Drop into a giant toilet in this mod's inventive Minecraft falling puzzles

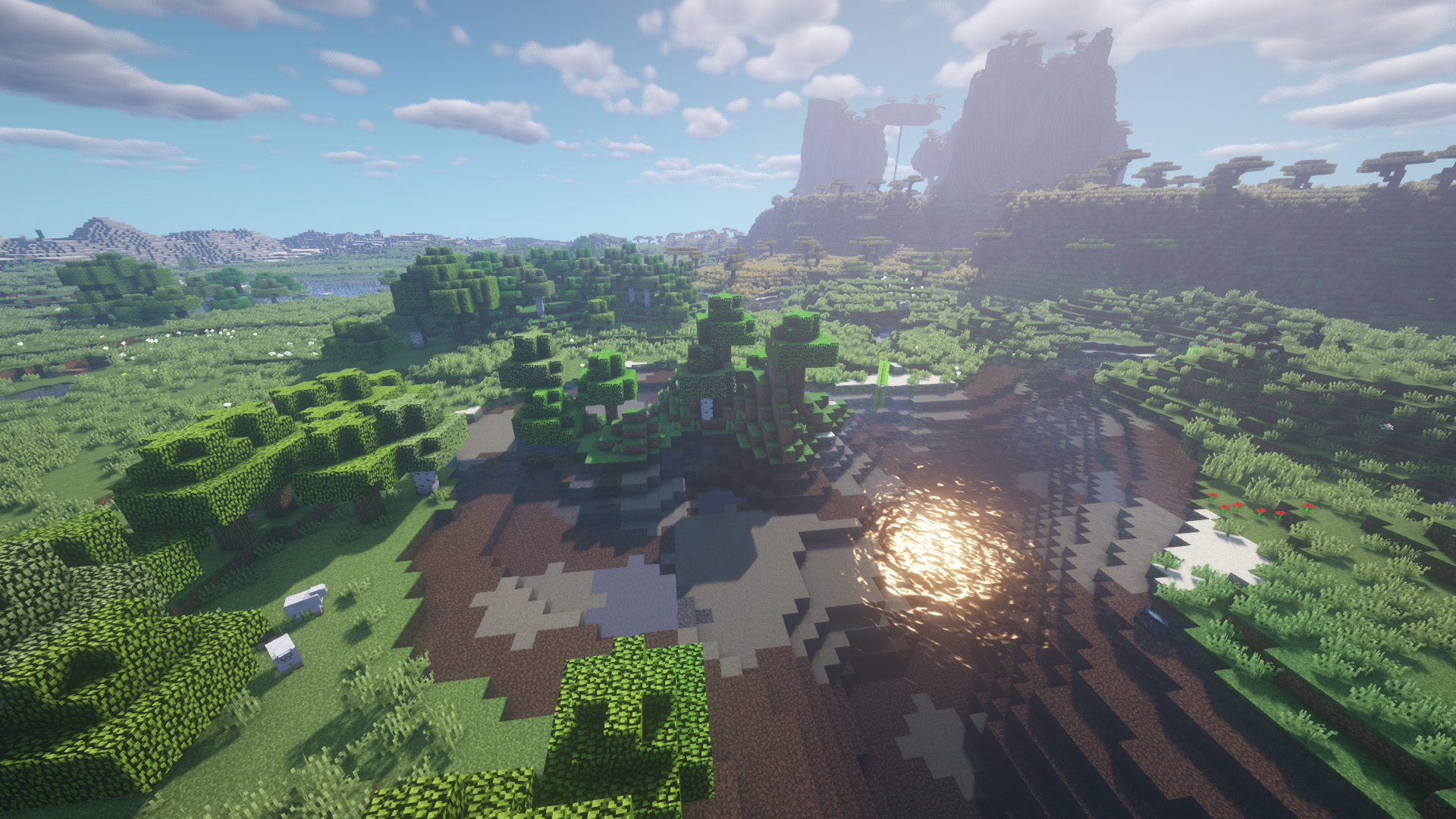

Playful and challenging, Bigre's mod packs create a separate genre within Minecraft.

I stand on a ledge hundreds of metres above the ground, looking out beyond the precipice. Below lies not Arkham City nor Metropolis, but an enormous en suite dominated by a toilet that could double as a skate park. Pink loo roll hangs from the holder, the size of hay bale, and white tiles cover every surface except the ceiling, which extends all the way up to my vantage point.

The aim is to hit the one spot that will safely break my fall—the rancid swimming pool right in the middle of the toilet bowl. Without enough momentum, I’ll splatter all over the mat, which is already patterned in a bloody red and orange, as if the owner were expecting the stain. If I overshoot, I’ll smack my head on the cistern and the smell will be the least of my worries. I wonder if this is what people want when they ask for a modern day Assassin’s Creed.

There’s little point in jumping—up here, I don’t need the extra height. Instead I run at full pelt over the lip, tumbling downward, gathering speed even as I shoot past the seat and connect with the water.

The splash is like the roar of an approving crowd, and I slide happily down the u-bend and out into the next level. This is Minecraft, the way Mojang never imagined it.

The studio is reimagining Minecraft at the moment, as a standalone game named Dungeons. It’s a brave move, taking the least satisfying aspect of Minecraft—combat —and making it robust enough to support the weight of a Diablo-like dungeon crawler. Yet far bolder experiments with Minecraft’s form can be found in its mod archive—inventions that replace the game’s most fundamental goals and leave you with a new appreciation for the flexibility of its toolset.

It’s tricky to imagine a simpler premise than that of The Dropper. You start at the top of a map, and your aim is to reach the bottom alive. Your enemies aren’t zombies or spiders but gravity, and the jutting outcrops that will kill you instantly if you happen to catch them on your long descent downwards.

Often you’re forced to make the jump all in one go, pushing against the air to redirect your avatar as it falls. Your window for readjustment is small and your mid-air movement feeble, and so the most meaningful choice you make is your angle of entry—learning from the bones snapped in your last attempt.

The biggest gaming news, reviews and hardware deals

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

Fall guy

The modder Bigre is the master of this peculiar genre, and though several years old, the designer’s maps still stand as its high point. As with the toilet bowl, Bigre’s landing strips are usually tiny and precise, distant dots representing safety in a sea of pain. Making a touchdown is like threading a camel through the eye of a needle at 100mph.

The modder’s genius is in repurposing the furniture of Minecraft’s survival mode as safety cushions: water can save a life from any height, thanks to the game’s mercifully incomplete simulation of physics, as do webs, which slow you to a gentle descent like sticky parachutes. If you’re lucky enough to brush up against a vine—the same found naturally generated in jungles and swamps—then that too will absorb your momentum, and even let you climb back up, adding another element of verticality to Bigre’s more complex, multi-jump creations.

Success, when it comes, is so unexpected as to be surreal. I feel unsteady on my legs, the way I imagine Olympic athletes do in the seconds after pulling off the feat they’ve trained for, and stare upward at the assault course of blocks I’ve just fallen through. This is The Dropper’s reward. Bigre’s maps are built not just for function, but as art pieces. Like Minecraft’s procedural landscapes, they have an impressionistic character that means they make more sense when viewed from a distance. More frequently than not, the real shape of a map doesn’t make itself known until after the drop, when you can see the picture in its full, holistic glory.

Some are abstract spirals, helter-skelters made to turn the mind inside out as they pass by at speed. Others are riffs on more conventional Minecraft settings—Mine is a criss-cross of trundling carts and industry that recalls Isengard (a subject Bigre would return to with a plummet off the side of Saruman’s tower in The Dropper 2). Another early map finds you zipping between trees in a forest flipped onto its side, before plunging into a vertical lake. It’s where Bigre seems to find the greatest inspiration, playing with the scale and angle of everyday scenery, twisting the mundane into thrilling encounters with gravity.

The toilet bowl forms part of a multi-level experiment in domesticity which reduces you to the perspective of a Borrower. The very best is a sidelong kitchen that encourages you to move ‘step by step’, abseiling without a rope—hopping from the counter edge onto the blade of a chopping knife, and then drifting across a full sink onto the relative safety of the drying rack. The joy of these levels are the regular adjustments your brain has to make just to keep up with what’s in front of you. Bigre’s scenes are packed with details even in the places you can’t reach, seemingly built for their own sake—the magnetic letters on the fridge door, and the portrait of Minecraft protagonist Steve hanging impossibly on the top wall. They make you wonder what’s beyond the front door, even though good sense suggests it’s just the skybox.

Drop box

Minecraft skins: The best new looks

Minecraft servers: Join new worlds

Minecraft commands: All cheats listed

Minecraft mods: How to go beyond vanilla

Minecraft shaders: Let there be lighting

Minecraft seeds: Fresh new worlds

Minecraft texture packs: Transform the game's look

Despite the craft, The Dropper always feels like the work of a Minecraft player, rather than an artist merely working with the cheapest toolkitDespite the craft, The Dropper always feels like the work of a Minecraft player, rather than an artist merely working with the cheapest toolkit available to them. One level is made up of a series of flaming portals, each divided into four squares. Pick the wrong route and you’ll crash and burn. Pick correctly and your flames will be extinguished by water blocks on the other side. It’s like Takeshi’s Castle without the safety regulations.

Another late-game creation positions you opposite a map of a road, winding through countryside. It’s really a guide for your own movements. You have to mimic its twists and turns as you fall through a waterfall made up of Nether portal blocks. The portal takes time to do its work, and the goal is to teleport before you hit the ground. It’s the kind of ingenuity that could only come from a close understanding of Minecraft’s rules, and tests the limits of its materials.

Much less showy but equally impressive is the engineering of the corridors that take you between setpieces. Levers shunt the floor sideways, flinging you into the next level like a paratrooper. And just as you’re getting used to that slick bit of pistonry, Bigre reverses it—opening the ceiling to let a staircase of sand fall into place instead. It’s not just the technical prowess you feel but the care of the creator lavishing love on areas long past the point where it would make economic sense to do so.

There’s so much of Bigre in this game that you start to wonder if the spaces you fall through are those from the modder’s real life—if the PC modelled for the bedroom map is the one the mod was designed on. Maybe Bigre, too, sat on the edge of that toilet bowl, contemplating a dive into a project built for its own sake. It remains a testament to the power of modding as individual expression.

Jeremy Peel is an award-nominated freelance journalist who has been writing and editing for PC Gamer over the past several years. His greatest success during that period was a pandemic article called "Every type of Fall Guy, classified", which kept the lights on at PCG for at least a week. He’s rested on his laurels ever since, indulging his love for ultra-deep, story-driven simulations by submitting monthly interviews with the designers behind Fallout, Dishonored and Deus Ex. He's also written columns on the likes of Jalopy, the ramshackle car game. You can find him on Patreon as The Peel Perspective.