Among Us works because it's a board game in disguise

Players make the rules in the social Twitch sensation, not distant designers.

There are three places where you can expect to be shushed by strangers: in a public library, on a quiet train carriage, and during a game of Among Us. All three share a social contract, a communal understanding that this will work better for all of us if we shut up. It’s self-enforced, and I think it’s sort of beautiful.

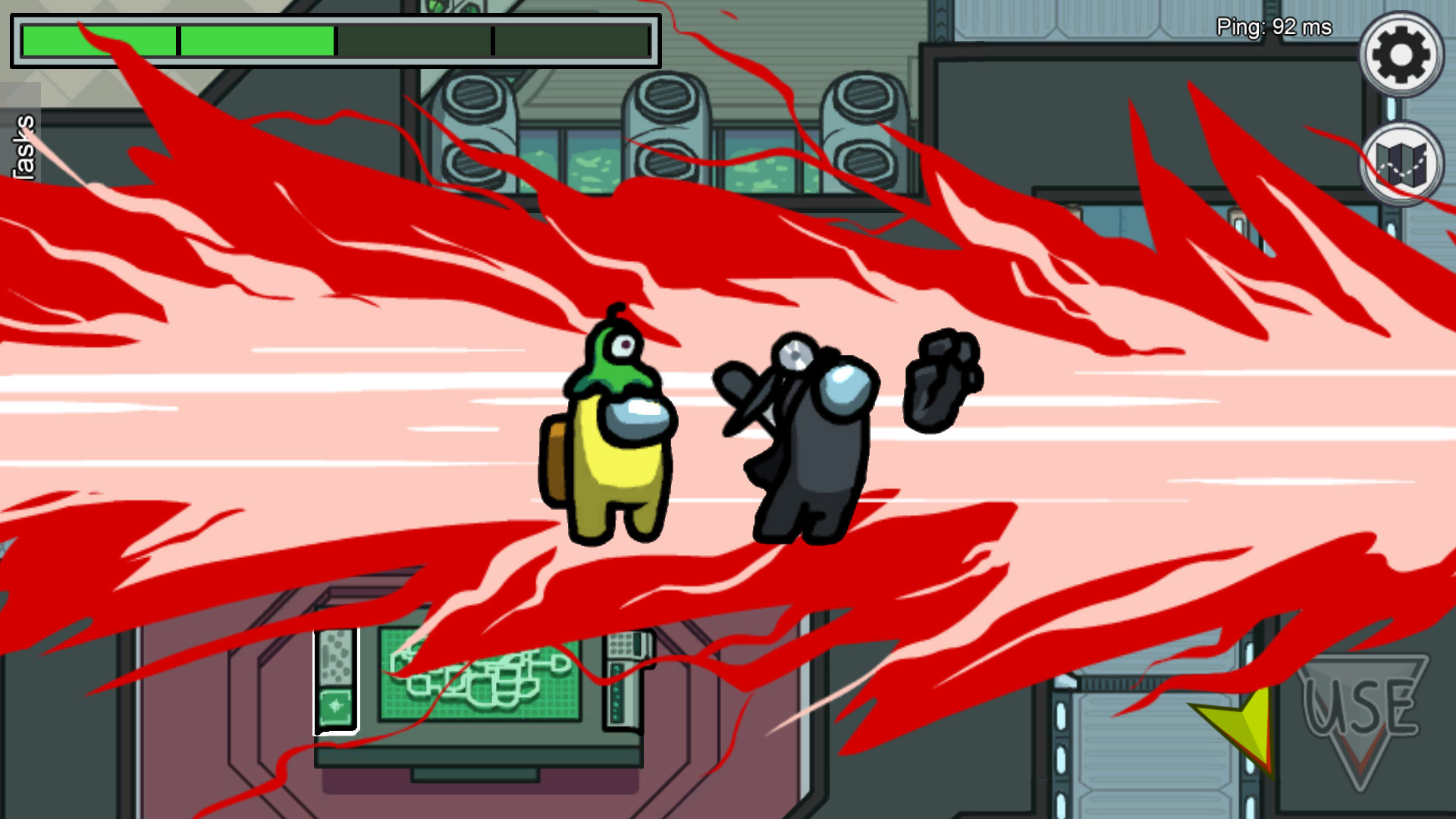

In Among Us, four to ten players go about their maintenance tasks on a maze-like spaceship in complete silence. The quiet is only broken when an emergency meeting is called—either to report a discovered body, or discuss general suspicions about which of their number might be an imposter, chomping off player heads and leaving only cartoon bones behind.

Once that summit is over, and votes taken on who, if anyone, should be ejected from the airlock, the quiet resumes—doubly so for the dead, who are expected not only to keep shtum during meetings, but to stay zipped at the moment of their own surprise killing. That’s a big ask in a mics-on horror game. I fully admit to a giveaway gasp the first time I saw a friend’s tongue dart right through my cerebral cortex.

It’s not an unprecedented premise—station survival sims like Space Station 13 and Barotrauma have long given players secret missions to kill each other, and the imposter role is common to board games. But the system of agreed-upon silence is in stark contrast to the classic PC experience—our rules tend to be hard, unyielding, and defined by code.

In the earliest days of digital gaming, the primary advantage of the computer was its titular function: computation. D&D nerds soon realised that machines could add up dice rolls, apply modifiers for armour, and pump out a damage number far quicker than any human. That potential for instantaneous maths enabled the invention of the action-RPG and beyond. The whole sell of Destiny 2 is that its D&D-like ruleset plays out at the speed of a shooter, and you’re never left waiting for the former to catch up with the latter.

There was another benefit, too: computers were fair in their adjudication. They saw every action and treated players equally, which paved the way for lightning-fast competitive shooters. Today, gaming tournaments are largely free of the referee disputes that plague conventional sports (though we find plenty of ways to create drama of our own).

Gaming’s new dependence on machines came with downsides, however. Not in the Skynet sense, but something subtler—a slow and pervasive rewriting of our relationship with game rules.

The biggest gaming news, reviews and hardware deals

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

The Ubisoft-published version of Monopoly is a fascinating case in point. In theory it allows you to play the eternal tycoon game online, with family or friends who for geographical or pandemic-related reasons can no longer gather in the lounge on a rainy Sunday afternoon. In reality, almost every family that plays Monopoly has its own interpretation of its rules.

Mine, for instance, rejected hotels and mortgaging out of hand, in unspoken agreement that it sounded all too much like work for children and lightly sozzled parents at Christmas. Others have decided that mums get out of jail free, every time, because they’ve done their time already. Another favourite is to award a cash sum for rolling double ones—a lovely conciliatory gesture that keeps the unlucky engaged.

Since the rules are determined by players, they can be reinterpreted to keep the game fresh.

D&D, the game at the very root of PC gaming, has a long and proud history of house rules as well. Its first edition assumed you had the wargame Chainmail to refer to for measurements and combat. And hilariously, it demanded you refer to a wilderness skills board game named Outdoor Survival, which belonged to Avalon Hill, not D&D publisher TSR. As such, players without access to Gary Gygax’s gaming cupboard simply filled in the missing pages with their own rules.

A digital version of Monopoly or D&D closes that off from players—enshrining the rules and ensuring blanket adherence. That’s a recipe for frustration: when the rules in a PC game feel stupid, there’s usually little to do but bang your head against them or vent on Reddit.

The decline in private servers only limits player invention further: where once first-person shooters were home to hundreds of bizarre variations on their primary theme, enabled by strange host settings and mods, they’re now typically played only in the way their creators intended.

Among Us is different. Thanks to the light touch design of developer InnerSloth, there’s been space for players to define a ruleset by consensus. That ownership creates a sense of group investment, as if you’re summoning the game between you—like teenagers around a Ouija board—rather than simply logging onto a platform.

Now that Among Us has reached a critical mass of popularity, some are beginning to tire of seeing the same situations unfold in Twitch streams. But that’s OK: since the rules are determined by players, they can be reinterpreted to keep the game fresh. Streamer Ludwig Ahgren has begun playing the game in ‘Colour Mode’—an ingenious modification in which every player is named after a colour that doesn’t match their avatar, leading to brain gymnastics and misidentification during emergency meetings.

Even if you never fiddle with the established rules of Among Us, there’s a feeling that you’re participating in a true party game—one that couldn’t exist independently of the people who gathered together to make it happen.

Gary Gygax ultimately folded common house rules from early D&D into the official game with Advanced Dungeons & Dragons. And, much later, Hasbro polled Facebook users to find out their favourite house rules for Monopoly, publishing a special edition that codified the most popular—ironically robbing them of their true house rule status.

Some designers will always try to set their games in stone—fearful they might lose control, or ignorant of the joy players get from owning their own experience. But with Among Us, the rules still feel social and malleable. It wouldn’t hurt to have more of that in PC games.

Jeremy Peel is an award-nominated freelance journalist who has been writing and editing for PC Gamer over the past several years. His greatest success during that period was a pandemic article called "Every type of Fall Guy, classified", which kept the lights on at PCG for at least a week. He’s rested on his laurels ever since, indulging his love for ultra-deep, story-driven simulations by submitting monthly interviews with the designers behind Fallout, Dishonored and Deus Ex. He's also written columns on the likes of Jalopy, the ramshackle car game. You can find him on Patreon as The Peel Perspective.