Breaking the internet: The story of EverQuest, the MMO that changed everything

How a group of nobodies came together to create the game that defined a genre.

You don't know what success feels like until you've tanked the biggest internet pipeline into San Diego for a week—minimum. Sure, most online games have network issues on day one, but in 1999 EverQuest wasn't just coughing out innocuous error codes. It was so popular that the internet provider hosting its servers had to physically run more cables to Los Angeles just to accommodate the tens of thousands of players dying to explore its cutting-edge 3D world.

"We used it all," laughs John Smedley, one of EverQuest's creators. "All of it. It was the largest internet connection into San Diego and it was constantly going down. It messed up internet here in San Diego for a good solid week."

During that seven-day nightmare, every corporation on that network had their online operations sabotaged by a bunch of nerds who'd somehow been given $4.5 million dollars and a mission to create something extraordinary. And for its time, half a decade before World of Warcraft, EverQuest was nothing if not extraordinary.

Last ditch effort

It was a Saturday morning in February of 1996 when Brad McQuaid picked up the phone. The man on the other end introduced himself as John Smedley, an executive from Sony Interactive Studios America. As 27-year-old McQuaid struggled to comprehend what was happening, Smedley cut straight to the chase: "I have some good news and some bad news."

Many months earlier, McQuaid and his friend Steve Clover had made a desperate attempt to realize a childhood dream. Since he was a kid playing Ultima 2 on his school's Apple IIe, all McQuaid wanted to do was make sprawling, inventive RPGs like Richard Garriott. Two decades and one half-finished university degree later, McQuaid and Clover were spending their days working in IT at a plant nursery before swapping floppy discs at the end of their shift and staying up all night programming a roleplaying game called WarWizard 2. This sequel to their relatively unknown Amiga RPG was their pet project, but with no money to finish development and no publisher offering to fund it, WarWizard 2 was doomed. Out of options and frustrated, they posted their half-complete prototype on the Usenet bulletin boards and hoped someone would take interest.

"The idea was that we'd throw it out there, put a cover letter and an intro to the game, and say that if you have any interest in this call my home number," McQuaid tells me. "Steve was like, it can't hurt. Let's do it."

Weeks went by. Then months. Not a single person called McQuaid about the demo. So you can imagine McQuaid was a little confused when Smedley told him that, despite thinking WarWizard 2 was very impressive, he didn't want to help finish it. That was the bad news, Smedley said. The good news was that he wanted to tackle something much more ambitious.

The biggest gaming news, reviews and hardware deals

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

Humble beginnings

At that time the industry was so small, so I had to find just the right people.

John Smedley

The 1,993rd year of our lord was a different time for the internet. Napster wouldn't piss off Metallica for another seven years, no one found joy in a creepy 3D dancing baby, and the entire metastructure of networks we call the internet was just one of several online services competing to connect corporations and computer nerds. If you've ever looked at your internet bill and grumbled about the extortionate monthly fee, Smedley has a sharp reminder for you: That shit used to be charged by the hour.

Despite how arcane online services were back then, Smedley knew they were the future. In 1993 he started playing CyberStrike, a primitive 16-player mech game that was in the vanguard of 3D multiplayer gaming. "It got me hooked on online games in a big way," Smedley says. Though CyberStrike cost an eye-watering six dollars an hour to play, the idea that 16 people from across the world could compete in a virtual arena was revolutionary. Computer Gaming World awarded its first-ever "On-line Game of the Year" award to CyberStrike. Three years and many painful billing cycles later, Smedley was working at Sony Interactive Studios America (SISA) making sports games for the PlayStation. But he really wanted to make an online game like CyberStrike.

Unbelievably, SISA executives bought into Smedley's dream and gave him a few million dollars and their blessing to start a PC development team in a company dominated by console games and college sports fanatics. "So I went out into the shareware world looking for people who were fairly close by," Smedley says. "At that time the industry was so small, so I had to find just the right people."

The right people, it turns out, were Brad McQuaid and Steve Clover. "When I found Brad and Steve's demo online and contacted him, we immediately meshed well and he had a great creative vision," Smedley tells me. "The only thing was that Brad didn't know how to make a professional videogame, but I had that experience."

McQuaid jokes and says he didn't have the money to play the graphical online games that Smedley loved, but he and Clover saw the future in a very different kind of multiplayer game. Called MUDs (Multi-User Dungeons), what these text-based multiplayer roleplaying games lacked in fancy graphics they made up for in depth and scale. Similar to traditional pen and paper roleplaying games, players could socialize and explore virtual fantasy worlds together—only everything was described through text. "They were mostly played by kids in colleges who could telnet into the college mainframe or minicomputer. I don't know how they didn't get kicked out of school because they were just playing nonstop," McQuaid says.

When Smedley said he wanted this game to be cutting edge, McQuaid saw an opportunity to do something completely unheard of: A MUD with 3D graphics. Two days after that phone call, he and Clover resigned from their IT jobs and joined SISA. "It was an opportunity we could not pass up," McQuaid says. "It was an amazing, life-changing day for sure. I felt absolute excitement."

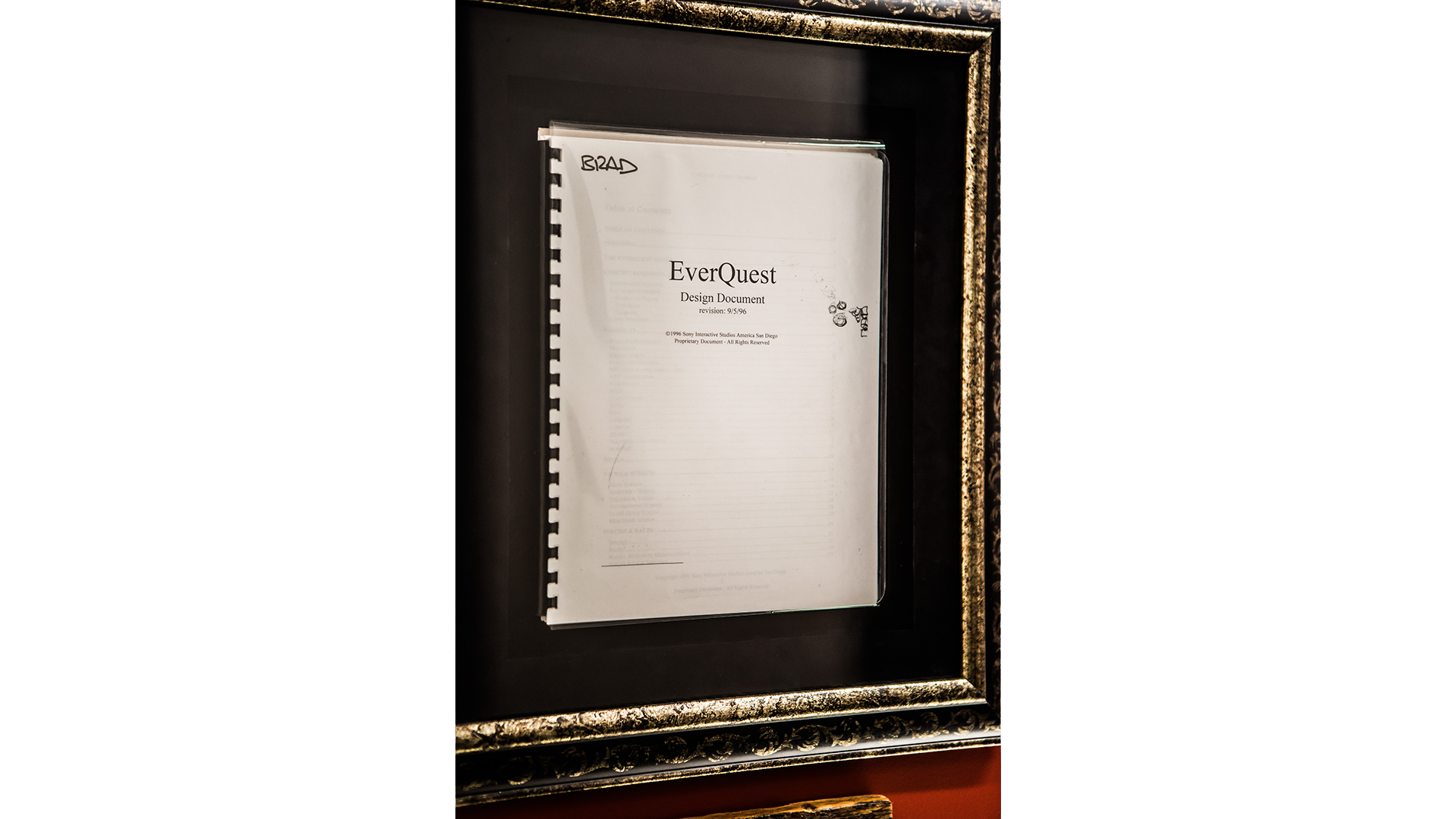

What McQuaid lacked in professional game development experience, he made up for in project management knowhow, extensive programming skills, and raw creative vision. The two dreamed up an outline for a graphical MUD and created a 20-page design document to act as their bible. In that document, McQuaid and Clover cemented the foundation of its systems, like class-based combat, an emphasis on player-versus-environment exploration, and the basic layout of a high-fantasy world that became known as Norrath. Clover gave it a name: EverQuest.

Loser's club

They laughed at us and said we were crazy.

John Smedley

McQuaid and Clover were a good start, but they couldn't build an entire 3D game on their own. As months ticked by and development on EverQuest scaled up, it was becoming increasingly obvious that no one outside of the development team had any faith in Smedley and McQuaid. "We reached out to people in the industry at that time who were working on these pay-by-the-hour type games," McQuaid says. "We wanted to bring those people in because they were the veterans of the day—they had the most commercial online experience. They laughed at us and said we were crazy."

It wasn't just that EverQuest wanted to be an multiplayer roleplaying game. There were dozens of those. And it wasn't that EverQuest would sport state-of-the-art graphics. It was that McQuaid wanted to combine the two in a massive open world that thousands of players could populate at any one time and charge a monthly fee for it. "John was convinced that it was obvious that these pay-by-the-hour games were limited because you had to have a lot of money to play those, but we couldn't make it free like a MUD so that's where the subscription model came up," McQuaid says. "People thought that was a crazy idea."

With no veterans taking them seriously, McQuaid posted job openings at nearby colleges. One of the level designers was a pizza delivery guy who got the job based on enthusiasm alone.

Wanting to repay a favor to two amateur artists who helped him with WarWizard 2, McQuaid phoned up Bill Trost and Kevin Burns. Because they had no real background in professional art, the pair joined at Sony as testers to get their foot in the door and worked after hours designing mockups and art assets before Smedley was able to bring them on full-time. Meanwhile, Rosie Rappaport, an artist, worked in the same 'bullpen' as McQuaid and the team, and once she found out what they were doing she asked to join the project. Trost and Rappaport would become key ingredients in EverQuest's success.

Most of the people at Sony were just as skeptical as the industry veterans Smedley tried to recruit. Rappaport says other developers at SISA took to calling the game "NeverQuest," while Smedley adds that the team was mockingly referred to as the "Ghouls and Goblins Guys" when they'd gather to play Magic: The Gathering in the lunchroom. "This was a studio that was filled with sports people," Smedley laughs. "And then this small group of us that was into Dungeons and Dragons."

EverQuest was so audacious, even Smedley's boss was a little embarrassed by it. Sony, like many Japanese tech companies with American branches, was a hydra with heads prone to biting each other on a whim. Smedley's hardest challenge was keeping EverQuest away from the jagged teeth of upper management. "My boss at the time, a guy named Kelly Flock, he didn't even want to admit that he was doing this game to the Japanese management team who had no idea we were making this PC game," Smedley laughs. "It was kept very quiet."

"I was having to protect the development of EverQuest and it was pretty difficult," Smedley adds. "They actively laughed at it and thought we were wasting money. In meetings I was constantly having to justify why we were doing it."

That's how EverQuest first came to life, in the bullpen of a PlayStation studio where everyone was either ignorant of its existence or convinced that the bizarre high-fantasy RPG would fail. As Smedley would later realize, it was the perfect place.

Origin story

EverQuest's development team had absolutely no idea how to build a massively multiplayer online game, which sounds like a bad thing. It turned out the opposite was true. "We had no idea of what could or couldn't be done," McQuaid says. "That was the key, though. We didn't have any veterans in there that said no you can't do that, that's too ambitious. We were like, this is what we're going to create, and we're going to go for it, and we're going to make it work, and we're going to keep trying until it all comes together."

As development ramped up, the team also expanded and the initial members were all promoted. McQuaid became EverQuest's producer, Clover its lead programmer, Rappaport its art director, and Trost its lead designer. Their first mission was to build a working prototype of a multiplayer dungeon for a party to run around in. As EverQuest was coming to life in a technical sense, Bill Trost was bringing it to life in a very different way.

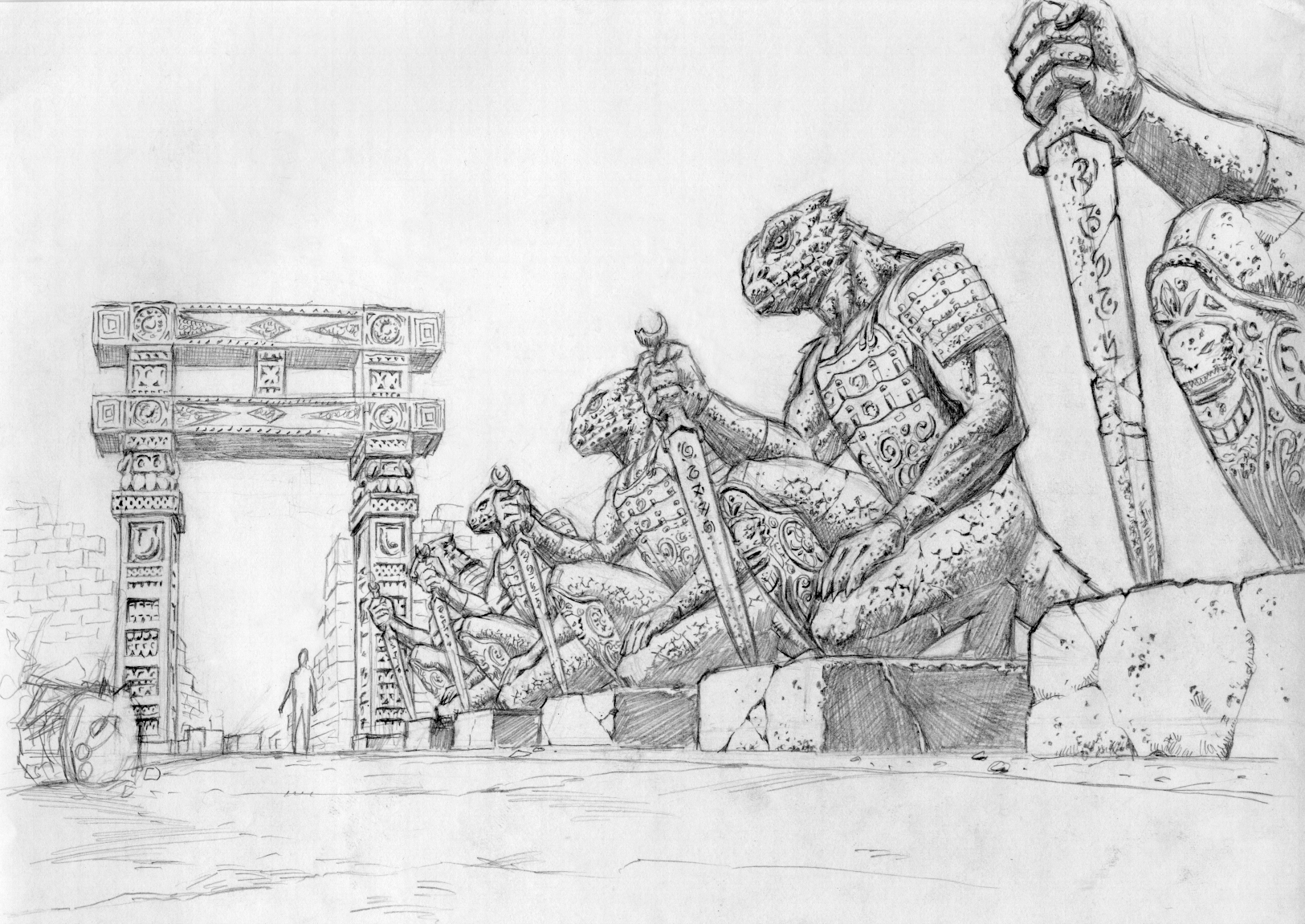

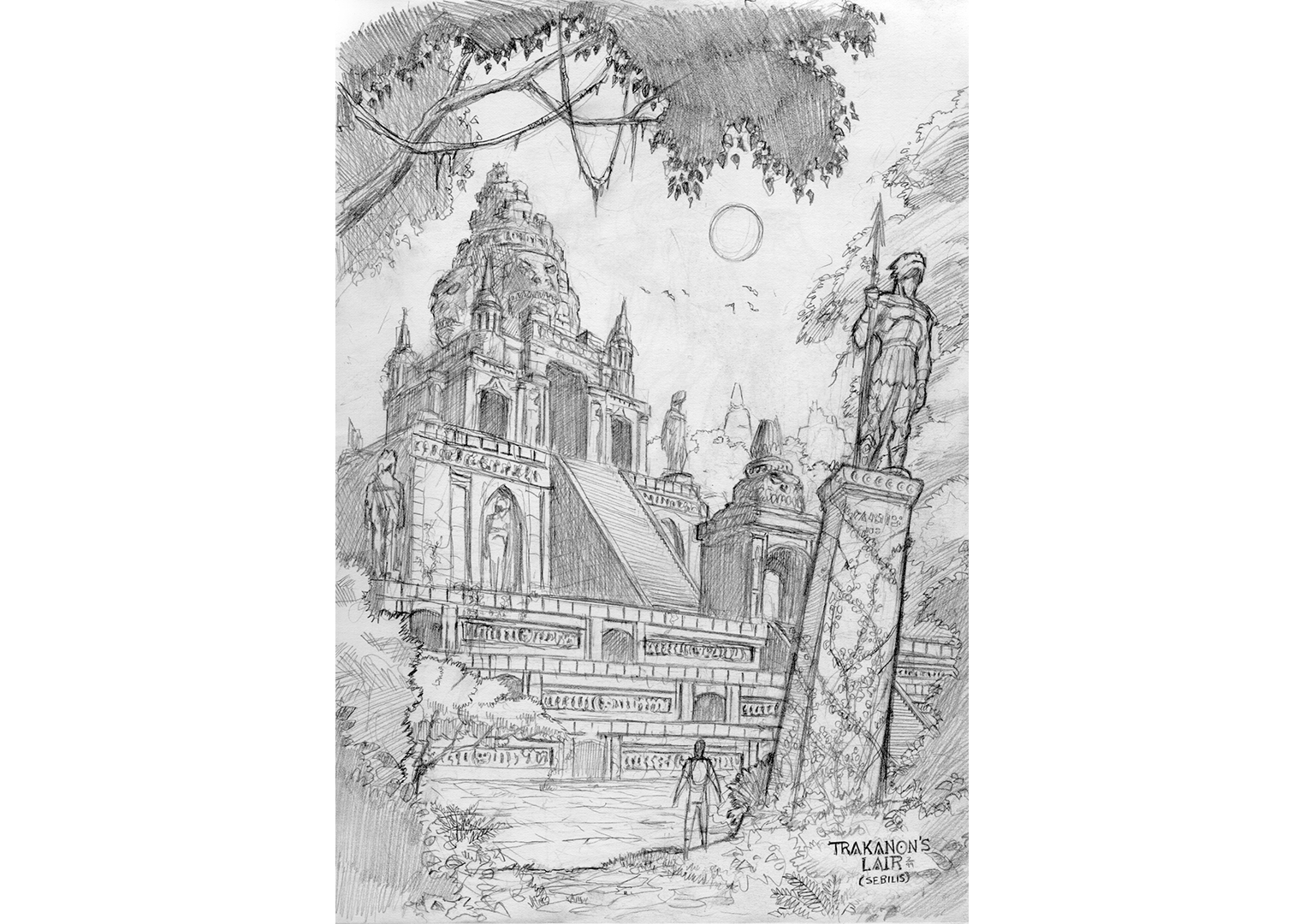

Like most of the team, Trost had grown up going on imaginary adventures with his friends in Dungeons and Dragons. But Trost was a natural-born dungeon master. He lived to create worlds—and the rough narrative outline detailed in EverQuest's 20-page design bible wasn't going to cut it. "No one had articulated there was a need for EverQuest to have a lot of lore," Trost laughs. "It was just something that, coming into it as a dungeon master, I was like, ugh, if we're going to have people play this game we need to figure all this stuff out."

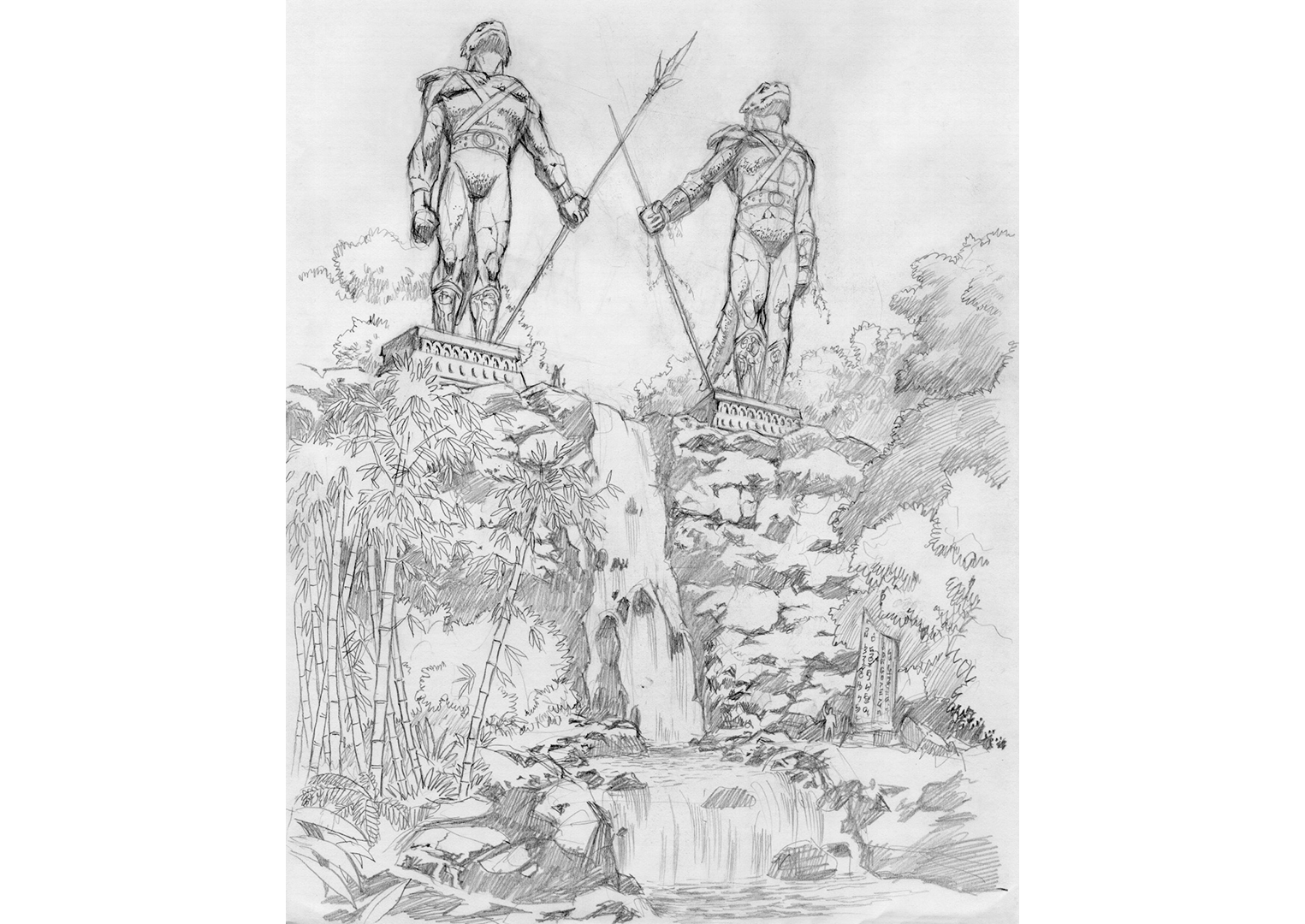

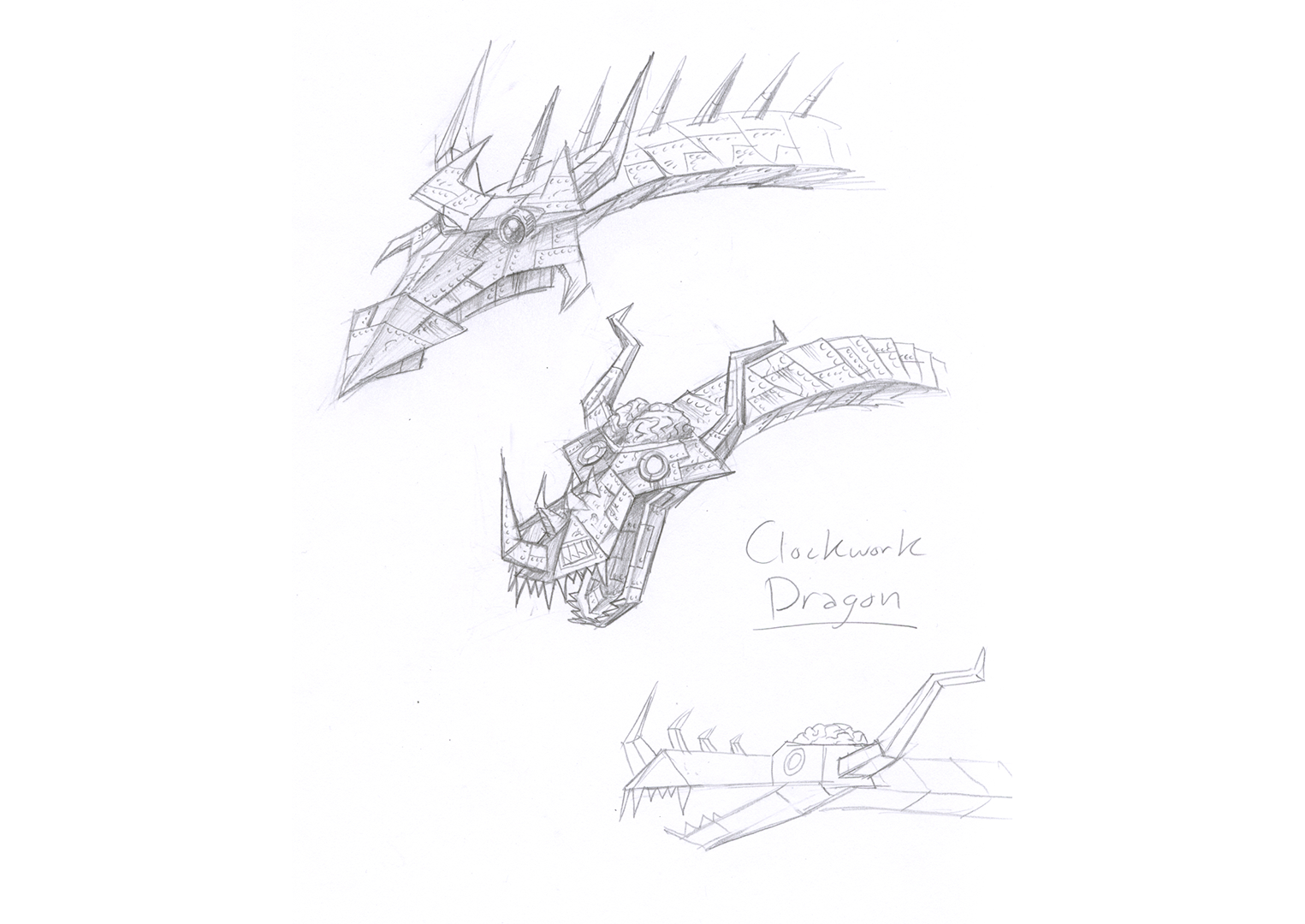

McQuaid and Clover had mapped out a rough sketch of EverQuest's continents and the various races who resided there. Trost took those seeds and cultivated a garden. When he wasn't building art assets or helping design the user interface, he was dreaming up Norrath's pantheon of deities, penning the histories of its people, and molding a vast army of non-player characters that would populate the world. But much of the work had already been done.

"A lot of what became the world of Norrath and Everquest, I used from my Dungeons and Dragons campaign as a kid," Trost says. That included famous EverQuest characters like Mayong Mistmoore, a conniving spymaster and elf who would become Norrath's first vampire. He was actually Trost's primary D&D character.

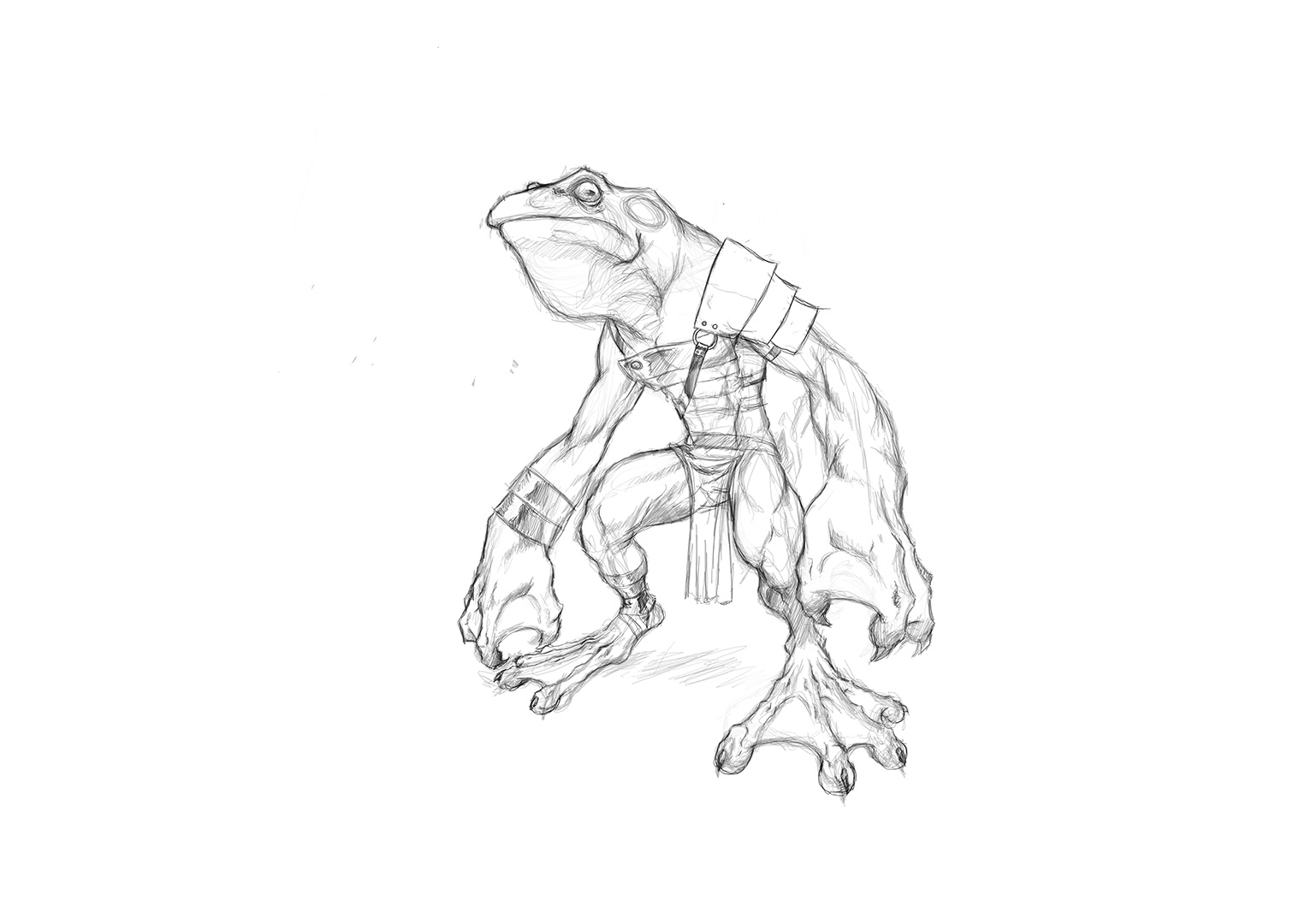

Meanwhile, Rappaport was bringing EverQuest's aesthetic to life in much the same way. "The high fantasy at the time was coming from different book covers or from Frank Frazetta, who was everybody's hero," Rappaport says. "But I really wanted something more whimsical and lighthearted for a lot of the characters. We talked about making the really ugly characters have more comedy to them, like the goblins having a visible buttcrack that they'd itch."

"I didn't want anything to be grey because at the time roleplaying games were brown and grey, everything was wood and stone," she adds. "I wanted everything to have more colour and personality, because colour is another voice that creates a story."

Though not everyone liked that light-hearted aesthetic, Trost also wasn't a fan of overly serious fantasy. The two worked closely to dream up quirky twists on fantasy staples and pulled inspiration from the most unlikely of sources. Like any true Californian, Rappaport and Trost were fans of alt rock band Blind Melon. After seeing their music video for "No Rain," in which a little girl prances around in a bee costume, they had the idea for one of EverQuest's most iconic creatures, the Bixie—one part bumble bee and one part mischievous pixie. "That was just Bill and I shooting the shit and wanting to create colorful creatures that would make the world more fun and interesting," Rappaport laughs.

If that underlying tech wasn't there, there would be no EverQuest,

Brad McQuaid

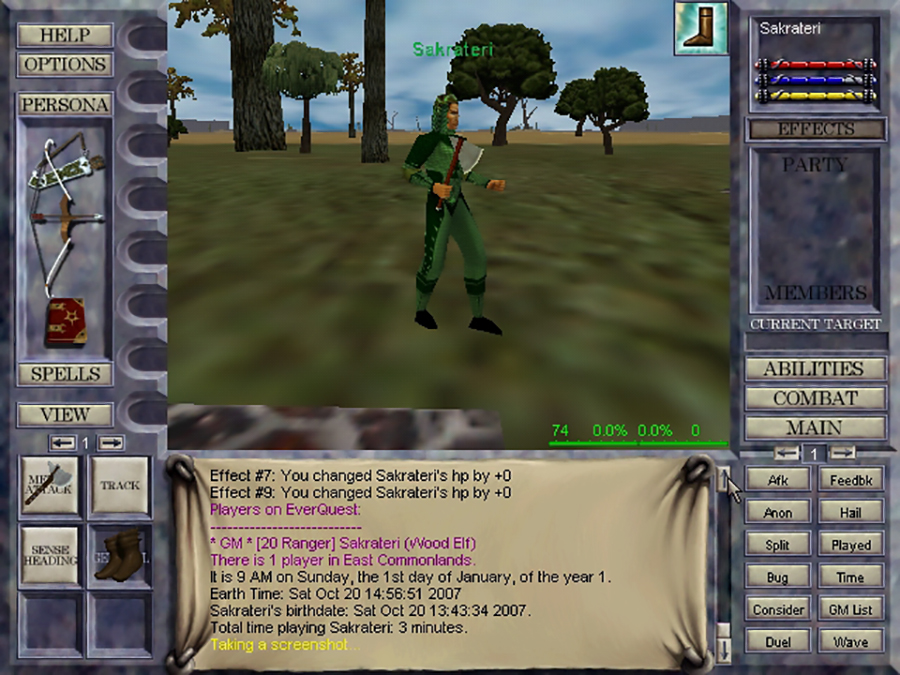

McQuaid, Clover and the rest of EverQuest's programmers were tackling very different kinds of problems. EverQuest wasn't just ambitious in its use of groundbreaking 3D technology, but also the scope of its world and combat. McQuaid envisioned 14 classes and 12 races that players could combine to create their avatar—everything from half-elf druids to ogre shadowknights. But the real challenge was getting all of that information to transfer across the slow-as-hell 28.8 kbit/s modems that most people used. "If that underlying tech wasn't there, there would be no EverQuest," McQuaid says. Thankfully, there was Vince Harron.

There are two common protocols for communicating on the internet: TCP/IP and UDP. Though complicated, the gist is that the former is slow but stable and will send packets of information with delivery confirmation notices. If a packet goes missing, TCP/IP will send a new one. UDP is much faster but couldn't care less if packets arrived at their destination. "Vince, who is a brilliant programmer, came in and wrote what we ended up calling Reliable UDP," McQuaid says.

It was a protocol that let EverQuest determine when to send reliable or unreliable data. "When you're running around and you're updating the server with your character's location," McQuaid explains, "that was usually sent unreliably because if there was a lost packet it was no big deal. Those packets were being sent out often because everyone is constantly running around. But if it was something like trading an item, we sent that reliably."

"That was a critical piece of technology that most people aren't even aware of," McQuaid says. "And Vince is an unsung hero because he was down there in the trenches working on this network code."

No faith

All throughout its development, Smedley was working to keep EverQuest a secret. "It was exactly the right incubator," Smedley says. "There was a lack of attention focused on us, but that same lack of attention gave us creative room to breathe life into what would become EverQuest. There was not a shred of interest from one executive period. Not one of them looked at it a single time."

Over two years passed while EverQuest's team of roughly two dozen developers worked day and night to make their dream come true. When Trost says that people were sleeping under their desks at night, I mistake it for hyperbole. But then Rappaport says the same thing. "That was the hardest that I've worked on any game," she admits. "There was a ton of overtime, and we were just always there and sleeping under our desks and going home at 2 AM night after night. I remember one time I took a Saturday off and I was like oh, this is what weekends are. I had forgotten."

"It was a culture of do or die," she says. "There was nobody on the team that was just doing it halfway. Everybody was a hundred and ten percent all the time, every last person."

McQuaid says it took almost two years before he started to think that EverQuest might actually work. "We knew that these MUDs were extremely compelling," he says. "But the big question was whether we were just a strange microcosm of people that like this kind of game or is this something that could be commercially viable."

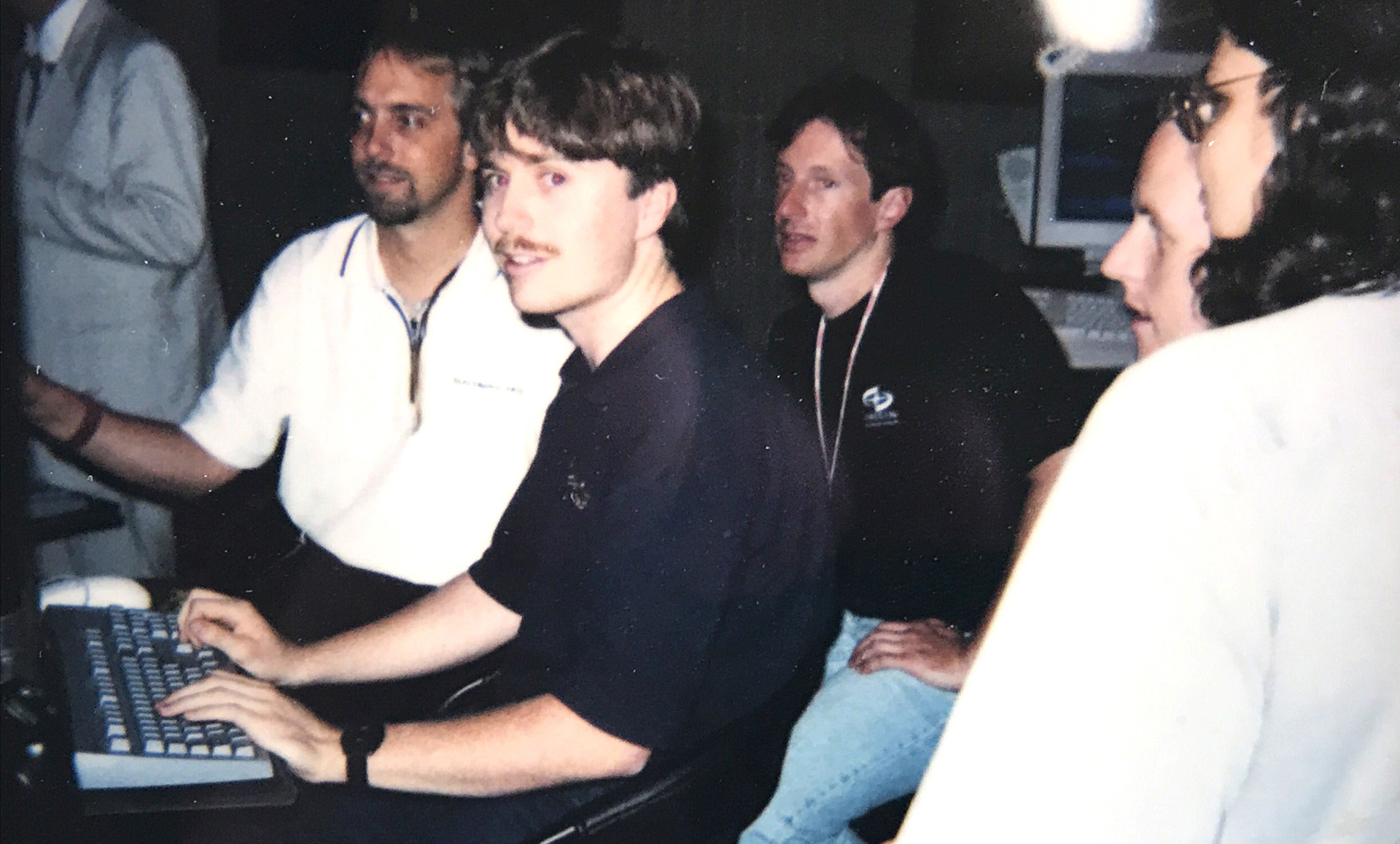

It was at the Game Developers Conference in Long Beach, California that McQuaid finally realized EverQuest might be successful. It was the spring of 1998 and the EverQuest team was there to demo the fledgling MMO in hopes of getting some valuable feedback. "We set up eight or ten computers in two rows and we allowed people to come up and create a level one character and just run around, figure out the game, kill stuff, and talk to people."

To give everyone a chance, players could play for just 20 minutes before they'd have to log out and let someone else try. But "a lot of them would leave one computer and sneak around to the other side and log into their account and continue playing their character," McQuaid noticed. "We had to constantly police and pull people away from EverQuest so that other people could experience it. And some people even got a little belligerent. When you're prying people away from your own game that you're trying to demo, that's a good sign."

Richard Garriott's groundbreaking MMO, Ultima Online, had also launched a year earlier and proven that online RPGs with monthly subscriptions could be profitable. Interest in online gaming was surging as EverQuest inched closer to release.

And then Sony's upper management found out about Smedley's little secret.

With the constant mergers and restructuring of Sony's various corporate divisions in the late '90s, it was more like a barbarian horde than a Roman legion—a loose assemblage of tribes that, more often than not, devoured each other.

What you need to know is that at some point, Sony Interactive Studios of America became 989 Studios and then, some time after, shifted focus towards developing PlayStation 2 games in anticipation of the console's launch. For over two years, Smedley had been running interference and doing his best to keep EverQuest a secret. Somewhere in that corporate shuffle, Smedley's passion project was discovered by Japanese upper management.

During Everquest's development, McQuaid had the surreal opportunity meet his hero and inspiration, Richard Garriott, and show him the game. McQuaid has a picture that he still keeps nearby. "That was just an amazing moment, sitting down with him," McQuaid says. "He's the nicest guy in the world too. He checked out EverQuest and played it for a while and was asking questions. It was a mindblowing day. I can check that off my bucket list."

Today, years later, McQuaid and Garriott are good friends.

That was when Kelly Flock, Smedley's boss, gave him his own dose of good news and bad news. "Kelly just didn't have the backing from Tokyo to launch a PC business," Smedley explains. "But he did have the backing to let us go out and look for corporate suitors."

It was a bittersweet moment. Sony had put enough money into EverQuest that they didn't want to can the project, but they weren't going to continue feeding it, either. Despite trying to hide it from his own bosses, Flock believed that EverQuest had potential, so he had arranged a deal: Smedley and his team could continue to work on EverQuest as a partially-independent studio, but they would need to find another corporate investor to split the bill.

Though a Microsoft offer was on the table ready to be signed, Smedley ultimately found a corporate suitor in a different Sony company called Sony Online Entertainment. The EverQuest team formed their own company, called Verant Interactive, and moved to a different office building just a short walk away. It was a close call—not that anyone on the development team knew it. "After EverQuest had shipped, John told me that it was almost cancelled five or six times," McQuaid says. "He never told me at the time and I'm glad he didn't."

"I knew that something was happening," Rappaport says. "We were getting new business cards, but I just rolled my eyes and thought it was something for the executives to deal with."

Ignorant of the bureaucracy that almost killed it, EverQuest's team thundered along toward its official release in March of 1999 relatively unscathed. Unable to match their initial scope for Norrath, continents and a few features were trimmed from the original release, but EverQuest was a near-perfect manifestation of McQuaid's and Clover's original vision. "Almost everything in that original design doc made its way into the game," Smedley boasts. "It was very impressive. I'm almost 30 years into this business and I haven't seen that another time, ever."

Launch day woes

EverQuest sold 10,000 on its first day. No one was prepared.

After running the gauntlet for three years together, no one at Verant Interactive had any doubt that EverQuest wouldn't be good. What they never expected, though, was how successful it would be. At the time, only Ultima Online offered insight into the new world of commercial online RPGs. By the time EverQuest launched, Ultima Online had shattered expectations and sold 120,000 copies. But EverQuest was a cutting-edge game that required a computer with a 3D graphics card, a somewhat novel piece of hardware in 1999. The team would be excited if it sold even a quarter as many copies.

Instead, EverQuest sold 10,000 on its first day. No one was prepared.

Andrew Sites, an assistant producer, remembers getting phone calls from friends telling him that EverQuest players were lined up out the door at retailers hoping to buy a copy. That was his first clue that EverQuest's servers were about to be destroyed by a flood of eager players. "You have to understand things were way different to how this stuff works now, where we have all these fancy administration tools and everything," Sites says. "At the time, we had a datacenter and all the servers were like desktop PCs and they were in these racks, and we had to cram as many as we could in there because you had to pay for more space. We found if you pulled the little rubber feet off the bottom you could squeeze in one more row of PCs, which were the EverQuest worlds at the time. There was no remote administration hardware. It was literally 144 serial cables to each of the worlds connected to one PC with a switch box and a monitor."

When EverQuest's servers first went live, they quickly crashed. To keep EverQuest online, three employees would sit in that freezing cold network room wearing parkas and manually reboot the servers. "Keeping that game up when you didn't know what you were doing, which we didn't, was very hard," Smedley says. "Back then there was no one with launch experience. We were just making it up as we went along."

Few, if anyone, could reliably play EverQuest that day. Smedley, Sites, and the networking team were left scratching their heads until they finally discovered the source of the problem. "One of our network programmers had done his math wrong and it meant we were using eight times more bandwidth than we thought we were," Smedley laughs.

EverQuest was using a network managed by a local service provider called UUnet, also used by several major San Diego corporations. But demand for EverQuest was so much greater than Verant Interactive had planned for that it was exceeding the physical limits of the internet pipeline into San Diego. As a result, not only could thousands of players not explore Norrath, several massive corporations had their networking operations accidentally sabotaged. "Once you go over the limit, it basically boots everyone off the network," Sites explains.

Days ticked by as Smedley and crew desperately tried to assuage the growing frustrations of their players and negotiate for better internet access, but UUnet would have to physically lay more cable between San Diego and Los Angeles first. That would take weeks. Meanwhile, a rotating team of three parka-wearing employees took eight hour shifts rebooting crashed servers for days on end.

Fortunately, UUnet was able to reroute traffic and free up bandwidth as an interim solution while they expanded their physical pipeline, and players were finally reliably able to explore Norrath for the first time.

Despite how painful that initial week was, people quickly forgot. EverQuest was revolutionary. By April, EverQuest had sold 60,000 copies. Six months later: 225,000 copies, doubling Ultima Online's already record-breaking numbers in half the time. Though brutally punishing and complex, EverQuest's blend of whimsical fantasy, grueling adventure, and gorgeous graphics encouraged players to bond and form online relationships that became more engaging than its tedious grind. "We created this vehicle for people to come together," Rappaport says. "But the community really created the game themselves. They are the ones that made it what it was."

"I think part of it is just being in the right place at the right time, but I also think that Brad really tapped into such a pure Dungeons and Dragons-style experience that it really resonated," Smedley says.

Overnight, McQuaid and his team became celebrities not just to their fans but in the gaming industry at large. At its height in 2004, EverQuest had sold over 3 million copies and had released a whopping eight expansions (another 17 would follow in the decades after). Blizzard Entertainment President J. Allen Brack would later admit that "[World of Warcraft] took a lot of great ideas from EverQuest" and that "EverQuest is the big foundation for WoW." And even MMOs released today still follow the blueprints of class and world design that EverQuest canonized.

Sony, quickly realizing that EverQuest wasn't doomed, re-acquired Verant Interactive and merged it with Sony Online Entertainment, forming an entirely new PC games division under Smedley's rule. It was a triumphant moment for the "Ghouls and Goblins Guys," but there's no hard feelings about it. "I have to give Sony credit," McQuaid says. "They never really threw us to the curb. They paid for half the funding of the game, even if they were always hedging their bet. It was definitely vindicating, but when I think back, if it wasn't for Sony and the different executives there at the time, and John running interference and protecting the game, then there wouldn't have been an EverQuest."

But back then, no one was really thinking about it. Sure, they had achieved what seemed impossible, but Bill Trost and the other developers had pages filled with notes of new continents and stories that didn't make it into the initial launch to think about instead. There was always more work to do. "We didn't take a lot of time to dwell on it," Trost laughs. "We just divvied up resources and started working on the expansion."

With over 7 years of experience with in-depth feature reporting, Steven's mission is to chronicle the fascinating ways that games intersect our lives. Whether it's colossal in-game wars in an MMO, or long-haul truckers who turn to games to protect them from the loneliness of the open road, Steven tries to unearth PC gaming's greatest untold stories. His love of PC gaming started extremely early. Without money to spend, he spent an entire day watching the progress bar on a 25mb download of the Heroes of Might and Magic 2 demo that he then played for at least a hundred hours. It was a good demo.