Battletech is shaping up to be a great tactical combat game, and an absorbing mercenary sim

Harebrained's latest channels the spirit of tabletop mech adventure.

Dekker has fallen over. His 30-metre-tall mech is prone at a desert crossroads, flanked on two sides by canyon walls that do not—it turns out—prevent him from being shelled by artillery. I’d sent him in because his mech is the most armoured: his job was to tie up enemy firepower while my quicker mechs flanked through a lowland forest to the south.

I’m commanding a lance—a squad of four mechs—featuring designs and loadouts that’ll be familiar if you’ve ever played a MechWarrior game. BattleTech pulls the series back to its tabletop roots, focusing on strategic combat between mercenary outfits who dip in and out of star-spanning future wars to turn a profit. In this specific instance, I’ve been tasked with blowing up valuable buildings in two separate locations. As Dekker and another heavy mech approach the gates head-on, I’ve set up a flanking strike to eliminate the power generator sustaining the base’s turrets. At least, that’s the plan.

A bit of faulty reconnaissance on my part means that I didn’t realise that the enemy base defences don’t need line of sight to open up on my heaviest mech. Similarly, while years of MechWarrior games have left me wise to the dangers of overheating, I didn’t consider stability. Dekker’s armour repels the worst of the missiles that rain down on him from the far side of the hill, but their explosive impact is enough to send him off balance and, ultimately, crashing down to the floor.

It’ll take a two-part plan to save him. In the forest to the south, my two flanking mechs really need to take out that power generator. And Dekker’s wingmate—no small mech herself—needs to take out the enemy mech that is acting as a spotter for that distant artillery. Neither of these things go quite to plan.

Although you have a degree of real-time control over your mechs as they explore the battlefield, contact with an enemy causes the game to shift into a turn-based system based on each pilot’s initiative. In each phase of the fight you can choose a mech to activate and perform a move action followed by an attack. It’s a little like XCOM, but much more granular in a way that feels like a tabletop game. I choose one of my flanking mechs and instruct her to use her jump jets to reach a higher vantage point, risking her heat sinks in order to take the shot that might save Dekker. She opens up her medium lasers on the entirely stationary, very large generator—and misses.

Dekker takes another round of fire and loses his mech’s left arm. He stands and opens fire with all of his remaining weaponry, tearing chunks out of the enemy walker but overheating in the process.

Dekker takes another round of fire and loses his mech’s left arm. He stands and opens fire with all of his remaining weaponry, tearing chunks out of the enemy walker but overheating in the process. The next round of artillery fire incapacitates him—he has a chance to crawl away from the wreckage alive, but I won’t find out until the end of the mission (had I chosen to eject him rather than attack, I could’ve ensured his survival).

In response, Dekker’s wingmate charges the enemy mech and performs a melee attack—a first for a BattleTech game. Mechs don’t have melee weapons, and there’s nothing elegant about ramming them into each other—this is a sprinting shoulder-charge that smashes catastrophically into the enemy. I get lucky—the enemy pilot is killed, and their mech collapses. The artillery opens up again, but it won’t get to fire after that. I move another mech into a flanking position, and this time they can hit the broad side of a power generator.

The biggest gaming news, reviews and hardware deals

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

There’s loads to like about BattleTech as a purely tactical game: you’ve got a lot of control over your squad’s positioning and weapon options, and achieving an advantageous position means carefully paying attention to altitude, heat and, yes, stability. This single combat encounter is a straightforward example of the drama that the game generates on the fly. Later on, I discover the thrill of using jump jets to deliver fatal drop attacks on tanks like an expensive metal Mario, and conduct the rest of the mission in this manner.

It’s the broader strategic layer that has me excited for BattleTech, however. The events of this mission are shaped by—and shape—a much bigger and more open-ended attempt to earn a dime as a mech-commanding space mercenary. For example: while Dekker-the-pilot was unable to escape the burning wreck of his mech, the mech itself was not completely unsalvageable. Yet the specific damage it took will need repairing, and if there were any expensive guns bolted to that left arm—well, it’s gone. That’s a potentially expensive loss that’ll need accounting for when I decide to take on my next mission. Also, you know, Dekker’s dead, and that’ll probably have an impact on morale.

Each of your pilots has a randomly-generated personal history, which influences their outlook and connections.

Back on the ship (initially a small Leopard-class dropship, later a massive upgradable hulk called the Argo) there are loads of decisions to make. Each of your pilots has a randomly-generated personal history, which influences their outlook and connections. You’ve got your own baggage too—you create your main character through a questionnaire at the beginning of the game that reminds me a little of the Mount & Blade series.

These factors influence the types of missions that will be made available to you beyond the confines of the story-led critical path. When you take on a mission, you can choose to emphasise payment, salvage rights, or forego either to make factions like you more. Salvage rights are deliciously specific, too—what you get depends on the outcome of the battle that is subsequently fought, so if you’ve chosen to take your payment in the form of scrap then you’d better be sure that you only blow the bits off enemy mechs that you don’t want to keep.

You might choose to take missions in tundras or wetlands where the environment can be used to keep your mechs cool and able to sustain their firepower for longer, or head to the desert with a more lightly-armed contingent that can exploit the temperature to their own advantage. You might try to curry favour with one of the great houses of the BattleTech universe, or slum it with pirates and steer clear of interplanetary war.

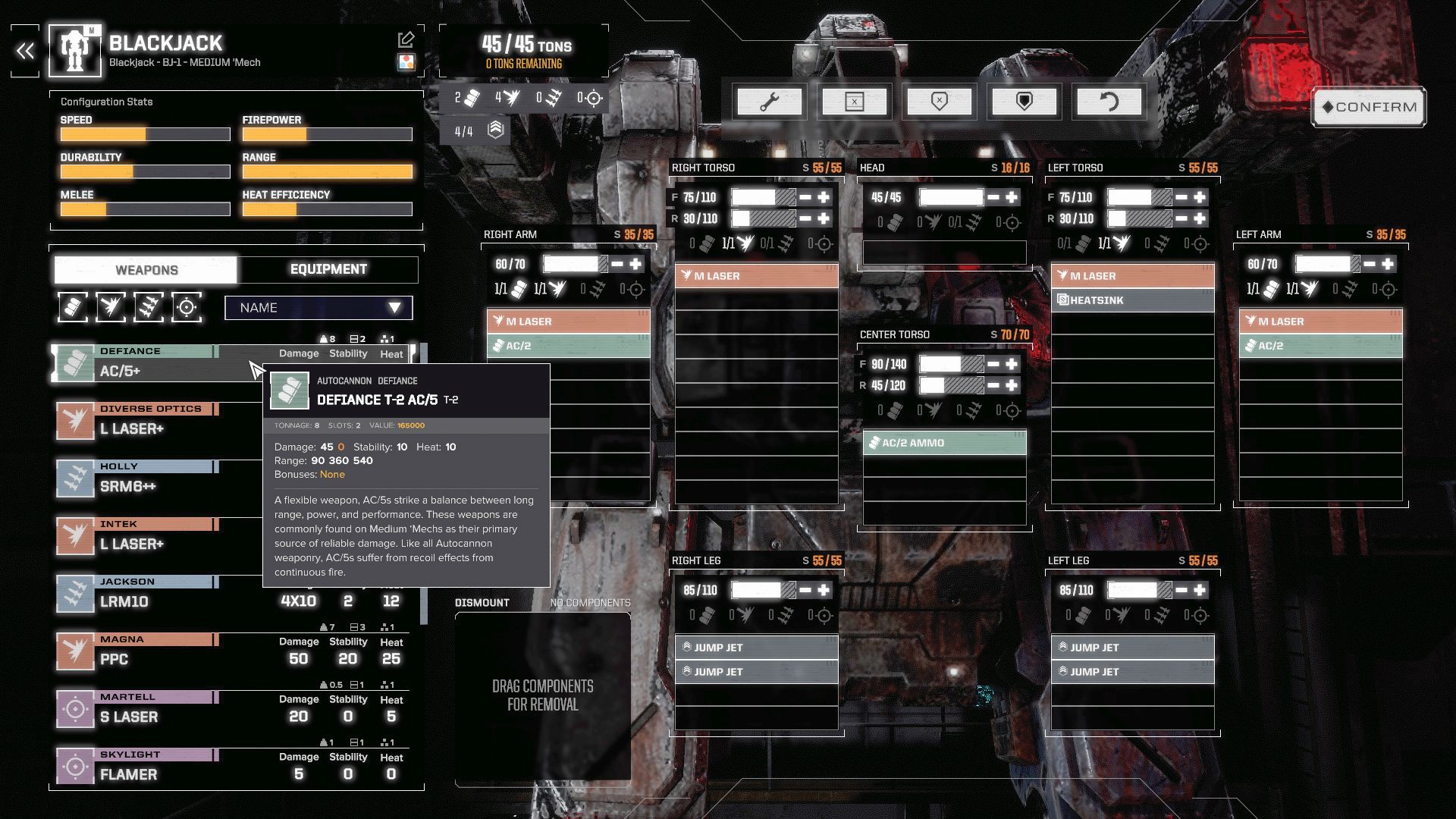

You’ve got loads of freedom to refit each mech to your specific needs, but these changes take up both money and time. A week-long refit will be broken down into subtasks, and if you choose to interrupt work to get a mech into the field in a hurry you may find that your engineers have finished fitting the new gun but not, say, loaded its ammo. As time passes you’ll occasionally be presented with shipboard events, mini choose-your-own-adventure digressions with consequences for morale. And morale, in turn, influences your pilots’ performance in battle.

There’s a lot of XCOM to this structure, but unlike XCOM the stakes in BattleTech aren’t quite as high. Certainly your employers would like you to succeed, but you’re not trying to save the world—you’re trying to make a living. Taking heroic risks (like, for example, wandering your biggest mech unsupported into the line of fire) isn’t always the right call. To reflect this, missions don’t have a straightforward success or failure state: if you choose to retreat from a mission with only half your objectives completed, that’s not necessarily an outright disaster. Depending on exactly what you managed to achieve, you may come away with partial payment and a slight knock to your reputation but—crucially—a ship full of pilots who are still alive and mechs that don’t need expensive repairs, which is its own form of success.

This feels like underexplored space for this type of game. I’m really taken with the idea of a campaign system that discourages save-scumming by giving you more freedom to make the best of a bad situation. And the detailed links between BattleTech’s galaxy-spanning ‘sim game’ and on-the-ground combat are something I’d like to see much more of—being a good space-war businessperson isn’t just a matter of making the right macro-scale decisions, but of optimising your efficiency on the battlefield, too. There’s loads of potential for interesting stories to come from these systems—and, yes, like XCOM, you can rename all of your pilots after your mates. And apologise to them in person when your bad decisions result in them falling over and exploding.

Joining in 2011, Chris made his start with PC Gamer turning beautiful trees into magazines, first as a writer and later as deputy editor. Once PCG's reluctant MMO champion , his discovery of Dota 2 in 2012 led him to much darker, stranger places. In 2015, Chris became the editor of PC Gamer Pro, overseeing our online coverage of competitive gaming and esports. He left in 2017, and can be now found making games and recording the Crate & Crowbar podcast.