Tom Marks wants the public to think of gaming as more than just Assassin's Creed and Call of Duty.

Chris Livingston doesn't love annual AAA games, but lots of people do. And who is he to say they're wrong? Just look at him.

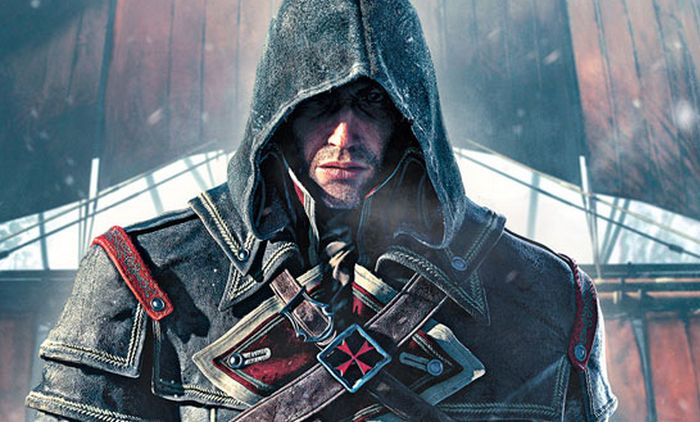

Tom: YES, it oversaturates the gaming market with unfinished and unoriginal games, warping the perception of gaming as a whole. When you make games for a deadline, the games don’t get finished. Plain and simple. It’s the reason I don’t usually mind when a game is delayed, because the developer has recognized they need more time to finish it. But annual or biennial releases restrict a dev’s ability to rethink the amount of time they need. Now, a game being unfinished on launch doesn’t hurt gaming on its own, but these games are the ones being heavily marketed and inevitably seen and played by the average joe—not just gamers. Madden, Call of Duty, and Assassin’s Creed now represent all of gaming to the mass market, and I wish it was represented better.

Chris Livingston: NO. No one has to buy annual AAA games, but they do, by the millions, which seems to indicate they’re happy with them. Happy gamers are good for gaming, even if I personally think they’re a little crazy for being happy. Not every gamer out there plays dozens of games a year, and not everyone eats, breathes, and lives gaming in general: I have friends who only buy one or two games a year, usually from an annual series. They don’t love them all, but they enjoy them enough to keep coming back. If they’re happy, I’m happy. Why don’t you want my friends to be happy, Tom?

Tom: Because your friends never invite me to any of their parties, Chris. I’m not saying that AAA studios releasing big games for a wide audience is a bad thing—I love the idea of more people playing and having fun with games—but can’t they vary the experiences they are selling a bit? The same gameplay in a different setting year after year is a poor representation of what games can be, and what I know a AAA budget can achieve. The lack of creativity is nothing more than a money grab, because you can save costs by varying gameplay as little as possible. It’s the videogame equivalent of cartoon shows only animating two frames for someone talking. It saves time, but noticeably so.

Chris: I agree, variety is great, and I do wish my friends played more types of games. But you’ve got to start somewhere, and as a jumping-off point, AAA games might not be a bad place to start. At the very least, playing a ho-hum shooter might leave someone wanting a bit more, at which point they’ll really start looking for other titles. After all, most people’s love of cinema doesn’t begin with watching quirky indie films or foreign dramas but probably from watching big, popular, not-so-great movies, like 2009’s Fast and Furious. But it might spark their interest and get them looking for something better, until they eventually find a truly remarkable, deeply-nuanced film, like 2011’s Fast Five.

Besides, if CoD didn’t come out every year, they might not play anything. I figure playing something might lead to someone eventually playing something else, and something better.

Tom: You don’t get Joe Regular into indie films by showing him The Fast and The Furious series, you get him into them by showing him Drive. Look! It’s got famous people, high production values, violence and action, but all of this is presented in a unique and interesting manner. That’s what annual releases could be doing for gaming; they could offer experiences that a mass market is comfortable with in an evocative way. If CoD wasn’t coming out every year, people would still be playing whatever Activision was making instead, because they have the marketing budget and the reach to get their games into as many hands as possible. They just aren’t willing to jeapordize that position by doing something “risky” to make something actually good. Like Furious 7…or, hold on...

Chris: I definitely wish there was a bit more risk-taking and less formula to these games, but even churned-out annual games can wind up being sort of okay. I haven’t played many Call of Duty games, and the ones I’ve played have been far too linear, follow-the-guy, do-what-the-guy says affairs, but I can’t say I didn’t enjoy at least some parts of them. I stabbed a dude in the neck while running down the side of a building, and shot a terrorist in the face on a space station. That was cool. Stupid, but cool.

Keep up to date with the most important stories and the best deals, as picked by the PC Gamer team.

Besides, just because a developer waits years to release the next game in a series doesn’t necessarily mean it’s been completely rethought. Skyrim, honestly, isn’t all that different from Oblivion at its core, and yet it was still good. Is it maybe that your objections come from the fact that you just personally don’t enjoy these annual games? If a new Hearthstone came out every year, you wouldn’t be a little stoked? If the delay between Half-Life games was only two years instead of infinity years, you wouldn’t be down for that? Maybe enormous gulfs of time between games in a series isn’t so great for gaming, either.

Tom: I suppose you are right (and that feels icky to type.) My problem might not specifically be with annual releases, but more with what those annual releases have turned into. I would be fine with a new Half-Life game came out every year if each one of them held up to the same standard of quality, but my point is that’s impossible. Rigid, publisher mandated timeframes do not breed good games, they breed safe concepts that will be purchased. I guess there isn’t anything inherently wrong with that—unless we keep getting glitchy, broken games on release—but my frustration stems from the fact that the developers doing this are some of the only ones who can afford to make large, envelope pushing experiences. And, for the most part, they aren’t.

They aren’t releasing a new game because they have a great concept for one, even if they sometimes do. They are releasing it because it’s expected of them, by the public and their stockholders. Being stuck in that cycle isn’t good for anyone and it’s degrading how we think about games.

Chris: It is definitely a case of quantity over quality. It’s like British TV versus American TV, in a way. With British TV you only get a couple episodes and sometimes years between seasons, but it’s almost always better. Sometimes, though, it can be nice to have a ton (or tonne) of something even if it’s not quite as well-crafted, for those weekends where you just want some noise and images thrown at you without having to actually think.

Here’s at least one perk. AAA developers employ hundreds of people to make their games. Releasing games on an annual basis means they can afford to keep their employees on staff year-round. I think we all groan when we hear about layoffs hitting developers the moment their game is sold, simply because they can’t justify the overhead because their next project isn’t immediately underway. Or do you prefer when a dev lays off people as soon as their game is released? You hate my friends and you hate jobs.

Tom: I hate a lot of things, not least of which is that you make a pretty good point. Layoffs in the game industry happen far too often.

It might be petty, but I just worry about the long term effect this release cycle will have on the perception of gaming. I don’t want the mass market to stop caring about games because all they know is annual rehashes.

Chris: No, that’s a valid concern, and probably not one I’ve considered until now. It would be great if the world at large didn’t only see big annual AAA titles when they took a peek at gaming, but from the outside that’s pretty much all that can be seen, and that’s probably not good.

How about we bury our differences with a film? There’s a wonderful quirky French indie film you should see. It’s called La Fast et La Furious.

Tom: Sorry, I've gotta go see Fury Road tonight.

Chris: I think I'll wait for Fury Road 2. It should be out next year.