Are qualifiers like "alpha" and "beta" used too liberally to justify selling unfinished products, or are monetized testing phases beneficial to PC gaming? In this Face Off debate, Tyler goes pro on the latter: sell what you want, he says, because it's the player's job to make informed buying decisions. T.J.'s on Con Air, and says that if players can buy the game it should be called what it is: released.

Jump over to the next page for more opinions from the PC Gamer community, and make your own arguments in the comments. Debate team captains: it's your time to shine.

Tyler: Go ahead, say it .

T.J.: *cough* The War Z. Sorry, what?

Tyler: I thought so. Alright, yes, there was some shady wording in its Steam description , but that was a unique case. In general, it's fine for devs to charge for unfinished games as long as they're upfront about it. If you don't want to troubleshoot or put up with missing features, then don't be an early adopter.

T.J.: No, you're right. The War Z, while it would help my case, is a one-off thing. It's a prime example of how bad this phenomenon can get, but it's not emblematic of the larger issue. There are two states a game can be in: Purchasable and Not Purchasable. If I'm paying for the game, and you're telling me it's “not out yet” or a “Foundation Release,” you're blatantly using wordplay to cover up what you seem to see as a blemish on your own product.

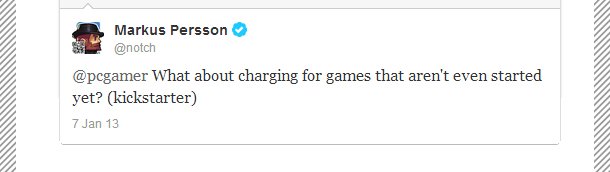

Tyler: Wordplay shmordplay! We all know betas are works-in-progress, and anyway, they're important . For indie devs, pre-release adopters can furnish the funds and feedback they need to keep developing. That's a beautiful thing—community and developer working hand-in-hand—and it sure as hell worked for Minecraft. If Notch had tried to “finish” Minecraft before release, where would we be today? In a world devoid of cubes, that's where.

The biggest gaming news, reviews and hardware deals

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

T.J.: I conceded that The War Z is a one-off thing, and now you throw out Minecraft like that's the norm?

Tyler: Touché, Hafer.

T.J.: Which was, interestingly enough, one of my nicknames in high school. But anyway, indie devs, if they want to be taken seriously, can't expect gamers to hold them to a different standard in this department than the big guys. Yeah, Minecraft was called an “alpha” when it first went up for purchase. But it was also a pretty full-featured game without too many fun-ruining bugs that you could happily spend a lot of time in. I don't feel like it needed to be labeled an alpha. So just drop the excuses and call it “Minecraft.” And it's not just indie devs that are guilty of this name game, either.

Tyler: Right, and buggy games suck, but it doesn't make a difference if it's an alpha, beta, gamma, or whatever. The beta tag actually helps us with buyer's risk, because it ought to tell consumers: “This isn't done yet, so you'd better ask around before committing.” It's actually more honest to call your buggy, unpolished game a beta than it is to call it finished.

T.J.: No, it's more honest not to charge money until you're comfortable doing so without a qualifying label. Almost everything is a “work in progress” these days, anyway. People expect that. Games like League of Legends have added massive amounts of post-launch content, even without boxed expansions. If you want people to test your game that you feel is underpolished and not ready for prime time, give it to them for free.

Tyler: Again, betas are part of the business model for a lot of these games. Development takes a long time and a lot of money, so earning revenue during the testing phase just makes sense. The super-fans get to jump in early, and the dev gets financial breathing room while it analyzes feedback. It's win-win.

T.J.: I'm not asking them to give up their business model, but the line at which a dev feels justified charging money should be near or overlapping the line at which they no longer feel the need to use the “beta” or “pre-release” labels. Sell the game, as a full game, with the features you have done, and talk about your plans for future content. If you really don't have the resources you need to put out what you're comfortable labeling a finished game, run a Kickstarter.

Tyler: How is Kickstarter better? It's just a market for promises. There's no guarantee you'll get anything, even an unfinished version of the game, so it achieves the same thing but with no instant gratification. That is, unless the dev is giving out a beta version as a contribution award, like FTL did, in which case... you're buying a beta! When you drop the crowdfunding buzzwords, there's no difference.

T.J.: The difference, I guess, lies in whether you actually have the funds to make the game without having to resort to fundraising (and thus, using beta access as an incentive). There's a difference between saying, "We couldn't make this game without your help, and we're going to let you play an early version as a reward for helping foot the bill," and "Here, we want you to pay us for this before it's met our own standards for release." One brings us games that couldn't happen otherwise, while the other comes across as sleight of hand.

Tyler: Leave David Copperfield out of this. He's a national treasure.

For more thoughts on PC gaming, follow Tyler , T.J. , and PC Gamer on Twitter. On the next page: more opinions from the community.

PC Gamer is the global authority on PC games—starting in 1993 with the magazine, and then in 2010 with this website you're currently reading. We have writers across the US, Canada, UK and Australia, who you can read about here.