The history of the strategy game

The origin and evolution of one of PC gaming's quintessential genres.

This article ran in two parts across PC Gamer issues 324 and 325. For more quality articles about all things PC gaming, you can subscribe now in the UK and the US.

The history of computer strategy games begins on tables and boards, crammed inside cupboards alongside that knackered old box of Risk that every home seems to possess. The moment strategy made the leap to consoles and computers, it was already familiar. These weren’t just inspired by the games people were playing, in many cases they were direct copies that had been squeezed, sometimes awkwardly, onto a new platform.

In 1972, Invasion was released for the Magnavox Odyssey. It was Risk, essentially, but with Pong-like battles that were fought on top of overlays that had to be slapped on the front of the television. Aside from the battles, Invasion was mostly played on a physical board, so the actual strategy game didn’t really take place on the console at all. The Odyssey’s limited capabilities ended at displaying a few squares that could be moved by twiddling the knobs attached to the little boxes that served as controllers.

The success of microcomputers like the TRS-80 and Apple II inspired a new wave of tabletop adaptations, spearheaded by Strategic Simulations Inc. So began a cavalcade of wargames, and more than a few RPGs, that would last for around 20 years. Founder Joe Billings had shopped around the idea of making adaptations of existing wargames to tabletop publishers like Avalon Hill, but had no takers. That didn’t deter him. SSI’s first game, Computer Bismarck, bore a striking resemblance to Avalon Hill’s Bismarck. The publisher noticed.

Quickly, Avalon Hill started releasing its own games on computers, competing with SSI. The pair churned out wargames with dizzying momentum, but SSI took the lead early, launching 12 games in 1981. Some of these games were tabletop wargames with a digital component—their boxes full of tokens, maps and thick manuals—but others, including Computer Bismarck, featured AI opponents and could be played entirely on a computer.

Eastern Front (1941), published by Atari in 1981, immediately made its contemporaries seem antiquated. It was one of the first great leaps forward in strategy gaming, presenting players with a single year of Operation Barbarossa, the German invasion of the Soviet Union, where everything from troop morale to the weather played a role. It was meaty, complex and took advantage of the platform instead of trying to work around it.

Atari had been dubious at first. Designer Chris Crawford had to go through the Atari Program Exchange, which allowed anyone to submit games that, if approved by Atari, would be sold on its mail order catalogue. It became one of APX’s most successful games, making Atari immediately rethink its position on publishing wargames.

The biggest gaming news, reviews and hardware deals

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

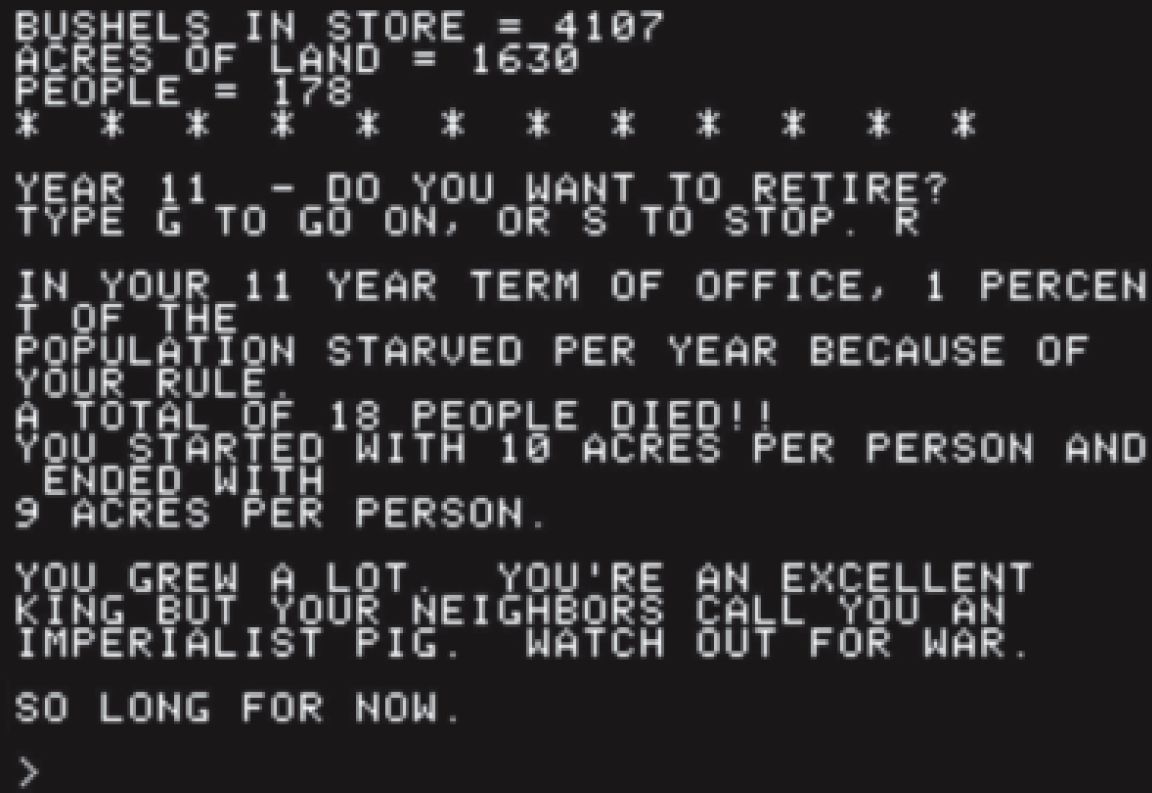

A text-based management game that tasked players with distributing resources to their citizens, Hamurabi was a strategy precursor that could be found in schools and on mainframes in the ’60s. Originally known as The Sumer Game, it was rewritten in BASIC and spread to microcomputers in the ’70s. Unfortunately it was more like maths homework than a game. Hamurabi proved to be popular with prospective programmers. After being published in BASIC Computer Games, a collection of type-in programs, people started making custom versions. These programmers included Walter Bright, who was originally working on a Hamurabi game before creating the Civilization progenitor, Empire.

Wargames based on the Second World War didn’t have the battlefield to themselves. 1983’s Reach for the Stars tasked players with dominating the galaxy with a powerful economy and lots of fancy sci-fi technology, not just big fleets. It had most of the hallmarks of a 4X game—explore, expand, exploit and exterminate—a decade before the term was coined. Reach for the Stars was developed by Strategic Studies Group, an Australian wargame studio, but SSI and Avalon Hill were both playing around in space as well. SSI’s Cosmic Balance II and Avalon Hill’s Andromeda Conquest both contained 4X elements, but they were primarily focused on combat.

Strategy games still didn’t venture too far from their roots, but by the mid ’80s the landscape was almost as vibrant as it is today. At the same time Reach for the Stars unwittingly became the first 4X game, Nobunaga no Yabou launched in Japan, starting a grand strategy series that continues today. Two years later, the same developer, Koei, released Romance of the Three Kingdoms, another grand strategy affair, but this time set during a different historical period, beginning another long-running series that’s also still kicking. Koei took a holistic approach to empire-building, with harvests and peasant loyalty mattering just as much as armies.

Not every conflict involved clashing armies. M.U.L.E. pitted players against each other in a game of greed on an offworld colony. The eponymous M.U.L.E., a cute AT-AT-inspired hauler, harvested resources, which could then be used, sold or hoarded. There was room for cooperation, competition and plenty of backstabbing, making it a compelling multiplayer game for the few that bought it. In 2016, Civilization IV designer Soren Johnson developed a considerably more successful spiritual successor, Offworld Trading Company.

Throughout the ’70s and ’80s, Walter Bright was intermittently working on Empire, initially inspired by Risk. In 1983 he released it commercially. He sold two copies. Bright released a new version for PC the next year and Empire found its audience, along with a publisher in 1987. Like its inspiration, it was a game of conquest, but there were hints of management, with conquered cities being tasked with building various units, from infantry to aircraft, and an exploration phase where players could push back the fog of war. The latter struck a chord with a pair of strategy designers, Sid Meier and Bruce Shelley.

Strategy games and RPGs have long been chummy, perhaps thanks to them both originating on tabletops, spawning countless cases of hybrids. 1984’s Lords of Midnight could be played like an RPG or a wargame, with the hero either going on an adventure to destroy a magical MacGuffin or raising an army of warriors and wizards to storm the Witchking’s citadel. The ’90s had the likes of King’s Bounty and its successor, Heroes of Might and Magic, where heroes led armies across fantasy lands, fighting tactical battles, besieging castles and levelling up. There was a hint of city-building and empire management, but the character progression and exploration owed everything to RPGs.

MicroProse, founded in 1982 by Sid Meier and Bill Stealey, wasn’t initially a strategy game developer. Its first three games, all designed by Meier, comprised a dogfighter, a platformer and a shooter. A year later, Meier released his first strategy game, NATO Commander. Like Eastern Front, armchair generals had to worry about morale and external factors, but NATO Commander had the additional wrinkle of playing out in real time.

After NATO Commander, Meier bounced between genres again, until, in 1985, he designed Crusade in Europe, his second wargame, and the first in the Command series. It was heavily based on NATO Commander, and so the legacy of Eastern Front continued. Then came Pirates! and Covert Action and even more flight sims, and along the way the games started to pick up Meier’s name. It wasn’t just Covert Action, it was Sid Meier’s Covert Action. By 1990, Meier’s name was plastered on a lot of boxes, spread across a lot of genres. He and Bruce Shelley had just finished the management titan, Railroad Tycoon. Meier was itching to do something bigger. Managing a train company or commanding an army wasn’t enough. The pair had its eyes set on something grander: the entirety of human history.

Civilization was a behemoth. It generated entire worlds on which various historical civilisations spread out and inevitably clashed. But it wasn’t always adversarial. Though Civilization may have been inspired by wargames like Empire, Meier and Shelley also looked towards more peaceful games, like 1989’s SimCity. It was as much about improving a civilisation with wonders and buildings as it was tearing across the map, wiping everyone out. You could engage in diplomacy, research new technology or reform your government. It kept people playing for one more turn, and then another. And it was almost an RTS. Meier tested it out, but ultimately found that it wasn’t accessible. Civilization had so many systems that players needed to wrap their head around, and a turn-based game gave them more time to parse everything.

Across only a few years, MicroProse released a string of games that would go on to define strategy for decades. In the wake of Civilization came games like Master of Orion, the first game to receive the 4X moniker. It did for space what Civilization did for Earth, setting a high bar for future space outings. There was Master of Magic, too, which transposed the 4X formula to a fantasy setting where wizards built cities, researched spells and squabbled over magical worlds. The battles played out on isometric maps, while the wizards were like RPG characters; they were mutable and able to learn new traits.

SSI’s Panzer General did away with the notion that wargames had to be complicated, hard-to-parse artefacts from tabletop gaming’s past. It was actually accessible. There was still so much to get stuck into – it was no less of a wargame just because it was welcoming. On top of logistical conundrums and combined-arms assaults found within each World War 2 scenario there was a campaign layer that threw some persistence into the mix. Units gain XP and battle performance had an impact on the state you’d be in when you started the next scenario. Panzer General led to sequels, an excellent spiritual successor, Panzer Corps, and the even more accessible, but also simpler, Unity of Command.

In 1994, MicroProse published UFO: Enemy Unknown, or X-COM: UFO Defense in North America, an elaborate tactical game full of Cold War tension and alien invasions. It was just the latest in a long line of tactical games from Julian Gollop. Rebelstar, Laser Squad and Chaos: The Battle of the Wizards saw Gollop experiment with different settings and systems, but while their influence was visible in UFO, it proved to be much more ambitious than anything that had come before.

Players ran X-COM, a unit specialising in dealing with an extraterrestrial menace. There was a strategy layer, the Geoscape, where the day-to-day running of the organisation took place, and then a tactical layer that took over during missions. It required no small amount of mental agility. One minute you’d be worrying about funding, then next you’d be commanding a squad of soldiers investigating a UFO crash site. It was tough, soldiers got killed off or left behind, and a palpable sense of dread accompanied every mission.

The original concept was a sequel to Laser Squad, with two players duking it out in turn-based tactical firefights. But MicroProse was all about big games. Civilisations that lasted for thousands of years, sprawling space empires, wizards fighting over multiple worlds—Laser Squad II didn’t exactly fit the bill. The first change was the theme, at the suggestion of MicroProse. UFOs were very in. To match the scope of games like Civilization, Gollop and his brother Nick, UFO’s co-designer, introduced the Geoscape and more big-picture management wrinkles. That management element not only made UFO larger than Gollop’s earlier games, it became almost as integral to the series, and its imitators, as the dense tactical combat.

A Civilization sequel was inevitable. There was a hunger for strategy games, and other companies had already made successful iterative sequels. MicroProse gave it the green light. Civilization II, or Civilization 2000 as it was originally called, established the tradition of each game having a different lead designer. Brian Reynolds, who had previously designed Colonization, a Civ-style game of colonising the New World, became Civilization’s second lead designer. Reynolds made a new tech tree, expanded the diplomacy system and completely overhauled the interface. (Ed: You can read the fascinating history of Civ’s lead designers in our piece on the complete history of Civilization.)

MicroProse was bought by Spectrum Holobyte, and the new bosses weren’t very interested in Civilization II. It may have been the sequel to a groundbreaking game, but it was marketed halfheartedly. Word of mouth came to the rescue, however. The second Civ was a huge success, paving the way for yet more sequels, spin-offs and, in a strange case of role reversal, board games.

Meier, along with Brian Reynolds and future Civilization III designer Jeff Briggs, left MicroProse in 1996. Together they founded Firaxis. With its second game, after Gettysburg!, the fledgling studio charted the next step in civilisation. Briefly unable to work with the Civilization licence, Firaxis looked to the stars for inspiration. Alpha Centauri took over from where Civilization ended, or at least one of the places where it could end: people leaving Earth behind for a new life on a new world.

Don’t trust anyone who doesn’t smile when they think about this turn-based artillery romp. Worms has thrown in classes and physics, and even had a brief misguided dalliance with 3D graphics, but ultimately it’s always been about one thing: murdering worms. It’s was an all-time great multiplayer game and developer Team17 continues to get a great deal of mileage out of its clumsy invertebrates and their ever-expanding cartoonish arsenal. Exploding sheep, holy hand grenades, concrete donkeys, missile strikes, even Street Fighter’s dragon punch – the only issue is how long it takes to pick one. Luckily Worms also kept things ticking along, letting you set some much-needed time limits.

It was, and still is, a remarkable 4X game. Warring nations were replaced by complex factions that identified with ideologies, not flags. While Civilization’s leaders had the suggestion of personality, Alpha Centauri’s seven factions (14 with the expansion) and their chatty leaders oozed character. And it was blessed with unparalleled flexibility. You could build an isolationist science commune guarded by elite, enhanced soldiers and tachyon shields, or immediately set out to unite humanity, gathering support from the other factions and pushing your agenda in the Planetary Council.

The sci-fi conceit opened the doors to transhumanism, mind-control and ocean cities, but it was never gratuitous. Guided by a narrative that led to the game’s ultimate victory, Transcendance, Alpha Centauri was as cohesive as it was ambitious. It might not have been a Civ game, but it was more than a worthy successor to Civilization II, and the pinnacle of ’90s turn-based strategy.

To find the first strategy games that were truly distinct from their tabletop forebears, we have to rummage through the annals of real-time strategy. While turn-based games dominated strategy throughout the ’80s, the precursors to the RTS were appearing as early as 1982, with SSI’s Cytron Masters. It was a simple real-time tactics game where players used energy created by generators to build robots and fight each other, clashing on a small grid full of bunkers and mines. In combination with games like Utopia, Modem Wars and NATO Commander, it laid the groundwork for a new kind of strategy game.

Herzog Zwei is usually hailed as the first RTS. It’s certainly the earliest that still looks recognisable today, and it’s responsible for a multitude of mainstays. Released for SEGA’s Mega Drive in 1989, it featured a transforming mech that could flit around the battlefield as a jet, but also turn into a ground unit and batter enemies. It was through this mech that players interacted with the battlefield, using it to transport troops between bases and fights, with the ultimate goal being the destruction of the enemy base. Units could be given orders, sending them to patrol a specific area, occupy a base or attack an enemy and when they took damage, it was up to the player to heal them. It had micromanagement, a resource economy, bases and every moment of it took place in real time—it was an RTS. Unfortunately, it wasn’t a very successful one.

Despite not setting the world on fire, Herzog Zwei’s impact was still significant. It influenced the designers of just about every important RTS of the ’90s, and more recently it’s been credited with being a precursor to the MOBA genre. There’s a shared philosophy that prioritises speed and mobility, and of course there are the similarities between Herzog Zwei’s mech and future heroes and summoners. We’re still 14 years away from Defense of the Ancients.

Herzog Zwei may have kickstarted the RTS, but it was Westwood Studios’ Dune II, three years later, that popularised it. The conflict was framed as a war over resources, with houses Atreides, Harkonnen and Ordos fighting over spice, the drug around which the Dune series orbits. Scarcity drove the action, forcing the houses to compete over spice deposits that could be turned into credits, then buildings, then troops. It was constant escalation, and any time spent faffing around was time your enemy was spending getting rich and strong.

Into this war, Westwood flung environmental threats like Dune’s infamous sandworms and shitty weather, powerful faction-specific units, a campaign map that let you pick missions—it wasn’t all brand new, but it was the first time all of these things had been put together in one real-time strategy game. The cycle of gathering and expansion that sat at its heart became the blueprint for almost every future RTS.

Dune II did not set off an avalanche of imitators, but in 1994 Blizzard released its first RTS, Warcraft: Orcs & Humans. As Silicon & Synapse (and briefly Chaos Studios), the developer was known for SNES games like The Lost Vikings and Rock n’ Roll Racing, but noticing a conspicuous dearth of RTS follow-ups to Dune II, it decided to fill in the gap. Warcraft took the base-building, resource-gathering and real-time scraps from Dune II, but set it amid a war between orcs and humans in the fantasy land of Azeroth.

The Warcraft universe can’t be contained to a single medium these days, and the story of its warring factions and demonic invasions is covered in books, comics, a movie and, of course, the world’s most popular MMO. Back in 1994, Blizzard was winging it. The story of Warcraft was conjured up at the last minute, but even then there was a hint of the universe’s trademark tongue-in-cheek charm and occasional subversiveness.

Alongside its campaign, Warcraft had a secret weapon: online multiplayer. Skirmishes could be fought over LAN or online between two players. Behind the orcs and knights were devious humans, sneaky and tricky. Long before World of Warcraft enchanted millions of players, Azeroth was a multiplayer-friendly place. Orcs & Humans set a precedent, not just for Blizzard but most RTS developers. Blizzard would remain the master of this arena, however, building online worlds and esports and communities spread across half a dozen constantly updated games.

Every soldier in Close Combat, Atomic Games’ real-time wargame, was an individual. They were part of a squad, but each had their own simulated mental and physical condition that changed their effectiveness in combat. In extreme cases, they’d become incapacitated or fly off the handle. It was a focused version of a wargame, inspired by Squad Leader. While C&C and Warcraft had accessible interfaces and units that did what they were told, Close Combat was dense and full of badly-behaved soldiers. The series persists, marching to the beat of its own drum. The upcoming Close Combat: The Bloody First will be the first in the series to use 3D graphics.

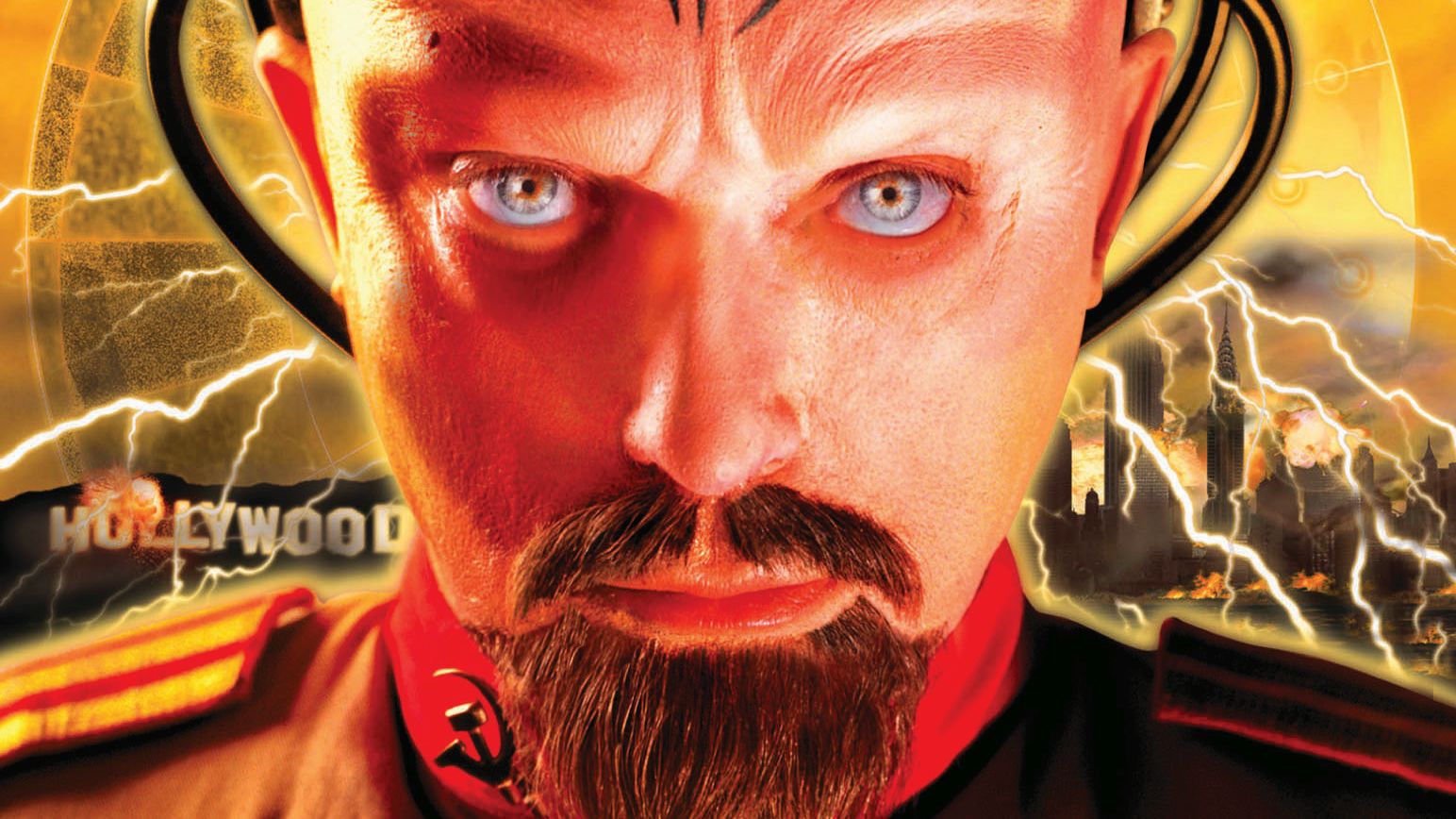

The nascent RTS genre might have seemed quiet when Warcraft was released, but inside Westwood Studios designers were furiously working on their own follow-up to Dune II. The result, appearing in 1995, was Command & Conquer. You’ve immediately started thinking about the FMV scenes, haven’t you? Even when Westwood had the budget for fancier cutscenes, the FMVs remained. It’s part of Command & Conquer’s DNA, but originally it was done out of financial necessity, using Westwood employees and a single professional actor.

The war between the GDI (the good guys) and the Brotherhood of Nod (the very, very bad guys) brought with it a whole host of wonderful new toys to play with. Stealth vehicles, explosive commandos, flamethrower tanks—both factions had their exotic units, though Nod more often ventured into the weird. The diverse roster of units and a faster pace ensured that, while Command & Conquer still stuck closely to Dune II’s gameplay loop, complete with a new alien resource waiting to be harvested, it wasn’t retreading too much old ground.

Blizzard responded with Warcraft II: Tides of Darkness. Since it was in development when Command & Conquer appeared on the scene, it was able to compete directly with all of the fancy improvements Westwood had introduced. A few ideas were pinched, as well. Command & Conquer let you click and drag the mouse to select multiple units, so did Warcraft II. Command & Conquer had four-player multiplayer, so Warcraft II expanded it to eight. Blizzard also developed a new fog of war system which differentiated between areas you hadn’t visited and area’s that simply weren’t in your line of sight. Unexplored parts of the map were completely covered by the fog of war, while areas that your faction had explored but were out of your line of sight were coated in a grey filter that hid units and buildings.

Warcraft II also saw Blizzard start taking story more seriously. Chris Metzen, later Warcraft III’s creative director, was brought on as a writer. He helped make sense of Blizzard’s fantasy universe, while also working on Warcraft II’s mission design. Westwood and Blizzard weren’t just building competing strategy games, they were nurturing worlds.

Command & Conquer may have shown Warcraft a thing or two, but Blizzard had learned its lessons well. Warcraft II was another hit for the studio. Everyone expected Command & Conquer II to follow, but instead Westwood went back in time. Command & Conquer: Red Alert dialed up the absurdity with a time-travelling Albert Einstein and an alternate history where Hitler never rose to power and the Soviet Union was poised to swallow up Europe. It embraced its ridiculous conceit with even greater gusto than its predecessor, resulting in the Allied and Soviet factions boasting even more unusual and varied units and fortifications. There was something especially reassuring about having a wall of Tesla Coils protecting your base. They were great bug zappers.

There were expansions and ports and more Warcraft and Command & Conquer games just around the corner, but RTS games were also flourishing outside of this rivalry, as well as because of it. There was the Command & Conquer-inspired Dark Reign and its complicated line of sight rules and terrain, while Z rather boldly did away with the gathering cycle, and even mediocre games like KKnD were doing interesting things with automation.

God simulators and management games have been a frequent source of inspiration for strategy games. Populous and SimCity, both of which appeared in 1989, are partly responsible for an astonishingly broad array of games, from Civilization to Dune II, and there hasn’t been a time where there wasn’t some intermingling going on. With games such as Anno, Age of Empires, The Settlers and Dungeon Keeper the lines continued to blur. There was city-building and economic management, but there were troops and real-time battles and territorial struggles, too. And it was a formula that worked extremely well: all of them spawned sequels and, in some cases, are still around today.

The legacy of Dune II, even by 1997, was hard to avoid, but new games were sprouting from other evolutionary branches. Total Annihilation put its own spin on just about everything, from streaming resource generation to its powerful, multipurpose commander unit. Yes, it was still ultimately a game of acquiring resources and using them to fund a big ol’ army that you’d then march into a base and unleash, but no other game made managing all this infrastructure and the army that thrived on it so fraught with tension. It necessitated planning and hindsight and the willpower to avoid going all out and constructing a gargantuan and ultimately energy-draining force of murderbots. A nifty physics system and 3D terrain was just the icing on the cake. 1997 was generally a great year for more unconventional RTS games. Bullfrog’s Dungeon Keeper blended management, construction and real-time scraps into a chimera where players wore the mantle of villain, nurturing a dungeon and murdering pesky heroes. The cursor was replaced by a hand that could slap lazy imps and pick up monsters, dropping them in rooms or near fights. To recruit these monsters, you had to seduce them into your dungeon by providing them with accommodation and food, and each needed to be paid from your treasure hoard. Management and RTS games already had plenty of shared DNA, and the different layers proved to be complementary. And thank goodness it was funny! Running an actual dungeon sounds pretty horrible, but when it’s filled with chickens, comic relief imps and dopey heroes, it’s a lot more palatable.

Sid Meier and Bruce Shelley had decided against making Civilization an RTS, but with Ensemble Studios’ Age of Empires, Shelley took a commendable crack at it. The scale was smaller and the timeline covered the Stone Age up to the Iron Age rather than all of human history, but the fundamentals were all present. There were 12 historical civilisations to choose from, technology to research, even wonders that functioned much in the same way as Civilization’s. But where Civilization was a sprawling, slow-burning game, Age of the Empires was a race.

With a brisk pace and resource gathering being a priority, the Civilization elements were ultimately overshadowed by systems inspired by the likes of Command & Conquer and Warcraft—although not when it came to combat. It was all just a bit messy, not helped by poor pathfinding and AI niggles. There were plenty of different units, complete with plenty of upgrades and historical progression, but when armies actually collided there wasn’t much room for tactics. The comparisons with popular games on both sides of the strategy aisle and the grand historical setting served it well, however, spawning a series and plenty of admirers.

Blizzard was taking its time with its next RTS. Azeroth had been swapped out for an also-pretty-familiar sci-fi setting, but it otherwise hewed too closely to Warcraft. Feedback inspired Blizzard to do some serious remodelling, a process that took two more years and eventually gave the world StarCraft in 1998. It broke new ground everywhere, with its mission design, its story and especially in the way that it gripped players, to the point where the original still has a thriving community today and remains a phenomenon in South Korea. Its greatest achievement, however, was the magic it worked with asymmetry.

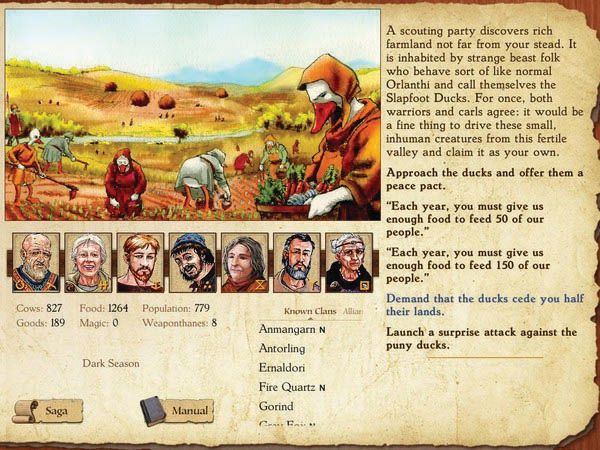

It’s good to be king. It’s also a great deal of work. King of Dragon Pass, released in 1999, put you in the shoes of a clan leader and left it up to you to completely mess things up. Do you slaughter some intelligent ducks and steal their land? Will you pay a neighbouring clan for a slight made by one of your clansmen? Trade, warfare, farming, diplomacy and religion all fell under the purview of clan chief. Watching your own clan develop and the consequences of decrees play out is a singular delight, and where King of Dragon Pass really excelled, much like Crusader Kings II which arrived over a decade later, was in generating brilliant, unexpected stories.

StarCraft set three extremely distinct factions against one another. The Terrans, Protoss and Zerg each built, gathered and fought differently, and each possessed an entirely unique roster of units. It was a monumental task to balance, but Blizzard kept on tweaking and fiddling even after launch, something the company continues with its games today, trying to get it just right. This asymmetry and fine-tuned balance spawned a competitive scene that persists even now.

People had been waiting for a sequel to the original Command & Conquer since 1995, but it was taking longer than Westwood, which had been acquired by Electronic Arts, anticipated. There were delays, content was cut and it wouldn’t be until 1999 that Command & Conquer: Tiberian Sun reignited the conflict between GDI and Nod. It was a striking but familiar RTS, full of playful sci-fi units and a lighting system that made it look drop-dead gorgeous. The expansion, Firestorm, was Westwood’s final RTS in the Tiberium series. One more Red Alert followed, then a remake of a remake of Dune II. The studio’s final games were a misguided shooter, Command & Conquer: Renegade, and an MMO, Earth & Beyond.

Westwood was a victim of the grim ’00s, and not the only one, but ’99 still had some tricks left, not least of which was Homeworld. Relic’s hauntingly beautiful space RTS was the first truly-3D strategy game. You weren’t stuck staring at a map from one perspective; you could hurtle through space, following your fighters as they weaved their way between enemies, or step back and just soak up the galaxy. The way the ships moved and fought turned battles into arresting ballet performances, accompanied by an exceptional soundtrack. It was a game of vast scale elevated by tiny details. Mining, building ships and fighting were still the top three priorities, but the space arena made even the familiar seem novel.

Throughout the late ’90s, designers had been scrambling to unseat the titans, promising that the next great Civilization or Age of Empires or Command & Conquer was just around the corner. That tactic had diminishing returns; the wars had already been won. The awkward march to 3D had commenced, and not able to rely on the old formulas, designers had started to look to other genres for inspiration. A tumultuous time was looming.

Myth: The Fallen Lords, developed by Halo and Destiny studio Bungie, was an astounding technical achievement when it launched in 1997. It was a 3D real-time tactics game with a 3D camera to match. That alone made it worth taking notice, but Myth also proved just how gamechanging 3D battlefields could be, particularly if they were supported by physics. If an archer missed an enemy, for instance, that arrow still had to go somewhere. Maybe it hit a tree, or another character. Weather, range and elevation all exerted their influence over the tactical scraps, which made it more than a bit tricky, but also unlike any other strategy game around. It’s a great shame that Bungie moved onto other pastures.

Some of strategy gaming’s most influential titles were developed for consoles, but by 2000 the genre had been synonymous with PC for a decade. The launch of the PlayStation 2 saw more and more people drift away from their PCs, prompting Microsoft to make the Xbox, which appeared the following year. It might have looked like a PC, but when it came to traditional strategy games, it was just as hostile an environment as any other console. The audience was shrinking, publishers were becoming increasingly risk-averse and players were coalescing around stalwart franchises.

Out of this came oddities, hybrids, spin-offs and more experiments with 3D maps and cameras, like Massive Entertainment’s real-time tactics game, Ground Control. Similar to Relic’s Homeworld, it gave you free rein of the camera, letting you zoom out for an overview of the battle—though not quite as far, given the smaller scale—and then all the way up to your beefy sci-fi units, watching them from ground level as they bombarded enemy fortifications or stormed bases. It looked great, and it boasted plenty of other noteworthy features, like 3D terrain that could modify accuracy, foliage that could hide troops and customisable units.

At the same time, Shiny Entertainment introduced the world to Sacrifice. In another reality, Sacrifice is probably hailed as an important and influential RTS, but for some reason we’re stuck in the one where it’s more of a brilliant, overlooked curio. With a library that included Earthworm Jim and MDK, Shiny’s games were typically strange and inventive, but the studio had never worked on anything close to a strategy game. That might have been an advantage, as Sacrifice ripped apart RTS conventions.

Sacrifice looked nothing like an RTS, borrowing its perspective from third-person action games and keeping the screen devoid of clutter. Players directly controlled just one character, a wizard, who could cast apocalyptic spells and summon all sorts of colourful, magical units. The summoned creatures followed the wizard around, and they could be given orders or put into formations. Instead of fussing with resources, buildings and large armies, all of your concerns were right there in front of you: the wizard and their crew of weird minions. And it looked incredible for the time. It was a surreal, broken dreamscape that looked like it leaked out of the brain of Salvador Dalí or Hieronymus Bosch. The unit design was just as strange, featuring a large menagerie of outlandish beasties that could be thrown into battle.

Like the wargames of the ’70s and ’80s, collectible card games have increasingly been going digital. Some, like the wildly popular Magic: The Gathering, started out as physical games before digital spin-offs cropped up, while others, like Hearthstone, were developed as videogames from the ground up. While the settings, rules and mechanics often differ a great deal between them, these strategy-adjacent games task players with creating decks of armies, heroes, buildings, spells or just broad concepts. Hybrids have been appearing too, like Card Hunter, which mixed tabletop RPGs with CCGs and tactical combat, and Valve’s upcoming Artifact, inspired by Dota 2.

These new strategy games were posing interesting questions about what ingredients the genre really needed to succeed, and what could be thrown away or reconsidered. Majesty: The Fantasy Kingdom Sim, for instance, asked if we really needed direct control at all. Instead of commanding units, players had to tempt heroes to set up shop in their town by providing the appropriate facilities, and then encourage them to go and solve nearby problems by creating quests and rewards. Essentially, you were a Dungeon Master, sending heroes out on adventures to explore a new part of the world or murder some pesky monsters.

Established franchises were getting smaller, but still notable, shake-ups. Age of Mythology applied the Age of Empires formula to ancient myths and legends, throwing monsters, magic, gods and heroes into the mix. Command & Conquer: Generals, the first post-Westwood game in the series, switched the setting to another near-future crisis, ditched harvesters and went 3D. Civilization had also returned home to its creator after some drama, litigation and Activision’s Civilization: Call to Power. Civilization III would prove to be a divisive instalment, but it also introduced the culture system, changing the ways civilisations could expand and opening up new paths to victory that didn’t involve conquest.

In 2002, Blizzard returned to Azeroth with a story of unlikely ententes, demonic armies and superpowered heroes. Warcraft III: Reign of Chaos was a fantasy epic not just driven by armies and resource-gathering, but by sympathetic, multifaceted characters whose stories continue to develop today. The plot actually started out as an adventure game, Warcraft Adventures: Lord of the Clans. With it, Blizzard wanted to chart the life of Thrall, the eventual leader of one of Warcraft’s factions, the Horde. It was ultimately shelved, but the story of Thrall got a second life in Reign of Chaos.

The importance of these heroes went beyond the narrative. When Warcraft III was first announced in 1999, it was a strategy RPG, reminiscent of King’s Bounty or Heroes of Might and Magic. A lot of the RPG elements ended up on the cutting room floor, but the role of heroes persevered. Heroes were powerful units who grew as they gained experience, developing handy new abilities. They could equip magical gear, too, and even do a spot of shopping to give them an edge. Sure, they were surrounded by small armies and fighting in a worldshaking war, but these were adventuring RPG heroes.

TV shows featuring videogames are usually rubbish, but not Time Commanders. The BBC show gave teams of four a historical army to lead and an enemy to fight, with captains barking out orders and the rest of the team relaying them to staff from the show. There were planning sessions, teams poring over maps and tons of heated discussions, but the thing that brought the battles to life was our pal Rome: Total War. Products can’t be promoted on the BBC, so the game wasn’t mentioned, but it was the show’s linchpin. All of the Time Commanders’ orders were acted out on a modified version of the game, and it looked incredible. Only two series were produced, but it was briefly resurrected in 2016.

It was still undoubtedly an RTS, but amid all the base-building and troop management were nods to RPG design, such as quests and NPC enemies that were hostile to every faction. Because they’d persisted through all the other changes, they weren’t novelties; they were built into the game’s foundations. Thanks to these innovations, as well as Blizzard’s brilliant balancing and clever mission design, Warcraft III and its expansion, the Frozen Throne, became seminal strategy games.

Frozen Throne marked the end of Warcraft, at least as a strategy franchise. The critical and commercial success of Warcraft III, instead of paving way for yet more RTS games, set the scene for its MMO successor, World of Warcraft. Its strategy legacy is just as important, however, with Warcraft III at least being partly responsible for the birth of multiplayer online battle arenas, or MOBAs.

Defense of the Ancients was a Warcraft III mod that gave players direct control of their hero, and nothing else. Armies and bases were still integral, but there was no construction, nor could these armies be commanded; instead they automatically marched down lanes, attacking enemy towers or any other units they came across, until they reached the opposing base. Defense of the Ancients was based on a StarCraft custom map, Aeon of Strife, but used Warcraft III’s RPG hero systems to create the blueprint for the vast majority of MOBAs that would follow in its wake.

Though it would take several years for the popularity of Defense of the Ancients to inspire commercial imitators and spiritual successors, plenty of variants were developed by other Warcraft III modders. Kyle ‘Eul’ Sommer developed the original mod, but when Sommer ceased updating his version, new mods filled the vacuum. DotA: Allstars attempted to capture the best of this burgeoning genre of mods, throwing an assortment of heroes from across multiple variants into one map. Allstars grew, and it eventually passed into the hands of eventual League of Legends designer, Steve ‘Guinsoo’ Feak.

When Civilization codesigner Bruce Shelley embarked on Age of Empires, it was going to be a cross between Civ and RTS games like Warcraft and Command & Conquer. Those lofty ambitions were never quite matched by Age of Empires, but Rise of Nations got a lot closer. Also designed by a Civ alumnus, this time Brian Reynolds, it made all of human history an RTS playground. Reynolds threw lots of concepts more common in turn-based games into the mix, including territory, attrition and overseeing multiple settlements, but it was all manageable, even with the real-time pace. It looked poised to usher in an exciting new era of RTS games, but despite being brilliant, it never did.

Feak developed a lot of new features, heroes and items, but perhaps the most important thing to come out of Allstars was its competitive community. Tournaments had started kicking off, the forum was a constant hive of activity, and the mod was always being tweaked and balanced by a growing team and a community quick to give feedback. Allstars’ popularity was unprecedented, and it would sit at the top of the pile until 2009, when League of Legends launched. Valve’s standalone sequel, designed by another DotA modder, generally known just as IceFrog, followed soon after.

Total War marched onto the strategy battlefield in 2000, mixing grand strategy and gargantuan real-time tactical battles with authentic historical settings. Shogun: Total War got the ball rolling, though it was almost a very different game from the one that gave birth to the series. Creative Assembly had been developing EA Sports titles when it got an opportunity to work on a new title for the publisher; the catch was that it had to be an easy win. At the end of the ’90s, real-time strategy couldn’t have seemed like a surer thing, thus the studio started work on its very first RTS.

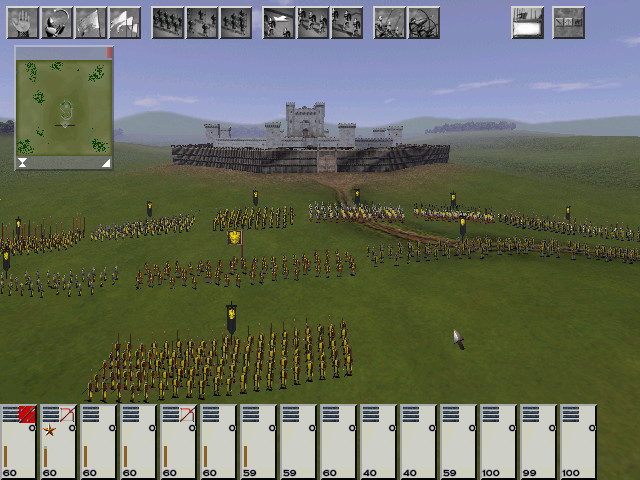

Shogun quickly grew beyond expectations. With its 3D battlefields, thousands of warriors and an unshackled camera, it seemed far-removed from a Command & Conquer knock-off. Once the team had settled on the Sengoku era and an approach to combat that was both historical and tactical, a military historian was brought in to make sure everything felt right. Creative Assembly’s rule of authenticity over accuracy was established early on, so Shogun wasn’t beholden to history, but it was convincing enough.

The campaign layer was a later addition. The real-time scraps needed something to glue them together, but instead of building a linear campaign that led players from one battle to the next, Creative Assembly crafted a map of Japan full of provinces, fortresses and warring factions. All the big strategic decisions took place on this turnbased map, from diplomacy to troop movement. With those two layers combined, Total War had its formula.

Medieval: Total War followed in 2002, expanding the army size to a whopping 10,000 troops and setting the wars amid a massive map of Europe and the Middle East. Medieval also introduced sieges, though with mixed success. Of the first trio of Total War games, it’s the third and final entry that set hearts aflutter. Rome: Total War is where the series started to get dense, with its civil wars and Senate missions and family trees. It was no longer a Risk-inspired board that linked fights together, but a complicated 3D map that was supported by enhanced trade and management features. Though the tactical brawling remained the star, it was the first campaign that seemed like it could exist as a standalone game.

There was a good reason why the battles were always in the limelight, of course. They looked incredible. The new 3D models made armies seem like real, tangible things, and when these armies clashed it looked like no other game. It was almost possible to feel the impact of these charges, especially when they involved thundering war elephants and many, many unfortunate soldiers being flung into the air. In the 14 years since, Total War’s battles have become more and more striking, but Rome still looks incredibly impressive.

Though all these hybrids were appearing, Relic was able to prove that there was still room for a more single-minded RTS. Following a second space outing with Homeworld 2, the studio set about bringing the grimdark universe of the 41st millennium to life. Warhammer 40,000: Dawn of War flung Space Marines, Eldar, Orks and Chaos at one another in the miserable battlefields of Tartarus. The name should have been a dead giveaway.

There’s always a new Warhammer game knocking around, whether it’s inspired by the fantasy universe or its 40K sibling, and not surprisingly, quite a few of them have been strategy games. The licence hasn’t always been used well, but there is variety. Even just in the last few years we’ve seen claustrophobic turn-based tactics like Space Hulk, massive wargames like Warhammer 40,0000: Armageddon, grand strategy in the form of Total War: Warhammer, and even a 4X game, Warhammer 40,000: Gladius, which reimagined the genre without diplomacy. If you’ve got an idea for a new Warhammer game, give Games Workshop a shout; it will probably let you take a crack at it.

Relic maintained a lot of the concepts from Games Workshop’s enduring tabletop game, bending them around a fast-paced RTS. Your typical RTS resources, for instance, didn’t feature in Warhammer 40,000; sending out gathering units or fiddling with your economy wasn’t really in keeping with the hyper-aggressive setting. Dawn of War used resources more to push players into conflict. Requisition points were required to plonk down buildings and recruit squads, but instead of being gathered, these were generated by capturing and holding strategic points.

The small number of strategic points ensured there was an endless supply of lively battles. Instead of hunkering down and protecting your base, you had to strike out, ordering your squads to travel all over the map, not just to find strategic locations, but to reinforce them, protecting them from enemy assaults. A morale and cover system made its way over from the tabletop game, as well. It was a tactical layer that necessitated a bit more thinking and a little less screaming, “Blood for the Blood God!”

With Company of Heroes, Relic swapped the grim battlefields of Tartarus for Normandy. The things that had set Dawn of War apart, Relic ran with. And it ran far. Morale and cover were refined to the point where playing an RTS without these systems suddenly seemed bonkers. Every squad was this squishy, vulnerable group of soldiers which could be wiped out at a moment’s notice, or broken and forced to flee for their lives. But with the right commander, they could do wonderful things.

A tank might be able to make short work of some infantry, but hide footsoldiers behind a wall, wait for that tank to roll by, and you’d get a shot at its weak points. Or the tank could just smash the wall and kill all your lads. The Havok physics engine fuelled Company of Heroes’ destructible maps, so units couldn’t get too comfy. Luckily, cover was always clearly marked, not just showing you where your units could seek protection, but exactly how protected they would be. There was also an unusual delineation between troops and weapons. A weak squad of riflemen, for instance, could capture an anti-tank gun, letting them lock down a road all on their own. Infantry could pick up abandoned weapons and commandeer them from enemies, making them extremely versatile.

Company of Heroes often seemed more like a squad-level wargame than an RTS, evoking the likes of Close Combat rather than Command & Conquer. There were even supply lines, though they were heavily abstracted. Like Dawn of War, players fought over capture points, but each point was connected to the rest, simulating a supply line. Taking out just one part in the chain could destroy another player’s economy and force another confrontation. It wasn’t like taking out an enemy harvester—the only way they could fix it was by taking back that location, even if it seemed hopeless. There was real drama behind the battles.

Company of Heroes heavily drew from Band of Brothers, 2001’s HBO miniseries, and was thick with the show’s atmosphere. The ruined countryside and villages of Normandy were unlike any other battlefields. Each map was elaborate, dynamic and, of course, incredibly dangerous, full of places for snipers and mortar teams to hide. It was emotionally resonant, too. The pockmarked roads, the destroyed European towns, the terrified men trying to escape machine gun fire—even when it was explosive and exciting, a melancholy cloud loomed over everything.

Total Annihilation’s unique approach to RTS games in the ’90s didn’t lead to many imitators, which is possibly why Chris Taylor decided to make a spiritual successor to his own game. Supreme Commander took Total Annihilation’s foundation and then made it bigger. Huge. It was no wonder that it was an early adopter of dual-screen support. Recent years have seen a greater yearning for a Total Annihilation-style game. Planetary Annihilation, with its conflicts taking place across solar systems, upped the scale, but lost something by trying to appeal to the esports crowd. 2016’s Ashes of the Singularity was the latest in the line, though hopefully not the last.

It wasn’t enough to slow, let alone stop, the decline of the RTS. There were still notable titles appearing but more often these were sequels and spiritual successors. A year after Company of Heroes launched, we saw Total Annihilation resurrected in the form of Supreme Commander, designed by original creator Chris Taylor, while Massive Entertainment followed up Ground Control 2 with the superb World in Conflict. RTS games were still alive, but only just. Today, the most popular RTS is still StarCraft II, which launched in 2010. Its excellent expansions and huge multiplayer support are responsible for its longevity, and it helps that it features some of Blizzard’s best mission design, but it’s still very familiar.

Elsewhere in the strategy genre, people could satisfy some of their turn-based cravings with Total War, but empire-building wasn’t quite what it used to be. Wargames had become a niche satisfied by a few specialist publishers. In the 4X realm the long-awaited sequel to Master of Orion II launched to disappointed grumbling in 2003, and aside from a few exceptions like Galactic Civilization, new titles became increasingly hard to find.

There were bright spots amid the gloom. In 2005, Civilization IV saw designer Soren Johnson re-evaluate everything, right down to the series’ foundations. Along with being the first 3D Civilization game, it was also the first to be built from the ground up as a multiplayer game. It introduced upgradeable units, a religion system and more accessible modding, giving it a second life as a platform for not just new scenarios, but entirely new games. Civilization IV marked the beginning of a new generation of Civilization games, with its successors featuring even bolder redesigns.

Carving out an empire didn’t have to take place turn-by-turn, of course. Sins of a Solar Empire made a great case for 4X games to dip their toes into real-time action, mashing up empire management with gorgeous RTS space battles. You could quickly dash between commanding a fleet of ships, laying siege to an outpost and governing worlds, seamlessly. And where other 4X games could be slow-burning, Sins of a Solar Empire had the pace and aggression of an RTS. Alliances could be forged, but conquest was always on everyone’s minds.

Throughout the ’00s, Paradox Development Studio had been creating some of the most complex and dense grand strategy games around. All of them played out in real time, but with speed controls and liberal use of the pause button. Years could fly by in-game, but equally you could spend hours not moving time forward at all, obsessing over trade deals and assassination plots with your nose buried deep in the menus. The Europa Universalis series, set in the late Middle Ages, is the flagship of the bunch, giving players control over the fate of a historical nation across centuries. There’s the economy to juggle, along with wars, colonial ambitions, religious crises, civil wars and political relationships with countless other nations all across the world.

The success of the first Europa Universalis spurred Paradox on to create more grand strategy romps, including Hearts of Iron, set during World War 2, and Victoria, which honed in on the industrial revolution and the dramatic political and social changes that the era brought with it. All of them were liberating simulations that let players chart their own course through history, creating bizarre alternate realities that only made sense if you’d read the after action report. They were also incredibly rough around the edges, buggy and a nightmare for newcomers to get their teeth into.

Sporting a new engine and an extra layer of polish, Crusader Kings II was a turning point for Paradox. Though its predecessor had been tepidly received in 2004, Crusader Kings II found a much larger audience, who then spread bizarre stories and anecdotes of the histories of their characters and dynasties. Instead of running a nation, players controlled the leader of a medieval family; you might be a powerful empress or a count with no vassals and no ducats. Through political marriages, wars and Choose Your Own Adventure-style events, you could end up losing everything, including your head. Or you could kill your spouse, marry your horse, leave everything to your children and flee to another continent to start a new, more enlightened kingdom. Crusader Kings II could get weird, especially when you throw in expansions that include Aztec invasions of Europe and Satanic cults.

Paradox’s peculiar grand strategy RPG arrived during a more hopeful time for strategy games. The first decade of the 21st century had not, when all was said and done, been particularly kind to the genre, but things seemed to be slowly changing. More new 4X games were appearing, like the extremely complex Distant Worlds and the Master of Magic-inspired Warlock: Master of the Arcane. After overextending with the massive and ungainly Empire: Total War, Creative Assembly returned with a focused and refined standalone expansion, which it then followed up with arguably the best game in the historical series, Total War: Shogun 2. Then, in 2012, aliens invaded Earth again.

Developed by Firaxis, XCOM rebooted the ’90s tactical titan, UFO: Enemy Unknown. It had been a whopping 15 years since X-COM: Apocalypse, the last successful X-COM, with the proceeding years only seeing a mixed bag of spin-offs, culminating in 2001’s completely forgettable third-person shooter, X-COM: Enforcer. Though it was designed without series creator Julian Gollop, XCOM nonetheless felt like a return to form. More than just a modern update to the original game, it was a slick reimagining. The large, loose teams were switched out for specialised squads full of soldiers who could be obsessively customised, while randomly generated maps were replaced with hand-crafted environments. There was streamlining, but there was also plenty of expansion.

Command & Conquer defined a generation of RTS games, but after Westwood was closed by EA in 2003, the series started to lose its shine. EA Los Angeles started strong with the rather different Command & Conquer: Generals, but quickly returned to the Tiberium and Red Alert series. The sequels were well received, but they played it safe at a time when other RTS titles, ones without Command & Conquer’s legacy, were innovating and experimenting. 2010’s Tiberian Twilight veered in the other direction, putting all of its eggs in the multiplayer basket. It proved to be a bit of a misstep, and since then the series has been relegated to browser and mobile games.

XCOM didn’t just appeal to the diehards who had been keeping the flame alive for over a decade, or even just the general strategy crowd; its accessibility and flashy presentation opened the doors wider, but not at the expense of the challenge. XCOM proved to be a demanding game at times, forcing players to make hard choices and sacrifices, but it usually stopped short of being overwhelming—unless you were playing in Ironman mode. That forced commanders to live with their mistakes and decisions, including the loss of a soldier or even entire squads, by only giving you a single save file that got overwritten with every turn.

A lack of publisher confidence had been holding strategy games back for years, but here was XCOM, a niche tactics game, getting lots of attention and launching on everything from PC to mobile. XCOM was published by 2K Games, which had acquired Firaxis in 2005, but publishers were becoming increasingly optional thanks to crowdsourcing, early access platforms and more accessible game development tools. Suddenly it was impossible to keep track of all the new games popping into existence.

Invisible Inc., Klei Entertainment’s espionage-themed tactics game, appeared on Steam Early Access in 2014. It was endlessly inventive; simultaneously an exceptional stealth game and a landmark tactics affair. There was something liberating about its pure-stealth focus. There were no drawn-out gunfights after you’d been spotted. You either used one of your agent’s tricks to get out of the way, or you were done for. Every mission was a randomly generated puzzle that could blow up in unpredictable ways, leading to agents needing rescued or even a playthrough that ended in failure. But it was also a game that begged to be played over and over again.

It wasn’t just independent developers taking advantage of new models like early access. Endless Legend launched on the platform in the same year as Invisible Inc., and quickly set about rewriting the 4X genre. Amplitude’s previous game, Endless Space, had been a competent, Master of Orion-style 4X with an unusual card-based combat system, but it was as sterile as the cold vacuum of space. That wasn’t a problem Endless Legend had. No 4X game since Alpha Centauri had featured such a fascinating, rich set of factions, and here their differences went far beyond ideology or well-written flavour text. Take the Necrophage—they’re an endlessly hungry species of plague-spreading insects, which means they will never make friends with anyone. The Cult, meanwhile, is manipulative and influential, but can’t build cities. There are mages, space marines and even a group of dragons who just want everyone to get along, and each represents a distinct way of playing the game.

Evolutionary dead ends were springing back to life and old franchises were making comebacks. Looking at the sheer variety, it was strange to think that strategy had been looking sickly only a handful of years before. Darkest Dungeon, Homeworld: Deserts of Kharak, Eugen’s Wargame series, Offworld Trading Company, Ashes of the Singularity, Northgard, BattleTech, Into The Breach—the list is vast and features every kind of strategy game imaginable. And while a lot of series have fallen by the wayside, plenty have survived. Civilization is probably immortal by this point, StarCraft continues to be massively popular and Total War now counts the Warhammer fantasy universe among its battlefields. Even tabletop games, where our trip through the history of strategy began, have seen a resurgence. Strategy games are as vital and creative as they’ve ever been.

Fraser is the UK online editor and has actually met The Internet in person. With over a decade of experience, he's been around the block a few times, serving as a freelancer, news editor and prolific reviewer. Strategy games have been a 30-year-long obsession, from tiny RTSs to sprawling political sims, and he never turns down the chance to rave about Total War or Crusader Kings. He's also been known to set up shop in the latest MMO and likes to wind down with an endlessly deep, systemic RPG. These days, when he's not editing, he can usually be found writing features that are 1,000 words too long or talking about his dog.