Gamecamp 4 - an Unconference about games

Last Saturday, nearly 300 people converged on London South Bank University, to attend the fourth Gamecamp. Not a one of them knew what was going to happen.That's kind of the point.

Gamecamp is an Unconference, a term built to eschew the normal conventions of the conference format; the rigid schedules, the crappy hotels, the serious faces. Changing any one of these things intentionally can make an Unconference. This particular brand, though, is about harnessing the chaos of improvisation, and getting people talking.

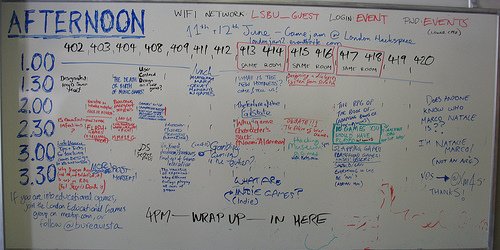

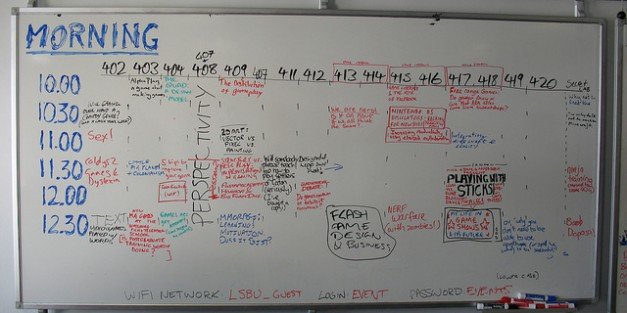

At the beginning of the day, you have 300 people, two white boards, and about ten rooms. Divide up the day into half an hour time slots, and you've got yourself a timetable. An empty timetable. This is the bit where Gamecamp starts to form, and it's probably the most exciting part, if a little bewildering and chaotic.

Because those 300 participants, they're the ones who decide what's going to happen during the course of the day. They grab a board marker, put in some sort of pithy title or even just a topic in a time slot in a specific room, and then they show up at the time and place, and start the discussion. One half hour slot was filled with three letters and an exclamation mark, 'SEX!', before the first session had started. Needless to say the room was packed.

There are few rules, but the ones that are there demonstrate an effort to harness the chaos of giving quite so many people the freedom to do whatever they like. Firstly, this is about games and gaming, but that's the only proviso on topic. Second, you can't have anything prepared. Notes are fine, but a PowerPoint presentation that you've rehearsed in front of the cat is not. Use of the board is discouraged, but above all, the idea is that you shouldn't be giving a talk for half an hour. You should be planting the seed of an idea, and then get people talking.

It sounds very vague and unorganised, and you might imagine that the majority of the talks would end up being moaning sessions about why everyone should be playing obscure indie games instead of the next big triple A thing, but instead Gamecamp becomes something that is constantly interesting, and always varied. Of course you might get one or two sessions that follow what you expect, but there are ten rooms here, and there's nothing that sends more of a message than voting with your feet. Go where you want, and leave if you're bored.

And so, on Saturday, that's exactly what I did. At the beginning of the day the board is always a little sparse, so the first sessions often serve as a casual opener. By which I mean tackling the issue of overworking game designers, and why we need a 'fair trade' equivalent to champion ethical game developers. It's the kind of topic I like to mull over with my morning coffee, because I'm a humanitarian.

The biggest gaming news, reviews and hardware deals

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

Under the title of 'Free Range Games', and being led by Simon Roth, a games developer and student, the idea was that if we better enforced the rights of games developers not to be worked to the bone in crunch time, they'd be better off, and publishers wouldn't have to lean so hard on developers. The great thing about a conversation like this is that a good portion of the attendees at Gamecamp are games developers themselves, and so can present opinions that are informed, as well as valid.

The general consensus at the end of the half hour seemed to be that, while a lovely idea, games needed a crunch time, otherwise they'd never be finished on time. The idea that crunch wasn't all that productive was raised, but there was enough experience in the room to shoot it down. Turns out games developers are quite happy with their battery farm conditions. Or at least, the ones in the room.

There's also no time limit on when you can add talks to the board. In fact, it's actively encouraged to add something after the event has started, especially if it's an idea sparked by a previous talk. It means you get this thematic discussion over the course of the day, with ideas spilling over into one another to create a common theme for the day. Or, when you've got three hundred people, multiple themes that tend to be followed by the same groups of people.

Taking part in talks isn't all you can do at Gamecamp. Along with the board full of sessions, there's also a good deal of boards that you can game on, mostly brought to the event by other attendees. And so, with an hour before the next interesting session was about to start, we picked up a copy of Pandemic and set about failing to save the world from a biological apocalypse.

Gamecamp isn't entirely about sharing ideas. Well it is, but the idea behind it is that it's bringing a huge amount of like-minded people into a very close proximity. The sharing of concepts and perspectives is formalised to some degree, but just being able to hang out with people who think the way you think, for the most part, is incredibly fun. It doesn't matter if you never get to finish that board game, because there's always something to be doing with people, and a discussion to continue past the half hour allocated to it.

Mitu Khandaker lead the next talk, presenting the idea that 'Games are Astronomy', as astronomy concerns itself with extrapolating and elaborating on the tiniest shreds of information we have on the cosmos, to better understand the universe we live in. Astronomers create worlds to look at the big picture, and, Mitu argued, so we created video games to look at ourselves. Simulating life by focuses on the parts that interest us says a lot more about us than the simulation itself. It's an idea I can certainly get behind, although I don't have nearly as many quotes about Carl Sagan to back the words up with.

Hopefully it's starting to become apparent that there's really no limit to the topic of these talks. Moving from game design to game theory to just talking about the game industry and the practical problems that arise, it's hugely unlikely that there'll be any one time when there's absolutely nothing that specifically interests you. And, should that problem arise, there's always the option for starting a discussion on something that does, so long as you're not deathly terrified of public speaking.

So, to continue with the wide variety, the next talk I attended was directed by Tom Jubert, writer on the Penumbra games, as well as doing quite a bit of translation and writing work for various others, both big budget triple A games, as well as indie titles. 'Designing a Dialogue Tree' might not be the most exciting title, but the concept was to identify why dialogue in games currently isn't any good, and what we can do to change it.

It didn't take ten minutes before we ran into the technological wall, using ideas like body language, facial expression and the concept of lying and player intention all creating serious problems for any designer, but at the same time, it meant that suddenly, all those systems identified at the beginning of the session as sub-par became justified and less lazy, more just restricted. A sense of perspective had been given.

By this point in the day, it was a struggle not to want to voice my own opinion, give words to an idea that had been bubbling over most of the day, spurred by different snippets from different talks. And so, placed into the 2:30pm slot, I penned in 'The Failure of the Failstate', which turned out to be an issue that wasn't nearly as clear cut as my mind had framed it.

The idea being that the 'Game Over' screen is a failure of game design because it pulls the player out of the game world, as well as providing a way for players to erase failure from the record. Narrative is all about overcoming and living with failure, rather than having a perfect record, and so we should be able to carry on when we fall down in games, so long as it's a game trying to provide a strong narrative.

Which led to people explaining that, looked at from the perspective of player and the game, you do get those narrative troughs, just not when you look at the only playthrough that matters in term of the end-of-game-save. The topic is probably too big to explain here, but it ran over the half an hour, which can only be a good thing.

Gamecamp is an event that is wholly unique in the Gaming Calendar. There are plenty of talks going on during the year, but there's an energy and level of interaction that you can't find anywhere else. It starts from the moment you walk through the door, to be presented with a Lego Minifig and told to swap out as many parts as you can to make your little guy look like you. Instantly you've got social interaction, laughter, and people trying to persuade one another exactly why they need to have this alien head, without insulting them outright.

There are plans to do another in October, and it's the kind of event that you really get out as much as you put in. It's a day-long discussion about games and any little component that makes them what they are, and, if you want it to be, it's a platform to voice your own opinions, to air that idea that has been mulling in the back of your mind for the past decade. It's time to let it breathe, man.