Brian Fargo, Josh Sawyer, and Gordon Walton on the history and future of RPGs

Brian and Josh, you've recently made RPGs that hearken back very deliberately to an older game. That whole first wave of Kickstarter stuff was, ‘Remember the shit you really loved? No one’s making it anymore. Let’s do that again.’ You’re working on new games now. What are you trying to bring to a PC RPG in 2016? I know your games are still rooted in the past, but what can you do to push the genre forward on the PC this year, next year, the next couple of years, that you couldn’t do before or weren’t doing before?

JS: I’ll say that for me, no matter what the platform is, I always want to push more reactivity in choice and consequence, because for me that’s the heart of an RPG. In terms of moving genre conventions forward, I think that in the 2000s—I’ll blame this a little bit on consoles—but the desire to reach a really big audience I think led some developers and publishers to believe that you can’t have a challenging experience, it has to be super-duper accessible and has to be super-duper easy. And I think you have to consider a bigger audience, but I strongly believe, and I think that we’re doing it with the games that we make, you can make things more accessible to people, easier—we don’t need to make UI like we did in the late ’90s or in the ’80s, we can improve the UI, we can make systems more transparent—but still have really strategically and tactically challenging systems that people can really dig their teeth into.

People really want to crunch numbers in a really hardcore tactical challenge that also allows for people who are like, ‘Hey, I like fantasy games, I’ve never played an RPG before. If I put this on easy can I get through it and still have fun while engaging with the gameplay systems?’ I think we can do a better job of that. It doesn’t have to be super-duper simplified, and it doesn’t have to be insanely complicated so only people who make their parents call them 'General' can get through this.

I always want to push more reactivity in choice and consequence, because for me that's the heart of an RPG. - Josh Sawyer

I don’t even want to say there’s a middle ground. We can design mechanics for a range of players to satisfy a lot of expectations, and that’s what I want to do. I want the super hardcore people to really enjoy that experience but I also want people that are more middle of the road—I hesitate to say ‘casual’ because I think there’s a certain amount of crunchiness to RPGs that is a little intimidating for people that really are casual, but I think there’s a bigger range that we can reach out to and we can improve the experience for.

GW: I think also, the audience is so large that the trick is to not make a game that’s for everyone. The trick is to make a really great game for some people that’s a big enough audience to make it work financially. So as a player you don’t fall into a giant bucket of a whole zillion people. You have aesthetics and needs that are narrower than that. A game that’s really gonna make you excited is probably not gonna excite a whole bunch of other people.

So that’s what’s he’s speaking to—it’s not that we don’t want to be accessible to everyone. We know that everybody’s different, and there are groups of people who want harder, more hardcore experiences, which is what we’re building. We’re going back down the evolutionary tree to some place that isn’t growing anymore and saying, ‘Hey, let’s try that. Let’s try to do something hard and interesting for a subset of players who are really gonna dig it, rather than try to make a game that’s for every single human in the world.’

"That’s one of the nice things about Kickstarter. We know we’re making games for a niche, and that's okay." - Josh Sawyer

JS: My first role-playing game was Bard’s Tale [Ed. note: Fargo was a writer on Bard's Tale and founded its developer Interplay]. I was blown away. I saw it at a public library, I was playing it on a Commodore 64. I was like, ‘What in the world?’ and I was amazed by it. But then I really dove very heavily into tabletop role playing and DMing and running games, and I think that’s where a lot of my desire is. I would play with groups of people from hardcore, really experienced folks to guys that, you know, they read fantasy novels and they’re kind of interested. And as a DM, trying to make the game fun for people—I don’t want to write dialogue for people that don’t like dialogue. If you don’t like reading, don’t play Pillars of Eternity. If you don’t like combat—

The biggest gaming news, reviews and hardware deals

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

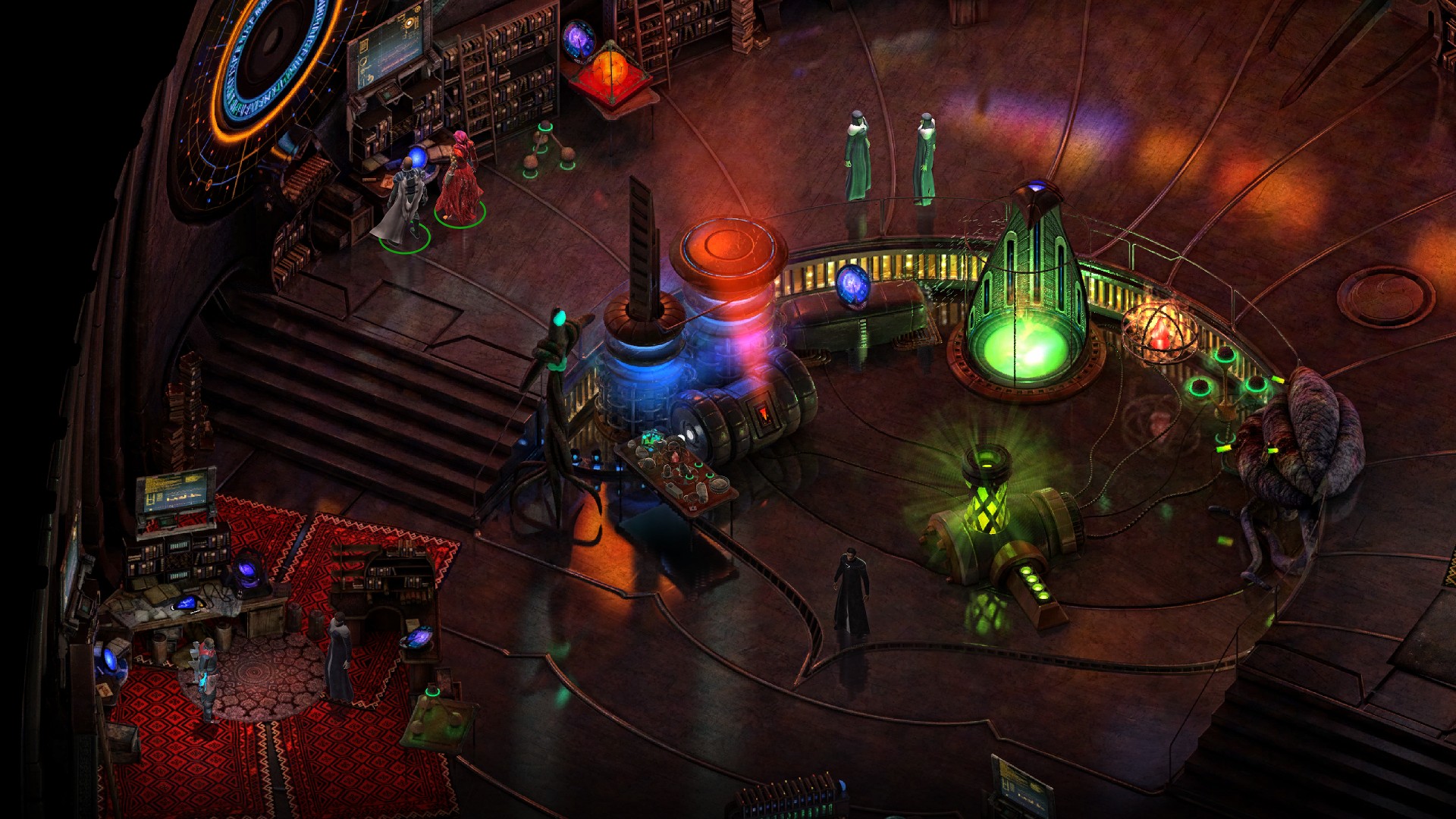

BF: And do not play Torment.

JS: Yeah, don’t play Torment. If you don’t like this kind of tactical combat, even on the easiest setting, don’t play this game. You’re not gonna like it. But if you have a group of people that are like, ‘I love fantasy, I like these conventions, and I like number crunching and stuff like that,’ you can target things for that. We don’t have to try to make games for everyone, and I think that’s one of the nice things about Kickstarter, that we know we’re making games for a niche, and that's okay. That niche is probably larger than it used to be back in the day, but there’s still a range of experiences that we can accommodate.

At this point, Gordon has to leave for another appointment.

The Witcher 3 and a couple other games last year set this bar, I felt like more than any other year really breakout, successful games were massive open-world games that cost a billion dollars to make and an incredible amount of man hours. Witcher 3 is a massive game, Metal Gear Solid V is a massive game, GTA V came out on PC and next-gen consoles and was huge. Do you think that’s kind of where the AAA is going? Are they just gonna keep going bigger and bigger and bigger?

JS: I’m seeing lots of smaller, more contained experiences that appeal to people who say, ‘I only have a little bit of time but I want a really deep, rich, but short experience.' And you’re gonna see the giant games. So if you’re talking about AAA, AAA is going to the big stuff for sure, but there’s a whole palette of games now. What I think is so cool right now is, I was getting bummed out in the 2000s because it’s like, ‘Well, I guess no one wants us to make anything on PC.’ Mobile wasn’t really that established, and it was kind of like, ‘Well you have a few console choices,’ and this sucks. And budgets were real fixed, and so when you talked to publishers, it was really hard to have conversations about doing certain types of games around certain budgets because they want a certain ROI, and it’s just bullshit.

But now, obviously, crowdfunding, we love that.

BF: Yeah, changed everything.

JS: But also, I’m friends with some of the folks at Fullbright, up in Portland. They made Gone Home, they’re making Tacoma. It was a four-person team, now it’s an eight-person team, but there’s a lot of companies out there that are doing these smaller games, either PC focused or mobile focused. There’s a lot of diversity. And yeah, AAA will keep pushing for these big open-world experiences, because it’s fun to fuck around. That’s the thing that’s so awesome about these big open worlds, screwing around is always gonna be pretty fun as long as the core mechanics are good. But I do like that there’s a much wider variety, and I think that also the very tightly scripted kind of stuff, I’ll say I’m not gonna cry if that stuff goes away, because I like the more open stuff. It’s just more enjoyable to have freedom. I mean, that’s kind of the whole vibe of the games that I like to work on.

BF: I think we hang our hat on freedom, very much. Even in our games, they’re narratively deeper than the sandbox games, and I think that people will swing back and forth on that stuff, because there’s a price to pay, typically speaking, when you go for that more open stuff. Now, if you’re Rockstar and you have unlimited funds, different conversation, but we tend to go for a deeper cause and effect in our games we do than more open-world stuff. And I could see where people would enjoy the open world because of the immersiveness, change anything, do what you want, but on the other hand I think they experience some of our stuff and go, ‘Wow, we like this cause and effect. It’s meaningful. It goes more than one level deep.’

So I think I could see people swinging back and forth with it. I don't think it’ll go one way or the other. It’s hard to put a truly open-world game and have the same vertical integration that we have with our cause and effect. I have things where you do it in the first hour of gameplay and it affects it on the 90th hour. One little conversation has ripples later. For the guy that had that happen, they loved that.

JS: Oh, of course. It’s so good.

BF: You love that the world is genuinely affected, being affected, by what you do. That’s the biggest turn on to me, and so there’s a trade.

JS: I’ve only put a couple of hours into The Witcher, but, everything I’ve seen of it and know about it, they struck a really awesome balance. Obviously Geralt is a very established character, he’s from the books, so there’s a lot to draw on to make a very strong story, but they still do have lots of choice and consequence, and lots of freedom. So that stuff I think is really cool, when there’s a really nice balance between the rich storytelling narrative stuff and also a lot of reactivity.

BF: I get bored when it’s like, ‘Go get five rabbit pelts.' I don’t want to be doing much of that. I don’t find that interesting. I’m gravitated towards people and conversation, communication and motives and psychology, philosophy, that’s what I want to be dealing with, not rabbit pelts. And not that we’ll have none of that, but we typically don’t do that in our games.

JS: It’s just not engaging for a lot of people, and I think that when you make a single player experience like that, you want people to feel invested. I think one of the things that makes choice and consequence work is when you get that sort of agony, I always use the term ‘agony’ for it, where you’re like, ‘Do I want to do this or do I want to do that?’, and, 'I think something bad is gonna happen if I do this, but I don’t want this bad thing to happen. Ah shit,’ and it’s kind of bittersweet. I think the best experiences, like the end of Fallout was a really good one, where you’re like, that was such a great ending, that sense of, you accomplish some good but some stuff doesn’t go well. And I think to do that, it has to be more interesting than, ‘Hey, can you go get five pelts,’ because there’s nothing at stake, really. You want people to be invested in the characters and the conflicts and the psychology.

BF: We have so many interesting things going on in our games that we don’t need to keep you busy getting pelts, right? It’s not like, ‘Boy, if we only had ten more hours of gameplay.’ That’s not a problem. We don’t need to buffer it out by any way, shape, or form.

Wes has been covering games and hardware for more than 10 years, first at tech sites like The Wirecutter and Tested before joining the PC Gamer team in 2014. Wes plays a little bit of everything, but he'll always jump at the chance to cover emulation and Japanese games.

When he's not obsessively optimizing and re-optimizing a tangle of conveyor belts in Satisfactory (it's really becoming a problem), he's probably playing a 20-year-old Final Fantasy or some opaque ASCII roguelike. With a focus on writing and editing features, he seeks out personal stories and in-depth histories from the corners of PC gaming and its niche communities. 50% pizza by volume (deep dish, to be specific).