Everywhere isn't a metaverse, it's Roblox for grown-ups

Bring me the Benz!

Sam Houser, one of the driving forces behind the rise of the Grand Theft Auto series and Rockstar North, has a battle cry. Or at least he used to. When things were going wrong, when one of Rockstar's big projects was running into trouble or a problem was particularly intractable, Houser would send up an internal batsignal and plead: "bring me the Benz!"

The Benz being one Leslie Benzies, who began his career at the legendary DMA Design before becoming perhaps the most key figure in the history of Grand Theft Auto. Benzies assembled the team that would make Grand Theft Auto 3 and would go on to direct and produce every single Grand Theft Auto up to and including Grand Theft Auto 5 (and Online), as well as serving as president of Rockstar North. He may not have the name recognition of a Hideo Kojima or Shigeru Miyamoto, but Leslie Benzies is one of the key creative forces in videogame history.

Benzies left Rockstar North in 2014, initially on sabbatical, before his departure was officially announced in early 2016. He ended up in a lawsuit with Take Two over unpaid royalties, settled in 2019, and established several companies including Build A Rocket Boy, the developer of Everywhere. I've focused on Benzies, but Everywhere began development with other senior ex-Rockstar North types.

That doesn't mean Everywhere is an inevitable masterpiece—you can't credit Grand Theft Auto's brilliance to a handful of individuals—but the brains behind Everywhere do have one of the most impressive track records in the industry, and the last project they worked on remains the most successful entertainment product of all time.

Everywhere's development began in 2016, years before the word 'metaverse' became a personal obsession of tech CEOs everywhere and the blockchain began to infest the fringes of entertainment. A lot's changed since Everywhere was just a mysterious name.

Gaming the meta

Two years ago, Everywhere probably wouldn't have been received as another groan-worthy attempt to build the metaverse. And the thing is, Everywhere doesn't really seem like the many other metaverse plays going on, so much as a grown-up take on Roblox. We've all heard of Roblox now, even if we don't know much about it, but for most of its history Roblox was fairly obscure. It first left beta in 2006 and did well enough to be a going concern, but it didn't acquire widespread traction until the early 2010s, becoming a genuine hit by the middle of the decade.

Roblox is a game creation platform and therein lies the appeal: it's endless, ever-changing, and can constantly surprise its users. There's legitimate criticism of the ecosystem Roblox Corporation has built around the platform, which some claim exploits its young user-creators with an unfair revenue split, and more worryingly has been linked to events such as the kidnapping of a 13 year-old girl. It's also recently been in the news in an absurd argument with, of all people, Kim Kardashian.

The biggest gaming news, reviews and hardware deals

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

The company is now trying to position Roblox as having a growing adult audience, pushing back against the perception it's 'just for kids'. It kind of is though, and every time I've dabbled in Roblox the players around me and the kind of games they make seem to suggest that the community remains overwhelmingly on the young side. I can't ever see Roblox as it is becoming a global entertainment platform for adults, and if it does I'll happily eat my words.

Mass effect

Everywhere could be a platform with open elements, in the sense of allowing users to import assets as well as create from pre-existing ones.

This is why Everywhere's pitch makes so much sense to me. The 'user-created and curated entertainment platform for adults' niche, which is so big that niche may be underselling it, is currently woefully underserved. Probably the closest thing that currently exists is the PlayStation exclusive Dreams, which is both a remarkable piece of generative software and also fatally undercut by its limited distribution.

Even were Dreams to come to PC, however, it is an 'artsy' take on what a creation platform should be. It's beautiful and ethereal and people can create the most incredible miniature worlds in there.

But Everywhere is announcing itself with guns and cars and science fiction cities for the same reason that videogame magazines always had those things on the cover. Everywhere doesn't want to appeal to a limited group of creators and experimenters with outstanding aesthetic taste. It dreams of total mass market saturation, aiming to hit that critical mass of player-creators that will make the platform a self-perpetuating destination.

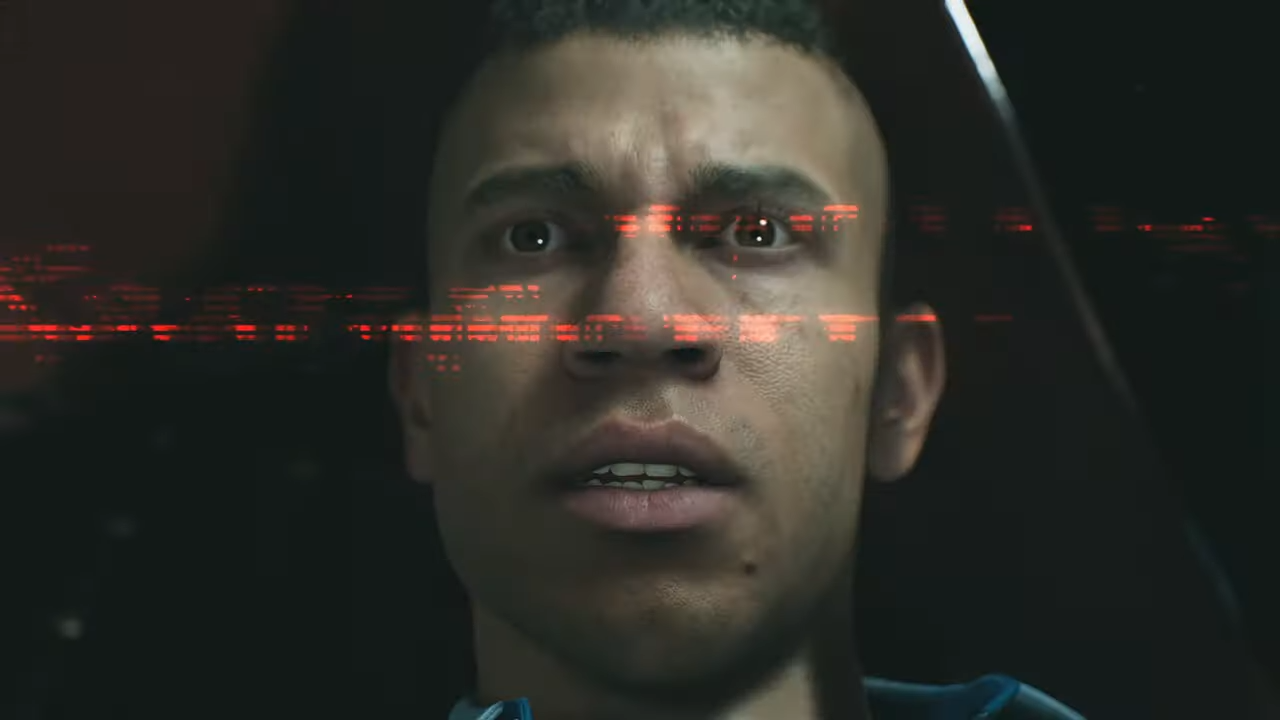

One of the especially interesting aspects of this is how wildly different the art styles showcased in the teaser are. It ends on some typically detailed Unreal Engine 5 faces, allowing you to admire the pores and wrinkles, but the various scenes it showcases look like both different games and that they're built using distinct aesthetics that can clearly be as simplistic or as detailed as desired. I think these art shifts are trying to hint at something very big, which is that Everywhere could be a platform with open elements, in the sense of allowing users to import assets as well as create from pre-existing ones.

This may also explain a recent minor controversy about Everywhere, which came from Build a Rocket Boy advertising some jobs that required knowledge of the blockchain. This led to speculation that tied it to crypto or NFT elements.

"We’re seeing some conversation on NFTs/Cryptos that are prompted by some of our open positions on our website," a representative for the studio wrote on the game's subreddit. "These are research positions, as we do not like dismissing new technologies only because others haven’t found a solution for them yet. We are building Everywhere on Unreal Engine 5, not the blockchain. We are creating a new world for players, where we come together to play, watch, create, share, and so much more!

"We hope this helps clarify some of the speculations around this topic."

Crypt-no?

Hmm. First off: any association with these technologies is at the moment largely toxic for games. Everywhere has been kept under-wraps for so long, and there's been such mystery about it, but it's notable how quickly the studio addressed this concern. Secondly, it can be true that Everywhere isn't being built with blockchain technology at its core, but that it may allow creators to integrate such technologies if they want to.

Sometimes it's interesting to note what a developer isn't saying, as much as it is. Everywhere is obviously going to be a highly social experience with a large multiplayer element. It's also going to be a platform that won't function offline. But the label that its developers won't put on it is MMO—because that would suggest a coherence and a more unified experience that I don't think Everywhere was ever looking to deliver.

Put a gun to my head and I'd guess Everywhere is going to be an incredibly flexible creation platform that arrives feature-rich and with a tonne of assets: but then operates, within certain limits, as an open platform. It'll have a contiguous way of taking small groups of players through different experiences, and briefly crossing them over with over groups in a non-obnoxious manner. Roblox seemed like the more obvious comparison but, now I'm spitballing, I'm imagining a user journey closer to a youtube binge.

The Everywhere site currently has a neat little 3D logo which you can manipulate with your cursor, and a brief FAQ that says it's looking to release in 2023. The official description says it "seamlessly blends gameplay, adventure, creation and discovery." We'll find out soon enough what some of the industry's greatest design talents have been dreaming up all this time, and don't be surprised if, a few years down the line, this thing really is everywhere.

Rich is a games journalist with 15 years' experience, beginning his career on Edge magazine before working for a wide range of outlets, including Ars Technica, Eurogamer, GamesRadar+, Gamespot, the Guardian, IGN, the New Statesman, Polygon, and Vice. He was the editor of Kotaku UK, the UK arm of Kotaku, for three years before joining PC Gamer. He is the author of a Brief History of Video Games, a full history of the medium, which the Midwest Book Review described as "[a] must-read for serious minded game historians and curious video game connoisseurs alike."