Our Verdict

Gris’s visual appeal hinders as much as it helps its exploration of grief.

PC Gamer's got your back

What is it 2D platforming journey through grief.

Expect to pay $17/£14.49

Developer Nomada Studio

Publisher Devolver Digital

Reviewed on Windows 10, 16GB RAM, Intel Core i7-5820k, GeForce GTX 970

Release date 13 Dec 2018

Multiplayer No

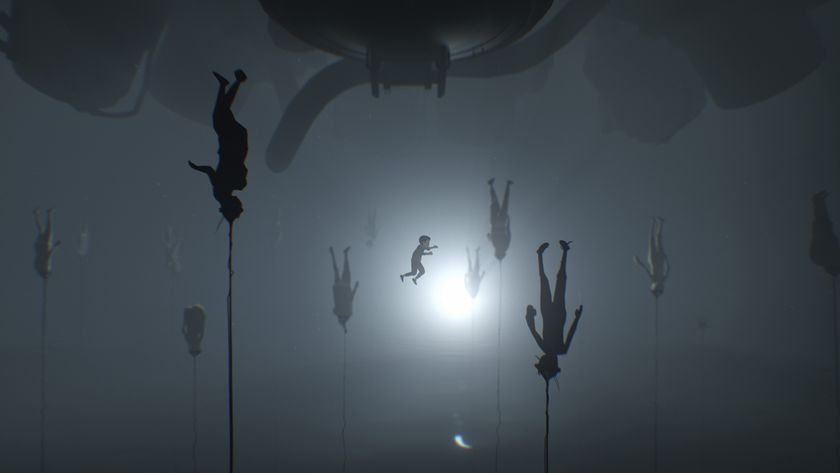

Gris is beautiful. It is beautiful in that highly stylised, minimalist way that works well in both 2D platformers and in art prints. It is beautiful in its carefully chosen colour palettes and its delicate animation effects. But it is beautiful in ways that both strengthen and weaken it as an experience.

Gris is a 2D platforming mood piece about navigating grief. You play as a nimble, blue-haired girl with more than a little of Scott Pilgrim’s Ramona Flowers about her and you must gradually bring colour and life back to a world of monochrome ruins. To do this, the girl must jump, float, swim, and slam her way through stunning environments, collecting glowing lights and adding them to the sky above a hub area as constellations.

Tonally, Gris inhabits the same general area as Journey, Abzu, Unravel, Flower… perhaps Monument Valley too, although not as closely due to the latter’s puzzle elements. Gris isn’t a puzzler, rather it’s a platformer with a set of interactions which feel specifically geared around sensory pleasure—you end up luxuriating in its environments and effects, or enjoying the smoothness of a set of movements.

To give an example, clusters of red butterflies boost your jumps. In another game this boost might feel like part of a toolkit for exploration, but Gris has generally linear progression. This means if you spot a cloud of butterflies you know a butterfly boost is almost certainly the next move in a predetermined route.

At that point, the boost isn’t a tool—you’re not wondering how best to use it—it’s part of the level’s built-in choreography. When it’s at its best, Gris enables you to chain boosts together with other interactions—swimming leaps, floating jumps, heavy thuds—and create a lovely flow and cadence. There are some collectables if you do stray from the path, but finding them tends to mean going against this flow. I picked up a few (particularly in parts where the flow was less clear), but didn’t feel any urge to complete the collection.

As an exploration of grief, or an emotional journey, Gris finds mixed success. Its determination to be beautiful is a significant problem here, because it means the ugly and destructive sides of grief or loss are absent.

The closest you get in terms of what the girl can do is the ability to turn her cloak into a heavy cube, and use it to smash vases, punch through crumbling floors, or plummet deeper into the water. It’s destructive, sure, but it’s also controlled and purposeful.

The wilder, scarier side of grief is cut off from her; cauterised in favour of fluid, deliberate action. It’s perhaps found in some of the strange shadowy creatures which pursue her, but in those moments it’s about the environment acting on the girl; it’s external rather than internal.

The other big problem is that the grief is never effectively localised to a particular person. Is the girl grieving the loss of her companion, or is the companion the one grieving (she seems to be the one shattered into pieces), and the girl is helping her find a way through? Being ambiguous isn’t a problem per se, but I felt unable to read the basic emotional arc as a coherent journey.

This next paragraph is a spoiler (although I’d say Gris’ arc is predictable enough that I wouldn’t find it actually ruined the game) so skip ahead if you’d prefer to be completely in the dark:

Another issue I have is that the ending of the game is positive; a reunification of sorts. I find it to be a significant stumbling block when considering Gris as a representation of grief. It’s too neat—a manifestation of the idea that grief ends when I don’t believe it does. One of the best descriptions of grief I’ve ever heard is about how grief is not a specific feeling, but a reckoning with what can’t be undone. It changes over time, for sure, but it’s an ongoing confrontation, rather than a path to a full resolution.

So Gris is beautiful. It really is. But for me that beauty means it’s only really capable of touching on some of the facets of loss. It offers some of the wordlessness, the colourless strangeness of the world immediately after a loss and the seeping in of colour as you open back up. It also manages some of the sense of being at the mercy of the outside world. The way it plays with scale shifts your focus from the girl to the world and back again, depending on how far the camera has zoomed out; a handy tool for simulating numbness or distance.

But it can’t do the same for rage or guilt or the way your insides seem to be entirely absent sometimes. The beauty gets in the way there. It’s too self-conscious, and too wrapped up in being aesthetically pleasing. It’s too tied to the idea of a neat conclusion. It’s so caught up in the language of recurring motifs and visual continuity that it doesn’t seem to notice when the emotional arc loses clarity and continuity.

The overall effect for me ends up being elegant but detached. A slightly muddled compendium of the picturesque sides of grief.

Gris’s visual appeal hinders as much as it helps its exploration of grief.