Boxes, feelies, and the good old days of PC gaming

Image via The Infocom Gallery

Consider the box. A humble holder of stuff. Usually (but not always) cardboard and cuboid, and alas, often held in a certain kind of dismissive contempt in this era of digital delights. They're still on shelves, for the benefit of those who can't or won't download their games, but they're pissy little things: a cheap DVD case, with a lazy swipe at cover art—"angry man with gun," again and again and again—and a half-page insert explaining how to shove the disc into the machine, at which time it will get most of what it needs from Steam anyway.

But there was a time when the box was more than just dumpster stuffing. When it contained not just the entirety of the game, launch-day bugs and all, but the things that brought them to life in ways that digital just can't replicate.

The loot, the swag, the tchotchkes, the feelies, the stuff that made it all real, and demonstrated to the outside world—should any member of the outside world happen to stumble into your room—the depth of your dedication to these wonderful worlds and adventures that came inside a humble cardboard box.

Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy

Image via MobyGames

Infocom produced a pile of great text adventures in the first half of the 80s, but what it's really famous for are the "feelies," which were basically roided-up cereal box prizes that came with every game. They often provided a bit of background or early direction, but some of it was just ridiculous window dressing, like the official Palm Tree Lounge swizzle stick that came with Hollywood Hijinx, or the real, live, burn-your-house-down book of matches from the Frobnia National Railway in Border Zone—something that no sane publisher would dare to do now.

The best of the bunch has to be Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy, because its feelies so perfectly reflected the sheer insanity of the game and the book that inspired it. The "Don't Panic" button was relatively mundane, as were the orders of destruction for both Arthur Dent's house and the planet Earth. But there was also a packet of pocket fluff—basically a bit of cotton—along with Peril-Sensitive sunglasses (utterly opaque—put them on and you can't see a thing) and my favorite of the bunch, a small bag that by all appearances is completely empty, but which in reality contains a microscopic space fleet, so small as to be entirely invisible to the naked eye. But it's in there. Really. Of course, there's also no tea.

Ultima Underworld

Image via eBay

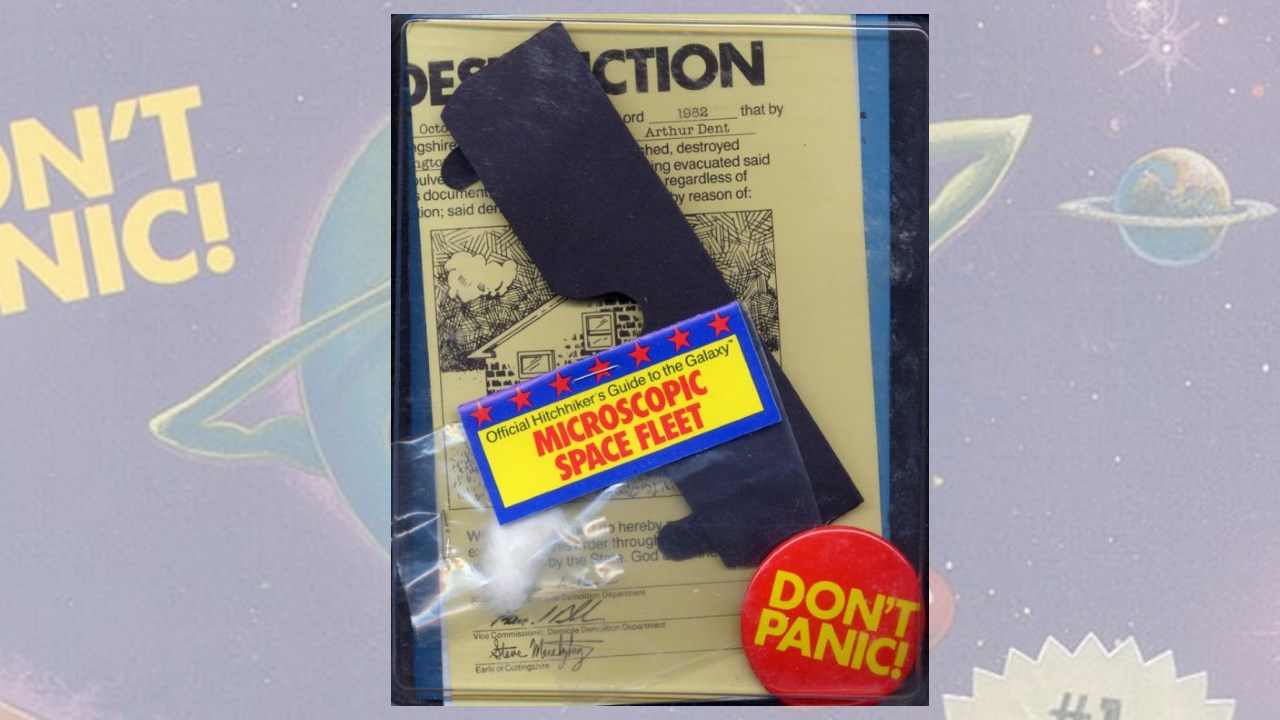

Just about all of the Ultima games were wonderfully well-loaded, but Underworld stands out for a couple of reasons. First is that it's not really an Ultima game at all. The name was slapped on and the Avatar story worked in to take advantage of the strength of the Ultima name, which at the time was a world-beater. It also remains, to this day, the single-best "dungeon simulator" ever created.

The centerpiece of the Underworld package was the set of small, metallic, and dangerously easy-to-swallow Runestones that came in a cloth drawstring bag, replicas of the in-game spellcasting stones. (I purchased a copy of Ultima Underworld on eBay years ago, but the runestones were missing. I'm still mad about that, and still looking.) The box also included a gorgeous hand-drawn map of the Stygian Abyss, on paper rather than cloth (just about all the Ultima games came with cloth maps) and the Memoirs of Sir Cabirus, a history/hintbook written by the founder of the Underworld.

Magic Carpet

Magic Carpet the game is noteworthy for a few reasons. Its fully 3D, destructible-world gameplay was astounding, especially if you had one of the hot new Pentium processors that could really make it snap. Looking back from a historical perspective, it also signaled the end of the golden age of Bullfrog.

Magic Carpet the box, on the other hand, was a little less impressive. In fact, the only thing of note besides the game disc and manuals was a pair of 3D glasses. Because the game could be played in 3D! The effect wasn't great, mind you, particularly if your eyes had a habit of going wonky after too much Red vs. Blue on your face, but if you could find the sweet spot and keep your head still, it worked! Believe me, in 1994 this was hot stuff. And their practical value went well beyond the game; whenever I need a pair of 3D glasses (which, admittedly, is about once every two or three years), I get out my Magic Carpet box. Those glasses are quite possibly the most useful piece of tangentially gaming-related crapola I own.

Secret Weapons of the Luftwaffe/Their Finest Hour: TBoB

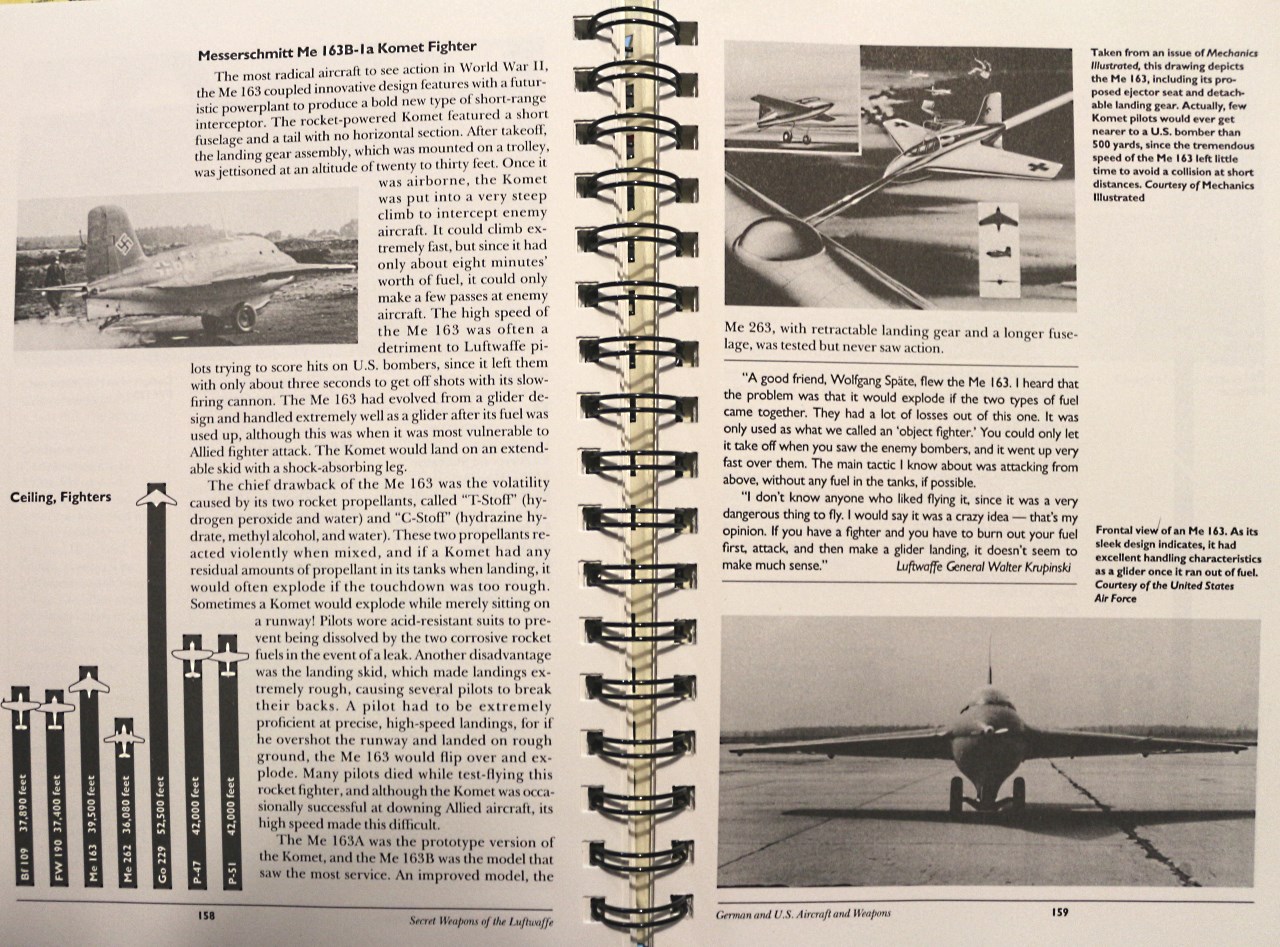

Proper instruction manuals are deader than the game box, but even in the days when they were standard equipment, Lucasfilm's Secret Weapons of the Luftwaffe was a standout. It's a 224-page opus (and that doesn't count the fold-out maps in the back) and includes a lengthy historical overview of the air war over Europe, an interview with Professor Williamson Murray of Ohio State University, plus history and technical information on every plane in the game, sections on weapons and tactics, and all sorts of historical trivia.

But the best bits come from USAAF and Luftwaffe pilots who actually contributed to the creation of the manual. (Luftwaffe ace Walter Krupinski, later the commanding officer of Germany's post-war air fleet, has a Mobygames credit.) It's not really useful in the strictest sense—Second World War veteran Captain James Finnegan doesn't have much to say about how to save your game—but the inclusion of historical context made the game feel so much more real and weighty than the comic book-style cover lets on. It's also tremendously fun to read.

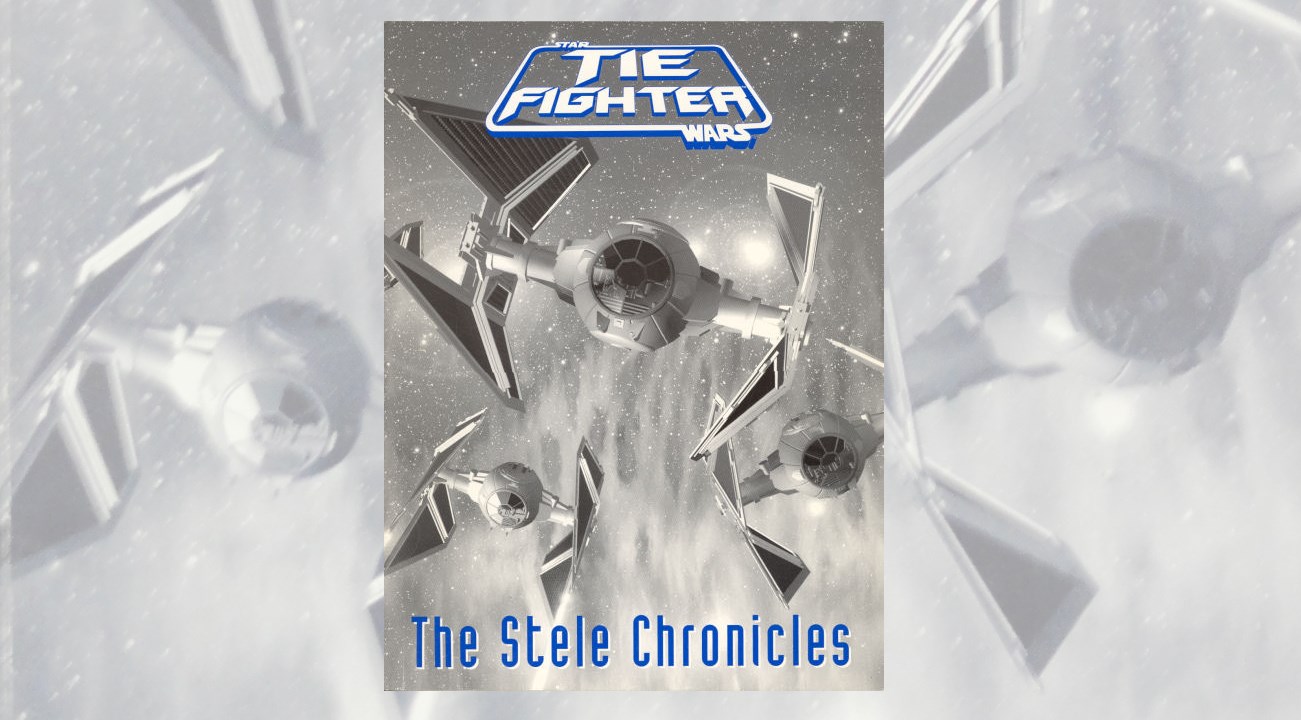

TIE Fighter

TIE Fighter accomplished the impossible: It made the Galactic Empire into the good guys. It pulled off this remarkable feat by way of the Stele Chronicles, a novella about the adventures of Maarek Stele, a backwater bumpkin who becomes one of the Imperial Navy's greatest pilots. He makes and loses friends, finds a worthy mentor in a superior officer, struggles against treachery, and grapples with his conscience about the Empire's heavy-handed methods in the face of his belief that the peace and order it brings to the galaxy is worth fighting for.

It's a gripping story, and it also serves as the game manual, incorporating the instructions into the tale of Maarek's training. The novella was written by Rusel DeMaria, famous among gamers as the author of numerous strategy guides and other game-related books. He wrote a similar tale for the Rebel side of the conflict called The Farlander Papers, named after X-Wing hero Keyan Farlander, which was included with the diskette-based Limited Edition release of X-Wing. But TIE Fighter was better.

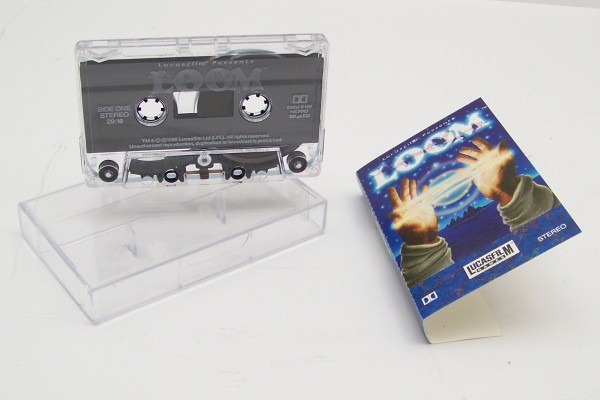

Loom

Image via Video Game Auctions

The great Lucasfilm game Loom was built around the concept of music as magic, and so the inclusion of a cassette tape in the box made perfect sense. But it wasn't a soundtrack. It was a 30-minute audio drama, the sort of thing you'd listen to on the radio in the 30s and 40s, that served as a prequel to the game. (I'll thank you to not ask me what a cassette is. Or a radio.)

According to Wikipedia, the Loom audio tape was the first commercial cassette to use Dolby S noise reduction, a technology that failed to catch fire with mainstream audiences because it launched at roughly the same time as the new, noise-free compact disc format. It's kind of an ironic bit of trivia in a story about the past glories of game boxes.

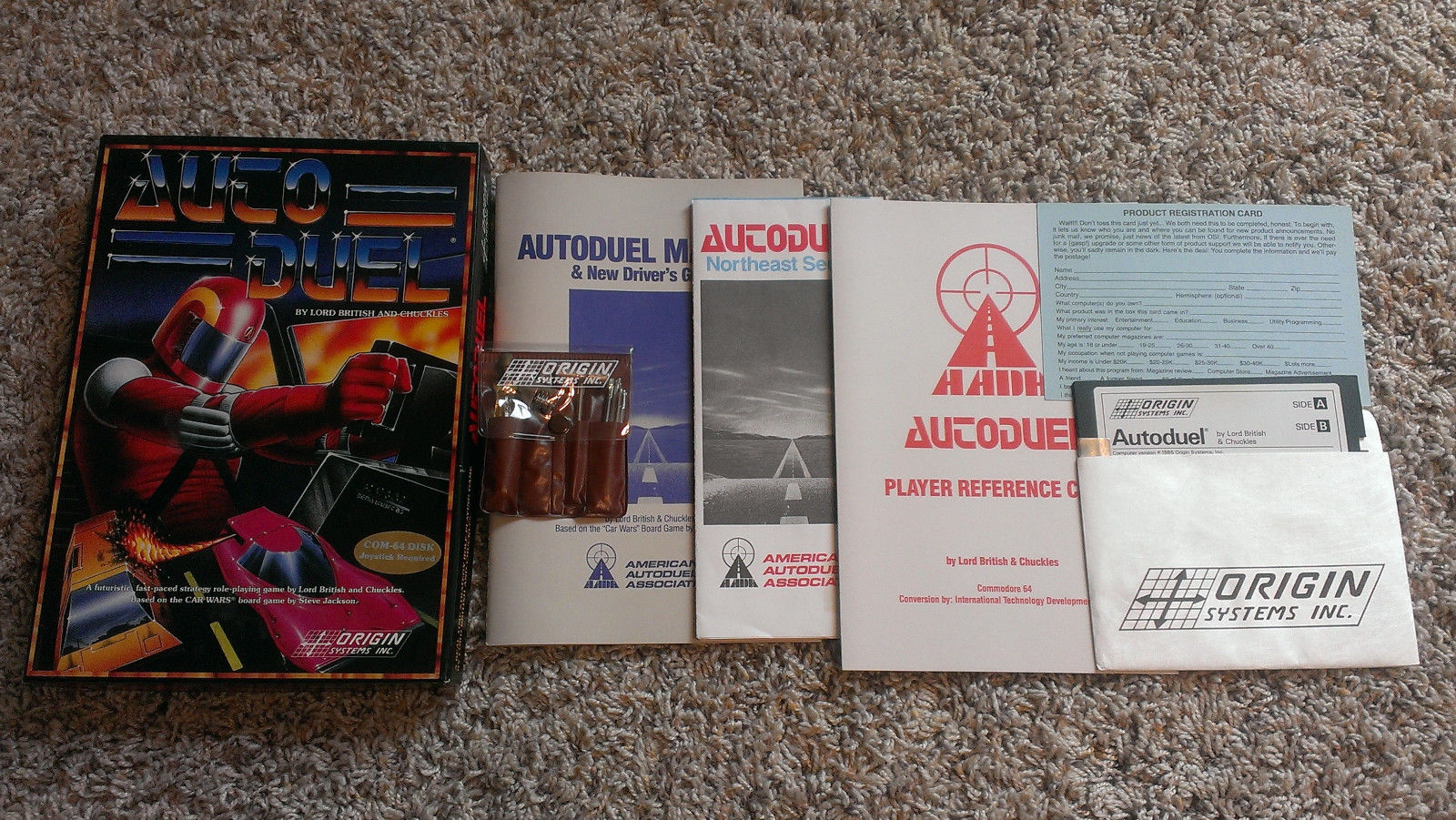

Autoduel

Image via eBay

The tool kit that came with Autoduel, the car combat sim based on Steve Jackson Games' Mad Max-esque RPG, is equal parts perfect, and perfectly useless, which is probably why I like it so much. It's an actual set of tools—a hammer, wrench, and multi-head screwdriver—but all miniaturized and stuffed inside an Origin Systems-branded pouch. There was no corresponding teeny little car to work on, sadly, so aside from maybe tightening up your glasses now and then, they were pretty much useless. But hey, it's not like that $180 statue of Alduin you've got sitting on your shelf is seeing a lot of day-to-day use, right?

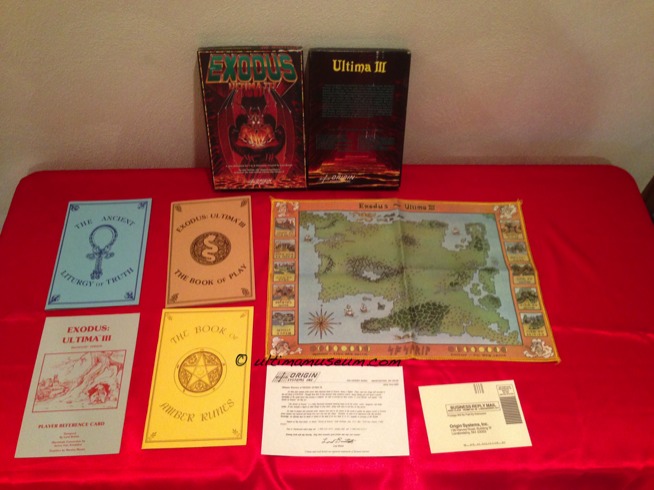

Ultima everything

Image via Ultima Museum

Ultima Underworld got a separate mention because it stands apart from the rest of the series (aside from Underworld 2, obviously), and also because any time an opportunity comes up to talk about it, I'm all in. But the rest of the Ultima series deserves notice, too. The first Ultima was relatively lightweight, containing just a brief instruction manual, but the loot wheels started turning with Ultima II: Revenge of the Enchantress, which packed in the Second Age of Darkness book, a cloth map of the Earth, and a "Galactic map," because that's how Ultima rolled back then. (Remember when the Avatar went to Mars?) That started a tradition of boxed-in maps and lore that persisted all the way through Ultima IX Ascension, the final game in the series, which included a map, eight Cards of Virtue, and a pair of softcover books, a Journal and a Spellbook.

Honorable mention: Preorder bonuses

Preorder a game these days and, if you're lucky, you'll get access to a beta for another game you might be interested in, or maybe a unique weapon or multiplayer skin as a "bonus." But things were different when I was your age.

Deus Ex: Invisible War may not have been a great game, but I got a free t-shirt for preordering—in its own box! Doom 3 wasn't a particularly good FPS, but preordering that one scored me a pewter pinkie demon figurine—in its own box!

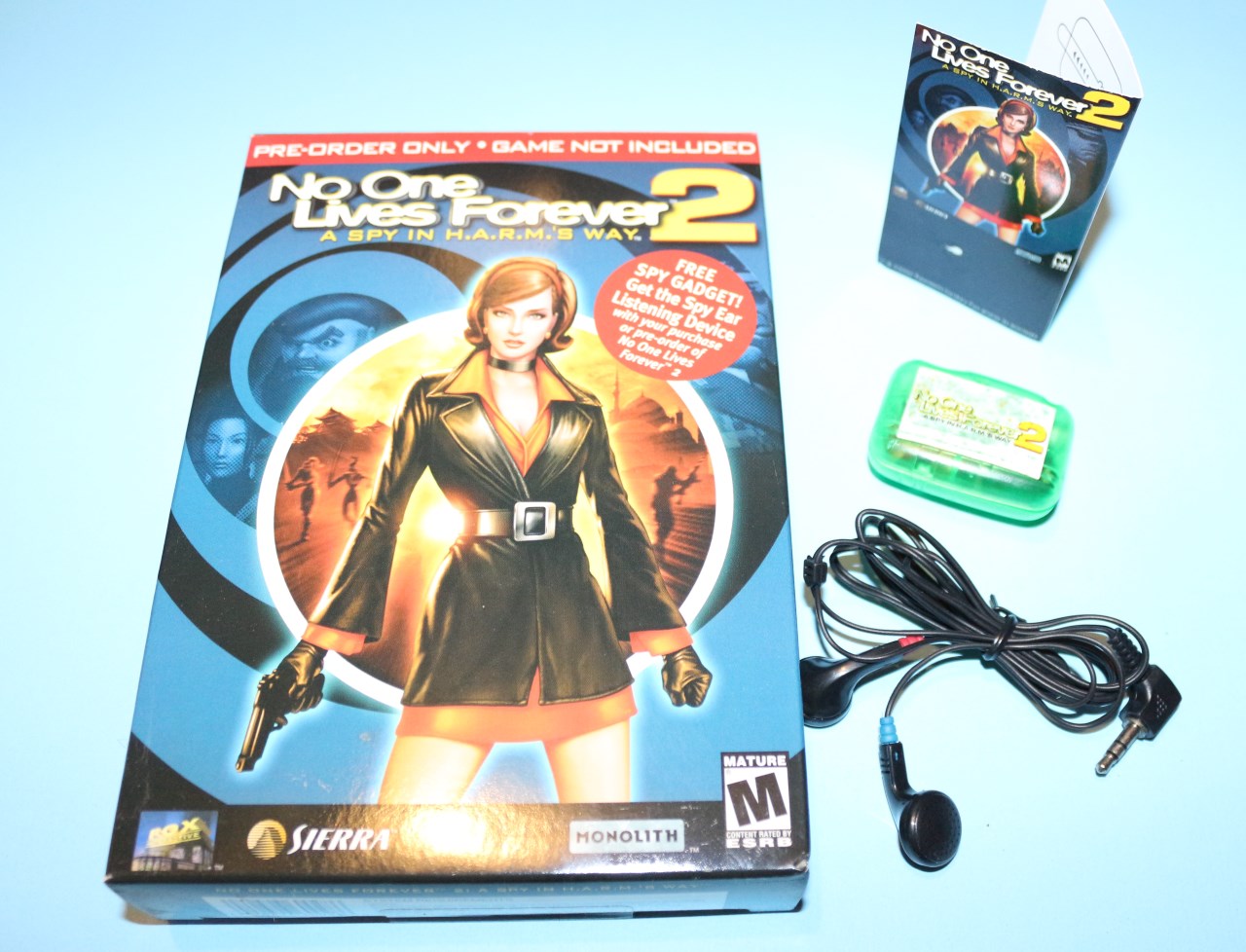

No One Lives Forever 2, well, it was actually quite good, and so was the preorder bonus: a "Spy Ear Listening Device," which was basically a NOLF 2-branded version of those cheap hearing amplifiers that used to get pimped a lot on late-night television. It actually worked, although not particularly well, but more importantly it was a gloriously ridiculous piece of nonsense that struck the ideal balance of "this is stupid" and "this is awesome" that marks the best of videogame feelies. And yes, it came in its own box.

Honorable mention: The box!

Look, this is all about the box, and so it's only fair that the boxes themselves get a little attention, right? The anonymous piece-of-crap DVD cases that game discs come in these days barely qualify for the term, and the standardized small-box containers that preceded them weren't much better. But back when the competition for attention was fought on store shelves rather than the front page of Steam, publishers did some crazy things to make their games stand out.

The first two Thief games came in trapezoid boxes. Dragon Dice had a clear plastic bubble containing a large die protruding from the front cover. The Infocom adventure Suspended was packed in a huge box with a cut-out front, exposing a nearly life-sized human face imprinted into plastic and made doubly-creepy by recessed eyes that follow you everywhere.

But as great (and awful) as that one is, my personal pick of packaging is Ultrabots, a 1993 giant fighting robots game from Electronic Arts that came in an articulated, telescopic box meant (I'm assuming) to simulate walking 'Bot legs. The game disc was contained in one leg, while the manual was in the other. It's flimsy, it's silly, the cost to produce them must have been astronomical, and aside from inspiring the occasional oldster flashback to the era of nutso game boxes, it serves no purpose whatsoever. I love it.

Andy has been gaming on PCs from the very beginning, starting as a youngster with text adventures and primitive action games on a cassette-based TRS80. From there he graduated to the glory days of Sierra Online adventures and Microprose sims, ran a local BBS, learned how to build PCs, and developed a longstanding love of RPGs, immersive sims, and shooters. He began writing videogame news in 2007 for The Escapist and somehow managed to avoid getting fired until 2014, when he joined the storied ranks of PC Gamer. He covers all aspects of the industry, from new game announcements and patch notes to legal disputes, Twitch beefs, esports, and Henry Cavill. Lots of Henry Cavill.

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Every Friday

GamesRadar+

Your weekly update on everything you could ever want to know about the games you already love, games we know you're going to love in the near future, and tales from the communities that surround them.

Every Thursday

GTA 6 O'clock

Our special GTA 6 newsletter, with breaking news, insider info, and rumor analysis from the award-winning GTA 6 O'clock experts.

Every Friday

Knowledge

From the creators of Edge: A weekly videogame industry newsletter with analysis from expert writers, guidance from professionals, and insight into what's on the horizon.

Every Thursday

The Setup

Hardware nerds unite, sign up to our free tech newsletter for a weekly digest of the hottest new tech, the latest gadgets on the test bench, and much more.

Every Wednesday

Switch 2 Spotlight

Sign up to our new Switch 2 newsletter, where we bring you the latest talking points on Nintendo's new console each week, bring you up to date on the news, and recommend what games to play.

Every Saturday

The Watchlist

Subscribe for a weekly digest of the movie and TV news that matters, direct to your inbox. From first-look trailers, interviews, reviews and explainers, we've got you covered.

Once a month

SFX

Get sneak previews, exclusive competitions and details of special events each month!