Black Dogs And Broken Toys

Every week, Richard Cobbett talks about the world of story and writing in games.

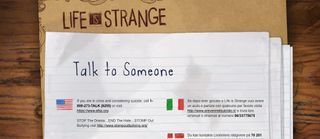

While I won't spoil what leads up to it, the latest episode of the adventure game Life Is Strange features something I don't believe I've seen in a game before - contact information for a suicide hotline. It's an inclusion that I'm sure some people out there are mocking right now, but one I entirely applaud. Mental health issues are often shrugged off as simply being whiny, attention-seeking, self-indulgent or no big deal, and all of that is, pardon my French, complete bollocks. Depression, anxiety, isolation and despair are very real problems, and they kill. They kill a heck of a lot of people, in no small part thanks to false perceptions that they're something that can simply be walked off, that 'go make some friends' is a helpful suggestion, and a worryingly persistent view that mental health issues are nothing but the fucking gom jabbar from Dune; an illusory pain to 'beat'.

(Yes, I am aware that the gom jabbar is the needle, not the box. Sssh.)

Again, I won't go into the plot details behind why Life is Strange felt the need to display what it did, but it's worth addressing a very important reason why such things are entirely worth doing - not that players are likely to jump out of a window while the credits are rolling, not that the moment is so emotive that they'll need to speak to someone... though if either of those facts are true, I of course hope that it helps. Instead, its benefit and all the justification needed for its inclusion is to push the single most important, most life-saving message in mental health: You are not alone.

What's often interesting about how people connect to this message is that it doesn't necessarily matter how the specific situation resolves itself or whether it's wrapped in a fictional context; the sense that connection is even possible can be meaningful. Pondering this column, something I quickly noticed was that very few game characters I can think of who suffer from depression and related issues actually solve it, and that in most cases them doing so wouldn't ring true - as tends to be the case in reality, it tends to be embedded deeper down than that. Even something as bluntly written as Squall's monologue in Final Fantasy VIII has profound layers to it, from his painful awareness of his own irrationality, to his fear, to its root in self-hatred. These are not personal issues that can be solved by beating up a half-naked witch.

Generally though, narrative is best when it uses the old rule 'show don't tell'. Zoe Castillo from Dreamfall is a pretty good example there. On the surface, she seems to have it all - smart, talented, sexy, well off family, has friends, cracks jokes... but much like real world depression, none of it matters. The spectre of the black dog hangs over her from her earliest conversations, sapping her resolve, turning the world grey.

Now, as is often the case, when destiny calls she is indeed fired up and ready to be a heroine, finding meaning in saving the universe. Like her Longest Journey predecessor April Ryan though, that's only part of the story, and she also has to deal with what happens when the quest ends and there is no more destiny to have (at least until the sequel finally showed up, but we'll get to that.) Her reward for saving the world is... to simply end up back where she started, once again just walking the streets of Casablanca with no plan, no purpose, while this melancholy tune plays in wistful reference to everything and nothing.

Did you hear me whispering hello?

The biggest gaming news, reviews and hardware deals

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

Did you see me waving goodbye?

Did you notice... that I didn't cry?

Not exactly a heroine's return, even ignoring the cliffhanger. Despite that though, it feels right... and it feels right because anyone who can identify with Zoe in the first place also knows that distraction isn't necessarily a fix, and that not even being able to save the world guarantees being able to vanquish the black dog.

Needless to say, Dreamfall Chapters picks up on this when we finally return to her, in therapy and on the surface, doing much better. It very quickly becomes clear that she hasn't been magically cured though, with her journal showing her desperation to so much as find a proper friend, her attempts to get involved with politics more about convincing herself that she's helping than any heartfelt belief in her chosen candidate, and her relationship with her boyfriend Reza an extremely awkward romance that she seems to be like she's clutching to because... well... that's the kind of thing people do if they want to to be happy, right? Right? It remains to be seen how the series continues, especially given A Certain Thing in the second episode, but it's already a continuation of the series' excellent exploration of these problems.

Adventures are generally very very well suited to explore this territory, though of course that's not to rule out other genres. I can already hear people shouting about the good Silent Hill games for instance, and can think of moments in quite a few others myself - the mental breakdown of Lt. Marta Velasquez for instance, star pilot and scourge of Traffic Department 2192, or the showy but still effective Spec Ops: The Line. (What I can't think of are any good examples of where it's been done as something like a 2D platform game, no matter how many of them are splattered over Newgrounds and related sites. But hey, keep trying!) One very effective one I'd highlight is Cart Life, which features narrative, but primarily grinds in the mood through its mechanics and moments of empathy both for your character directly and others in equally bad situations. (Papers Please too, though less so due to its focus. Also This War Of Mine, of course, where failure isn't the only option, but it often feels like it.)

Despite this, it's really been since the launch of Twine that we've seen a surge in games exploring this kind of subject, and I doubt there'd be much argument that a big reason is the catharsis factor - people suddenly having the tools to express themselves, along with the shielding element of being able to step aside, present it as a story, be able to have characters express what might otherwise be impossible. This is not even remotely intended as a criticism. What is horror if not an exploration of what scares us? What is fantasy if not on at least some level wish-fulfilment? Fiction has power.

Of the Twine games, Depression Quest is of course the most infamous, but if it's a bit on-the-nose for you, try Richard Goodness' Zest - an acidic game about the days just grinding past, day after day after day, broken only by occasional bursts of frustration, drugs and futility. Other indie authors of course have used other tools, creating the likes of The Cat Lady with Adventure Game Studio - a game whose pitch begins "The Cat Lady follows Susan Ashworth, a lonely 40-year old on the verge of suicide. She has no family, no friends and no hope for a better future," and then promises things aren't going to get much cheerier. Another technical step up, you'll find games like the collaborative project Serena, which wraps everything in a mystery, and Gone Home, in which the depression aspect is witnessed rather than felt by the lead character.

Easily the best portrayal of depression, isolation and anxiety that I've seen in an indie game though is in Wadjet Eye's Blackwell series. Much like Dreamfall, it's a lingering presence that rarely becomes particularly overt, but written with a generally more optimistic touch. It's the story of Rosa Blackwell and her ghost partner Joey Mallone, as she helps lost souls find their way to the next world from the streets of New York, and a little like Zoe Castillo, she starts the series in a bit of a state. She has no friends, she's so isolated that she can't even talk to her neighbour in the park, and work isn't exactly going to plan. On the one hand, her destiny absolutely ruins her life. She's seen as crazy, a suspect rather than a saviour, the relatives of the people she helps are more likely to send her a restraining order than a thank you card, and she literally can't get more than a few feet away from Joey due to their spiritual link.

I said optimistic, right? I'm getting there. Because the second game, Blackwell Unbound, is a side-story about Rosa's aunt Lauren. Lauren is a wonderful creation, and quickly became a fan-favourite character, but her primary role in the story is to be Rosa's mirror. Unlike Rosa, we meet her as an experienced medium, and one whose snark and greater assertiveness can't hide the fact that the job is crushing her. Whatever she might have cared once, it's gone. "Life. Death. Tormented souls. It's all the same to me," she muses, using the series' gateway to infinity as nothing but a quiet place to take an illicit smoke break and a few seconds peace and quiet.

Although Lauren only stars in one game (and appears in one other), she proves very important to contrast Rosa's development. Rosa doesn't have an easy time of it... ever, really.. but over the series we see the slow but steady defeat of her black dog as she comes out of her shell, becomes more assertive, and ultimately takes control of destiny instead of simply being dragged along by the hair. What marks the Blackwell series though is how well, and how believably this is handled over the series. There's no bit where Rosa has a moment of self-realisation and actively decides to change things, or even particularly notices. Nor does it simply happen with the wave of a magic wand. Instead, it's shown through both spoken and unspoken dialogue, details and little moments, that the key difference between the two women is that Rosa is able to turn her attention outwards, to show compassion and embrace her duty as a calling. Lauren instead turned inwards, building walls and hiding away to the point of being incredulous when another character tries to tell her "You are loved."

The game doesn't need to add that it's by Joey, any more than he'd ever tell. Nor does it blame her for any of this, being both smart and compassionate enough to accept that it might be her curse (and it doesn't get much better), but it's not her fault.

All of these games take very different approaches to these issues, with different degrees of fantasy, alternate outlooks, and philosophies that range from hopeful to bittersweet to downright depressing. It's not necessarily that that defines how they land though, with some happy endings ending as sad as a summer's day without friends, whether by seeming impossible or dangling the possibility on an unreachable chain, and some seemingly tragic ones blooming like beautiful wildflowers.

As stories get deeper, and the instruments of narrative grow more subtle, it's things like this that will allow for both deeper characters and more emotionally affecting stories - not simply depression, but a whole spectrum of joys and sorrows that turn polygons into people we can feel sorry for, think of friends, and maybe through VR, finally reach out and give the hug that they need. As much as people write off diversity as simply political correctness, it's always been about more than that. Games, more than any other medium, can build direct emotional connections through words and actions and choices made, and the wider the palette, the more exciting the possibilities. For those lucky enough not to be affected, that's important. For those who are, and especially those who are isolated for whatever reason, it could be a life-saver. It may seem like a small gesture, a pointless gesture, even a silly gesture, but it's not. Sometimes, for whatever reason, everyone just needs to be told "you are not alone."

We are not alone.

Overwatch 2 achieves the improbable, clawing back a 'Mixed' rating in recent Steam reviews after a well-received perks update

'A wizard is never late, nor is he early, he arrives precisely when he means to,' but it's a different story for hobbits because Tales of the Shire is delayed again

Most Popular