Foxhole is a persistent multiplayer game where wars can last for days

With 120 players on the field, manning a supply route or keeping watch is as important as building tanks and shooting the bad guys.

I spent three hours playing Foxhole, an isometric massively-multiplayer shooter that hit Steam Early Access today, without shooting anyone. ‘Supplies at location X’ is a constant call to action in the busy player team chat, and so I did my best, breaking down piles of salvage and delivering it to a manufacturing plant, where it was refined and shipped out by an assembly line of other players to one of several forward operating bases keeping our frontline steady. I smashed piles of rubbish with a hammer, walked over to a truck, deposited the rubble, and watched it drive away. I forgot to eat dinner that night.

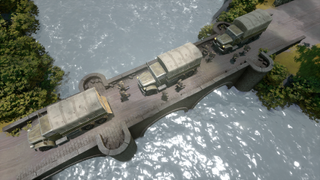

Set in an alternate timeline around the Great Wars, Foxhole pits two teams against one another in campaigns of attrition that can last anywhere between four hours and four days, roughly. With up to 120 people on the same RTS-like map that takes 10 minutes to sprint across, losing ground is easy unless your team is working together to manufacture foxholes, trucks, razor wire, tanks, guns, walls, and sandbags to keep everyone alive and push into enemy territory. More importantly, every FOB needs a steady stream of ‘supplies’, a resource spent to spawn soldiers on location as opposed to minutes away at home base. It’s an ambitious, exhausting game whose scope will excite as many players as it will bore to death.

War changes, ever so slowly

Most firefights end with me on the ground accompanied by a stream of confusion from team chat asking questions about my intent and why I’m such a fool. I don’t know, honestly. I try to shoot the other men, but it’s hard to get a sense of precision and impact when you and the enemy characters are so damn small and all you have is a white line and a cursor, with a range limited by the isometric camera.

Still, weapon fire is slow and deliberate, rewarding players that have a good sense of how to lead their opponent and anticipate their movement. And because you can’t shoot beyond the border of the screen, annoying sniper skillshots from across the map aren’t a thing. I don’t enjoy the confusion of combat anyway, so it’s back to the supply route with me. It’s simple, honest work, and I like the monotony. Plus, right before I left an ally soldier went down and personally asked me to finish them off. It was funny, but also awful, and that’s a potent combo.

On a persistent battlefield that can host wars that take days to complete, it’s sabotage and subterfuge that really get the pieces moving around the board.

Whether I'm on the frontline or carrying dirty metal to and fro, I feel part of a greater cause, like a single unit in a Company of Heroes match whose seeming insignificance will come full circle when the same jerks that told me I don’t know how to shoot (I don’t) run out of ammo and, lo and behold, find some on a delivery truck headed their way—an indirect gift from manufacturing and my blighted, labored hands.

I don’t feel part of a moral cause, mind you. After visiting the frontline again, this time as a passenger in a tank with one of the Foxhole developers—tanks are new, by the way—our tour over the contested bridge and into enemy territory is a short one, punctuated by shelling enemy soldiers into goofy, horrific ragdoll confetti and the quick realization that we wouldn’t win the war overnight. They had defenses everywhere, so to get anything done, we’d need to cut off the head of the snake. It dawns on me—I need to find the enemy James, the guys who can’t shoot, their go-to supply kings, and feed them to the ground. Holding a frontline is only part of the larger battle. On a persistent battlefield that can host wars that take days to complete, it’s sabotage and subterfuge that really get the pieces moving around the board.

Covert ops, aka, the long flank and fuck up

We move under cover of night, and by we, I mean a squad I tagged along with after catching wind of a plot to sneak through a quieter section of the frontline and seize control of or sabotage a small township and manufacturing plant. At night, light drains just enough to make every incidental object look the same. If a soldier holds still, they might as well be a bush or pile of rubble. So we move forward at the will of our CO, who does that rad thing in sleuthy movies where one person moves forward, makes sure the coast is clear, and beckons their friends forward. Hup-hup-hup. Staying off the road is working well for us, and we reach the outskirts of the encampment, which looks abandoned. But as we move forward, shots ring out from behind us. The war just done changed.

The biggest gaming news, reviews and hardware deals

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

Everyone races to cover, and now we’re stuck behind enemy lines, presumably spotted from a watchtower. They'll spot automatically, but you'll also catch players just sitting on a hill, keeping watch the old-fashioned way. Supply networks like the one we’re trying to bust are one thing, but strong communications networks can stop nearly every plan before it starts.

Truly efficient and competitive teams will perform assigned jobs and take shifts over the course of however many actual days it takes to complete a match. This is where some players might call it quits. Someone has to put down their gun and do the dirty work. If that sounds boring, I don’t blame you, but my feet tingle thinking about what a tidy supply operation I could run. It’s the support player’s dream, an endless font of requests for heals, supplies, intel, and ammo. Need some razorwire? I’ll dance for you. I’ll spell your name with the stuff.

Anyway, back to my imminent death. We’re hunkered down behind a few rusted out jalopies, and due to the strict simulated sightlines, I can’t see a damn thing until I peek around the busted rear bumper. Six or so enemy soldiers fade into existence. It appears that we are screwed, truly. They must have moved in another squad behind us to prevent our escape. Being this deep in enemy territory means we’re definitely going to die, which I’m at peace with because damn I’m hungry, but none of us lay down and accept our fate quite yet. It’s possible to let the folks at home base know our situation, and have them arrange a counter-counter measure somewhere else while the enemy team is distracted. That doesn’t happen. One by one, my teammates fall in the process of making a break for it or throwing ourselves at our opponents to distract them, a sacrifice made so others could escape. Without even trying, I feel like I’m roleplaying.

I’m too scared to make a move and stay prone next to some razor wire and sandbags, betting on the bum horse that an elite force of 50 teammates would push sometime soon and pull me out of this mess. No such luck though. I’m a strategic risk. With a finite amount of resources on the battlefield, risking more lives (including whatever weapons, supplies, and ammo the soldiers are carrying) would be a bad move. In honorable, utilitarian fashion, I die for a greater cause. Well, I make a run for it first, right into a tank. The end.

I log off and call it a day. The next evening, I check back in to a completely different state of affairs. The FOB I called home is gone, now in the control of the enemy. Our covert operation was a loud one, and using the supplies our force left behind, I’m guessing our opponents made an immediate push back. But it’s only when I left that things went awry, which might not be directly related, but I like to think I run an essential supply line. My hammer is swift and strong, my trucks are load-bearing and cooler than horses, and my will, unbreakable—until I finally remember to eat. We had quesadillas, by the way.

James is stuck in an endless loop, playing the Dark Souls games on repeat until Elden Ring and Silksong set him free. He's a truffle pig for indie horror and weird FPS games too, seeking out games that actively hurt to play. Otherwise he's wandering Austin, identifying mushrooms and doodling grackles.

Gabe Newell's cult of personality is intense, but a Valve exec who worked with him says his superpower is how he 'delighted in people on the team just being really good at what they did'

One of Valve's original executives shares a very simple secret to its success: 'You can't use up your credibility' by trying to make bad games work