Our Verdict

Maquette has enough interesting ideas to push any adventure gamer past the finish line.

PC Gamer's got your back

What is it? A first-person puzzle game on a psychedelic scale.

Expect to pay: $20/£15.49

Developer: Grateful Decay

Publisher: Annapurna Interactive

Reviewed on: Windows 10, GeForce GTX 1070, Intel Core i7-9700 CPU, 16GB RAM

Multiplayer: No

Link: Steam

Maquette, the first game from studio Grateful Decay, wants to put an emotional pulse into the staid, first-person puzzler. Classics of the genre—Myst, Riven, The Witness—are heavy on the deceptive, occasionally ingenious tests of perception and reasoning, but unless you are one of the rare souls who pores over D'ni lore, there's little chance you felt any significant investment in those lonely shores, or the stranger that washed up on them. Maquette takes the opposite approach. The setting is still surreal, hallucinogenic, and very Myst-y, but it cloaks all of its strangeness in a very ordinary narrative about two artists in San Francisco who fell in and out of love. There are no shocking twists or aching ambiguities or hair-raising stakes. No, this is a very ordinary, relatable story, the sort of thing that happens every day. That is both Maquette's strength and weakness.

In Maquette, you will move time and space to climb up a set of stairs.

Before we dig into all that, let's talk about Maquette's puzzles. You find yourself deposed on a mystic pagoda, surrounded by steepled castles, haunted woods, and blooming gardens. In the center of the pagoda is a diorama that mirrors the surrounding terrain on a much smaller scale. Everything is reflected and refracted. If I'm carrying a key and drop it in a corner, a much smaller key will appear in the diorama. If I pick up the smaller key and chuck it somewhere else in the diorama, the regular sized key will appear at the same coordinates in the real world. So, in an early puzzle, I picked up my normal-sized key and wedged it in between two pillars within the diorama. Sure enough, as I walked over to that location, I saw that a massive, golden key had fallen from the sky, serving as a makeshift bridge.

Every puzzle in Maquette iterates on that concept: shrinking or expanding the scope of the map with the power of perspective. Nearly all of Maquette's seven chapters are centered around that diorama, and within an hour of playing, the design team will ask you to explore the fringes of what this skewed reality implies. Perhaps you yourself are standing in a diorama, and there might be a much larger diorama encasing whatever you've concluded to be normal-sized. Just food for thought. There is a bombast to some of the Maquette's grander reveals that other games of the same ilk simply can't muster. In The Witness, a sublime eureka moment may occur when you notice a conspicuously placed orange on an unremarkable tree. In Maquette, you will move time and space to climb up a set of stairs.

The diorama, the way I see it, is a pretty transparent metaphor for the inside of a human mind while it's been intoxicated by a love affair. The honeymoon period, in the first few chapters of the game, are arcadian and verdant—scored by nothing more than the sounds of happy, chirping birds. As the cracks in the relationship begin to show, the setting gets muddier, spookier, and more dilapidated. By the end, calamity has struck, and the rebuilding process begins anew.

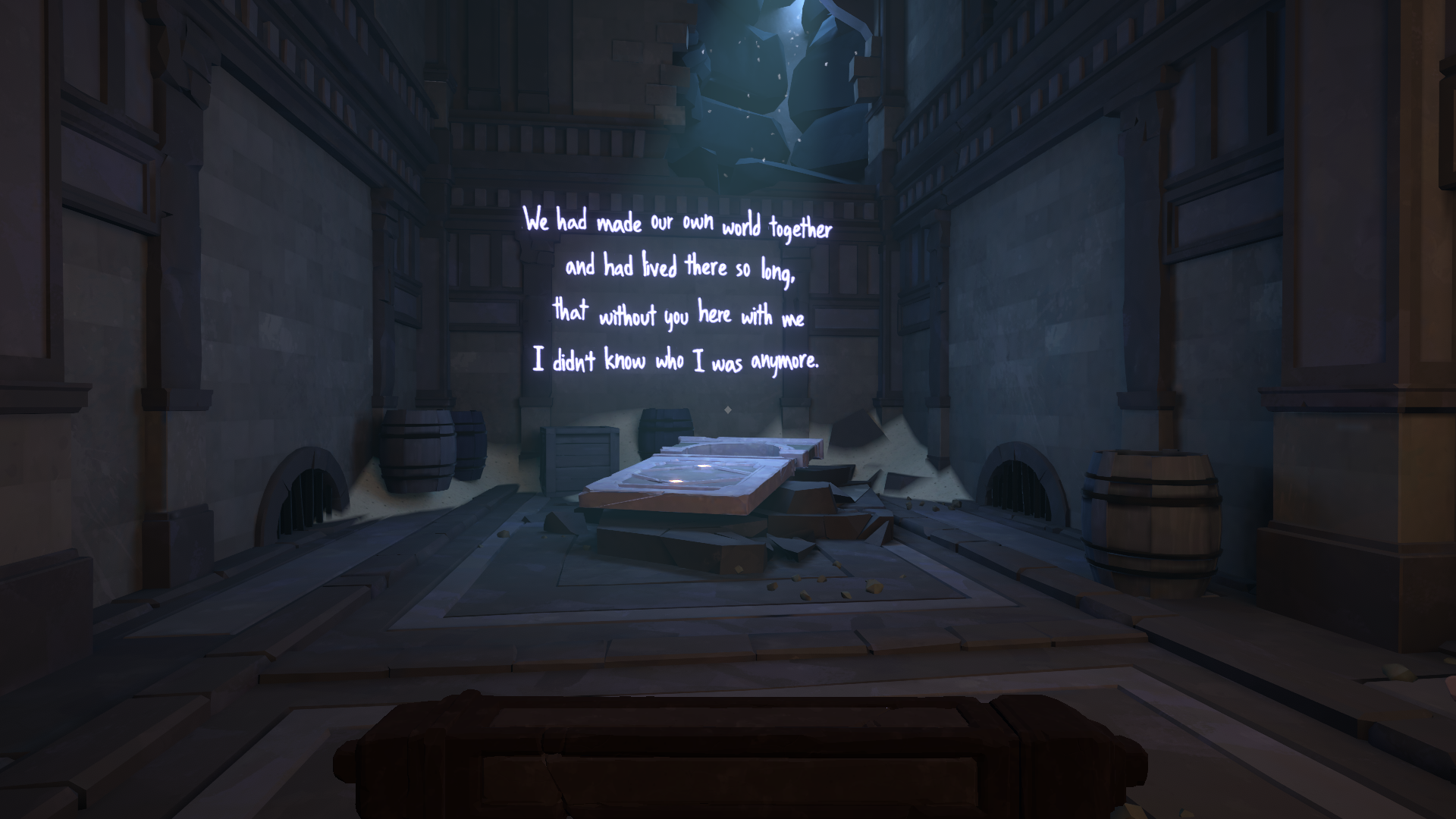

Maquette's story unfolds through a series of wistful stanzas that appear written out in certain niches of the map, and the occasional fully-voiced cutscene where we learn, firsthand, of the saga of Kenzie and Michael. They meet at some coffee shop in the Bay Area, go to a fair, fall in love, move in together, and… well, you know the rest. It's an exceedingly realistic portrayal of modern romance—there aren't any skeletons in the closet, or awkward, pulpy operatics. Two people get together in a very normal way, and then break up in a very normal way, as a result of compatibility issues that will be exceedingly familiar to the general dating populace. In fact, the best scene in the game happens after all the tumult, as the two meet up for one final adieu. It's underwritten in a way that feels very, very true.

We never see Michael or Kenzie face to face—these cutscenes are accompanied with little more than a few drawings—but I never felt lost. Maquette lets you know exactly who these people are, and where they stood, at every point in their journey together. A few treacly passages made me roll my eyes, but from start to finish, I wanted to see where these two ended up.

The galactic proportions Grateful Decay is working with don't mesh well with rote, adventure-game tedium.

That said, it's an intentionally sparse narrative. In fact, throughout the game you won't know if you're playing as Kenzie or Michael (the two even share the same pet name for each other, Sunflower). The universality of the scenario is accentuated as a result, but I couldn't help but wish there was a little more meat on the bones. Michael and Kenzie don't have much to them. Their sole defining quality is that they simply love each other very much, and while that's more than enough to carry a romance, I wish I was offered a better sense of why they clicked in the first place. Obviously, there's not a huge amount of real estate for exposition within the puzzles, but the scant few scraps of meetcute dialogue don't carry enough weight.

I felt the same way about some of the puzzles in the latter half of the game. The playground Grateful Decay has created here—this massive, mind-expanding kaleidoscope of magnification and expansion—never totally cashes in on its psychotropic potential. There is some inspired problem-solving in Maquette, don't get me wrong, but I also found myself trudging back and forth through a barren plain of nothingness to finetune the exact position of a miniature staircase. The galactic proportions Grateful Decay is working with don't mesh well with rote, adventure-game tedium. One or two more psychedelic apexes—like flipping over a Switch controller to solve one of Breath of the Wild's ball-and-maze gauntlets—would've served the game well.

This is underscored by some wonky controls. Simple inputs—like trying to slide a wooden block into place on a grid—are hampered by floaty first-person handling. I was only authentically pissed off at Marquette once during my playthrough, but it feels like a problem that could've been fixed, not something fundamental about the game.

That said, the beauty of Maquette is that it quietly phases out of your life after about three hours. I played the game in a single evening, and sank deep into its thematic grounding. Even in a crisis, when it feels as if your brain has severed its failsafes and is cascading through a bottomless disaster, human beings have a way of finding fertile soil again. That's not a new story, but it's always a good reminder.

Maquette has enough interesting ideas to push any adventure gamer past the finish line.

Luke Winkie is a freelance journalist and contributor to many publications, including PC Gamer, The New York Times, Gawker, Slate, and Mel Magazine. In between bouts of writing about Hearthstone, World of Warcraft and Twitch culture here on PC Gamer, Luke also publishes the newsletter On Posting. As a self-described "chronic poster," Luke has "spent hours deep-scrolling through surreptitious Likes tabs to uncover the root of intra-publication beef and broken down quote-tweet animosity like it’s Super Bowl tape." When he graduated from journalism school, he had no idea how bad it was going to get.