The making of Cult of the Lamb: 'A lot of the design was trying to encourage the player to be evil'

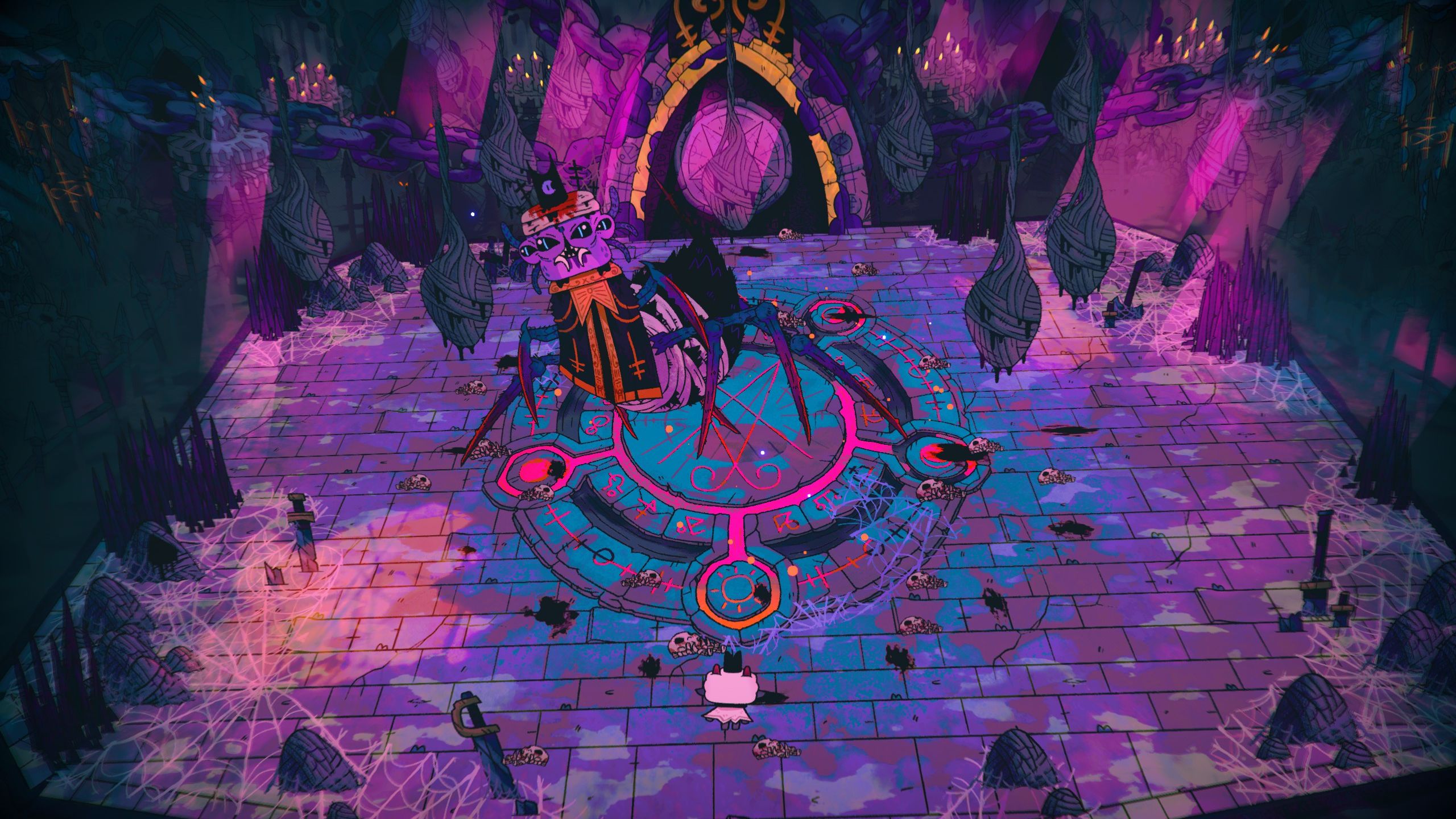

An unusual combination of creepy dungeons and farm-life folk horror made Cult of the Lamb a surprise hit.

In a typical run-based dungeon crawler, at certain points your progress is blocked until you earn a tool like a grappling hook or a bomb that knocks down walls. In Cult of the Lamb, you don't unlock a single boomerang or even a double-jump. Instead, you brainwash more charming woodland creatures into devotion, then unlock the ability to convince them they go to a better place when you sacrifice them for dark power.

Maybe a better comparison is Stardew Valley, which does have a mine full of slime monsters. Still, Stardew's emphasis is on your farm and home life. Its dungeon is just a place where you harvest extra resources. Cult of the Lamb flips that around. The dungeon-crawling is the point, and your home base—a cult headquarters where you eventually train followers to do the farming for you—is where you earn improvements so you're better at killing monsters. If Stardew Valley is a crucifix, Cult of the Lamb turns it upside down. Then draws it on a pencil case beside a row of skulls.

"A lot of the design was trying to encourage the player to be evil," explains Julian Wilton, creative director at Australian indie studio Massive Monster. "Without clearly saying, 'You, go! Go be evil!' But like, 'Hey, if you go sacrifice this guy, you're gonna get a bunch of experience and can level up. Or you can do it another way, but this is going to be the quickest way. So, you know, up to you if you want to be evil.' That's what we're trying to do."

Cult of the Lamb came out in 2022, when Animal Crossing: New Horizons and the extended fervor surrounding it was still fresh in players' minds. Animal Crossing, despite its cutesy aesthetic, was a game where players would decide they didn't like a particular villager then hit them with a net or fence off their home until they moved away. It's not surprising players might give into the satanic whispering of Cult of the Lamb's designers suggesting they mistreat their followers. "Players will do it," Wilton says. "You usually have some guy you don't like. I think that's why it works. I don't like this guy. Get rid of him."

Wilton and the other core members of Massive Monster have a background in Flash games, which suggests one reason why their game so adeptly combines cute art with grotesque themes. The Newgrounds/Kongregate/Armor Games era of Flash games like Dead Baby Dressup or Panda Tactical Sniper or a thousand others provided a template for adorable grossness.

"When we were doing the Flash game stuff it was the peak, it was really popping," Wilton says. "Jay [Armstrong], one of the other directors, he made some battle game kind of thing, and I just took it, changed all the art and then resold it for like 20 grand. I did that in a couple of weeks. It was pretty lucrative and you could make a decent chunk, and I was super young."

Within a decade the bottom had dropped out of the Flash game market. Massive Monster pivoted to games for consoles and desktops, releasing a couple of platformers on Steam called The Adventure Pals and Never Give Up. The first was a modest success, the second not so much.

The biggest gaming news, reviews and hardware deals

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

"With the Flash games, a lot of it was a bit more—not immature, but you didn't really think too much about the story, or the game was about being an egg or something," Wilton says. "Where if you're on Steam and trying to hit the market and actually charge people money for something, you gotta make something that's going to get people excited. Rather than just an egg. I mean, I think that egg game did really well actually. I don't know."

At that point, Massive Monster could have gone in a couple of different directions, but they gathered their eggs into a basket for one more try at the premium indie game model. "We nearly made hyper-casual mobile games," Wilton says. "We nearly made a Steven Universe licensed game. Basically after Adventure Pals, because it wasn't a huge success and Steam games, desktop/console games, were very risky and a lot of work, we were looking at other avenues to bring in some more sustainable revenue or whatever—to run the company a bit more professionally. But I'm glad we took the risk."

God game

Cult of the Lamb went through a lot of changes in pre-production, beginning as a game about people who lived on the back of a flying whale and had to descend into a dangerous environment for resources. At one point it was about a god who could eat their own believers, and then about a demon trying to construct their own Hell. The core idea of a game that was part dungeon crawl, part basebuilder was there, but the precise expression of it came late. During the Hell phase, the team realized they didn't like torturing people and would rather have the option to be nice—or torture them if they felt like it.

Casting the player as the charismatic leader of a cult made everything fall into place. You could take care of your followers by cooking them nice meals and upgrading their sleeping quarters, or you could make them eat a bowl of poop if that was more your thing.

Cult of the Lamb was also developed during lockdown, which perhaps helps explain some of its stranger elements. "We had nothing else to do," Wilton says, "So I'm like, might as well work on it. But maybe some of the dark themes came out of that a bit as well, just watching a lot of horror, getting bored and, you know, the dread of existence at the time."

Wilton describes the development as being "quite iterative." An initial demo was made to apply for a government grant, which was spent polishing it enough to take it to boutique indie label Devolver Digital, which was impressed enough to offer a contract. "I think we had a three-year production schedule with them," Wilton says, "but it turned into four years as it does. They take too long these bloody games, I tell you."

Animal Farm

In the middle of 2022, a Steam Next Fest demo of Cult of the Lamb began appearing on everyone's lists of the best Next Fest demos. A trailer with some gorgeous music and animation helped build interest, and a pleasantly surprising number of preorders followed. "I think that Steam demo did help a lot to boost up those wishlists just before that release window," Wilton says. "I think as a launch strategy it worked super well to build up the hype, but then people don't have to wait that long until it comes out."

Still, the studio wasn't expecting Cult of the Lamb to sell as well as it did, moving over a million units in the first week of its release. "I think the word of mouth definitely helped with it," Wilton says. "A lot of the design of the game was thinking about how we can make it as simple as possible to communicate, even though it is such a big kind of complicated game with multiple genres."

There is a lot going on, with several tech trees and resources like faith and devotion to keep track of, as well as sickness to deal with and sermons to deliver. That meant the dungeons could be kept short—light meals supplemented by plenty of snacky variety in the tasks waiting for you back at the compound. "I don't really like long games," Wilton says. "I think the actual dungeon content, like if you were really good at it you could probably play through it pretty quick. But because you end up spending a lot of time doing what you want—my followers are hungry, I'll go spend time dealing with that—it ends up just taking a lot of time. We're really happy that was the case."

Following Cult of the Lamb's successful release, Massive Monster continued supporting it with sizeable updates. There was a crossover with Don't Starve, whose spookycute 2D characters on a 3D plane presaged Cult of the Lamb's art style, the sex update, which I hope the social media manager was given a raise for publicizing so perfectly, and in late 2024, co-op.

Post-launch support wasn't something the team had to scramble to co-ordinate following the successful launch, but was part of the plan from the point Devolver Digital signed on as publisher. "Actually I baked it in, because I'm a bit of a business boy as well," Wilton says. "I was like, I'm gonna bake this into the Devolver deal in case the game flops."

Jody's first computer was a Commodore 64, so he remembers having to use a code wheel to play Pool of Radiance. A former music journalist who interviewed everyone from Giorgio Moroder to Trent Reznor, Jody also co-hosted Australia's first radio show about videogames, Zed Games. He's written for Rock Paper Shotgun, The Big Issue, GamesRadar, Zam, Glixel, Five Out of Ten Magazine, and Playboy.com, whose cheques with the bunny logo made for fun conversations at the bank. Jody's first article for PC Gamer was about the audio of Alien Isolation, published in 2015, and since then he's written about why Silent Hill belongs on PC, why Recettear: An Item Shop's Tale is the best fantasy shopkeeper tycoon game, and how weird Lost Ark can get. Jody edited PC Gamer Indie from 2017 to 2018, and he eventually lived up to his promise to play every Warhammer videogame.