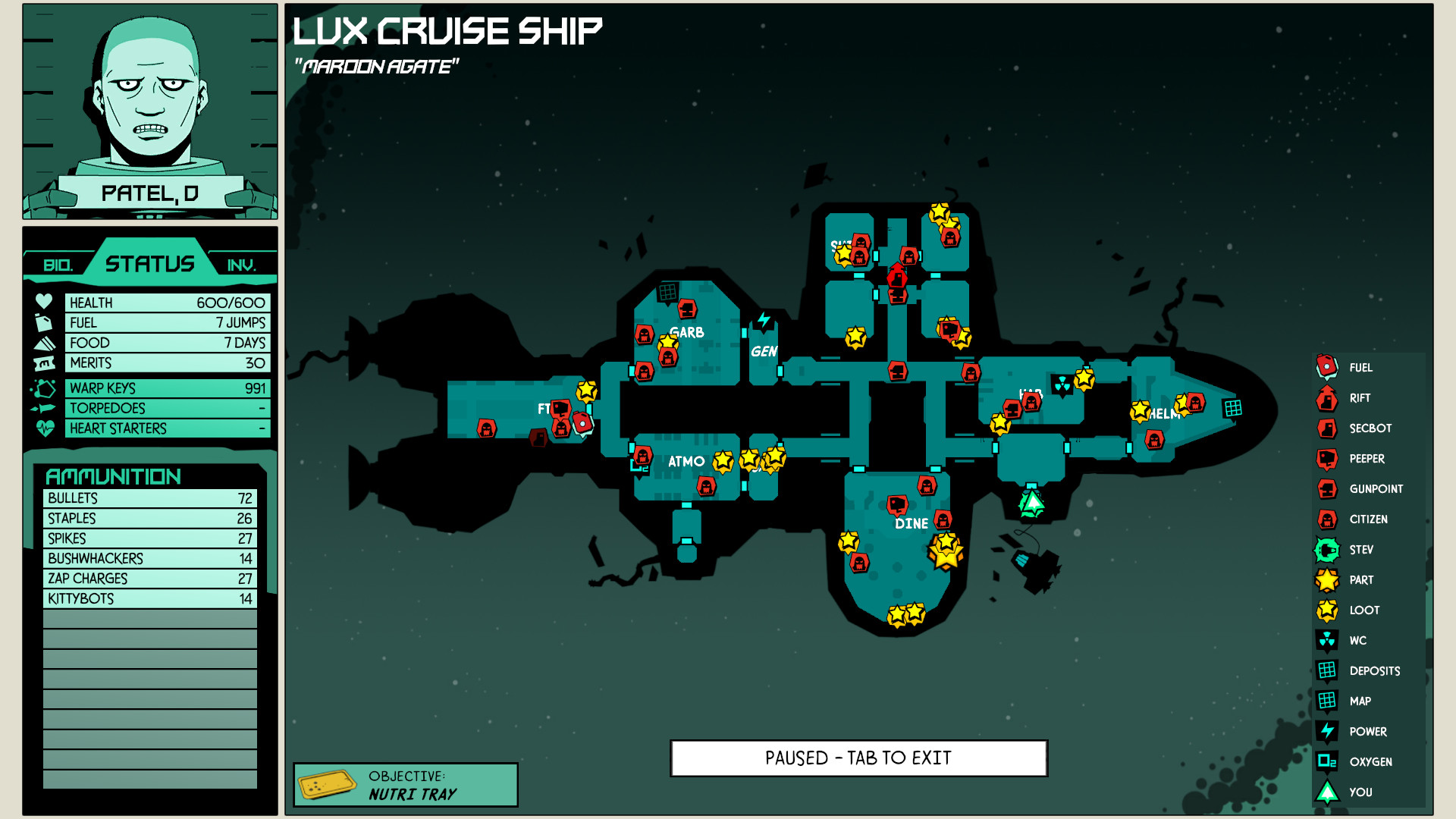

Void Bastards serves up similar problems in bite-sized chunks. As a prisoner whose transport has broken down in a hostile nebula, you pilot a tiny escape pod to nearby wrecks, looking for the parts needed to repair the mothership and the weapons to help you achieve that end. When boarding a haunted spaceship, your goal might be to rifle through every drawer in search of a copy of Surgery 4 Dummies, so that you can upgrade your poison darts for the next mission. But it's never so simple. A nearby camera threatens to awaken the dreaded SecBot, your oxygen supply is already down to five minutes, and there's a mutant Screw stomping around the security room, like a Big Daddy in jackboots.

Added to these quandaries are a set of higher level strategic considerations. As you jet from ship to ship, you're navigating longer-term threats—like starvation, fuel shortages, or the void whales which might eat your craft whole unless you stock up on torpedoes. It's survival horror writ large—a game of resource management played with life-or-death stakes.

Often, horror is only ever a laugh track away from becoming comedy. And as its name suggests, Void Bastards embraces that fact. Its varied enemy types are exemplified by the Tourists—sentient blobs who shuffle around spaceships in tacky hats, complaining about lost luggage. Get too close and they'll detonate with a cry of "Buffet?!".

The story, meanwhile, is a bureaucratic British farce penned by Scottish writer and former PC Gamer contributor Cara Ellison. In its final sequence, you must prevent the space station's self-destruct sequence from activating—by providing its Human Resources computer with a certificate proving a change of address. It's like dealing with your bank, or The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy made interactive.

This kind of knowing absurdity might differ from Judas, but it was as much in Irrational's DNA as System Shock. Just look at Freedom Force, the tactics game which riffed on the overearnest superheroes and anti-communist feeling of Silver Age comic books. Void Bastards, too, is styled like a classic graphic novel—with sound effects transposed to text, like the squelching emitted by Tourists.

Then there's the ghost of Irrational's SWAT 4, which was all about clearing small maps room by room. One of its most important tools was the door wedge, used to lock down areas and prevent armed suspects from emerging on your flanks.

Where Judas goes high budget, Void Bastards went low.

The wedge lives on in the lockable doors of Void Bastards. There's a tense and satisfying delay between hitting the lock button and the ship's authorisation catching up—a few seconds of audio blips and blinking lights in which you can dart through the portal yourself, or simply pray that a pursuing enemy doesn't catch up. It's a crucial method for trapping the aforementioned Screws. Or better still, for sealing them in with a Clusterflack grenade, before peering through the window like a sicko, as the bombs bounce monstrously off every surface.

My hope is that Ghost Story Games is pilfering from Irrational's past with the same enthusiasm as Void Bastards—evoking not only BioShock, but the quirkier, lesser-known games that came before it. Where Judas goes high budget, Void Bastards went low—and showed us an alternate vision that accomplished many of the same goals. With any luck, there's still plenty of Lego left in the bucket for Levine to play with.

Jeremy Peel is an award-nominated freelance journalist who has been writing and editing for PC Gamer over the past several years. His greatest success during that period was a pandemic article called "Every type of Fall Guy, classified", which kept the lights on at PCG for at least a week. He’s rested on his laurels ever since, indulging his love for ultra-deep, story-driven simulations by submitting monthly interviews with the designers behind Fallout, Dishonored and Deus Ex. He's also written columns on the likes of Jalopy, the ramshackle car game. You can find him on Patreon as The Peel Perspective.