Our Verdict

Capy’s tough-love approach and well-worn survival systems makes it harder to appreciate Below’s singular look and feel.

PC Gamer's got your back

What is it? A challenging crawl through a procedurally-generated labyrinth.

Expect to pay £18/$22.50

Developer Capybara Games

Publisher In-house

Reviewed on Intel Core i5-8350K CPU, 8GB RAM, GeForce GTX 1060

Multiplayer? No

Link Official site

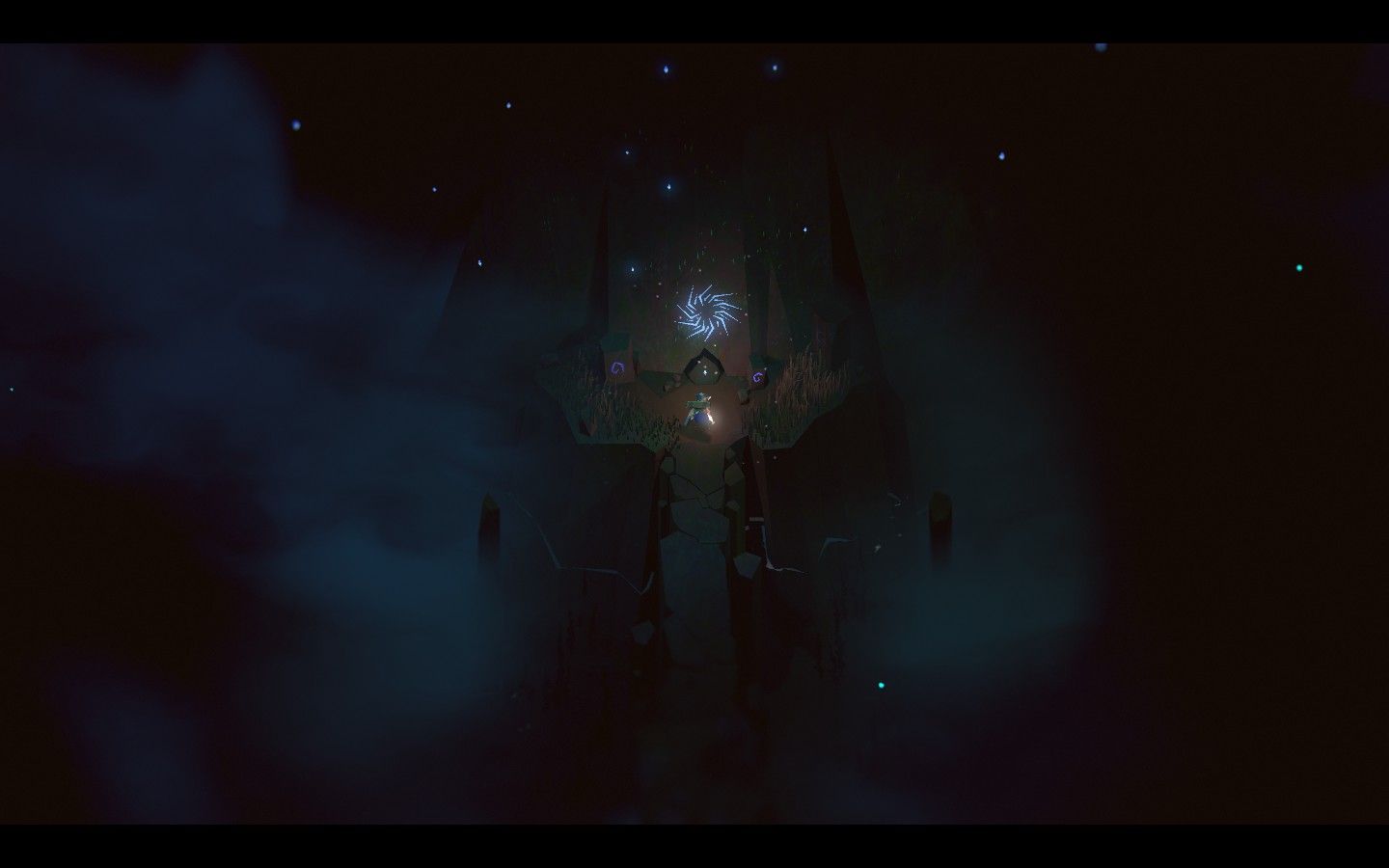

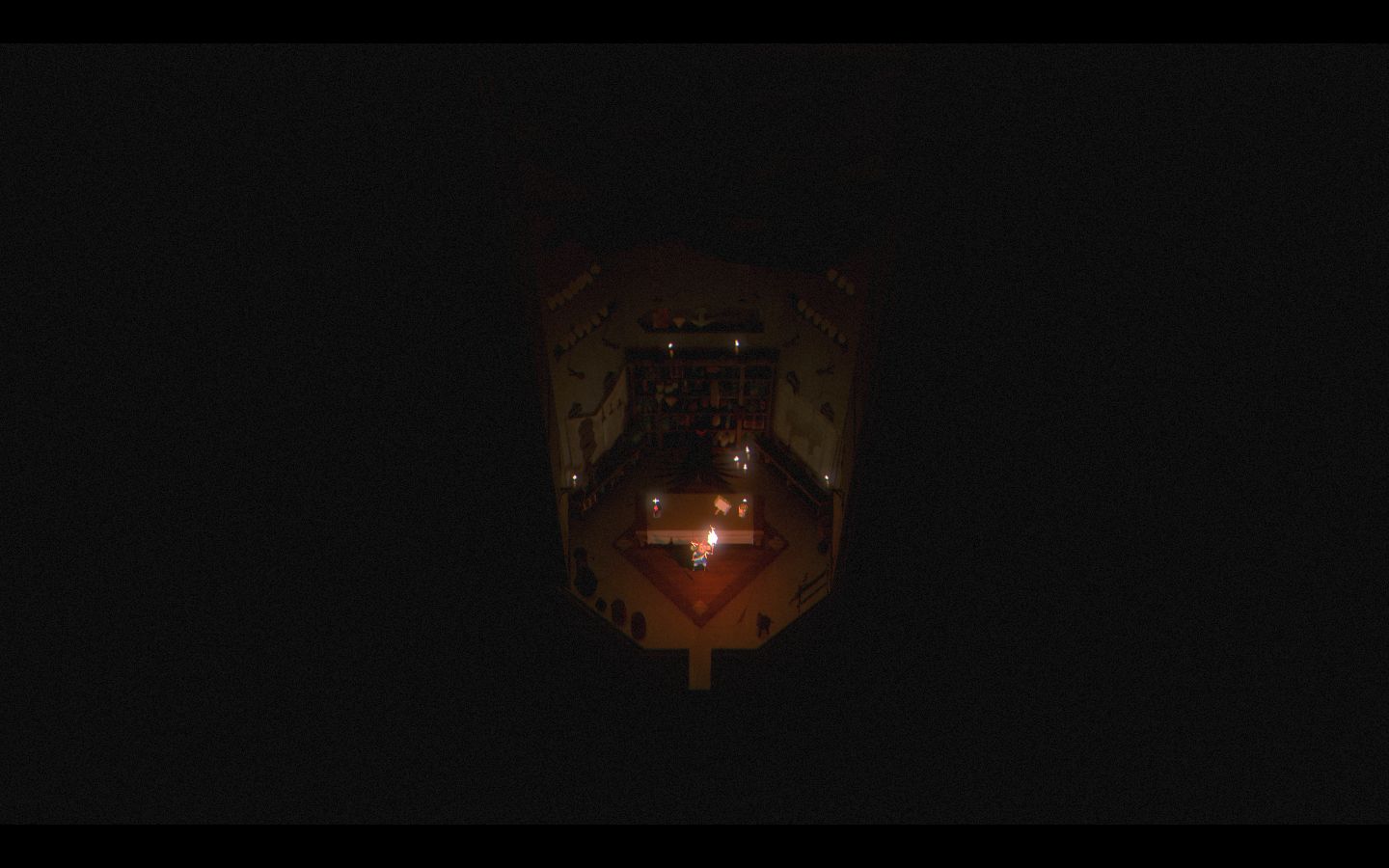

Like a reverse-world version of Hideo Kojima’s solar-powered dungeon-crawler Boktai, Capy’s uncompromising roguelite demands to be played in total darkness. It’s made to be experienced on PC, ideally hunched over in front of a monitor in the wee small hours. Here, you’ll find yourself instinctively leaning in to better make out your minuscule character and their surroundings. It may not do much for your posture—or your eyesight, for that matter—but you’ll feel a physical connection to your brave adventurer, likewise peering anxiously into the gloom.

An indulgently slow opening sees the camera descend at a snail’s pace towards a tiny speck that becomes a sailboat, tossed around by a roiling sea. Eventually, it lands on a beach from where you begin a long climb to the labyrinth you’re here to explore. There’s a whiff of self-importance about the whole routine, but this is Below’s way of letting you know that you need to be patient. Taking your time pays off—up to a point.

In its early hours, Below is heady, powerful stuff. Its tilt-shift aesthetic works minor wonders with scale, leaving you feeling particularly small and vulnerable. Its gloomy environments are shrouded in a mist that only clears as you inch forward, sword and shield at the ready for the creatures that scuttle forth, their red crystals glinting from the murk as an ominous early warning. As your every action echoes eerily around the rocks, Jim Guthrie’s shivery, menacing score, deployed with careful economy, steels you for the perils to come.

It’s economical in other ways, too. Below gives almost nothing away; gratifyingly, you learn only by doing. And though a few lessons are learned the hard way—and others are decidedly unintuitive—it’s generally a pretty good teacher. Take the crystals dropped by the creatures you encounter early on: these power your lantern, which naturally illuminates your environment, but also activates mechanisms and reveals secrets. But the gems have a habit of bouncing off ledges if you swing your sword wildly at anything that approaches. As such, you’re best off using single, precise swipes, or jabbing from behind your shield. Not that you can afford to be too picky about tactics when they swarm you from all sides.

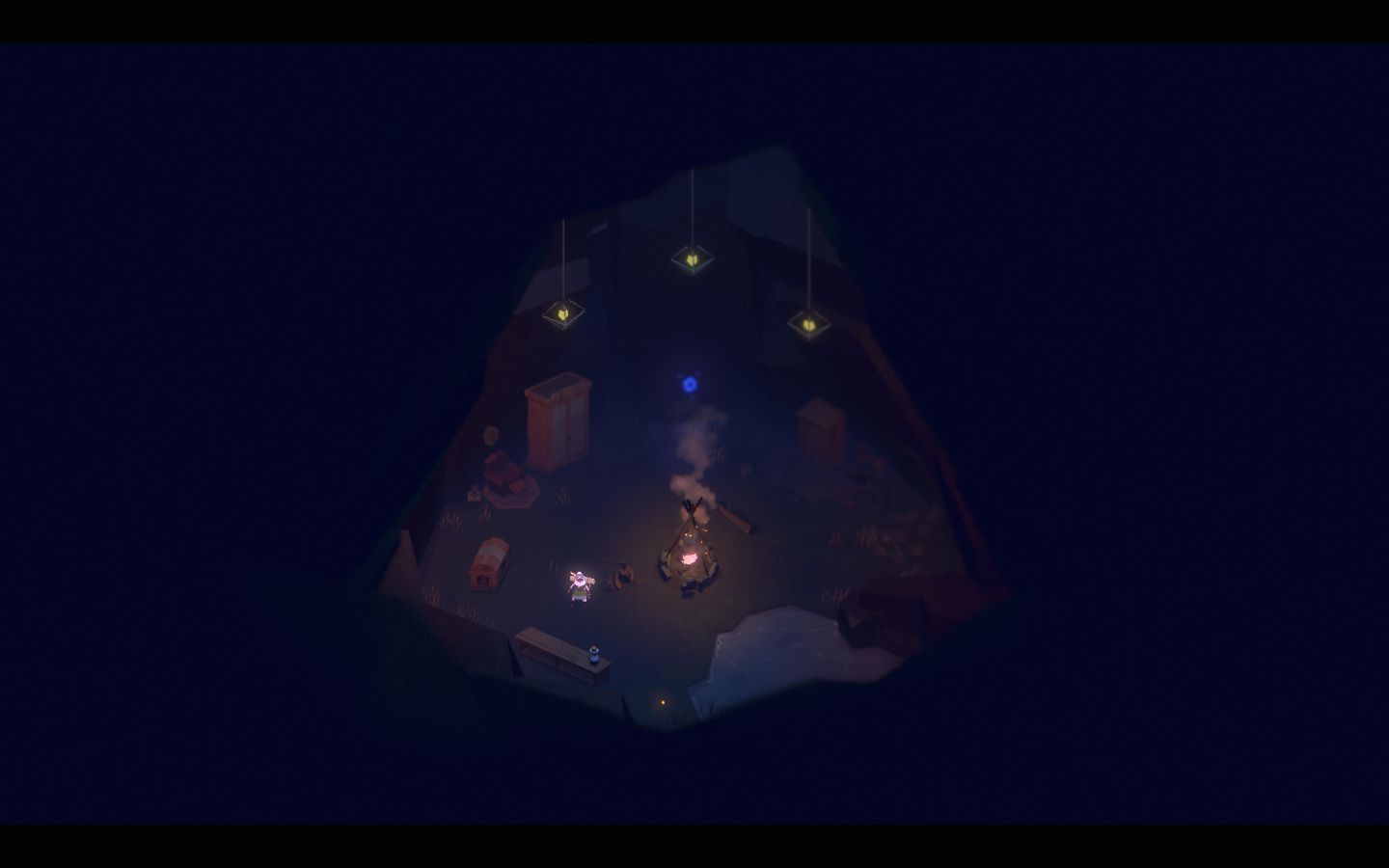

If you are hit, you’ll usually start bleeding. You can either apply a bandage you’ve found or crafted, or cauterise the wound at a nearby brazier. Lighting it takes a few fraught seconds, however—unless you’ve a torch in hand—and enemies will mercilessly target you when they know you’re occupied. It’s this tension that means surviving several rooms’ worth of red lights unscathed leaves you feeling thrillingly alive, and spotting a campfire to rest at brings a warming feeling of relief. Here you can sleep and visit a dreamlike hub where you can leave items for your successor—albeit at the cost of leaving yourself short for the immediate journey ahead. Though doing so will free up space in your limited inventory, perhaps for more valuable items.

This kind of calculated risk is part of what makes Below initially so absorbing, but the game’s ruthlessness too often tilts over into outright unfairness. Insta-kill spike traps are a devious trick you won’t fall for often, but occasionally they’re placed behind scenery with barely a couple of pixels in plain view. Enemies can sometimes hit through walls, while in a game where split-second timing is crucial, the odd sluggish input can mean the difference between successfully stemming a potentially fatal wound and losing 20 minutes of progress.

From crafting to combat to campfire checkpoints, Below feels a little behind the times

Finding shortcuts soothes some of the frustration, but that only goes so far. Reaching your corpse lets you retrieve its inventory, but as gaps between campfires grow ever wider, and your ability to create checkpoints gets steadily more challenging, you’re forced to go on suicide runs, purely to stock up on supplies to leave at the hub. Food and water, more readily available higher up, is particularly essential, since hunger and thirst eats away at your health if you don’t fill your stomach. And at one stage you’re suddenly forced to think about body temperature, too.

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

It’s too much. These survival elements discourage the desire to properly explore, since you haven’t really got the time. The combat, too, suggests a precise methodical approach you can ill afford, since you’re constantly against the clock. And the procedural elements that subtly change floor layouts are both too much and not enough: you can’t memorise and thus master your domain, but the trek back to your body rarely yields any fresh and exciting discoveries. The occasional shock of the new feels like scant reward for the significant effort invested in getting there.

Even after all this time, Below doesn’t quite seem to be ready. More damagingly, it feels like it’s been surpassed in places. During its long journey to the light, the survival genre has flourished. Few of its peers can match it for atmosphere, but from crafting to combat to campfire checkpoints, Below feels a little behind the times.

Capy’s tough-love approach and well-worn survival systems makes it harder to appreciate Below’s singular look and feel.