Remembering the weird HeroQuest novel that combined Beowulf, Discworld, Dying Earth, and American Psycho

HeroQuest: The Fellowship of Four was a real oddball.

It can't be easy turning a board game into a book, though at least with a fantasy game there are plenty of fantasy novels offering a template to work from. You don't get that if you're asked to adapt, say, Power Grid. Given the task of turning children's dungeon crawl HeroQuest into a book, Dave Morris decided to borrow from four existing templates: the verbose Vancian fantasy of the Dying Earth stories; the epic saga of Beowulf; the comic stylings of Terry Pratchett's Discworld; and the twentieth century nihilism of Bret Easton Ellis.

No, you're right. One of these things is not like the others.

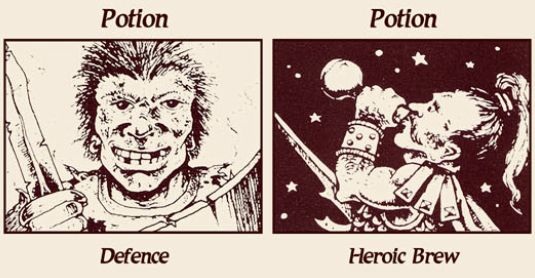

HeroQuest has four heroes, so Morris began by giving each their own chapter written in their own style. The wizard Fortunato casts things like "the Spell of the Extended Instant" and has to memorize spells in advance, just like the wizards of Jack Vance's Dying Earth stories and the D&D class they inspired. Reminiscent of Vance's Rhialto the Marvellous, he's a fop and a dilettante who disappoints his master and describes his financial situation by admitting, "I had made several heroic sorties along the borders of fiscal calamity".

By comparison, the barbarian Asgrim's chapter is refreshingly straightforward, recalling Beowulf, an Old English saga so old we don't know who wrote it. Beowulf famously begins with an Old English word that has no direct modern equivalent: "HWAET." J. R. R. Tolkien, in his day job as an English professor, compared it to the sound of a band striking up before they play and used to begin his lectures on Beowulf by shouting the word at his audience. Morris begins his barbarian's tale with "Attend my words!" and goes on to describe a series of tragic events centered on a great hall and its laws of hospitality, just like Beowulf.

The dwarf, Anvil Delvanbreeks, gets a chapter that's less obviously parallel to its inspiration. Written in first-person, it lacks some obvious quirks of Terry Pratchett, like the digressive footnotes, though it does reflect his colorful dialogue with Anvil threatening to "apply some really creative violence" and comparing saving the world to "that category of Things that Really Express the Futility of It All. You know, no matter how much you do it's never over with … like washing-up." ("I eat straight out of the cooking-pot and that saves all the bother", he goes on to say. "Of fighting evil?" asks Fortunato. "No," he replies. "Of washing-up.")

The real oddity is the chapter from the perspective of Eildonas the elf. To reflect this fey being's alien mindset, Morris writes him like one of the alienated modern-day characters of Bret Easton Ellis. His detachment from mortal concerns echoes their affectless nihilism, and he even shares their tic of calling products by their full name—only instead of referencing brands he's calling a magic sword by its proper name then listing all the ingredients that went into its making like Patrick Bateman describing a business card.

The Fellowship of Four was published just nine months after American Psycho, so it was a very contemporary reference, but it makes a heck of a contrast with the flowery prose of the wizard's chapter that immediately precedes it.

The biggest gaming news, reviews and hardware deals

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

After the heroes are introduced, the dandy wizard, the grumbling dwarf, the honorbound barbarian, and Bret Easton Elvish form an adventuring party and the rest of the story is told in a more traditional heroic fantasy style, with the back half of the book taken up by a choose-your-own-adventure gamebook. Morris would go on to write two sequels, though neither was quite the odd literary experiment The Fellowship of Four was. One was more wizard whimsy, while the other concentrated on the barbarian and put him through a pulp adventure wringer like Robert E. Howard's Conan stories, only without all the bigotry. Both sequels also contained gamebooks at the back, and unlike The Fellowship of Four they included full maps so you could play them in the actual HeroQuest board game.

Avalon Hill has rereleased HeroQuest, alongside several of the original expansions. It hasn't got around to the novels yet and I suspect never will, but I would like to see an idea as goofy as a board game novelization that channels four totally different authors given another chance today.

Jody's first computer was a Commodore 64, so he remembers having to use a code wheel to play Pool of Radiance. A former music journalist who interviewed everyone from Giorgio Moroder to Trent Reznor, Jody also co-hosted Australia's first radio show about videogames, Zed Games. He's written for Rock Paper Shotgun, The Big Issue, GamesRadar, Zam, Glixel, Five Out of Ten Magazine, and Playboy.com, whose cheques with the bunny logo made for fun conversations at the bank. Jody's first article for PC Gamer was about the audio of Alien Isolation, published in 2015, and since then he's written about why Silent Hill belongs on PC, why Recettear: An Item Shop's Tale is the best fantasy shopkeeper tycoon game, and how weird Lost Ark can get. Jody edited PC Gamer Indie from 2017 to 2018, and he eventually lived up to his promise to play every Warhammer videogame.